Walking the Tornado Line

By Justin Nobel

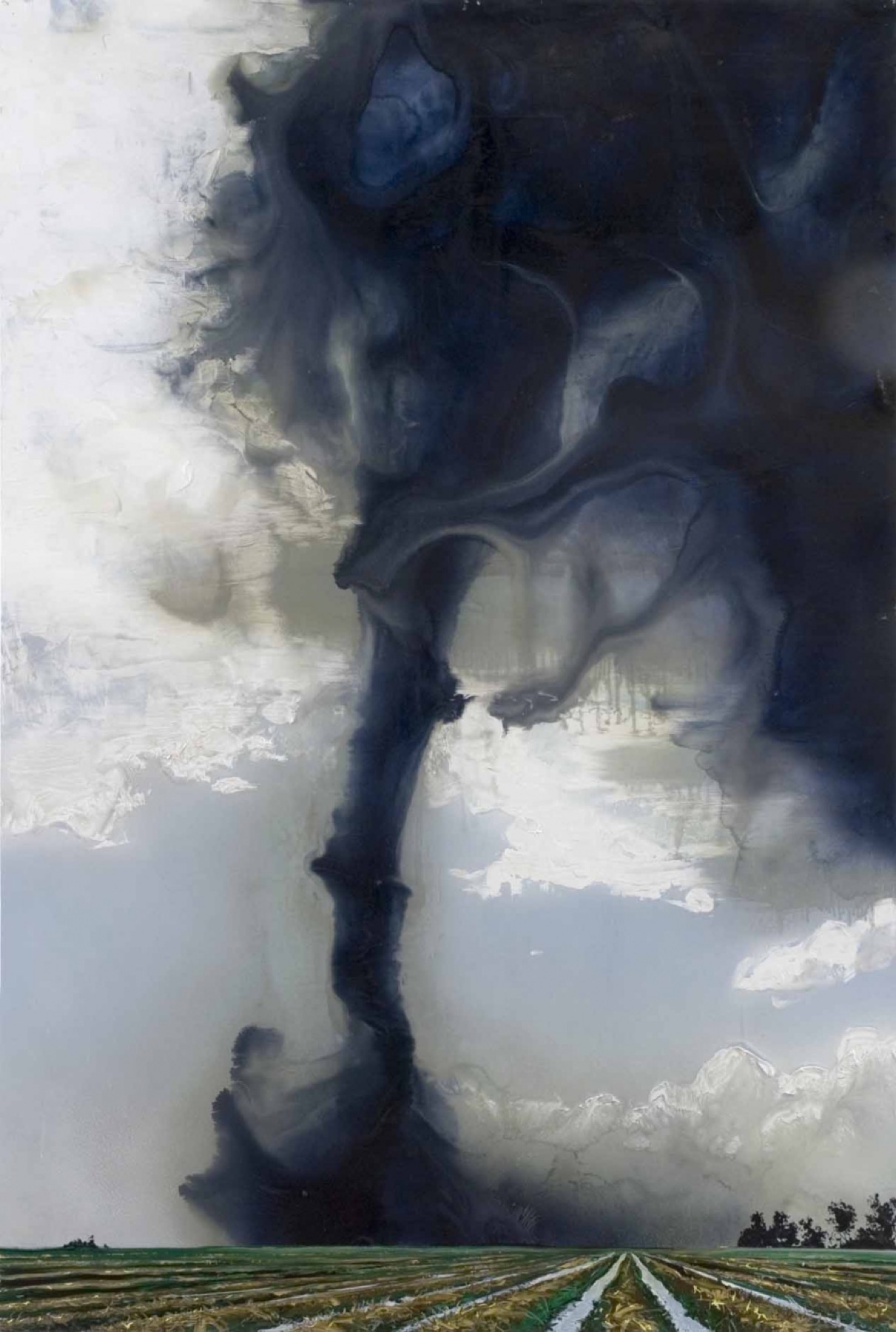

"Blue Tornado" (2007), a painting by Alexis Rockman

“We must attempt to imagine a world where animate and inanimate are indistinguishable, and assume all things possess spirit and power. The tornado, in our newly altered mind-set, cannot be conceived of as a weather phenomenon, but rather, must be seen as a living, breathing animal—a being.”

—Michael Marchand, Mankayia and the Kiowa Indians: Survival, Myth and the Tornado

“A rainbow before me all at once fills me with the greatest confidence. What a sign it is, over and in front of him who walks. Everyone should Walk.”

—Werner Herzog, Of Walking in Ice

On the fourth night of my journey I camp in woods owned by a Baptist deacon named Sammy Swinney. It was here in the rolling hills of northern Alabama where the April 27, 2011, tornado roared through at sixty-five miles per hour, a black cloud the width of twenty-five city blocks with winds stronger than any hurricane. And it was here in the sleepy farming community of Oak Grove that the tornado morphed into something truly unfathomable, and did things few people knew tornadoes could do: ate large brick homes straight through to the foundation, spawned side tornadoes that flanked the main like evil henchmen, climbed a mountain and rattled down a steep valley on the other side, turned an entire forest to spindles, and carried away cars and cows and people, too.

In the morning, Sammy motors over in an old tractor trailed by two dogs, a black lab and a brown mutt, tussling with one another and grinning in the golden light.

“I am going to go disc up this soil,” he says. “Getting ready to plant me some corn and some watermelon and some cantaloupe. I should be back in about thirty minutes and I’ll drive you down to see Wayne Alexander.”

Wayne is an old man with a ZZ Top beard who lives in a trailer with seven stray dogs. Before the tornado he raised chickens in long tin-roofed houses for Pilgrim’s Pride and when the thing hit he was in one with his son, Keith, collecting eggs. They dashed to his truck and Wayne floorboarded it for the storm cellar at the end of the street. “I seen it in the rearview mirror, like a giant lawn mower mowing grass, only it is trees,” Wayne tells me, seated on a couch in his trailer, messy with clothes and books and, lying beside the remote control, a revolver. His wife died of cancer in 2007 and now he lives alone with the dogs. Presently Taco Ball, a Chihuahua, Tinker Bell, a black lab, and Sweetie and Penny, a pair of spotted beagles, are at his feet noisily chomping kibbles.

“It was the weirdest looking thing you ever saw,” says Wayne. “Had a hole right in the middle and the sun was shining through. About that time I heard the trees go pop, and three big old pines fell on us.”

The trees pinned his truck to the ground, and although he was in a coma for more than a week and broke all his ribs, his collarbone, and two vertebrae in his neck, and collapsed a lung, they probably saved his and his son’s lives, otherwise the vehicle would have been whirled away like everything else that Wayne owned: his old Corvette, his old Buick, his new Dodge truck, his 1987 Ramcharger (similar to the one Chuck Norris drove in Lone Wolf McQuade), two motor homes, two tractors, and all six of his chicken houses. “The tornado took everything,” sighs Wayne. But he didn’t have it as bad as some in Oak Grove.

