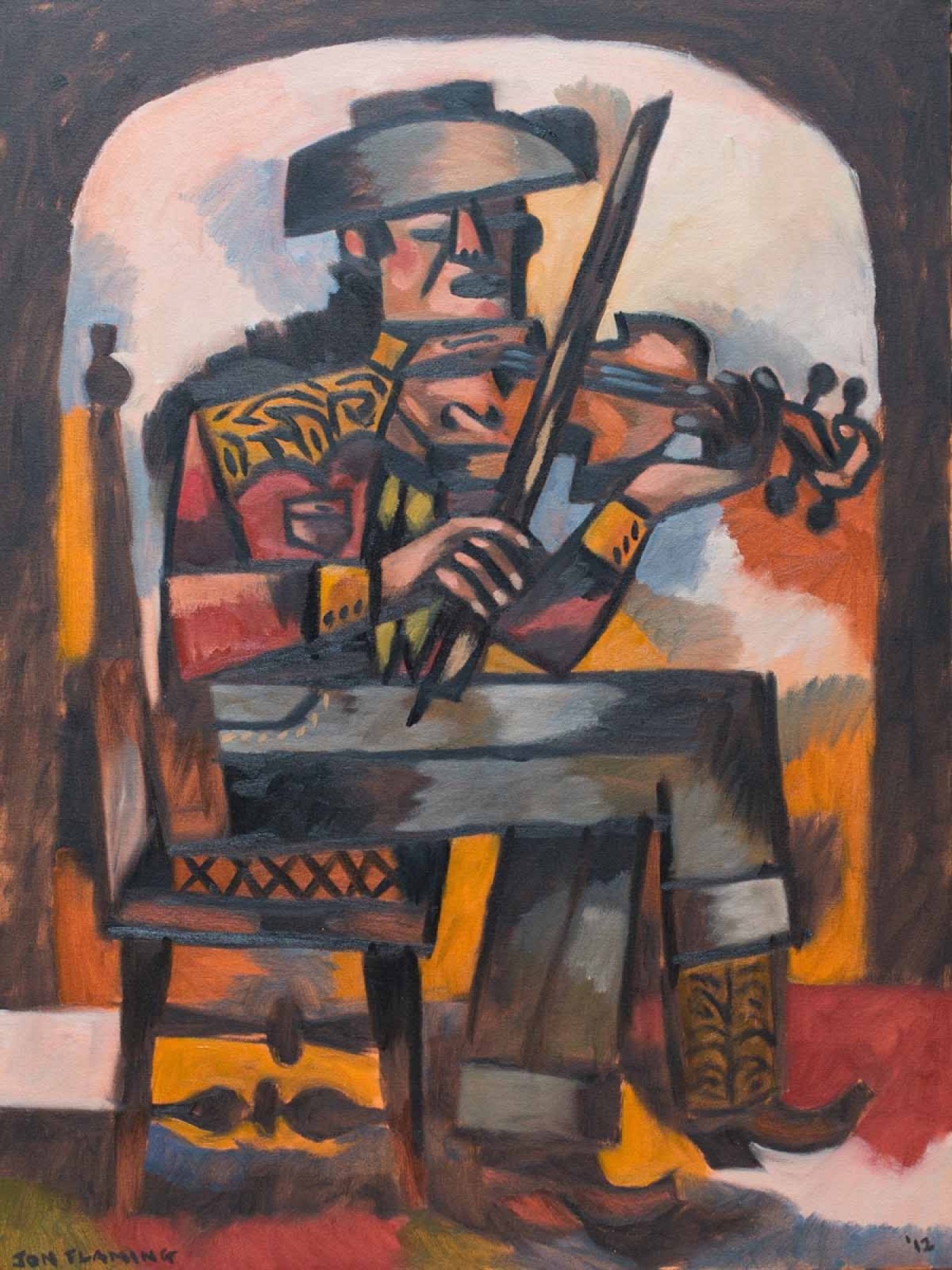

Painting by Jon Flaming

Occurrence at Deep Ellum

By Christopher C. King

The amount of blood pooled up on the Deep Ellum street that evening in March 1931 shocked even those city folk who labored with pig stickers and hooks at the Dallas stockyards. A drunk man bleeds faster, more voluminously, than a sober one, and the heat radiating from the earth that Saturday would have hurried along the lifeblood—an unfortunate confluence of factors. This lethal calculation was not offset by the absence of an exit wound opposite the powder burn on Prince Albert Hunt’s waist jacket.

