Rehearing Skynyrd’s Soul

Listening carefully to “The Ballad of Curtis Loew”

By Carter Mathes

Lynyrd Skynyrd live in Rotterdam, Netherlands, October 16th, 1975. Photo by Gijsbert Hanekroot via Alamy

This exclusive feature is an online extension of the OA’s annual music issue. Order the Ballads Issue and companion CD here.

As a teenager growing up in the 1980s on one of the northern edges of the South just outside of Washington, D.C., Lynyrd Skynyrd’s sound surrounded me. It wasn’t that I was particularly deep into their music, but I appreciated their hard-driving electric guitars and the way that much of Skynyrd’s approach built upon elements of the blues and funk I was also being drawn to. At the time, though, I was more immersed in the very different guitar sounds of D.C. hardcore from bands like Minor Threat, Dag Nasty, and eventually Fugazi; the more bluesy, funky elements that I was hearing in D.C. Go-Go bands like Chuck Brown and the Soul Searchers, Rare Essence, and Trouble Funk; as well as old-school rap music and ’80s r&b (Chaka Khan 1984 album I Feel For You was my very first CD purchase). But I was regularly hearing Lynyrd Skynyrd in the car and on my shower radio through the iconic rock airwaves of DC101 and Q107, and the band’s music took on a new register to my ears and my mind by the time I was a college student in Virginia during the early 1990s, watching and listening to white students playing “Sweet Home Alabama” in hopes of nostalgically representing and projecting their imagined, constructed, and perhaps desired ideas of Southern identity. It was only much later in life—maybe twenty years ago, when I had the opportunity to listen to Skynyrd’s archive more deliberately, driving on Route 3 with my wife’s cousin in Spotsylvania, Virginia—that I encountered what has become for me one of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s most intriguing and underappreciated songs: “The Ballad of Curtis Loew.”

Despite existing as somewhat of a footnote in the deep and rich early musical history of Lynyrd Skynyrd, “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” remains one of the band’s more complex songs—sonically, lyrically, and thematically. First appearing in 1974 on the band’s sophomore album, Second Helping, “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” is the lyrical account of a virtuoso black man who exists on the margins, cast aside and undervalued by a community unwilling to acknowledge his talent and worth, refusing to grant him his due. The song was reputedly played live on only one occasion before the 1977 plane crash that took the lives of band members Ronnie Van Zant, Steve Gaines, and Cassie Gaines. I heard the song for the first time on that car trip, decades after its origin, having always appreciated the sound of Lynyrd Skynyrd but often with an ambivalence or uncertainty about the ways that the band’s cultivated image seemed to signal some kind of identification with white supremacy (no matter how misguided and out of the hands of Lynyrd Skynyrd this factor may or may not have been). Hearing “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” in this moment became an opening, if not a revelation, for me to re-listen to Lynyrd Skynyrd’s early work to consider the ways that black music impacted the band’s sound. This series of encounters with Lynyrd Skynyrd’s music has led me to wonder: Can this ballad be heard and experienced as a strangely beautiful ode to the black musical lineage which the band was sometimes tacitly and at other times more deliberately honoring, but was ultimately never able to fully explore or more pointedly repay?

“The Ballad of Curtis Loew” is a song of remembrance and elegiac celebration, co-written by Ronnie Van Zant and Allen Collins, but clearly voiced from Ronnie Van Zant’s lyrically fashioned perspective of a young boy who is focused on the profound influence the mythic Curtis Loew exerts on his musical consciousness. Yet within that framework, the song can simultaneously be heard as a broader philosophical and social commentary on the disregard and amnesia built into a white southern and white national consciousness, a mindset marked by a refusal to recognize and celebrate the entanglement between blackness and southern music.

