Saving the Largest Collection of Appalachian Culture

Floodwaters damaged Appalshop’s media archive. Now, federal funding cuts are threatening its restoration.

By Caroline McCoy

Unidentified Flood-Damaged Appalshop Film preserved by Colorlab in Maryland, Courtesy of the Appalshop Archive

Over five days in July of 2022, a series of thunderstorms drenched eastern Kentucky, dropping as much as four inches of rain per hour and causing record-breaking flooding of the area’s river system. Forty-three people died and more than thirteen hundred required rescuing by helicopter or boat. Roughly nine thousand homes were damaged or swept away entirely, as were roads and businesses.

In Whitesburg, a town snaked through by the North Fork of the Kentucky River, the waterway rose nearly seven feet higher than it had in 1957, during the previous flood of record. Floodwaters rushed down Main Street, damaging various structures that formed the cultural center of town, including the building that housed Appalshop, a creative and educational institution for film, radio, theater, and the arts of Appalachia. The organization is a longtime friend and sometime collaborator of the Oxford American. A mutual interest in the music, art, and culture of Appalachia inspired a 2017 profile of WMMT, Appalshop’s community radio station that has been showcasing real Appalachian voices since 1985. The OA has also featured projects by youth filmmakers who have attended Appalshop’s Summer Documentary Institute.

Much of the organization’s work is sustained by government funding, with eighty-five percent of the Appalshop Archive budget coming through federal grants. After the flood, that money not only continued to support community programing—WMMT barely missed a beat, moving its studio to a Winnebago nicknamed the Possum Den—but also paid for the restoration of Appalshop’s deep archive of Appalachian media—the largest in the world—most of which was damaged by floodwaters.

In the wake of federal funding cuts, including the loss of a quarter-million-dollar NEH grant, Appalshop has been forced to pause some of its restoration work. “For years [federal support] has been a strong point of our archive,” said Chad Hunter, Appalshop’s archive director. “It really has driven our work and allowed us to achieve what we have. But now that’s become a liability. So all of a sudden, we’re scrambling to find other funding sources.” Hunter estimated that roughly sixty percent of the Appalshop collection is still in need of restoration, a task that becomes more difficult as time passes. “The collection continues to deteriorate as we speak, and there is a finite window on it,” he said. “So, the longer we wait, the more we’re going to lose.”

Appalshop was founded in Whitesburg in 1969 as part of a nationwide initiative to bring media-related job training to rural and disadvantaged youth. Since then, it has evolved into an epicenter of Appalachian storytelling, with film and photography workshops, traveling theater productions, a literary journal, a record label—June Appal Recordings—the WMMT radio station, an annual music festival, and the archive, which houses thousands of artifacts related to Appalachian cultural history.

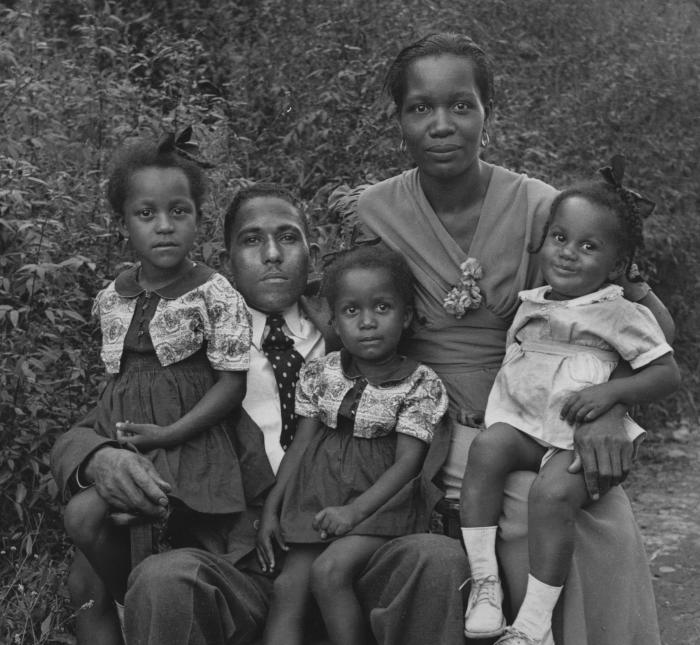

The Appalshop Archive began in 2002 to preserve and promote access to works produced by Appalshop artists, including documentary films and original recordings featuring musicians such as Hazel Dickens, Lee Sexton, Ralph Stanley, and Nimrod Workman. (Appalshop’s Nimrod Workman collection was recently added to the National Recording Registry by the Library of Congress.) The archive also houses donated collections, including an impressive number of original negatives by William R. “Pictureman” Mullins, a commercial photographer who documented everyday life in eastern Kentucky, southwest Virginia, and Baltimore, Maryland.