After having blended with the dust and gravel at the corner of North Harwood and Bryan Street, the satellite of splotches surrounding the pool of blood would have taken on the hue and aspect of bow rosin broken into crude bits, blood-doubles scattered around the scene. Next to the nearly lifeless body would have been his fiddle case gutted and skewing its innards: a now out-of-tune violin, a broken horsehair bow, and a piece of amber rosin, the things Hunt had with him when he played dance tunes on the radio and in Confederate Hall earlier that day. Cedar chips and sawdust would have been cast on the murder spot to soak up the gore. Later someone would have scooped it all up with wads of newspaper.

In that day’s issue, Saturday, March 21, the front page of the Dallas Morning News smugly announced PARTY OF CELEBRITIES STARTLED WHEN DREISER SLAPS SINCLAIR LEWIS and, cautiously, SEEKING ONE WHO KNOWS SOMETHING ABOUT AL CAPONE. A few pages in, under “Movies & Shows,” the reader would have found the salacious lobby card for the most recent Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer talkie showing at the Melba theater: Trader Horn: Primitive Hate Changed To Primitive Love. In Prince Albert Hunt’s case, the opposite conversion of emotions determined his fate and colored the perceptions of those in that town who were called upon to judge a licentious triangle of mortal undoing: temptress, cuckold, and dead musician.

“Prince” Albert Hunt, born Archibald Hunt, was delivered unto the world on December 20, 1896, in Terrell, Texas, the youngest of four children. His mother was a full-blooded Cherokee from Alabama, his father a full-blooded Irishman, and the fiddle music their son played was an amalgamation of the lilting bow figures of the Celts and the untamed war whoops of the Indians. The raspy forcefulness of Hunt’s violin tone reflected the coarse huskiness of his singing, making it easy to imagine his music as the soundtrack to barroom knifings and shoot-’em-ups in dance halls throughout the Deep Ellum neighborhood of Dallas. The drunken swagger of his voice seems to infect the rhythm in his 1928 and 1929 recordings for OKeh records in San Antonio and Dallas. On “Blues in a Bottle,” the guitar accompaniment stalls, elongates the beat, and then spreads the measure so Hunt can drawl out the verse, in effect both capturing and modifying, or marring, time:

That’s my baby,

That’s my baby,

Couldn’t jus’ stand to see me cry pretty mama,

That’s my baby,

Couldn’t jus’ stand to see me cry,

Says ole black daddy, I can’t stand to see you die.

Hunt learned to fiddle by stealing his father’s violin and sneaking away to play in graveyards late at night, cousins and bottles of whiskey in tow. His recorded music is perfectly consistent with this autodidactic approach: teach oneself while drunk in the cemetery such that one must be wasted and wading in death in order to play. One could scarcely anticipate something bad resulting from this methodology.

