Wouldn't Take Nothing for My Journey Now

By Claudia Perry

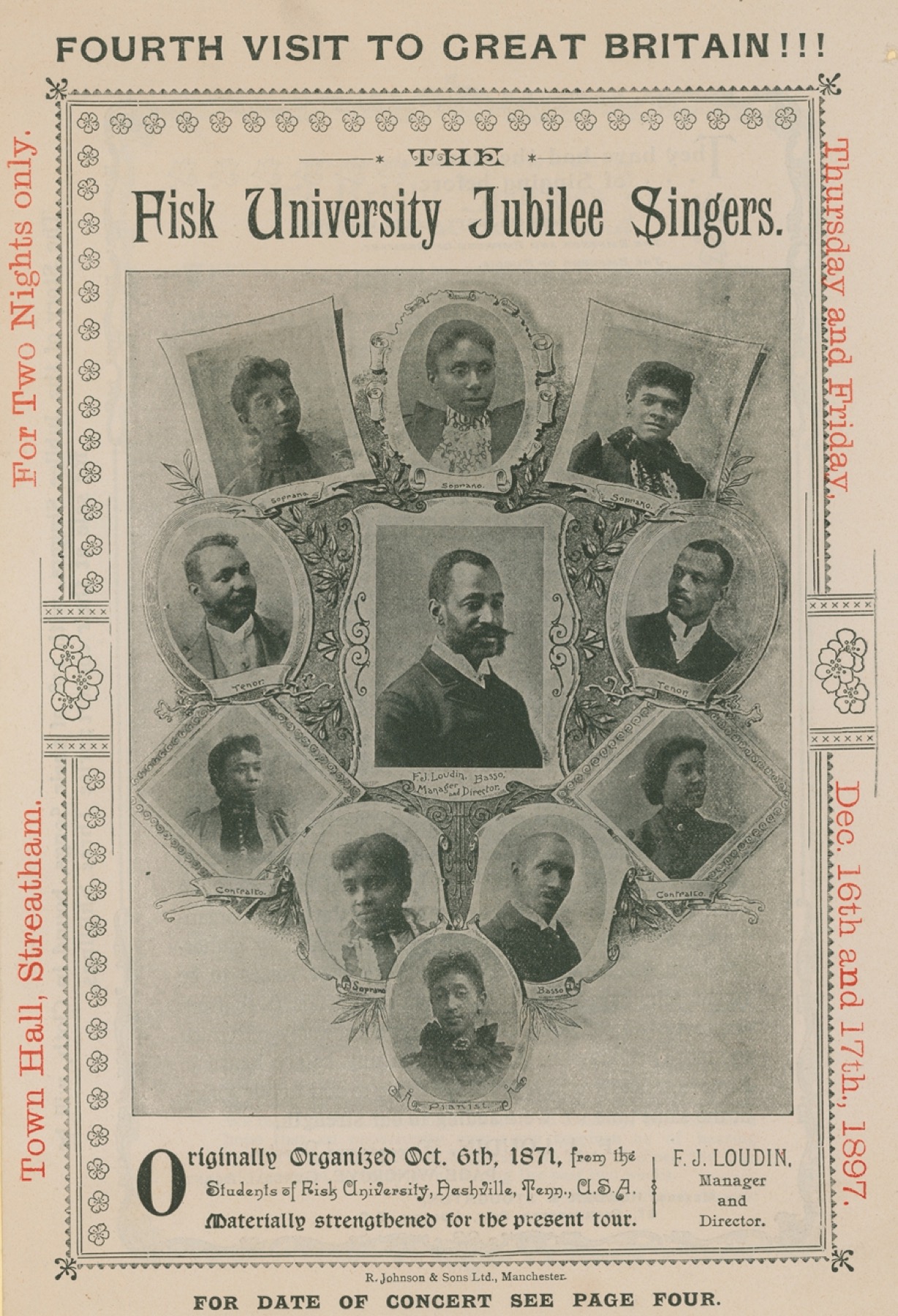

Loudin’s Fisk Jubilee Singers, 1897, courtesy Portage County Historical Society Museum.

I felt a little weary of Jesus as we traveled. Although my voice was womanly, I was still a girl of fourteen years. It was not that my belief wavered, but I grew tired of being in strange surroundings. I did find beauty in the green hills of Scotland and the waters of Holland. The travel on steamships was also exciting. And when we sang, many of my cares melted away.

We sang and we were reminded that we were doing this for Fisk, to erect a grand building to house our campus. Fisk is a college for free colored men and women. The school inherited an old army barracks near the river in Nashville, but that brought the fever to many of the students and teachers, so it was decided we should try to move. I was happy about the news. It was much better to be far away singing than home being sickly.

We sang with Jubilee Hall in mind. We sang of the trials and tribulations of our ancestors. I do not remember much about slavery. We are free men and women. We started by singing some slave songs, but also the songs that people played on their parlor pianos. But those songs were not what people wished us to sing. I tamed my hair and wore nice dresses as did the rest of the women in the group. Over time, we stopped singing everything else we knew how to sing in favor of the slave songs. We sought out former slaves to teach us the songs that were not ours, but were our history. By doing so, we made our talents more pleasing to white audiences. They were shocked that we were not like the minstrels.

