Ruth Asawa at Black Mountain College

How the Japanese-American artist developed her practice in the North Carolina mountains

By Colony Little

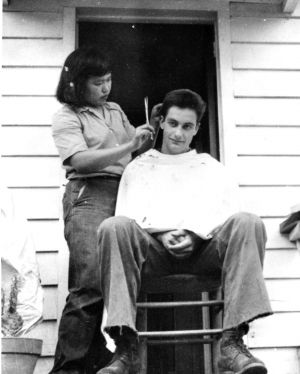

Ruth Asawa and Ora Williams (Carter) at Black Mountain College, 1946. Photograph by Mary Parks Washington and courtesy of Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

This piece originally appeard in Burnaway, an online magazine that celebrates art in the American South and the Caribbean, and is a feature release of the Oxford American x Burnaway co-publishing initiative.

Ruth Asawa, aspiring to become an art teacher, attended the Milwaukee State Teachers College from 1943 to 1946, but the school refused to assign her a student teaching role she needed to graduate, citing lingering anti-Japanese attitudes. As a result, she was forced to drop out. This rejection would send Asawa down an unlikely path of creative exploration that influenced her artistic and academic career.

The origin of this path began at Black Mountain College, a liberal arts school deep in the Blue Ridge Mountains of North Carolina. The institution radically challenged the intellectual and philosophical underpinnings of school governance and teaching practices, prioritizing independence and democratic principles that privileged the process of learning over the formalities of rank and academic designation. Under the tutelage of Josef Albers, Asawa refined her approach to material, process, and pedagogy, famously noting that Albers didn’t teach students how to draw, “he was teaching you how to see.” By examining the contours of line through a disciplined practice of repetition, she mastered the art of meandering with a plan, a process she extended into her personal journey as she encountered detours in her life. Black Mountain catalyzed Asawa’s artistic career—traces of their influence recur in her biomorphic, looped-wire sculptures, origami fountains, and public monuments. Asawa eventually found her way back to teaching art, invoking Black Mountain principles within public schools in San Francisco. Asawa didn’t follow a map or a prescribed path to chart her career, instead she navigated life using Black Mountain as her compass.

Black Mountain College, founded by John Andrew Rice and Theodore Dreier in the 1930s, was located near Asheville on 640 acres of verdant farmland in the Blue Ridge Mountains. At its peak the multi-disciplinary, multi-cultural community of exiles, artists, and performers created a perfect storm of artistic expression in the 1930s-1950s, attracting art and design juggernauts including Buckminster Fuller, Jacob Lawrence, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage. While at Black Mountain, Asawa drew from her rich life experiences, creating a series of successive works that personified her adaptability, resourcefulness, and discipline.

Ruth Asawa was born in Norwalk, California, in 1926 and raised in a family of Japanese truck farmers in a rural, unincorporated community east of Los Angeles. As a child working on the farm, Asawa traced interlocking hourglass shapes into dusty dirt tracks with her foot as she rode on the back of a horse-drawn land leveler. She indulged her artistic proclivities by becoming an avid illustrator with dreams of attending the Chouinard Art Institute, however, amid a climate of anti-immigrant land ownership laws, intensifying anti-Japanese sentiments, and economic disenfranchisement, her educational prospects were completely derailed during the Great Depression and World War II.

Ruth Asawa drawing while incarcerated at Rohwer War Relocation Center, Arkansas, 1943. Photograph courtesy of Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

In the wake of Pearl Harbor in 1942, FBI agents arrested Asawa’s father under the unjust Executive Order 9066 and imprisoned him in New Mexico while Asawa, her mother, and five of her siblings were forced into incarceration in converted horse stalls at the Santa Anita racetrack. At Santa Anita, internees maintained schooling for detained children; Asawa took art and illustration classes with incarcerated Walt Disney animators including Chris Ishii, landscape artist Tom Okamoto, and cartoonist Ben Tanaka. Asawa was later transferred to the Rohwer War Relocation Center just outside of McGehee, Arkansas, where she continued to draw and paint, using the skills she honed in California to become the art editor of her high school yearbook. After graduating she was released from Rohwer to attend Milwaukee State Teachers College, and while there befriended a fellow student named Elaine Schmitt whose older sister Elizabeth attended Black Mountain College. In letters she sent to Elaine, Elizabeth beckoned her sister and friends to attend the progressive, liberal arts school.