Prince Albert recorded only nine sides (one remains unissued and is presumably lost), about a decade after he was discharged from serving in the Army during the Great War. Most are vexingly rare—I only have one: “Wake Up Jacob,” with the flip side being “Waltz of Roses,” in “E” condition—and they are fiercely sought after due to their forceful, bluesy nature. Though his recorded repertoire contained the usual suspects—the medicine show tune “Traveling Man,” a Jimmie Rodgers–influenced “Waltz of Roses,” the breakdowns “Wake Up Jacob”and “Houston Slide,” and the show stopper “Blues in a Bottle”—none of his performances were slavishly imitated by others. Even so, Harry Smith thought enough of Hunt to include “Wake Up Jacob” in his seminal Anthology of American Folk Music (Social Music, Dances No. 1, Band 30). Rich Nevins issued “Blues in a Bottle” in his masterful series Times Ain’t Like They Used to Be, Volume 1, and Marshall Wyatt included “Traveling Man”in his Good for What Ails You: Music of the Medicine Shows, 1926-1937. Hunt’s best pieces, in their best sound, are anthologized in Texas Fiddle Music, Vol. 1, on County Records. Although Hunt didn’t alter the course of vernacular folk music, and his influence on Western swing is minimal, he did leave a testament etched in the shellac grooves of his few recordings to an idiosyncratic sound that reflected the mongrel eccentricities of his time and place. Hunt played exactly what the people of Deep Ellum wanted: uninhibited fiddle dance pieces and an occasional waltz.

Hunt’s oldest son, Prince Albert Hunt Jr., recalled that his dad told others that he was “drunk as a hoot owl” when he made his 78-rpm records and that “he drank quite a bit when he was around those dance halls, things, honkytonks . . . I think he kind of drank with the crowd.” Vices get lonely without other vices, so the elder Prince Albert added womanizing and incidental violence to the lineup. Synthesizing these nefarious attributes, Prince Albert became a spiritual brother to two other musicians of the time: Charlie Patton and Charlie Poole. In what could be regarded as one of the universal parables of pre-war music, all three of these musicians are said to have gotten drunk with some other man’s woman, become agitated with her, and then proceeded to smash a guitar over said woman’s head (or, in Poole’s case, a banjo over a policeman’s) such that the instrument was worn as a necktie.

Like Patton and Poole and dozens of other pre-war vernacular musicians, in Hunt’s case this predictable combination of carnal indulgences led to an equally clichéd and deadly conclusion. He would often pick up his violin, leaving his wife and four children just about any time he liked, to go play in the oil fields near Houston or back in his hometown of Terrell. In March of 1931, Hunt had been tomcatting around with Mrs. Hattie Douglas, who was seeking a divorce from W. M. Douglas (sometimes printed as “Douglass”), a bona fide three-time loser. On the night of March 21, Hunt brought Hattie to the dance at Confederate Hall despite W.M.’s direct warning to Hattie to “leave Hunt alone” until after she got a divorce. Of course W.M. showed up that evening as well. At the request of Prince Albert and Hattie, Douglas was searched by a policeman named Paul Barron, who found W.M. unarmed. Barron would be collecting a gun soon enough.

At 11:45 p.m., after Hunt had been playing for probably a little more than two and a half hours, he and Hattie stepped out of the crowded dance hall onto North Harwood. It was there, according to the newspaper reports, that W.M. confronted Hunt. It was an intimate meeting.

W.M. thrust his .25-caliber semi-automatic straight up under Hunt’s lower left ribcage and fired. The bullet from the .25 (which is a horribly underpowered cartridge; it gives the slightest recoil followed by a little whimper between shots) entered Hunt’s anterior sinister abdominal region, traversing diagonally through both lungs until it deflected to the sinister lung lobe and then up again, nestling near the lower dexter ventricle, by his heart. Within this fleshy pinball game everything went tilt at 11:58 p.m. when Hunt was pronounced DOA at the Dallas hospital. This was a love letter straight to the heart.

It was announced on the front page of the Sunday edition of the Dallas Morning News that W. M. Douglas had been arrested after he turned over the handgun to Officer Barron, and he was formally charged with murder on Monday. “He broke up my home,” Douglas declared. “He took my wife clear away from me. He had her at the dance with him and I followed them downstairs where the shooting took place.” As Hunt was a noted radio entertainer and phonograph recording artist, news of the killing appeared on the front page of several Texas papers. Anyone could see that Douglas would be found guilty and likely serve a long stint of hard labor. Opportunity, motive, witnesses, confession, weapon, deceased musician: the options for Douglas’s future movements, vertically and horizontally, seemed dismal, and one is struck by the delusional tenor of his statements to the press. An article on the front page of the March 24 edition of the Corsicana Light reads, “He expressed confidence that he would be exonerated by the grand jury when it heard the facts.” Perhaps it was a fact that Hunt had broken up his home, but that was certainly not a rationale for fatally perforating the viscera of a wanton fiddler.