The song tells the story of a young boy (“maybe I was ten”) who searches for soda bottles to cash in at the country store so that he can give money to a black man named Curtis Loew, who uses it to buy the wine he drinks while playing blues songs for the boy on his old Dobro guitar. In the catalog of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s thick, churning swamp music, “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” is somewhat set apart by its relaxed, almost plaintive sound, initially shaped through the sliding, elongated guitar licks and the relatively soft but still raspy tones of Ronnie Van Zant. The sounds of the ballad seamlessly mirror the story being told, gently increasing in intensity across syllabically measured quatrains that punctuate the boy’s memories of Curtis, ultimately landing on one of the song’s more intriguing couplets, which suggests the indivisibility of the blues and Curtis Loew's life: “Well he lived a lifetime playin’ the black man’s blues / And on the day he lost his life that’s all he had to lose.” The chorus neatly condenses the narrative core of the song: the boy’s deep desire to listen and learn at the hands and feet of Curtis Loew, and his critique of those who call Curtis Loew “useless” and fail to see the brilliance of his musicianship. The sentiment is echoed in the recurring couplet: “People said he was useless, them people all were fools / 'Cause Curtis Loew was the finest picker to ever play the blues.” Listening to this ballad, which is placed at the midpoint of an album opened by another ballad of sorts—“Sweet Home Alabama,” a song at the center of debates regarding the possibility of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s allegiance to and promotion of a white Southern identity that is uncomplicatedly tied to a recent segregationist past—it is striking that, for the past half-century, “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” has been largely overlooked within discussions of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s racial politics.

Given the curious, close-to-invisible singularity of “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” in Lynyrd Skynyrd’s oeuvre, how and why did Ronnie Van Zant choose to create this sonic collage of memory and history? According to the frontman’s longtime friend and band biographer Gene Odom, the song was inspired by Van Zant’s memories of learning to play guitar under the influence of a musically talented grocery store owner named Claude Hamner from Van Zant’s Westside Jacksonville, Florida neighborhood, and by his experiences listening to the bluegrass playing of Shorty Medlocke, the grandfather of bandmate Rickey. Odom, who has written extensively about the background contexts informing “Curtis Loew,” points to the ways that the song extends beyond simply memorializing the musical influences of Hamner and Medlocke to reflect Van Zant’s desire to create a composite of “every front porch picker he’d ever heard or had even heard of,” and to pay homage to the “many talented blues artists [who] had never had the opportunities he had, simply because they were black.” Thinking about Odom’s perspective on Van Zant’s role in composing the lyrical arc of the song within and against its poignant, winding, elegiac, and at times hard-rocking sound might amplify what I hear as Van Zant understanding not only that the blues roots of Southern rock were anchored in black sonic culture but that his ballad might serve as a counter to those all too willing to disregard this fact.

We’ll never know Van Zant’s exact opinions on the extent to which this ballad may have been intended as a reflection on how black music intersected with and helped to profoundly shape the sound of Lynyrd Skynyrd. But listening carefully to the ballad and examining its obvious and more ephemeral implications provides some leads that might help us—if not rethink the band’s legacy in twentieth century American music culture, then at least understand how complicated sonic histories can resound in unpredictable ways and create meaning where we sometimes least expect to find it.

It is worth noting that Van Zant was clear in seeing himself and his working-class Jacksonville community as “street people” and “common folk,” terms that Van Zant refers to in a 1976 interview with Jim Ladd. The comment was in response to Ladd asking Van Zant about the relationship between Lynyrd Skynyrd’s music and the idea that the band might function as a beacon of post-civil rights Southern pride—the “intense thing about being from the South,” as Ladd puts it. After a pause and slight intake of breath, Van Zant, in his calm, deep, slightly gravelly voice, explains to Ladd that this sense of identification as common people “straight off the streets” propels the simplicity of Skynyrd’s music:

Basically, Jim, we try to write common songs for the common people, for the street people. Not get way out there on a limb somewhere because I think you can relate to more people if you just write simply and write something with a hook line (is what we call it in the business). You’ll reach more people that way than if you do it the other way. I’m not putting down the other way . . . I don’t care for the fancy music, man. You can’t cut the rug to it.

