Memphis Blues Again

By Peter Guralnick

I had never been South before.

My brother and I set out for Memphis in a Volkswagen that lost its clutch in Knoxville, and as we got closer, it seemed like I knew a blues lyric (“I’m going to Brownsville, take that right-hand road”) for nearly every town we passed. Our destination was the 1969 Memphis Country Blues Festival, which took place at the Overton Park Shell, where Elvis’s career had been launched fifteen years earlier. It was early June, hot, humid. Sitting on the old wooden benches at the Overton Park amphitheater, there was no escape from the sun.

But the music was magical: rediscovered (or recently discovered) blues legends like Bukka White, Furry Lewis, Reverend Robert Wilkins, Fred McDowell, Joe Callicott, and Sleepy John Estes, all in their sixties and seventies, were the stars of the show, along with an assortment of young white disciples like John Fahey, Sid Selvidge, and Johnny Winter. I had seen many of them before, certainly, in coffee houses and college concerts, but it was a different experience to see them for the first time in a steamier climate, and there was no question that the music benefited from the change. A new ten-album series on Fat Possum, developed in collaboration with Amazon Originals under the umbrella title of Worried Blues (most of the albums were originally issued in a limited edition by the Genes/Adelphi label in the nineties), presents the first three on that 1969 Memphis bill, plus such other luminaries as Skip James, Mississippi John Hurt, Houston Stackhouse, R. L. Burnside, and Honeyboy Edwards, all recorded in what appear to be relaxed, easygoing settings at the outset of their new careers. And yet in few cases did those careers live up to the expectation of either artist or audience. The gulf between anticipation and achievement was simply too great.