Milton Crochet is the last person on earth you’d expect to be sucked up by a tornado and live to tell the tale. He is a short, pudgy, energetic, bespectacled man in a red “Milton’s Golf Cart Repair” t-shirt, and motions me to sit on a step stool and unload my packs. The walls of his shop are lined with solenoids, engine parts, and brake shoes. His desk is cluttered by more ordinary items: pens, tape spools, a McDonald’s soda cup.

“Well?” Milton asks somewhat aggressively from behind the desk. “What do you want to know?”

Right after the storm a TV news crew was supposed to film his story but canceled when they realized he lived so deep in the sticks. Since then Milton has been dubious of newsmen, and he is doubly suspicious of my ratty packs. But when I tell him I am journeying the length of the April 27th tornado he brightens up—a journey is something Milton understands, and he leans forward in his chair and relates his incredible story:

There were tornadoes spinning everywhere that day and the electricity kept going on and off. My wife, Charlene, was a big skeptic. “It’s not gonna hit,” she said nonchalantly. I went in the house to do something and it just didn’t look right with the weather outside. I walked out to the front yard and it was black, and that’s when I heard something coming through the woods. Thunks and thuds, like “kadink kadink kadink.” I realized it was the tornado, knocking down trees. No thunder, no lightning, I didn’t see none of that. It was just black and it made a thumping sound and I could see cattle in the air and trees with roots and green leaves still on—we’re talking mammoth, mammoth trees—and sections of mobile homes and big sections of houses blown and ripped apart, and a horse trailer, and sheets of metal. You couldn’t help but be mesmerized for a few moments and just look at it, like being in a trance. Am I seeing what I am seeing? This is not real. But this was real.

A call comes in on Milton’s shop phone but he ignores it. His cell phone starts ringing but he ignores that, too, and continues, lowering his voice to almost a whisper:

The black parted and I could see the core, and it was brown, and it was moving left to right, so wide it looked like it was turning in slow motion. When I saw it, I saw death. If you laid your eyes upon this there was death all around. It was like watching someone point a gun at you and pull the trigger, and watching the bullet come at you real slow. You know, chances are it is going to go in your head, and you have to accept it. That’s when I realized we were doomed.

I yelled at Charlene, “Get Rusty in the house, get the kids, it’s a tornado!” Rusty was my twenty-one-year-old son. I had a seven-year-old girl, Georgia, and a ten-year-old boy, Skyler. There was no basement and there was no storm shelter, there was nowhere for us to go to. I got everyone in a little hallway between the kitchen, the living room, and the bathroom, because it had the most walls. Charlene lay flat on the ground with her legs spread in a V and the two kids in between, and her Chihuahua, Pepper. Me and Rusty covered everyone with our bodies, trying to make a shell. We didn’t even have time to put a mattress over us. As it got closer I could feel the pressure, and I could look through the front door and see debris being sucked up. Once it got up on us it got so brown I couldn’t see nothing. As we were all huddled down my wife looked up at me with a funny look on her face and said, “How bad is it?”

“It is going to be catastrophic,” I told her. “Chances are we’re all going to perish.”

Then the metal roof blew off. The house itself literally picked up eight feet in the air, and it twisted to the left, and at that point Charlene yelled, “Oh my god!” and that was the last thing my wife said. The house exploded like a bomb, and we became one with the tornado.

Tornadoes occur over much of the world—northern Europe, Russia, Bangladesh—but like vampires in Transylvania or the Orcs of Mordor, the middle part of North America is where they thrive. About 75 percent of the planet’s tornadoes strike the United States, some 1,250 a year. There are two primary geographic features to thank for this: the Gulf of Mexico and the Rocky Mountains. As low-pressure systems move east out of the Rockies, cold dry air barreling down across the Great Plains meets warm moist air streaming north from the Gulf. The meeting of these air masses, moving at different speeds and also different heights in the atmosphere, creates wind shear, meaning the air is set spinning. When thunderstorms develop in this region of spinning air they too can spin, creating beautiful, terrifying storms called supercells. And it is often somewhere within the supercell, in ways still not entirely understood by meteorologists, that the horizontally spinning tube of air is drawn vertically down to the ground in the form of a tornado.

Recently, a Temple University physicist named Rongjia Tao proposed a series of gigantic walls be built across the heartland to block tornadoes. The meteorologists laughed at him. But if the tornado has no forseeable end, it also has no beginning. None of the meteorologists I spoke with had any idea when the first tornado on earth occurred. Perhaps it was during the Jurassic, in the infant days of the Gulf of Mexico, when dinosaurs walked the land. Perhaps it was earlier.

These days, we understand Tornado Alley to be a stripe across Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas, but in the Deep South tornadoes can actually be stronger, last for longer, and kill more people. A 2007 paper in the journal Weather and Forecasting examined tornadoes from 1880-2005, taking state area into account, and listed all fifty states by number of killer tornadoes and number of tornado deaths. At the top of both lists were Mississippi, Arkansas, and Alabama.

Researchers have suggested several reasons why this is so. The South has higher population densities than the Great Plains, more poverty and mobile homes, and higher humidity levels, due to proximity to the Gulf of Mexico. Moister air means Southern tornadoes are more likely to occur at night, in the winter, and be cloaked in low clouds and wrapped in rain, making them difficult to see. Further obstructing Southern tornadoes are forests, which block the horizon and are filled with trees, a ready quiver of tall spiky things that can be snapped off and sent airborne.

Research published in 1972 in the journal Science examined tornado preparedness among people in Alabama and Illinois and found another factor: God. When compared to Northerners, Southerners were more likely to distrust government-issued tornado warnings, discount technology-based weather forecasts, and believe their security lies not in their own actions, but in the Lord. “Each Alabamian is on his own,” reads the paper, “and faces the whirlwind alone with his God.”

The Super Dixie Tornado Outbreak of April 2011, the second-largest tornado outbreak in U.S. history, spawned more than three hundred tornadoes, including one on April 27 that was shown eating its way across downtown Tuscaloosa on national television. It looks like a monster out of a child’s nightmare. An even more powerful tornado struck just eighty miles to the north that day, but it ran through a very rural region and received practically no news coverage. That was Milton’s tornado, and the destruction it wrought was beyond devastating; it was absurd. The tornado unleashed winds of more than 200-miles-per-hour, obliterated the towns of Hackleburg and Phil Campbell, leveled a Wrangler Jeans plant, barely missed one of the nation’s largest nuclear power plants, and skirted the grounds of a state prison. The storm killed seventy-two people in Alabama, making it not just the state’s deadliest tornado, but at the time the single deadliest tornado in the United States since the Udall, Kansas, twister of 1955.

Born a few miles from the Mississippi border, outside the town of Detroit, Alabama; died in eastern Tennessee, over a spiny ridgeline in the shadow of the Appalachians: a life 132 miles long.