Josef and Anni Albers joined the teaching staff at Black Mountain as émigrés from Germany during World War II, eventually encouraging fellow Bauhaus stalwarts fleeing persecution to teach at the school. While most students studied at Black Mountain for a semester or single summer session, Asawa spent three years there, learning through a curriculum rooted in repetition, revision, and refinement, core principles that Josef and Anni Albers adapted from Bauhaus traditions that espoused intuition, collaboration, and experimentation. During the 1946 summer session Asawa took core classes in design and color with Josef Albers. A favorite drawing exercise of his was the Greek meander, a single repeated interlocking line that resembles a key motif, repeating the meander through varying articulations of scale, shape, and shading. In class students presented their work to one another, detailing how they approached a particular assignment; through these critiques, Albers taught students to focus on process over product, instilling discipline in gathering information that they later applied in successive classes. Instead of completing a course and graduating to a higher level of study, Albers encouraged his students to maintain fidelity to the original material by manipulating and interacting with it in new ways.

The school was notoriously cash and resource strapped—students relied on everyday materials to create their work so frugality, upcycling, and resourcefulness were beneficial skills. While arduous work-study requirements—including manual labor—dissuaded many students, Asawa embraced these challenges as opportunities for learning. Asawa was uniquely prepared for her Black Mountain experience. “We used everything that was natural around us . . . I grew up on a farm, and I knew that we always improvised on the farm. So, I felt very much at home because it came out of necessity rather than having everything in front of us.” Through this approach to problem solving, Asawa continued to apply this process of adaptation in her life, using what was around her to create something new.

Asawa’s notes and drawings during her three years of study reveal familiar patterns in color, material, and shape. She frequently drew variations of the meander motif, playing with perception, line, volume, and transparency using ink, collage, and other techniques to experiment with the pattern. Examining her adaptations of the meander, the seeds of her most iconic biomorphic forms take shape; in other modes of experimentation she would translate her two dimensional drawings into three dimensional sculptures through origami; she would then reverse the process by deconstructing her work and drawing new two dimensional shapes. Echoes of the meander would reappear many years later in the carved doors found at the entrance of her Noe Valley home in San Francisco.

Asawa’s travels to Mexico, particularly her trip to Toluca in 1947, offered fertile creative ground for translating the concepts she honed at Black Mountain into three-dimensional, sculptural renderings. While she taught school children in Toluca, Asawa also learned how to make looped-wire egg baskets which would become the foundation for her looped-wire sculptures. When she returned to Black Mountain she toggled between two-dimensional representations of a continuous, looped line and the transparent “form within form” structures she created with wire, remixing this concept for decades. This sustained practice of experimentation marks the genesis of the rules and concepts that defined her metier.

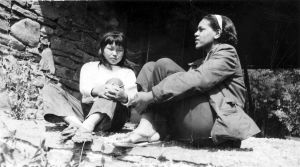

Ruth Asawa and her children in the sunroom of her San Francisco home, California, 1964. Photograph by Ernst Beadle. Artwork © 2025 Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc., Courtesy David Zwirner.

Asawa met her husband, architect Albert Lanier, at Black Mountain and the two relocated to the Bay Area to raise six children. She continued to make her wire sculptures while experimenting with new, unconventional materials like salt dough, also known as baker’s clay, made from a simple recipe of flour, water, and salt. A familiar occurrence, necessity became the mother of invention. “If I didn’t have my own children I would have never explored working in dough . . . because I had six children at home I had to find things to do with them, and it began with making Christmas ornaments. They are very much the inspiration for working in dough.”