What Van Zant is referring to as “fancy music” isn’t entirely clear, but as if to emphasize his point (and simultaneously drawing upon his reference to “cutting the rug”), the soundscape of the interview unfolds seamlessly into the straight-ahead opening chords of “Gimme Three Steps.” Forty-five seconds of funky, winding guitar wordlessly anticipate Van Zant’s first-person lyrical rendering of getting caught dancing with a woman whose lover has come looking for her, and of trying to escape the situation without getting killed by asking for a head start out of the club before shots might be fired. Guitarist Gary Rossington has recounted the actual events that transpired at Jacksonville’s West Tavern when Van Zant found himself in the situation that would become the basis of the song:

Ronnie went into a bar to look for someone and me and Allen were too young to get in so were waiting for him outside, and we were waiting and waiting, then he came running out with a big ol’ guy chasing him, yelling . . . The guy had a gun and he was a redneck and he was drunk—a nasty combination of things—and Ronnie said, ‘If you’re going to shoot me, it’s going to be in the ass or in the elbow.’ And he took off like a bat out of hell.

Rossington’s telling of the events that gave rise to the song—which he said was written in the car as the band members drove away from the tavern—further underlines what we might think of as the blues lyrical narrative functionality of the track: the way that the sonic world of the composition is drawn from real-life existential precarity and possibility. “Gimme Three Steps” is both an apt representation of music for the common folk in its lyrical directness, and a composition situated inside the tradition of Southern murder ballads, recalling the setting of a foundational example of the form, “Stagger Lee,” only shifting the context of a barroom dispute over a dice game to a woman.

“Gimme Three Steps” begins to show how certain elements of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s formative Southern rock explorations reflect the proximity and indebtedness of the band’s sonic aesthetic to the saturation of black sound throughout the Southern musical ecology that Skynyrd’s swamp music moves within. The third track on Lynyrd Skynyrd’s debut album Pronounced Lĕh-'nérd 'Skin-'nérd, “Gimme Three Steps” sits in a sequence—starting with opener “I Ain’t the One” and continued through “Things Goin’ On,” “Mississippi Kid,” and “Poison Whiskey”—that loudly pronounces different blues and funk contours within Skynyrd’s sound. Listening closely to “Gimme Three Steps,” we can also hear Van Zant’s lyrics being subtly underlined and punctuated by the bongo playing of Ms. Bobbye Hall, the legendary Motown percussionist credited with session work for Bill Withers, Carole King, Dolly Parton, the Temptations, Marvin Gaye, Janis Joplin, Bob Dylan, Stevie Wonder, Joni Mitchell, among hundreds of other musicians from the 1970s through the present. Two tracks later, on “Things Goin’ On,” we can hear Ms. Bobbye Hill again, this time rhythmically adding tambourine beats to the Dr. John–like piano sequences, funky walking bass lines, and gravelly blues guitar framing the song, which is perhaps the only Skynyrd composition outside of “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” to directly allude to race—or at least to conditions that most listeners whose consciousnesses had been imprinted by the turbulent late 1960s and early 1970s would likely associate with black struggle and the economic hardships of black life. Van Zant’s measured refrain resonates from the post-civil rights era context of its creation into the present contexts of racial and economic inequality that have persisted well past Van Zant’s call to awareness: “Well, have you ever lived down in the ghetto? / Have you ever felt the cold wind blow? / Well, if you don't know what I mean / Won't you stand up and scream? / Cause there’s things goin’ on that you don’t know.”

“Things Goin’ On” and “Gimme Three Steps” were first produced and recorded at the legendary Muscle Shoals Sound Studio in Sheffield, Alabama in 1971 and 1972, shortly after Lynyrd Skynyrd had signed on with manager Alan Walden. Alan—the brother of Allman Brothers manager Phil Walden and his sibling partner in Macon, Georgia’s Capricorn Records—brought Lynyrd Skynyrd to Muscle Shoals to record with Jimmy Johnson, a member of FAME studio’s Muscle Shoals Rhythm Section, the Swampers, and co-founder (with his bandmates, and with the backing of Atlantic Records producer, Jerry Wexler) of Muscle Shoals Sound Studio. Across the early FAME work of Jimmy Hughes; the iconic recordings of Aretha Franklin and Etta James; the coming together of Wilson Pickett and Duane Allman in 1968 to record Pickett’s Hey Jude album; and hundreds of other classic soul, r&b, and rock recordings, the racially and culturally dynamic sonic richness of Muscle Shoals and northern Alabama was certainly a flashpoint in the production of Southern Soul—a genre that was both pulling deeply from black traditions and putting those sounds in conversation with the talents of young white men committed to exploring, alongside fellow musical travelers across racial lines, the profound ways in which this palette of black Southern sound informed their understandings of what music was and could be.