Yet tucked deep inside the April 4 issue of the Dallas Morning News, tagged to a brief notice of COMMUNIST ACTIVITY CONDEMNED IN REPORT MADE BY GRAND JURY, was a short accounting of “no bills,” complaints and charges that were dropped by the grand jury. Among the “no bills,” tersely worded, was an exoneration of W. M. Douglas. Andrew Patton, the assistant district attorney, released Douglas due to lack of evidence.

Through the lens of our modern sensibilities—our notions of justice, jurisprudence, and knowledge—an acquittal due to a lack of evidence is incongruous if not absurd. This was my line of reasoning as I arm-wrestled this issue with my pal Otto Konrad, a Richmond lawyer and lover of old-time music. He said, “Times were different and a community’s standard for judgment was local. A grand jury would follow the lead of the D.A.” Even so, I couldn’t get past Douglas’s confidence in his looming freedom based on the fact that Hunt “had broken up his home.”

When I was ten my paternal grandfather took me to the local barbershop in Hot Springs, Virginia, the town where I was born and from which I have barely escaped. Sitting on an oak board that spanned the expanse of the two arms of the barber’s swivel chair, I participated in that unchanging ritual of masculine definition: the native good ole boy haircut. Across from me, above a window opening out onto the main street, was a large framed black-and-white photo of two men, bows cocked and suspended over their fiddles, standing on a puncheon that was the center of the image. One bearded man looked wistfully at the camera while the other’s stern frozen gaze at the horizon and to the left of the focal point of the lens suggested that the narrative eye could be missing the whole story. At the time my soft young mind was filled with images from the movies in my dad’s 16-mm collection—Kelly’s Heroes, The Big Store, Occurrence At Owl Creek Bridge, The Great Train Robbery—so I could judge by the garments in the photo that it must have been taken in the earlier part of the twentieth century. To the right of the platform where the fiddlers stood, almost completely marginalized in the image, was a man suspended by the neck from a gallows, a dark sackcloth over his head, stiff. At the time I wondered about the relationship between the musicians on the stage and the dead man on stage left. Now I wonder if this man had broken up a home.

We rarely hear from the temptresses, all the Eves in these stories of offed musicians, the womenfolk who are almost exclusively the fatal snare responsible for the musicians’ unfortunate undoing. Were they attracted to the man or to what the man did or even to the power that the man had over their hips and those of the surrounding dancers? In an earlier, simpler era were these musicians—guitarists at juke joints, piano players in barrelhouses, fiddlers and accordionists at house parties—the conjurors of attraction, the agents of seduction, or were they themselves duped by women wanting a way out or just wanting a flash of attention from their husbands? Perhaps the music makers themselves were drunk with their own power over the dancers. Maybe there is too much blame to be equitably parceled out and these are the unalterable wages of sin. Regardless, we never hear from Hattie whether she felt any remorse or responsibility for Hunt’s death.

Aside from the newspapers of the day and the sparse legal paperwork that has survived, there is also a short documentary, Memories of Prince Albert Hunt, made by Ken Harrison, a Dallas filmmaker, in 1974. Often what goes unmentioned, the noticeable absences and the curious voids, is as important as what you see and hear in any narrative. Harrison interviews many of Hunt’s relations, including his son and his sisters and several townfolk who vividly recall Hunt’s musicianship and lifestyle. What we don’t hear at all is anything approaching judgment on Hunt’s killer. His death is characterized as a mechanism in nature, not a punishment, but a corrective. If a wolf stalks your sheep then the wolf must be eliminated. If a musician runs off with your woman then the musician must be eliminated. You can blame neither a wolf nor a musician for his behavior—as it is part of their nature—but when they are eliminated, stasis is restored, and all is harmonious. Except when it is not.