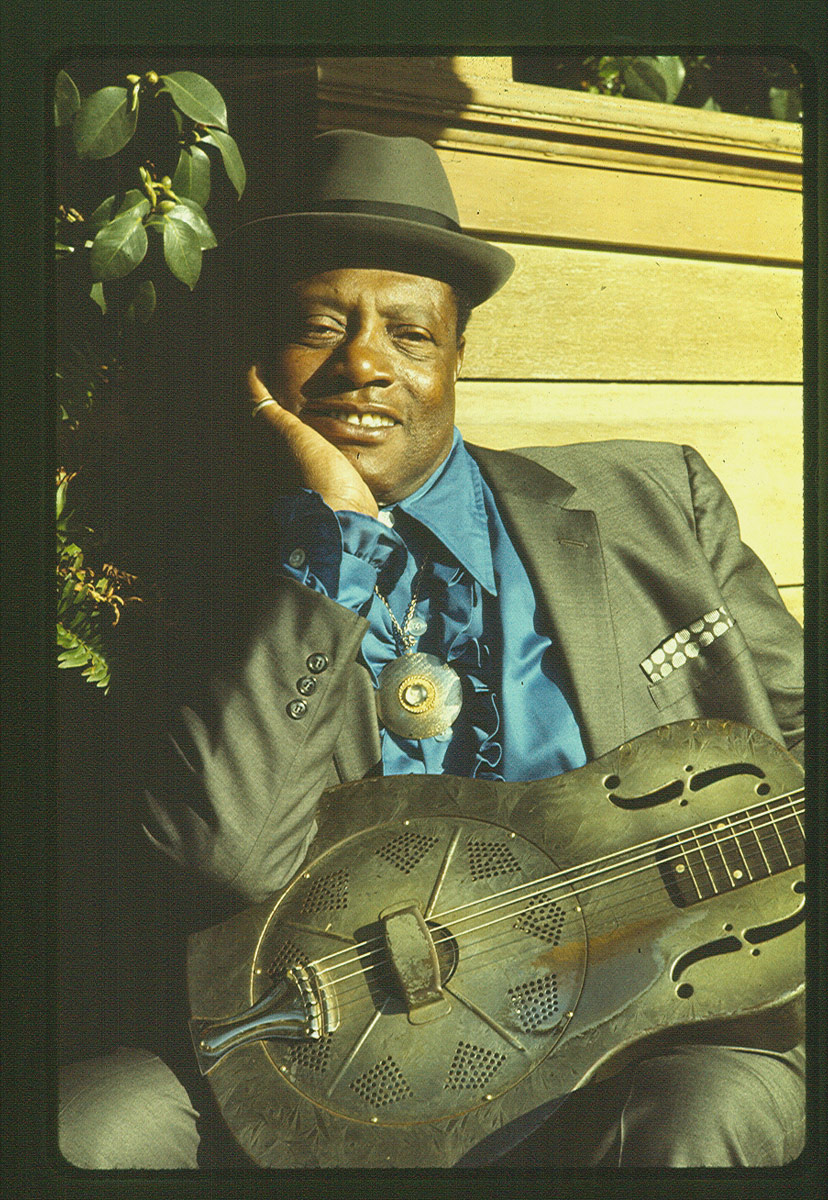

Bukka White, one of the towering figures of pre-war country blues, whose 1940 recordings rivaled the taut poetry and tightly controlled performances of Robert Johnson (his indisputable masterpiece, “Fixin’ to Die,” was featured on Bob Dylan’s first album), is a case in point. To his young cousin, Riley B. King (soon to become B.B.), his visits home, to Kilmichael, Mississippi, in the early ’40s were like the visits of a Hollywood star: “Razor sharp. Big hat, clean shirt, pressed pants, shiny shoes. He smelled of the big city and glamorous times; he looked confident and talked about things outside our little life in the hills.” But it was Bukka’s music that impressed his younger cousin most, the ability “to connect [his] guitar to human emotions,” a standard that B.B. would strive to uphold all his life. Bukka (more properly “Booker” as in “Booker T. Washington White”) was rediscovered in 1963, when guitarist John Fahey, a brilliant blues abstractionist who preferred to describe his music as “American Primitive,” sent a letter to “Bukka White (Old Blues Singer), c/o General Delivery, Aberdeen, Mississippi,” on no other basis than that White had proclaimed in one of his early recordings, “Aberdeen is my home / But the men don’t want me around.” As it turned out, the letter was forwarded to the Memphis boarding house where Bukka lived while working part-time in a tank factory, and his musical career, on hold for the last fifteen years, almost immediately resumed.

Bukka White, one of the towering figures of pre-war country blues, whose 1940 recordings rivaled the taut poetry and tightly controlled performances of Robert Johnson (his indisputable masterpiece, “Fixin’ to Die,” was featured on Bob Dylan’s first album), is a case in point. To his young cousin, Riley B. King (soon to become B.B.), his visits home, to Kilmichael, Mississippi, in the early ’40s were like the visits of a Hollywood star: “Razor sharp. Big hat, clean shirt, pressed pants, shiny shoes. He smelled of the big city and glamorous times; he looked confident and talked about things outside our little life in the hills.” But it was Bukka’s music that impressed his younger cousin most, the ability “to connect [his] guitar to human emotions,” a standard that B.B. would strive to uphold all his life. Bukka (more properly “Booker” as in “Booker T. Washington White”) was rediscovered in 1963, when guitarist John Fahey, a brilliant blues abstractionist who preferred to describe his music as “American Primitive,” sent a letter to “Bukka White (Old Blues Singer), c/o General Delivery, Aberdeen, Mississippi,” on no other basis than that White had proclaimed in one of his early recordings, “Aberdeen is my home / But the men don’t want me around.” As it turned out, the letter was forwarded to the Memphis boarding house where Bukka lived while working part-time in a tank factory, and his musical career, on hold for the last fifteen years, almost immediately resumed.

Certainly the recordings on the Fat Possum album, originally titled 1963 Ain’t 1962, and made within weeks of his rediscovery, retain some of the power of his early work, and there are evocations, as there would be on subsequent recordings, too, of influences like Charley Patton and contemporaries like Howlin’ Wolf. But it was clear at the same time that the knife-edge quality of his voice had coarsened, and the astonishing focus and fluidity of his songwriting and performance had ineradicably declined. And it was clear as well to anyone who had contact with the man that at fifty-four he was not looking for rediscovery; he was ready for the stardom that his cousin B.B. King had long since achieved. I think for me the most poignant manifestation of this dilemma came when I first saw Bukka, in the spring of 1964, as part of a folk series at the Boston YMCA, where the featured performer showed up for his Boston concert debut in a tuxedo, with little more than a dozen people in the audience (and not well-dressed ones at that) to applaud his performance.