My own life’s path began in the North, with a strong interest in meteorology. My family’s kitchen countertop served as a tiny weather bureau, and I used Rice Krispies to track nor’easters up the coast on a United States placemat. When they hit I would put on my winter hat, snow pants, and boots, and slip into the night, to spend the storm wandering the woods with my dog, Mickey. As childhood ended and adulthood loomed before me, weather became an attractive portal of uncertainty, and I attempted several heady journeys into the elements. On Mount Rogers, the highest peak in Virginia, which I tried to scale alone in a blizzard, I got lost in a labyrinth of rhododendron so thick I had to abandon my packs. I eventually found a stream by listening for a gurgle under the waist-deep snow and slithered down the frozen peak following a single light in the distance that appeared through the thicket like a god. In the Mojave, a friend and I tried to cross a dry lake bed in the middle of summer, and I almost lost the friend. Later, wanting to see the ocean and its storms, I traveled as a reporter to the remote Pacific islands of Yap. While sleeping on the deck of a cargo ship anchored off tiny Satawal Island an alarm sounded: we were drifting. A typhoon had sprung up in the night and I rushed to the rail to watch the monster black waves. Soaring shakily above them was a flock of seabirds, frozen in flight. They crashed onto the deck and the islanders dragged them inside to cook. From adventures like this I learned two lessons:

wind.

for the

1. All creatures are food

2. A

storm be-

comes the

world.

A few years back, I fled the North, because it was too expensive and too familiar and I met a lady in a fiery dress who also wanted to run; her name was Miss Karret. We moved to New Orleans in a van filled with cats and dogs and I plied my trade. Occasionally, I left the lady and animals at home and drove around the place on reporting missions of my own design, sitting in small towns, hearing people’s stories, entering their worlds. I pored over maps and devoured books and listened to the landscape, and by and by, I learned about the April 27th tornado. Last spring, feeling it had been some time since I’d gone through the weather portal, I unearthed my packs and plastic bag of medicines, kissed Miss Karret goodbye opposite City Hall because the road was blocked for a marathon, and sprinted down Loyola Avenue to the Greyhound station.

New Orleans to Tupelo, fourteen hours on a near-empty coach, much of it bending across the Magnolia State, the deadliest tornado state, cows and sunshine, McComb and Durant, billboards of lawyers and Jesus. GOING IN THE WRONG DIRECTION? I SPECIALIZE IN U TURNS. Grenada, where the Greyhound stops for gas and in the shade of a tree with magenta flowers I eat leftovers packed in an old snorkel mask case we’ve been using as Tupperware. Sunset, night bus, night trees, night noises. At midnight I arrive in Elvis’s birth city, where on April 5, 1936, a tornado killed at least 216 people, the fourth deadliest in U.S. history. Many more surely died but at the time black fatalities went uncounted.

At a highway-side motel I find the night clerk splashing water on his face before a minuscule sink, wearing black slacks and suspenders. “Nature has a twist,” he tells me, “always something unexpected.” In the morning, which comes soon, he is dozing on a sofa with the Weather Channel blaring; tornadoes are in the extended forecast. I stuff toast in my pocket and hop into a banged-up white cab that drives me fifty-five miles to the Alabama border, fog hovering over the farmland, mist rising off the ponds, sun beaming in my eyes, and high up in the blue sky, a creamy half-moon, like a lemon meringue pie with a bite taken out. At 8 a.m. the cab drops me in tiny Detroit. It is Easter Sunday and hot. My packs are cozy, one on my back, one on my chest, making me compact, like a tortoise crawling over the land.

Outside of town dogs rush me. First a black collie, then a pit bull, then two massive gray pits, lumpy and furious. I am prepared and sprinkle bacon-flavored treats in my wake. Soon more pits, six or seven, rushing down a dirt driveway, a shirtless man hollering after. Then, a Chevy Malibu pulls up beside me and the window is lowered.

“Excuse me for asking this, but you aren’t a serial killer, are you?”

“No,” I reply.

A kid with curly orange hair lets me in and says he can show me where the tornado began. “I was going to college out in Florence,” he tells me, as we curve along a country road, “but my job cut me down to four hours.” No longer able to pay tuition, he had to drop out. Now the kid lives in a field of wildflowers with his grandmother. His great-grandfather lost his first wife to a tornado that struck in the 1920s, impaled by a tree limb, and during the Super Outbreak of ’74, the largest tornado outbreak in U.S. history, his father helped unpeel the victims from tree trunks.

“Here,” says the kid, idling the Chevy, and I try to digest the geography. Slice of farmland banked by tall dark trees and a lonely cabin where lives a woman who apparently witnessed the tornado drop out of the sky, scared to death. From there it scampered off into the forest, still a weakling, headed northeast, and toward the small city of Hamilton.

The Enhanced Fujita scale rates tornadoes from EF0 to EF5 according to the destruction they inflict on structures and trees. On April 27, just north of Hamilton, the tornado mysteriously blossomed from an EF1 to an EF4 in a matter of miles. No one knows for sure what caused this tornado, or any for that matter, to strengthen so quickly, but Stephen Strader, a meteorologist at Northern Illinois University, believes the storms that moved through northern Alabama earlier that morning left a warm moist region of air in their wake, known as a thermal boundary. When the tornado hit that boundary it exploded in strength and became enveloped in thick clouds. This was the South’s old nemesis, humidity, and the mostly invisible tornado ripped northeast through the woods along Highway 43 and ran smack into the town of Hackleburg, destroying 75 percent of the structures, killing eighteen people, and smashing the Wrangler Jeans factory to pieces. Blue jeans were siphoned into the air and spread across the land.

In the predawn I plant myself at Hackleburg’s main hang, a Shell station called the Panther Mart, watching old-timers drink coffee and kids on their way to school drink juice and construction workers on their way to work drink Monster energy drinks and the sun creep up between the fuel pumps. Just after 8:00, Marion County commissioner Don Barnwell arrives.

Meteorologists had been warning residents for days about the likelihood of a tremendous tornado outbreak. The first sirens rang at around 3:30 A.M., says Don, then again at 6 A.M. Neither of these storms produced tornadoes, so when the siren rang for the big one, at 3 P.M., many folks figured it was another false alarm, until they saw the fierce black wall closing in on the town.

“I just didn’t think it was that bad,” says Don, elbows spread on the table, fingers by his lips, as if he’s telling me a great secret. “I thought, we’ll have trees to cut, and I came up to town and there was no town, and we went to the Piggly Wiggly and there was no Piggly Wiggly. Then we began hunting bodies. I found a black-headed boy laying in the parking lot, shaking, and I tried to flag an ambulance but they all just kept passing.”

Don has a handlebar mustache and watery eyes. He looks like a NASCAR driver, but a sad one, one who has just lost a big race, or maybe all of his races. Turning my business card over in his hands, he tells the onlooking customers, “This guy’s the real deal,” and our table quickly becomes a confessional.

Big Jerimey Gallaway, owner of Smokin J’s BBQ, who sits beside me chugging whole milk: “I told everyone to get in the bathroom. There were five kids—we got more kids than that but we only had five at the house. I was the last one in and shut the door and we all just squatted on the floor. It ripped the roof off the house and took one shed and blew it over the house and took the other shed and put it on the house, but we were alright.” Except, somehow, the tornado ripped a cap out of Jerimey’s mouth.