We will never know what was said in hushed angry tones between W.M. and Hattie Douglas when they gave their statements to assistant district attorney Andrew Patton. The subsequent grand jury was closed and any notes that were taken have not survived. Prior to the grand jury, however, Hattie’s statements appeared in the Corsicana Light:

He [Douglas] came to the dance hall Saturday night, he asked to dance with me saying “You had better get up and dance with me, and enjoy yourself. This is going to be your last dance.” She accused Douglas of first trying to shoot her when she and Douglas came down stairs. “I hit him with my fist and knocked him up against the wall,” she said. “Then I ran and shortly I heard a shot and saw Mr. Hunt lying on the sidewalk.”

This triangle involved three characters, all of whom skirted the fringes of acceptable society at the time. Though Hunt was a womanizer and notorious booze hound, W.M. and Hattie also seemed to live an itinerant existence, particularly after W.M. lost his city fireman’s job, a position that would not have been very accessible to a person who was not well-connected or established in the more respectable echelons of Dallas society. That a man like W.M. could threaten to kill his wife, then proceed to gun down a man like Hunt, accompanied with a full confession, weapon, and witnesses—and then be exonerated within two weeks of the murder for “lack of evidence” was unsettling, as if the narrative eye were missing the whole story.

Early on in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity, Barton Keyes, a claims manager played by Edward G. Robinson (a man I resemble more, year after year, as I inch closer to death), articulates his justified suspicion of a bogus insurance claim in classic noir language: “Every year hundreds of claims come to this desk. Some of them are phonies. And I know which ones. How do I know? Because my little man tells me.” My little man was kicking me in the chest as I reviewed the reportage of Hunt’s death. Late in July of this year my lawyerly musical compatriot Otto called my office and, upon being patched through at the switchboard, simply stated, “You were right.”

“Right about what?” I asked. “But, before you answer, I am glad that I am right and was confident that I was right before we even started this conversation. I like to be right.”

My little man was right but later on my little man was less right.

Otto explained that there was enough evidence to suspect that strings would have had to be pulled to fully exonerate W.M. and that likely there was someone on W.M.’s bond, someone responsible for the machinations that set him free. Unfortunately, this was as far as my little man could go. Someone of considerable respect, power, and influence had to have been involved, perhaps someone like W.M. “Bud” Douglas (or Douglass) of neighboring Arlington, Texas. Bud was city marshal of Arlington in 1894 and again in 1900, later becoming police chief in 1925. Bud and his wife lived most of their lives in Arlington, twenty miles from Deep Ellum, and had no children of their own. When Bud passed away in 1939, at the age of seventy-one, his obituary stated: “During his active life he took an especial interest in young people, boys and girls just starting out in life and if he could help them in securing positions he always gave of his time and influence.” To my mind, it would take someone like Bud to help W.M. acquire a city fireman’s position, as well as to avoid prison for a crime of passion.

Shortly after W. M. Douglas was released from custody, he and Hattie beat a trail to Shreveport, Louisiana. Divorce soon followed. By 1937 he returned to the safety of Dallas and remarried, employed in various sandwich shops on Grand Avenue. Curiously, Hattie moved to Arlington, quite close to Bud’s home, and in 1940 was working as a part-time housekeeper for a family named Douglas. I do not know when death pulled the sheets over Hattie and W.M.

Prince Albert’s cousin, Gracie Hunt Rush, said that Hunt “might of made something out of himself if he hadn’t of died . . . or got killed.” Harrison’s documentary keenly avoids sentimentality by steering the narrative from one relative or informant to another, refusing to rest for more than a few seconds on any one observation or utterance. One outcome of this approach is that the whole story is punctuated with unexpected, profound sadness. In the last scene, a man identified only as a “junkyard man”—but who very well may have been related to Hunt, so close is the resemblance—says of Prince Albert: “I’ve heard them talk about him a lot, but I don’t seem to remember him. I don’t remember too much of my young life. Just very little of it, it just comes and goes.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.