Although “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” was not one of the tracks recorded during the early 1970s Muscle Shoals sessions with Jimmy Johnson, it was at this juncture—and in this space of black musical creation and expansion—that Lynyrd Skynyrd learned the finer points of studio musicianship and song production. The seventeen songs the band recorded at Muscle Shoals Sound Studio were ignored by a slew of major label record execs who Johnson and Walden presented the work to in hopes of garnering a record deal that would have established the young band within the musical world of the early 1970s, with Muscle Shoals Sound as their home studio. Instead, except for a handful of tracks that would appear on the band’s 1973 debut, including “Free Bird,” the original Muscle Shoals recordings would only be presented to the world roughly six years after being recorded and one year after the 1977 plane crash that tragically foreclosed the band’s history, as the posthumous album, Skynyrd’s First . . . and Last, before being repackaged and expanded two decades later as Skynyrd's First: The Complete Muscle Shoals Album. Despite the early unrealized attainment of a major record label contract while recording with Johnson at Muscle Shoals, the experience of working, learning, and honing musical craft in northern Alabama’s sonic ecology of black sound imprinted on the band, an impact testified to in lyrics from “Sweet Home Alabama”:

Now Muscle Shoals has got the Swampers

And they've been known to pick a song or two (yes, they do)

Lord, they get me off so much

They pick me up when I'm feelin' blue, now, how 'bout you?

The shoals, as Tiffany Lethabo King writes in her recent work The Black Shoals, can be understood as a meeting point and fluid space of transformation where the aquatic and terrestrial meet, a “space of liminality . . . simultaneously land and sea,” and as a metaphor for thinking about the entanglements of indigenous and black cultures in the Americas. In the cosmology of the Yuchi people, the original inhabitants of northern Alabama, the geologic-aquatic formation of Muscle Shoals along nunnuhsae, or “the singing river” (the body of water that would come to be known as the Tennessee River), contains the spirit of a young woman who projects her melodies along the water. Jimmy Cliff, who recorded at the studios in the early 1970s, speaks of this mystical Muscle Shoals soundscape as having a distinctive “field of energy” inspiring many of the musicians who have produced and recorded work at FAME and Muscle Shoals Sound.

This confluence of land, sound, and the often unrealized magic of southern U.S. cultures is at the core of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s music, and can be heard in the way that “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” flows between the instrumental sounds and lyrical narration that offer impressions of the almost ecstatic state of sonic release experienced by Loew, who “did not have a care” while immersed in song and wine, and the wonder and communion experienced by Van Zant’s projection of himself as he repeatedly encounters Loew’s command of sound firsthand—even though he knows the cost of his communion is repeated beatings at the hands of his mother, who he recalls would “whoop me” every time he would “go see him again.” The young boy’s mother—along with the others in the community who ignore and denigrate Loew until “the day old Curtis died,” a day when “nobody came to pray”—view Loew as “useless,” and perhaps even dangerous, because his virtuosity refutes the false narratives they have constructed to ignore and devalue the black creative energy propelling the dynamic power of the blues. Van Zant underlines this point with his own lyrical poignancy, conveying how instead of the community honoring Loew’s musicianship on his passing, an “Ol’ preacher said some words and they chunked him in the clay.” His burial reflects the desire to erase any trace of his greater significance as a black musician, one who was charting ways of knowing and experiencing the world through his guitar and an understanding of what James Baldwin terms “the experience of life, or the state of being, out of which the blues come.”