Joel Britnell, a rail-thin man with a bruised red drinker’s nose and white puff of lightning-struck hair: “I was in the master bedroom lying on the carpet. I’d been trying to get in the closet, took the carpet right out from under me, towed me over. Thought that was the end of my time, couldn’t get up. Crushed my right ankle, cracked my pelvis, broke my left knee, and crushed three ribs. I watched the house leave, picked the whole thing up, furniture and all, blown it up like a balloon. Last time I saw it was over by Doug’s, in the air.” Joel lifts up his jeans and shows me his leg, which is lined with scars and splotched pink, white, and blue, like a worn-out flag.

Don wants me to talk to a man named Johnny Ray. He and his wife were blown into separate fields by the tornado and both went into comas and both survived. But Johnny, who in the quick glimpse I get resembles a lizard with a hat on, says he’s busy.

Touring the destroyed town in Don’s Heavy Duty pickup, I see farm houses blown to bits, mobile homes wiped off the map—no one really escaped. His second cousin was killed, “slung up every which way.” She had taken her kid to her mother’s place then gone home to get something for the kid and was sucked up by the tornado before she could make it back. Many stories like this: the decision you made in the fifteen seconds before the tornado struck meant your life. At the shell of a home, top gone, only a basement, I peer in and see mason jars and a coffee pot and stairs leading up to nothing; the couple was found in a field. Don points out the plot of land where the debris was burnt and buried, the site of the wrecked grammar school and the new one going back up, new churches, the new Wrangler Jeans plant, rebuilt with state money he helped obtain. Beyond the plant, the tornado chopped northeast through the woods toward Phil Campbell. Trees without tops, trees snapped in two, trees grated like cheese, trees that can no longer be called trees because they have no branches and no leaves but aren’t exactly dead, all of it strung with shiny tin bits, pieces of the Wrangler plant, and weaving through the shattered forest is a river, strange and vulnerable without its plush, leafy coat. At the town cemetery, neat well-tended graves with colorful bouquets, Don breaks down. “My son is buried out there,” he says. “He went to Iraq, came back and had a car wreck.”

It takes all day but I find Johnny Ray, in a sub-development at the top of town, standing in an open-air garage fixing something. He hobbles over, grumpy, dismayed, wearing a yellow Nautica tank top and sky blue Panama City Beach trucker’s cap. “I don’t remember nothing,” he says immediately, but it turns out he does remember some things:

Me and my wife left at ten after three to go to the farm and check on some calves. By the time we got there the tornado was on us. I put her in the bathtub. When it hit it blew me one way one hundred yards and her the other way one hundred yards, and it blew that whole damn blue jeans plant right over the top of us, trucks and sheet metal and everything. When I woke up and looked around everything was gone, and my wife was gone, too. They hauled us up to where the church was at and took her to one hospital and me to another.

As we speak, that same wife, in an outfit much more dapper than Johnny’s, is showing a handsome young landscaper what needs to be done around the house. Johnny was sixty-one when the storm hit and in good shape, thanks to a life spent outside in cattle and construction. The tornado crumpled his body, and like a baby he had to learn to walk again. Three years on, he’s worried he’ll never fully recover. “Just a hard kick in the ass,” says Johnny, seated in the cab of his truck, kind enough to drive me back down the hill to the Panther Mart. “That’s all it is, a hard kick in the ass.”

Heading east out of Hackleburg in the fading light on County Road 172 toward a campground near Bear Creek I get two rides. One from a cop in a spiffy black cruiser who says he hid from the tornado with the former mayor in the old jail cell—smart move; the rest of the police station was destroyed—and the second with a hunched man named Nathan selling $20 steaks out of a cooler in the back of his truck. Beside him is a blind poodle he saved from the flames after his trailer caught fire, short-circuited because of storm-related power outages. This has actually happened twice, says Nathan, once right after the tornado and once again this past week. “Enough people have helped me out,” he reflects, making room for me beside his poodle. “Figured I can help some people out.”

The campground is a happy place with kids riding around on bicycles and RVs set about a pretty lake. I string my hammock next to the misfits, a friendly couple in rags that look to have once been biker wear living in a home constructed almost entirely of blue tarps. Although the forest floor is crawling with aggressive centipedes, it’s a lovely spot and I cook a pasta dinner on my camp stove and fall asleep under a cricket roar. In the middle of the night there is rain, first drizzle then downpour, and I find myself wishing I was under the tarpaulin mansion with the post-apocalyptic biker couple. When I rise, cold and wet in the yellow dawn, I know I am getting closer.

In Phil Campbell I learn that the tornado ripped the hide off cows, blew away a medical clinic—destroying the town’s medical records, still kept on paper—as well as a gun store and two pharmacies. So the storm, which was already raining down cows and blue jeans and twisted sheets of metal, was now raining guns and Adderall. Criminals and pill junkies streamed into town and the FBI and ATF—Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives—came to look for the guns (they found about 100, out of 300). The National Guard stood watch over the rubbled pharmacies, and church groups from across the nation arrived to cook food and rebuild. The Rescue Squad building, which houses EMT ambulances, was transformed into a morgue. The community center, even though it was badly damaged, became a place where people could get showers and clothes and meals provided by the church groups. Also in the Rescue Squad was a makeshift pharmacy, heavily guarded, and a small store with sundries like toothpaste.

“You don’t think you’ve lost everything but you have,” says Phil Campbell’s chief of police, Merrell Potter, who is shiny and tiny with smooth edges. “I remember one woman didn’t even have clean underwear to put on.” In his spare time, Chief Potter, who has a twin brother on the force named Terrell, preaches at a country church.

We spin through town in the rain in his beat-up white cruiser. As we cross the train tracks, Chief tells me, “I don’t mean this in a negative way but every town has a place that is considered rundown and this area over here was that. We had people move in and start manufacturing drugs. They got blown away, and a lot of that riff-raff didn’t come back, and I don’t miss them.”

He stares for a while into the rain, and I sense the preacher in him making his way out. “We got purged,” says the chief, brightening up. “The tornado can be a rebirth.”

That evening, Ava McCurley, Bear Creek’s sparkly town clerk, grants me a cot in the town’s tornado shelter, located in the basement of the community center. There are no windows, nothing but white walls and white chairs and tables, and when I turn on the eerie fluorescent lights it feels like a conference room in heaven. During the tornado, which missed Bear Creek by just a few miles, some two hundred people crammed into the shelter. “I was there from about one o’clock up until midnight,” Ava tells me. “We started getting casualty figures from Hackleburg, then the injured from Phil Campbell. Two ladies came in who must have been dehydrated, their homes had been destroyed and each of them had a little dog. They were the walking dead, like zombies, bless their hearts.”

Ava gives me a towel and three-pack of Coast soap. I wash up, and in the fading light of day, she returns to pick me up for church, dressed in an elegant blue dress with a necklace of polished stones. With us is grandson Carson, a contemplative young man in a mustard-colored blazer who sits in back twirling an ancient Scottish sword with an ornate handle called a dirk. Ava drives us so far through rolling hills in the crepuscular light that we cross the path of another April 27th tornado, arriving at a Baptist church backed up against a cliff in a lush glen. Inside Carson sings in a large enthusiastic choir, followed by a group from Louisiana in green suits with guitars. Then, a traveling preacher in a white collared shirt stands on a table and belts out pronouncements like a free-style rapper:

Everywhere we look, someone is in trouble,

they are hurt, they are broken,

they are bruised

Folks are looking for something.