We are good Christians and we have benefited from our association with the American Missionary Association. Our director, George White, was part of this group and was against slavery. The missionaries wished for more Negroes to be educated, but some of their number wanted us to return to Africa once we were more learned. I do not feel any connection to Africa as my family has lived here for all of my life.

Before we went to Europe times were very hard, and Mr. White had my family send money so the journey could continue. Part of that hardship extended to finding lodging when we performed. In the North—a place we had dreamed was free of prejudice—we could not always find lodging because of our skin color. I always hoped that Christian charity would extend to us from these innkeepers. Perhaps it was too much to hope for. But we did find kindness from people who opened their homes to us.

Our faith kept us going. We sang “Go Tell It on the Mountain” and “Steal Away.” There were many times when I was slain by the Spirit and its sweetness as our voices blended in harmony that could have only been touched by God himself. Those were the best times. We met royalty and other dignitaries who seemed genuinely interested in our talents, but I would trade all of those meetings for our most spirit-filled performances.

Most of the people we sang for had not yet made a Negro’s acquaintance. So they assumed we were unlettered; simple even. That was not who we were, but it seemed that was who they wanted us to be.

After some time, the people we sang for found delight in our performances, which cheered us. And the campus was growing and moving away from the fever zone. Mr. White and Mr. Cravath, who was leading Fisk as it grew, decided we should go to Europe, because we needed a new audience from which to raise funds for our school. I was tired, and my voice was ragged because we sang so often and with very little rest, but I prayed for strength for this journey. Mr. White looked after us, but our well-being suffered. I do not know if he could really see us as anything but children in need of care. I will never know, but he did lose his health as did many of us. So did his wife, who was Mr. Cravath’s sister. Ella Sheppard, one of the strongest and kindest people in our group, helped Mr. White a great deal and her joyful spirit lifted us up often. She even paid the tuition at Fisk for some of her sisters. She kept a diary which she allowed me to read on occasion.

“It fairly made me tremble to see and know the cause of such a congregation of unconverted souls. No doubt they said to their own hearts that they were going to hear the singing but I earnestly believe it was the Gospel truth their souls really sought. Anyway, thank God, they did hear the Gospel and in a way both by preaching and singing they shall never forget, whether heeded or not.”

Whatever oceans we crossed, audiences were surprised by our appearance. Some were disappointed because we wore no head wraps, loincloths, or what they thought would be African dress. But we were not African; we were Americans of our time and place. I could not understand why they could not see us for whom we were. That we were at least three generations removed from those ancestors did not seem to be a thought they could embrace.

There was not a way to find what people wanted. They wrote that our music was too Negro and laughable. “Often so much they are not inferior to the songs of the civilized world,” a reviewer wrote. “Any more profane and degrading performance it would be difficult to find. Some of the most sacred names and incidents in Scripture were set and sung to Nigger Melodies of a laughable kind,” wrote The Town Crier while we were in England. We found it hard to be of good cheer in the face of such judgments.

Many of the people we sang for seemed fascinated by our skin and hair, though some also complained that we did not look as they expected Negroes to look. My light skin and long hair were often singled out. Someone in London said I looked as though I came from the south of France. “I was disappointed they were not blacks,” one reviewer wrote in Holland. “Two women were as white as I am, although their hair and thick lips revealed their descent.” Jennie Jackson had the darkest skin of all of us and she received the most attention from men who sought her hand in marriage (Mrs. Wells did not permit responses to those inquiries). I continued to pray for Jennie when she became ill and had to stay in Holland before returning home after some time there. I also prayed for Julia Jackson, who was no kin to Jenny. She suffered a stroke in England.

We received peculiar questions, as though we could know every Negro in our country. People asked after people they knew in Chicago, whom of course we did not know. We also were given what may have appeared to be compliments but had a strangeness to them; we were told how well we represented our noble race. We could not think of a proper response to such comments so we remained silent and were thought to be very shy. We were also tired because we would sing several concerts a day. We would perform at several churches. Then Mr. White would have us sing at the biggest hall he could find and charge people to hear us. Some who heard us sing were shocked by our dignity.

I wanted to continue my education so I left the Singers after one year of touring in 1878 (I did return briefly in 1882, but that was a time of turmoil for the group). Though the journeys of the group continued, mine did not.

I will never know for sure how much of what we raised went to building Jubilee Hall. We were paid for our singing, but some complained about how that was handled. I do not know what Mr. Cravath told Mr. White after each sojourn. Whatever their conversations, the result was another journey. I felt some pride in helping the school grow and thrive. Those feelings were mixed with some anger as to how the Singers were treated during the eleven years of singing around the world. We sang of Jesus and the glory of God’s kingdom, and there was beauty and honor in doing that. We made something where nothing had been before, a school where our people could be educated and take their rightful places in the world. I remain proud of that, but also know the struggle behind that triumph. You may take this account to be nothing but a record of our afflictions, but they were inextricably mixed with our joys. As one of our number wrote, “These songs came to us, as it were, fresh from the hand of God, as he gave them to us, in order to give utterance sometimes to our woes, and sometimes to our joys.”