From 1979 until the flood of 2022, Appalshop was headquartered in a three-story wood-planked building on Whitesburg’s Main Street. The former bottling plant appealed to the organization’s founder, Bill Richardson, who relied on his architecture background to convert the space. By the time of the flood, the building held recording studios, the radio station, a main stage for theater performances and monthly bluegrass concerts, offices, and an expansive warehouse devoted to the Appalshop Archive.

When the floodwaters receded, employees and volunteers returned to the building to assess the damage. At the time, Chad Hunter, who helped start the archive, was no longer employed by Appalshop; but he drove from his home in Pennsylvania to assist then-Archive Director Caroline Rubens. “It was just an unbelievable mess,” he said, describing soggy paper collections, film reels and cassettes caked in mud and silt, and a waterline that reached as high as eight feet along the warehouse walls. “There might have been, like, two shelves at the very top that weren’t underwater.”

Hunter played an integral role in the sorting and early preservation efforts of Appalshop’s flood-damaged artifacts, acting first as a volunteer and then as a consultant. Since his return to full-time work with the organization as its archive director, he has devoted much of his energy to coordinating restoration work. The flood-damaged items vary in kind and scale. Recently, community fundraising paid for the restoration of an assortment of handmade quilts, a banjo that once belonged to Lily Mae Ledford, two wooden sculptures by the Virginia-born artist Fred Carter, and a rocking chair and dining set crafted by the Kentucky furnituremaker Chester Cornett, whose designs have sat in the White House.

Efforts to repair damage to the vast store of multimedia collections—many of which were slated for digitization before the 2022 flood—have been more complex, time-consuming, and expensive. To avoid further degradation, paper and photographic collections required freezing and cassette tapes had to be opened and dried by commercial-grade dehumidifiers. Film reels, on the other hand, needed to stay wet to prevent the separation of the base and emulsion layers. These reels were rinsed with water, sealed in garbage bags, and loaded onto refrigerated trucks.

Unidentified Flood-Damaged Appalshop Film preserved by Colorlab in Maryland, Courtesy of the Appalshop Archive

“Eventually we’ll lose it all, if we don’t do anything.”

Appalshop coordinated with restoration specialists across the country, shipping film, video, audio, and photographic collections to labs in Maryland, New Jersey, North Carolina, and Massachusetts. Because of the volume of material and the time it takes for each lab to restore and digitize a single piece of media, Appalshop also required cold storage for a large quantity of items. That space was donated to the organization by Iron Mountain, in Pennsylvania. A smaller selection of items sits in freezers at Appalshop’s temporary offices in Jenkins, Kentucky. The old Appalshop building in Whitesburg, Hunter said, is squarely inside the newly delineated floodplain. “There’s no way for us to continue to inhabit that.”

Amid much uncertainty, Appalshop began to receive good news from its lab partners. “While we thought we may have lost the whole collection, it turns out we can save most of it,” Hunter said. Without funding to pay for that restoration work, though, many materials remain at risk of degrading beyond repair. “Eventually we’ll lose it all, if we don’t do anything,” Hunter said.

Included among the already restored items are the William R. “Pictureman” Mullins negatives—roughly 3,600 photographs that Appalshop partnered with the Northeast Document Conservation Center to rescue and digitize—as well as video interviews, documentary footage, and audio recordings. In one salvaged video, bluegrass musician Hazel Dickens performs in Clintwood, Virginia. In another, members of the East Kentucky Social Club trace their heritage to African-American coal-mining communities. And in an audio recording captured during the funeral of bluegrass fiddler Curly Ray Cline, Ralph Stanley sings his tribute.

These salvaged records of Appalachian history are just a sampling of what has been—and what remains to be—restored and returned to Appalshop’s archive. To help celebrate and showcase these important works, the OA is once again collaborating with Appalshop. In the weeks to come, contemporary musicians and artists will be spotlighting the flood-salvaged recordings that inspire them. This four-part series explores the influence of Appalachian voices on American culture and the resonance of one region’s past with our collective present. As the singer-songwriter Will Oldham writes in a forthcoming essay, “Time is a human construct, and the deconstruction of this force through attention to what we call ‘history’ is our responsibility.”