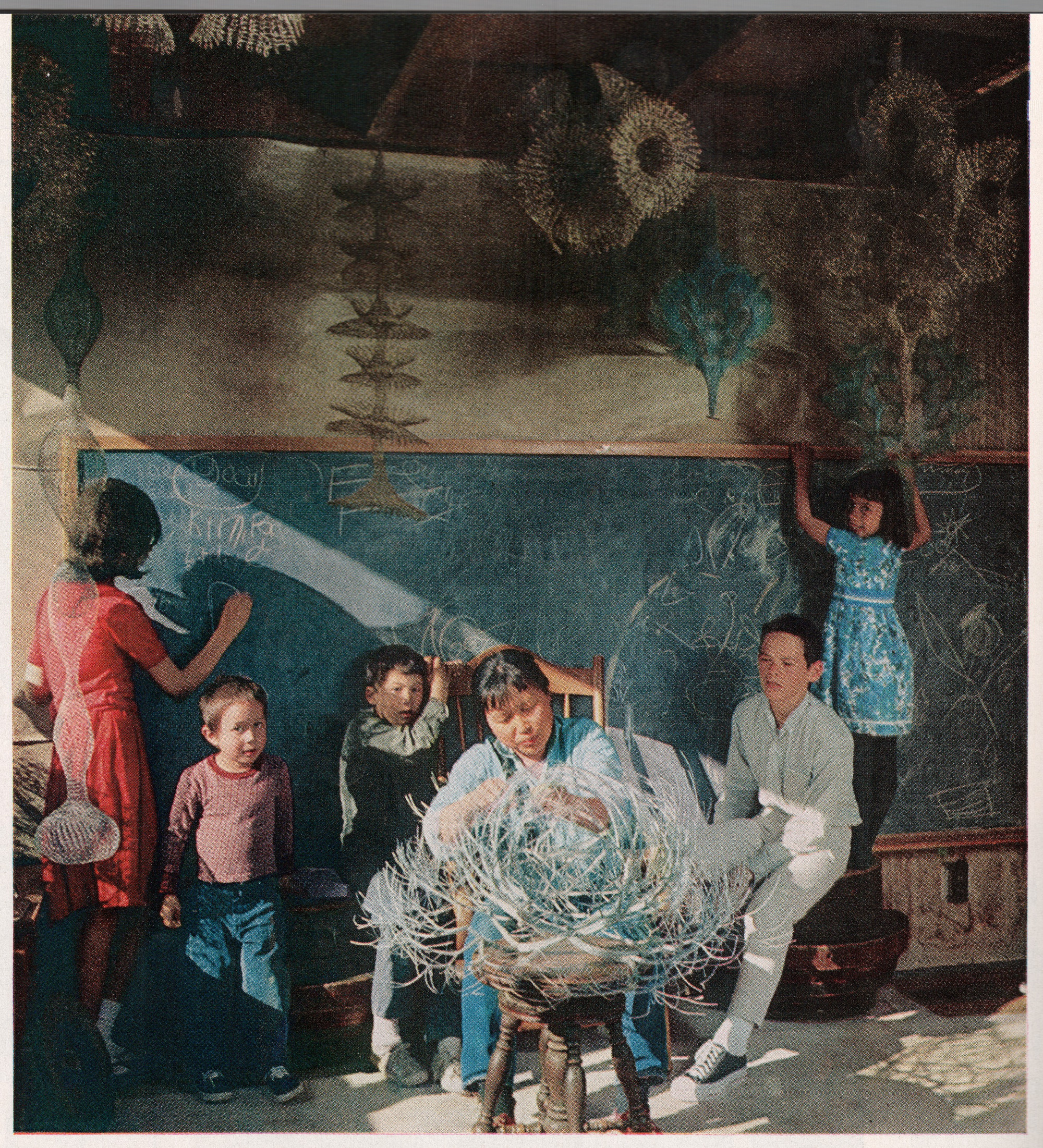

This period of material experimentation eventually led Asawa back to education. In 1968 she and a fellow parent founded the Alvarado School Arts Workshop, a program that brought professional working artists, gardeners, and parents into schools. Through art classes Asawa taught children how to fold origami and sculpt baker’s clay figures using simple materials to reinforce the idea of doing more with less, while encouraging students to observe and experiment. “I would like the children to have an area where they can make decisions about design, materials, and what they do; that’s really the first step in problem solving.” This became the foundation of her teaching ethos, once again invoking Black Mountain.

Asawa’s experience at Black Mountain grounded her creative practice and guided her unconventional path to education by teaching her how to listen to the materials she had on hand and refine her ideas through experiments with line, folds, and manipulation. “The material is irrelevant,” Asawa once said. “You take an ordinary material like wire and you give it a new definition. I’m interested in what it can do by itself and that’s what excites me . . . It’s the distance between effort and effect.” Traversing that line both in life and her art, Asawa gave shape to new ideas and innovative forms, methodically meandering in mesmerizing ways.

Ruth Asawa teaching a Baker’s Clay demonstration at the San Francisco Museum of Art (now San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), California, 1973. Photograph courtesy of Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

Ruth Asawa teaching origami to elementary school students. Photograph courtesy of Ruth Asawa Lanier, Inc.

Support the Oxford American

The Whiting Foundation will double your donation—up to $20,000.

Your donation helps us publish more work like the article you're reading right now. And for a limited time, every gift will be matched up to $20,000 by the Whiting Foundation.

Prefer a subscription? You'll receive our award-winning print magazine—though subscriptions aren’t eligible for the match.