With Skip James, the situation was somewhat different. Rediscovered in the Tunica County Hospital in June of 1964 by a trio of fans (once more including John Fahey), he was playing again, for the first time in years, at the Newport Folk Festival in July, his singular musical skills and imagination largely undiminished. He continued to develop his music, and even write new songs reflecting on his current situation, until his death five years later, but in a dark and characteristically introspective style that set him apart from almost every blues singer of his, or any other, generation. Playing in an open D-minor tuning that can best be described as “eerie” (it was a style that was confined almost entirely to his hometown of Bentonia, Mississippi, population then and now: less than 500), he sang fully thought-out and composed songs far removed from a blues mainstream that for the most part defines itself by fervor, not form. As a result, Skip never achieved anything like the popularity of many of his fellow rediscoveries, and it clearly ate at him to see the adulation that his good friend Mississippi John Hurt got from a young audience that was won over by the charm of both his personality and performance. And just in case you should have any doubts on that score, listen to the music on almost any of Hurt’s recordings, early or late—I defy you to resist the nimble finger-picking and winsome charm of such performances as “Richland Woman,” “Louis Collins,” and “Avalon Blues,” or his self-deprecating star turn at the end of the PBS series American Epic. To Skip, though, this was little more than “play-party music,” perfectly good for dances and country suppers, as Skip’s manager Dick Waterman put it, but “not to be taken seriously as ‘great blues.’” And just for the record, Mississippi John Hurt agreed; he considered Skip a “genius,” beyond any doubt. But on the other hand, you wonder just how much of John’s irresistible charm was that very agreeableness.

There were few moments of rest for Skip, it seemed—he was ill, and he was troubled— but I remember seeing him once with John at a Boston coffee house, where, in addition to presenting their own songs in separate sets, they performed together as well. The two songs that I recall were utterly . . . all right, charming: “Silent Night” (though you haven’t heard “Silent Night” until you hear Solomon Burke’s soaring, soulful version, recorded live in a Georgia church at the blazing height of summer) and Jimmie Rodgers’ epochal country (as in country music) blues “Waiting for a Train.” But let’s pause here for a moment, if only to recall all the different strands that go into all the different kinds of music. Jimmie Rodgers, as I’m sure everyone knows, was almost universally hailed as “The Father of Country Music,” and to all intents and purposes he was. And yet his music drew upon the most diverse sources, not the least of which was the ululating blues of Tommy Johnson, who (just to illustrate some of the complications endemic to every form of cultural transliteration) greatly influenced that purest of all blues singers, Howlin’ Wolf, who in turn cited as one of his greatest inspirations none other than . . . Jimmie Rodgers.

This was all, for me, in 1969, a vast unexplored land, and like every realm of the imagination it remains so to this day. There are always going to be new, or overlooked, or simply misconstrued, treasures to discover, there are always new and unexpected connections to be made. And I hope this is not beginning to sound like, There were giants that walked the earth in those days, and that with the passing of those giants this kind of music is no more. That isn’t what I mean at all. If you need a mantra, just remember the lesson of the Internet, nothing ever really disappears, and listen to the music of new champions of the old and new, like the North Mississippi Allstars Luther and Cody Dickinson, who learned at the feet of such legendary champions of the hill country style as R.L. Burnside and Junior Kimbrough and Otha Turner; listen to no less dedicated disciples like Dan Auerbach or Paul Burch or Colin Linden, or poetic practitioners like Kevin Gordon—and who knows how many more?

Because by now it should be clear there’s no end in sight. How could there be, unless we’re talking the twilight of the gods or the inescapable impermanence of the flesh? When I first came to Memphis in 1969, I did my best to imagine the world as it must once have been. A world in which Elvis’s performance of the Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup blues “That’s All Right” at the Overton Park Shell in 1954 stood out as a revolutionary act. And yet as I was later to learn, Elvis listened to the Metropolitan Opera, too, as a child. He went to Overton Park on many Sunday afternoons (“The same place that I did my first concert”) to hear the Memphis Symphony Orchestra play. While at the same time he was tuning in religiously to WDIA, the first all-black station in the country. And listening every night to DJ Dewey Phillips’ aptly named Red, Hot, and Blue show, which mixed r&b and pop, the sacred and the profane, the trivial and the profound for a black-and-white audience that competed in its fervor for both the music and its egalitarian champion. It took a long time for me to disimagine categories, but as Howlin’ Wolf said the first time we met, in response to one of those foolish questions we all tend to ask—like, What did he think of all these white kids, like the Rolling Stones, who had so recently adopted his music? Well, he said, he liked Paul Butterfield, “he grown up in it just like that other boy out in California, [who did] that ‘Hound Dog’ number.” You mean Elvis Presley? I finally managed to blurt out—I mean, I was caught. “Yeah,” said Wolf impatiently, as if the reference should have been obvious to anyone. “Elvis Presley,” he said, “he made it his way.”

Which only goes to show that nothing ever really changes. Marketing strategies (which, after all, is all that categories are) may rise and fall, but to the democratic listener they are beside the point. The music calls attention to itself, and then takes you somewhere else. It isn’t really any different than going to Memphis was for me in the first place. One thing inevitably leads to another, and before you know it, you are caught up in the ecstatic dance, the ecstatic trance of the music. But just remember: If you’re going to Brownsville, take that right-hand road.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.