Amen. Amen.

I don’t need anything else,

God saved my soul . . .

These old revivals,

we need to have ’em,

I know it’s out of style,

But it ain’t

out of style

with

God.

Six Phil Campbell churches were destroyed by the tornado, including Mountain View Baptist, a large church on the northeast side of town. “I was watching it from the storm shelter,” says Pastor Sammy Taylor. “It was roaring and whistling like a train, and it was a mile wide. When the tornado came over the church that steeple just shot up like a rocket.” Pastor Taylor tours me through the shimmery new sanctuary in his New Balances, a soft square-faced man with a military buzzcut gone white. The church was built in the exact same spot as the old one by the volunteer church construction group Builders for Christ.

There are many bells and whistles: a baptismal font that more resembles a Jacuzzi, an audiovisual room, a “crying room” for new parents, a puppet theater for young teens, an indoor basketball court for older ones, and bookshelves and cabinets throughout crafted by a master woodworker from Virginia. “See how much God has given us,” says a beaming Pastor Taylor. In his office he shows me something truly special, a Bible that was buried under debris and pierced through by a wooden stake to exactly Psalm 74: Turn your footsteps toward the perpetual ruins; The enemy has damaged everything within the sanctuary.

How would you characterize the tornado, I ask Pastor Taylor, considering the tragic loss of life but that your congregation also ended up with a fabulous new church? He has been waiting for this question.

“You have two spiritual forces,” begins the pastor, “good and evil, and they are at constant war with each other. It has always been that way. Let’s say I’m God, and here comes the tornado, and I believe it was sent by the Devil. God could have turned it away, but it passes his all-scrutinizing eyes. When God sees all that good that can come of it, he permits it to happen, knowing the passage will also create destruction. That’s when faith comes in, because you don’t know when the good is going to come about, and that’s cool stuff!”

Before leaving, Pastor Taylor gives me a pin, which I accept, and a pen, which I accept, and a t-shirt, which I don’t accept, then he blesses me: This is not by accident that Justin has stopped here, this is by providence, and I pray for him and his safety on his walk, and I pray for his salvation, and I pray that he may communicate with You, and find You on his walk. The pastor drives me a few miles northeast along the tornado’s path to Trapptown, where he drops me off at a country store. He tries to buy me a juice or soda or just put some money in my hand, but I say no, and then he is gone and I am on my way. Four miles down the road I come to Oak Grove.

Milton takes a sip from his McDonald’s soda cup and continues:

At this time you’d assume everyone’s knocked out. Uh-uh, I was awake. It went from silence to a raging force of power you cannot comprehend, it was just too powerful. Things are hitting your body, jerking your body, your body is being trampled. The tornado don’t just suck up, it consumes itself as it goes. There were pockets in it that had nothing but space, and I could see through the tornado, I could see the backside. I said, “Lord, if someone has to die just take me, save my kids.” I was comfortably relaxed. I was not afraid to die. I had lived a good life. I treated people right. I knew my Lord Jesus Christ. I was waiting for that hit to take me out, but that hit never came.

I remember hitting the ground still conscious. At this point you’re numb, your brain has not comprehended the pain yet because it was so fast. You are probably in shock. Hundreds of tiny projectiles have been shot into you. I looked down, it looked like I was a human body with pins all stuck through. Blood is running everywhere. There was a two-by-four that had grazed my stomach and chin. My pants were all shredded up, my shirt was gone, my shoes were gone, and for some reason my left sock was down around the ankle.

Out of the corner of my eye I see something fall. It is my son, falling off a debris pile. He fell and he started running for the woods, and I yelled his name, and he came my way. When he got to me I told him to turn around; he looked fine, just little scratches. Then I told him to check me. My son had to look at my backside to see if something wasn’t sticking out, because I was hurting bad.

“There’s nothing there,” he said. “But you’re cut up bad and there’s meat hanging out.”

“I can’t believe you’re alive,” I told him. “We gotta find everyone else.”

“Well daddy,” he said. “Georgia is right behind you.”

We dug her out. Her head was swollen real big and she was pinned in a lot of metal and her left knee was swollen and she was bleeding bad out of her right ankle, something had chopped it. She was real sleepy and losing consciousness, we had to keep her awake. At this point you’re catching up with the pain, you’re starting to hurt everywhere, but you’re still driving to find your family.

We found Rusty buried under a bunch of trees. He was in bad shape, kind of like that show The Passion, where they rip the Lord Jesus with a cat o’ nines. The back of his head was cut four inches long and four inches wide and I could see his skull, and some clear stuff oozing out.

“Now we gotta find Momma,” I told the kids.

Skyler started yelling and there was no response. I sensed that she was dead but kept looking for her, I wanted to see her. Then something said, “Beware, you’ll have to live with what you see.” It was subconscious, as if you’re walking in woods and you find a rattlesnake curled up. Not making noise, just curled up.

I heard another voice, Charlene’s voice, and she said, “Take care of our babies,” and I said, “Okay.”

The evening air is muggy and the sky electric. A line of squalls is building to the southwest. I am seated on a comfortable sofa with Justin Morgan, a burly college English teacher, and his wife, Brittney, a middle school counselor, in their spacious Oak Grove home. Justin was part of the group that found Charlene’s body.

“When I saw her I knew she was dead,” he says. “She was a big tall woman, and she had not a stitch of clothes on. It was raining horizontally, and I remember how the rain bounced off her. It was just the complete absence of life. She looked like a prop from a movie. She was white, all ashen, and she was almost cut in half.”

Another tornado was on the way and the sky was darkening. Milton and his kids were put in an SUV to be taken to the hospital. Before the vehicle could leave he hollered to Justin, asking if he had found Charlene.

“I just couldn’t tell him,” Justin says to me. “Not then, I couldn’t let him see her like that.”

Turns out Justin and I have a lot in common. He is a writer, too, and while he loves teaching he has had other aspirations. “I wanted to be Hemingway,” he tells me excitedly. But he stayed in Alabama and fell in love with a woman and proposed to her in the forest behind the home we are presently seated in. “December 12, 2006,” says Justin. “I took a rake and lined a path with field stones. At the end I built a pedestal and put my ring box there, then I paved the path with petals. We were gonna build a log cabin in that spot.”

On the patio, in the blue light of the slowly approaching storms, Justin shows me what has become of the forest. About half a million dollars’ worth of white oak, red oak, poplar, beech, hickory, and sycamore trees were torn down by the tornado. The trees were eighty to one hundred feet tall. “Straight-line winds pushed them over, and the tornado twisted and braided them and broke the tops off,” says Justin. “The tornado had so much strength it opened up the trees’ sinews.”

With the forest gone it is hotter in summer and colder in winter, and without a natural barrier winds are stronger. Justin developed allergies, and he has stopped hunting deer because it just doesn’t seem right to shoot them in the leafless space of the wrecked forest. The cabin in the spot where he proposed to his wife was never built.

“You can smell it,” says Justin, after the strongest, closest lightning bolt of the night. “You can smell the moisture, and you can smell the rain.”