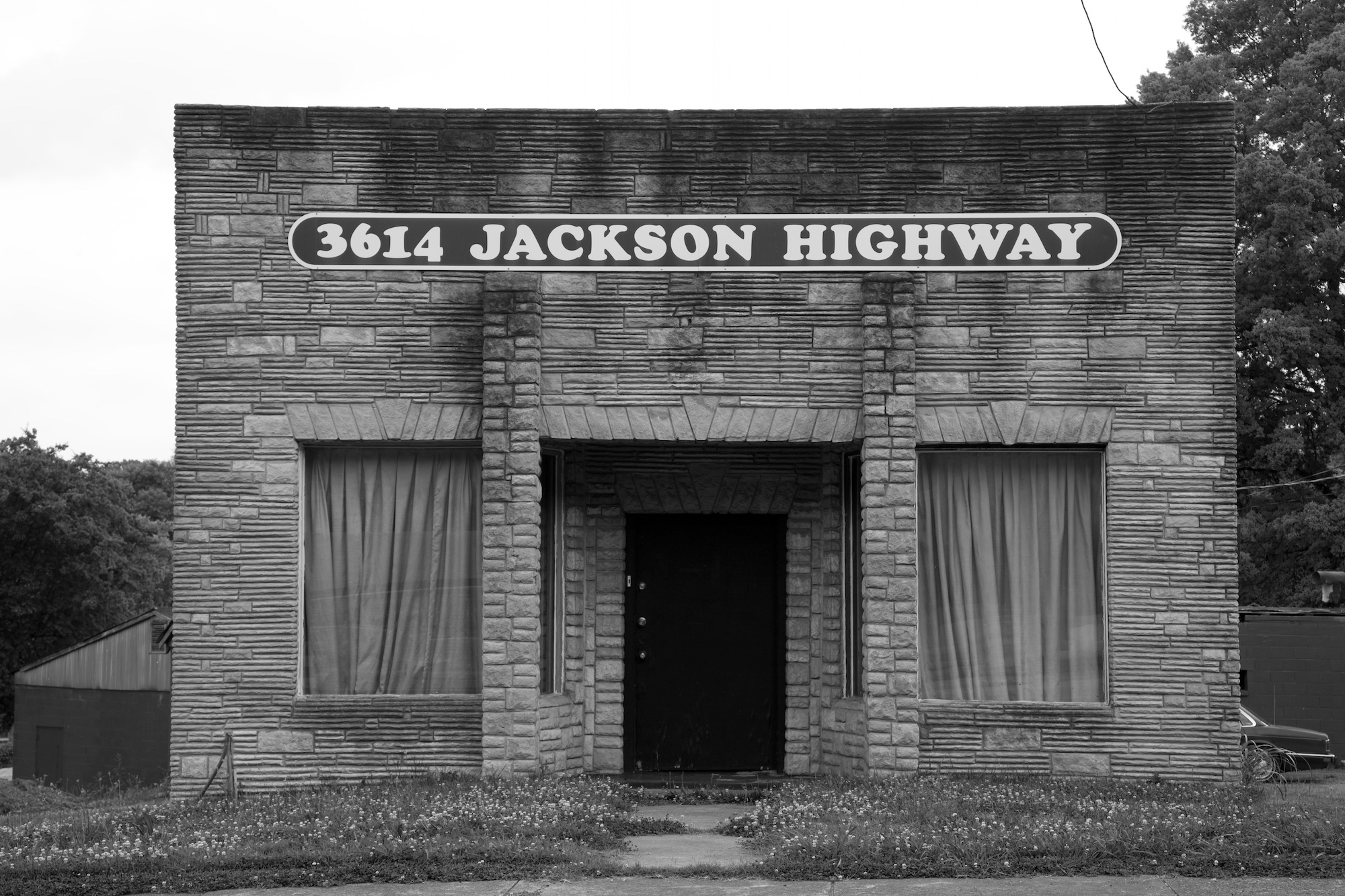

Muscle Shoals Sound studio, 3614 Jackson Highway, Sheffield, Alabama. Photo by Carol M Highsmith. Courtesy Library of Congress

In his recent study of mid-twentieth century U.S. Southern culture, The South of the Mind: American Imaginings of White Southerness, 1960-1980, Zachary Lechner contends that, “Southern rock was a sound—an amalgam of blues-rock, rhythm and blues, and country—but it was also a statement about the meaning of the white South. White Southern pride was a major theme of the music, but like other imaginings of the South in the post-civil rights era, its purveyors (and to some extent, fans and national commentators) also predicated the value of white Southernness as a solution to national ills.” Lechner’s point rests partially on the distinction that he and others make between the images and impacts of Lynyrd Skynyrd and the Allman Brothers Band—in terms of Skynyrd representing what he terms “rebel macho,” while the Allmans reflect a countercultural alternative to more dominant attempts to “recover” Southern white masculinity in the post-civil rights era. I can understand Lechner’s (and those he echoes) desire to break this musical and cultural history down along these lines, yet when we listen deeply and follow the winding contours that compositions such as “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” reveal, we can listen through the cracks that disrupt neatly demarcated histories and truly engage in the work that art asks of us: enabling our imaginative and critical lenses to better understand how the stories and representations might convey realities that escape more linear forms of telling.