And he is right, as we speak

huge fat raindrops,

a million miles apart,

like water pails hurled from the

Sky,

and a hot wind

blowing up from the dead trees

naked trunks bending backwards,

gutters rattling and

in the distance

horizontal lightning

gives off orange

shadows.

And to the south and west

a growing

glowing

yellow

welt

in the

Sky.

“I shoot everything through the Jesus Prism,” says Justin, as the rain steadies. “I have a biblical worldview. I believe we live in a fallen, sin-filled world, and that brings on things like this tornado.”

Just northeast of Oak Grove I scamper up a hillside thick with new shoots and scratchy bushes and prickly vines, ripping my flesh in the thicket, busting out through tall grass to the crest where I peer down into the valley. The tornado swabbed the whole thing clean of trees, and winds rushing into its core flattened the woods on the steep slopes above, leaving an entire valley and the hillsides on either side branch-less and nude. To the north the land flattens, and a broad wide valley stretches all the way across Lawrence County to the Tennessee River.

“It came off that mountain like a big ole octopus,” says Gene Mitchell, sheriff of Lawrence County, a grandfatherly man with coiffed white hair and aviator sunglasses, a pistol on his hip. He watched the tornado from his squad car, parked on an overpass in the middle of State Route 24, trying to decide where the thing was headed so he could begin sending rescue vehicles behind it.

“It had these tentacles reaching out,” continues Mitchell, “these smaller side tornadoes, and they would be going back to the main.” He describes clouds racing in from the opposite horizon toward the storm, truly racing, and theorizes that the tornado’s descent down the steep mountain created an energizing suction. The strangest thing was the color. “When it crossed an open field with nothing on it but dirt the tornado would go red, like a sunset,” says the sheriff. “And when it crossed a wheat field it would go a creamy green.”

Sheriff Mitchell isn’t about to let me trek alone across his domain. Besides, he is running for re-election and has a minivan full of lawn placards and window stickers he’s aiming to distribute. He drives me across the county on bumpy local roads, passing fields of lettuce and fields of flowers and a handful of long white tubular bunkers: new community tornado shelters. “The damage here was just horrendous,” says Mitchell, in tiny Langtown. Up at Dot’s Soulfood, in Hillsboro, a big open cafeteria with checkered tablecloths, he treats me to a hearty lunch: candied yams, home-fried potatoes, Brussels sprouts, pinto beans, hush puppies, catfish, pecan pie. As the sheriff goes for seconds on pie, I speak to a wiry old man in suspenders named Laurence Davis Jr. who farms watermelon and cantaloupe down the road. He operated what was arguably the county’s best barbecue joint, until the tornado leveled it. “Knocked me through the floor,” says Davis. “Had to climb out a hole.”

The sheriff drops me, along with some campaign literature, at Mallard Creek Fish Camp, located on a wooded cove on Wheeler Lake. I spend two days drinking bootleg beer and moonshine, dozing on the lake’s buggy shores, and chatting late into the night around gasoline-initiated campfires with the owner, a friendly man named Jimmy Collins who wears a jean jacket with cut-off sleeves and has a wolfish beard and flowing white hair. He works the four-to-midnight shift at a factory in Decatur that makes tire fabric. Rather than sleep strung between the pines in my hammock, Jimmy insists I bunk in an old touring bus parked on the lake. At night I get up to pee out the alcohol under the stars and look across the glassy water to the pearly lights of the Browns Ferry nuclear plant, which splits uranium atoms to make power for two million homes. The tornado missed it by less than two miles.

It missed Mallard Creek, too, but several residents were elsewhere when the storm hit, and have stories.

David, a stocky man in boots and old jeans, was in his trailer at a campground directly in the storm’s path, on the other side of Wheeler Lake. “I put my shoes on and got to the door and that’s as far as I got.” The tornado flipped his trailer on its side. “I got my gun, jumped out the window, and looked around,” says David. “There was nothing left.” Worried about looters, he climbed back in the window and got his AK-47, then went door-to-door checking for bodies. He found one man impaled by a piece of metal. In another spot the trailer and everything in it had been blown away, except a birthday cake and the table it sat on.

Roy Grinfin, whom everyone at camp calls Peanut, was at work in the Independence Tube plant in Decatur. “The clouds were black, with some pink and purple,” says Peanut. Blue jeans started raining from the sky, some fit to wear (their origins the Wrangler plant in Hackleburg, sixty miles away). “Me and about seven other coworkers took shelter in our safe place, a concrete block bathroom. We could hear the tornado ripping the plant to pieces. There was so much pressure you could see it expanding the blocks, like they were breathing. In ten seconds it was over. We opened the door and it was like looking at a barren plot.”

The tornado sucked twenty-inch anchor bolts out of the plant’s four-foot-thick concrete foundation. Railway ties were plucked from their tracks. Steel tubes as long as school buses were swallowed by the storm and shot back out like arrows. “In a matter of minutes,” says Peanut, “people lost everything they worked for.” At dawn, two Mallard men scoot me northeast across Wheeler Lake in a small fishing boat, past blue herons and egrets and the hulking blue building that houses the three nuclear reactors of Browns Ferry. Our destination is a campground on the north side of the lake in Limestone County, less than a mile from where the tornado came ashore. The air is grimy and yellow, like spoiled milk has settled over the Tennessee Valley. At the new campground people are pulling out—a storm is coming. A hot wind blows across the lake, and kids are riding the swim dock as if it were a giant surfboard. The campground host and her son drive by on a golf cart and give me a ham sandwich and a banana. “It’s the hot and cold mix,” she says, pointing out over the darkening lake. “This is just like it was three years ago.”

I walk east on Nuclear Plant Road toward the town of Tanner, over swift-flowing tea-colored creeks and bright green wheat fields, under an army of high-tension wires, with their human stances and owlish heads. Some forty fell in the tornado, crumpling like gigantic walkers in the Battle of Hoth. Drizzle becomes sheets of rain, dry bellowing thunder becomes hot close flashes of lightning. A man named Ron Smith, sitting on his porch in his socks, black lab Charlie at his side, invites me to duck in. In the midst of the torrent his old lady pulls up and spills out of the car, a bit unhinged, loaded down with plastic shopping bags. “People are rushing about down there,” she says, exasperated. “The shelves were practically empty.” Tornadoes are on the way.

At a hotel in Athens, Alabama, I peel off wet clothes and eat peanut butter out of the jar while watching tornadoes erupt across Iowa and Nebraska. Outside, lashing rain, roaring thunder. “You need to be under the lowest levels of your home, away from windows, and please act fast,” warns the Weather Channel. As night falls, tornadoes break out over Missouri and Arkansas. One rips through Central Arkansas, leveling the town of Mayflower.

When I wake at dawn, tornado watches are already being posted for northern Mississippi. In the lobby old ladies are eating waffles and outside the sky is shiny. I take a walk but don’t know where I’m going. And the wind is picking up, sheet metal is already somehow in the air. Outside low brick apartments a group of women stands around in colorful pajamas smoking cigarettes. “Where will you go?” I ask. Bathtub.

Back in front of the hotel TV. A tornado moving through Grenada, tennis-ball-sized hail. Grenada, where in the shade of the tree with magenta flowers I had eaten lunch. Tornado warning in Tupelo, where the Greyhound dropped me off and I spent the night at the highway-side motel. “Folks, this is scary,” says the weather forecaster, “it appears a quarter-mile-wide multi-vortex tornado with tremendous rotation is headed right for Tupelo. An unbelievable storm moving right into Tupelo, this is coming into Tupelo right now!”

Suddenly, my phone starts buzzing and I jump off the bed. It’s Limestone County sheriff Mike Blakely.

“We’re mobilizing,” he tells me. “Getting folks with chainsaws, making sure officers have emergency equipment, spray paint, talking to our spotters, loading ATVs onto trailers, briefing our people to make sure we’re all on the same sheet of music. What I gotta do is run home and get a change of clothes. According to the National Weather Service everything they’re afraid of happening is happening.”

I ask Samantha, the receptionist, to show me the hotel’s shelter, which turns out to be a dark slot between two plasterboard walls, pink insulation spilling out, wires hanging down: a deathtrap. I shove my essentials into one pack and hit the streets. Blakely had mentioned a firehouse nearby, and that is where I go.

A bright new structure in a field surrounded by sub-development homes. Inside, antsy firefighters drink coffee out of a great scorched urn and watch the bright red trapezoidal warnings break out across the TV screen. Tornado on the ground in Red Bay, headed northeast at fifty miles an hour, another near Russellville. Tornado on the ground in Hackleburg. People in Phil Campbell told to go to safety. Langtown is being hit like a drum. The tornadoes are following me, racing my way like winged monkeys in The Wizard of Oz, a rip-roaring belt of gremlins or goblins, eating through the TV screen like Ringu, eating existence itself like Langoliers. Only, as Milton said, this is real. “If you live anywhere near here,” says the TV weatherman, pointing to exactly where we are, “I would be going to my shelter.”

But the draw of the storm is too great. Instead I stand outside with a group of firefighters and search the skies for the tornado. We are like sailors’ wives on our widows’ walks, scanning for ship masts. Scalloped clouds race over the white picket fences, long deep eerie belches of thunder sounding indefinably from the southwest. Then, a yellow light glowing over the trees, it has arrived.

“Tornado warning in Limestone County,” crackles the radio. Sirens go off. Immediately afterward two radio calls: a pregnant woman’s water breaks, and a man is stabbed. A cop speeds into the parking lot with his girlfriend and her frightened mother. On the radio, the town is being torn to pieces: Funnel cloud over the college. Wall cloud has wrapped around the west side of town. Be advised: Storm should be crossing I-65. Just lost power at the board of education. Tornado Warning extended.

The tornado is moving across the horizon a few miles to the north, like a cone or wedge—the left side of the wedge is gray-black, and on the right side it is green. Exploding blue lights are transformer lines falling. An apartment complex caves in. Fires flare. The trucks roar away into the storm. Who’s in charge? Wind-whipped horizontal rain. One lightning bolt goes through a cloud like a spear and emerges out the other side. The cop’s girlfriend is recording on her phone. A crippling bolt strikes in the field right in front of us and the sky goes purple in the vacuum left behind. Quick green clouds, I write over and over in my notebook, sketching tiny twisters. Trees perform a strange genuflection. An egret stuck in the wind. Every dangled knot of dark cloud is trying to spin. Now I understand, there is never just one tornado, there are infinite tornadoes: the air wants to become lethal. A vortex opening right above me. I see under the flank and into the core, I see something like pieces of glass shifting in water, gray swirling slag bits racing together, bits glomming together to build larger bits, like a robot assembling itself in the sky. I see the whirling, the spiral-shaped eddies, the galaxy clusters. This is what the formation of a star must look like, or the universe itself. Lightning squatting on the ground, pulsing energy right into the land, electricity streaming from sky to earth, a transfer of power is occurring, and high above, spidery splinters crisscross the air. Then, a cold wind.

“I’ll be honest with you, I’m from the North and I never experienced anything like that day,” says Keith Polson the next morning at Browns Ferry nuclear plant, where he is a vice president. We are standing on a covered walkway near the cooling towers. “Starting at eight or nine A.M. we had numerous times where it would darken up and you would see the clouds rolling,” Keith continues, as a fox slinks by a drainage ditch near the parking lot. “At four or four-thirty I went to my office thinking everything is safe. It seemed really weird to me because it looked like the birds were flying very high up in the air, and I said, ‘Why are those birds flying up there?’ Then it started raining down shingles and tin and paper. The sky was putrid green and all of a sudden the wind came up, and I ran into the bathroom. There were probably five of us. We could see big pieces of plywood and metal flying by. Later, diaries and books from little kids were found on the roof. Immediately afterward, my boss from Chattanooga called and said, ‘How are the units running?’”

The plant itself was fine. The problem was eight of the nine large transmission lines that carry power out had gone down. This caused what is called a load reject, meaning the plant had nowhere to put its power, which immediately triggered an automatic reactor shutdown. A bank of eight diesel generators came online. Control rods were inserted into the core to absorb neutrons and slow reaction rates, and a series of steps were taken to cool the core with water and shut down the plant. The energy for this, while it was still available, came from the reactors themselves, and later the diesel generators. Even if the generators—housed in two concrete bunkers, one on either side of the plant, behind three feet of steel-reinforced concrete—fail, cooling water can be piped to the core manually, using energy from a room of backup DC batteries. Each individual battery is about the size of a steamer trunk, and there are backup battery banks for these backup battery banks. The reactors themselves are behind a concrete containment structure called a drywell, which is three feet thick and lined with steel, and the lower section of the big blue reactor building is surrounded by three-foot-thick concrete. “For a tornado to penetrate all of that,” says Keith, “is pretty much impossible.”

But the greater danger might lie elsewhere. Uranium fuel spends six years in the core, then is cooled underwater in a spent-fuel pool, then placed in dry storage, which means transferred to ten-foot-wide, two-foot-thick concrete casks and stored on-site in neat rows on a concrete pad, designed for an EF5 tornado to blow right over. Nuclear waste like this was scheduled to be buried under a mountain in the deserts of southern Nevada but the federal government shut off funding several years ago for that project, which means waste is stored on-site at the facilities where it is produced. “My concern with the nuclear storage is not so much with it being picked up and thrown,” says Stephen Strader, the Northern Illinois University meteorologist. “My concern is with debris being thrown into it. If you can imagine something being sandblasted, except this is not sand, this is cars.”

A Liberian cab driver named Jallah drives me to the entrance gate of the Limestone Correctional Facility in a well-battled white Crown Victoria. He wears cool blue shades and a beige collared shirt.

“You ain’t got no firearms, hand grenades, any of that good stuff?” asks a beefy guard.

“No, man,” says Jallah, and steers the Crown Vic up the winding driveway, smirking.