The narrative indirection at play in “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” is shaped by the collaboration between the power of the song’s sonic narration and the hungry ears and mind of the listener. Perhaps the most telling point that the song conveys is the critical awareness of what James Baldwin referred to as the “state of carefully repressed terror,” a phrasing that for Baldwin explains how white consciousness in the United States has generally been shaped in relation to the presence of black people. Van Zant’s refrain—“People said he was useless, them people all were fools / 'Cause Curtis Loew was the finest picker to ever play the blues”—consistently brings us back to this point, and importantly shifts in its last iteration from Van Zant’s third-person storytelling to directly frame his memory of Loew against his community’s refusal to acknowledge this black man’s musical gifts, crooning as the song fades, You’re the finest picker to ever play the blues. The lyric says so much beyond the deceptive simplicity Van Zant imbues it with, pointing to elements of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s legacy that upset the neatly marketed construction of their image in support of a reimagined and defiant white South reclaiming itself in the wake of the civil rights movement. We can clearly see the ways that the project of reclamation and the tensions around it continue well beyond the 1970s creation of “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” into our musical and political present.

I was struck recently by how deeply this recent history keeps leaking into our present sense of what Southern rock was, is, and might be. As a fan of Chris Stapleton’s music and admiration of his clear indebtedness to r&b and blues traditions, I’ve watched and listened as his popularity has grown within a musical enviornment in which his long-haired rebellious image seems to all-too-perfectly fit the ideal of what many white people want Southern rock to be, seemingly in spite of his sound. This point felt driven home in the summer of 2023 at a Stapleton show in upstate New York that I attended, where I was one of a handful of black folks. While I’m sure that the crowd included many who were appreciative of the black musical foundation in Stapleton’s music, the dissonance between the sounds and sights of the evening were striking to me. During the performance, I thought about Stapleton’s bluesy, soulful sound alongside his tribute cover of Aretha Franklin’s “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man,” his performance with Jennifer Hudson at the CMA awards, his welcoming of The War and Treaty onstage to perform “Tennessee Whiskey” (as well as their covering of his song “Cold” to honor his receiving the CMA Triple Crown Award), and his outspoken support for Black Lives Matter. It is clear where Stapleton’s sound comes from, who he gives thanks to for it, and how he wants it to be heard—yet at this particular event I was feeling like none of that mattered to most in the crowd. Then, as he played a moving cover of “Free Bird” that fused into one of his own songs, “The Devil Named Music,” I thought about Stapleton’s tribute as a parallel that bridges a certain Southern rock tradition building on Skynyrd’s sound and image, but also tapping into the ways that “Free Bird,” in the words of Ronnie Van Zant, is “about what it means to be free, in that a bird can fly wherever he wants to go . . . Everyone wants to be free. That’s what this country is all about.” Is it though?

Lynyrd Skynyrd and Chris Stapleton seem linked in this paradoxical situation of making music influenced by black sounds with respect for the traditions they are drawing from, but as white men in a white supremacist society that wishes to hear their music as evidence that there really is a truth to whiteness as something distinctly unto itself, and that this mythic property can somehow be heard in music like Southern rock. After reflecting on what I was hearing and seeing at the concert, and the ways that the scene brought Lynyrd Skynyrd’s music and possible meanings into the present moment, I felt that we could do well to honor the sounds of “The Ballad of Curtis Loew” and the many facets of Lynyrd Skynyrd’s complex legacy that continue to reverberate like the finger-plucked notes of Curtis Loew’s Dobro, echoing through the streets of a small country town and across the ongoing breadth of our post-civil rights history.