Workers are exiting the prison carrying clear plastic backpacks that display their contents. Inside, prison guards in fatigues strut randomly around what looks like the foyer of an underfinanced elementary school, cracking jokes. I relinquish my packs and pocketknife and cell phone and guards lead me down a narrow hallway with small offices to where Warden Jimmy Patrick is waiting, a short thick man with a tissue box decorated in fishes on his desk. Warden Patrick is in the National Guard, follows college football, and loves his wife and three kids. At one point she calls and he proudly explains into the phone that he can’t talk: “I have a magazine journalist in my office.”

His tornado story is a good one. A morning twister on April 27, 2011, brought torrential rains and seventy-miles-per-hour winds, and downed some trees. At 11:30 A.M., the county let the schools out, and the warden picked up his kids, dropped them at home, then returned to the prison. Around three o’clock the weather started getting ugly again, and just after four he turned on the TV to learn that a tornado was coming across Highway 72, several miles to the south. The warden called his wife and told her to take the kids to the storm shelter.

“The sky over the prison got very dark,” says Warden Patrick, “and you could look up and see paper falling, and then bricks began falling, and the more they fell the darker it got. It looked like a cartoon. All the clouds were running together.” This wasn’t just a massive black cloud, the warden realized, this was the tornado, and it was heading right for the prison. He and a few other workers took refuge in the little hallway outside his office. They feared a direct hit, but just as the tornado was entering the prison’s grounds it veered east. The roof of the armory was damaged, and one of the prison’s beagles was taken by the twister (it was discovered a few miles away with a broken hip), but the main buildings were spared and the staff and inmates were okay.

Worried sick, Warden Patrick ventured out to check on his family—the tornado had shot directly for home, where his wife and children were huddled. When he turned left out of the prison’s main gate cows that were supposed to be in their pastures were lying dead in the road. The prison’s K-9 officer drove him in a four-wheel-drive vehicle the back way across the pastures, maneuvering around fallen trees until the countryside became impassable. The warden continued on foot to his neighborhood. One house was still standing, and it was his. He went to the shelter and opened the door and his wife and kids came rushing out.

Outside, a dry raspy thunderbolt cleaves the sky in two. “Tornado watch has been issued for Limestone County,” an administrator calls out to me. I was planning to camp north of Huntsville, but with more tornadoes on the way sleeping beneath trees in a hammock now seems foolish.

“What about the inmates?” I ask the warden before leaving. “What do they do in a tornado?”

They take their mattresses to the common areas and lean them against the concrete walls and lie up against the mattresses and pray.

Raindrops tumble from the sky as Jallah drives us past a quarry, a gigantic mountain robbed of its rocks, its innards eaten. We cross over a swollen brown creek and slice northeast across the top of the state. Jallah came from Liberia, the country of his birth, straight to Alabama. “It was a shock,” he says. He chose the Athens/Huntsville area because he had a Liberian friend there. He married a woman from California and started a cab company but recently has run into trouble. The city of Huntsville refuses to let him operate two cab companies. Two is necessary because each company can only have one cab at the airport pickup line, a significant source of revenue. Other operators have budded off second companies just to get that second airport spot, but these operators, “the good ole boys,” as Jallah calls them, all seem to know the right people on the right regulatory boards. Jallah doesn’t. He is presently in court against the city.

“They see too much color here,” says Jallah. “They don’t see the real thing. The nation I come from, we don’t know shit about white man, black man, brown man. We were never colonized. I never knew anything about white man’s behavior.”

We pass a truck broken down on the side of the road. The sky is boiling gray. The storm is coming and we are racing it.

“Humans don’t understand the natural world,” Jallah continues. “I grew up on the coast, I swam in the ocean with nothing on me, and I don’t even care about any of that, because the animals in the sea are more important than us.”

Clouds sailing to earth like small skiffs entering port. Frothy white tubers of water gushing out of caves. The forest is wet and alive.

“Will humans survive?” I ask Jallah.

“I can’t say, but one thing I know, I don’t care how strong man is, how much man creates, the supernatural is beyond man’s capability. We were created by some supreme being that had more power than us, and I don’t—I don’t know how to describe it, but it is much more powerful than you could ever think.”

Jallah’s words reminded me of something Milton said:

People tell me, “Oh, this was a big EF5,” and I’m laughing. What’s big? Compared to the size of the earth, a mile and a half ain’t nothing. Looking down from satellites, in the perspective of the world, it is just so tiny. I was inside it, and from what I seen it has the capability to get as wide as it wants. It can be triple the size. There is almost no limit to how big it can become. This could be an EF1 to the earth, and the earth could be laughing. People tell me, “Milton, that don’t make sense.” And I tell them, “Exactly! What I seen don’t make sense.”

Stout mountains, thick hollers; weaving around in the hills, we slip into Tennessee. Vine-ensnarled silos lofting above fields, waiting for someone to save them. In this area the tornado spit out restaurant receipts, prescription pill bottles, and photographs picked up in Alabama towns one hundred miles away. I am following my sweat-dampened maps, dictating directions to Jallah, trying to decipher the dissolving printouts in the fading light while crouched over in the back of the Crown Vic. The road kinks and we enter the tiny empty town of Huntland. City Hall has bumblebees painted on it; COUNTRY HAMS AND SIDE MEATS reads a sign on a grocer. An empty post office—everything is empty, people are gone, gray clouds gob up in a tangle.

Our road spills out into the countryside. Vistas open, homes are fewer and fewer, and in the distance I see the darkening hills, the beginning of the Appalachians. At a fork, my directions end. To the left the road jogs north, eventually back through town and to a highway which will take us to another highway that will take us to Chattanooga, where there is a Greyhound station and I can catch a bus back to New Orleans and Miss Karret. To the right is a blaze of dirt road that ends near a farmhouse, beneath a boney low gray-green mountain slumped like a sleeping dragon. Straight ahead is a house with a light on and the garage door open. We idle in the driveway, and I wait for somebody to come out but no one comes. Jallah thinks I should get out and knock, but I am not so sure.

“This isn’t the right spot,” I tell him.

I am running out of vibes, I am running off fumes. We are running out of road. Then I notice that there is one last farmhouse before the road disappears beneath the dragon peak. “That’s the spot,” I tell Jallah, and we bounce down the rutted road, the Crown Vic as much out of its element as we are. An old Nissan pickup appears from the farmhouse, trailing a cloud of dust, headed our way.

“Stop him!” I instruct Jallah, and he does. I scoot across the backseat and lower the window just as the sun breaches the cloudbank and spills orange onto the hills and onto the roadway and onto Jallah and me and the kid driving the pickup, who has freckles and a drawl and curls coming out from under a cap, and the sun explodes the curls in fiery light. He is on his way to work and in a hurry. I can hear a fuzzy radio coming from his truck, warning about a supercell capable of producing large hail and tornadoes racing through Harvest, near the prison that we just left. At first the kid thinks we are talking of the tornado that came through last night and begins showing us where that one took down trees, but then he understands.

“You can’t see now but it ran right over this hill,” says the kid, pointing behind him out the window and down the dead-end road toward the low gray-green sleeping dragon. Yes, he says, the tornado ran up the hill, it ran and it ran and it ran and it ran up that hill, and somewhere on the ridgeline it disappeared and was gone.

Interview: Justin Nobel on the reporting of “Walking the Tornado Line”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.