Robert Lester Folsom: Take Two

The Georgia-born, Florida-based songwriter's career proves some dreams never die

By Michael Venutolo-Mantovani

Photograph courtesy of Anthology

There’s a stretch of road along the Ortega River that’s good for biking. It’s flat. Jacksonville is almost entirely flat. And the leafy oaks draped with Spanish moss block the brutal Florida sun.

It’s on this stretch of road during his daily bike rides—one loop before work, one after—that Robert Lester Folsom talks to God. Or maybe it’s where he listens for God. It’s not a long loop; just a few miles out and back from the home he shares with his second wife and his third daughter. He’s only gone a handful of minutes before he’s back home, in time to get to his work as a painter in the mornings, or to settle in with his guitar each evening.

But, then again, it doesn’t take Folsom long to connect with his God. After a life spent in the church, the conversation comes with ease. Sometimes on these bike rides, his mind drifts. Sometimes he’s looking at a ditch, remembering the simplicity of youth, where a ditch and a few playmates was all that was needed for a good time. Sometimes he’s thinking of the music he’s going to write. But often, he’s talking to God.

It was in the church that Folsom was raised: a Baptist church in a rural corner of Southern Georgia. It was in the church that he found himself after putting his dreams of being a singer-songwriter to rest in the early 1980s, when he was in his mid-twenties. The church was Methodist, at first. Then Folsom moved to a different church, non-denominational. It was here that he fulfilled the need that possesses musicians: the need to play their instrument with other people, to experience the cosmic and the kismet, the unspoken interplay of live performance, and the very real sense of electricity that bounces between people making music together. These days, he goes to Rise Church, a place some locals call a rock & roll church. But he doesn’t necessarily go there to pray. These days, he shies away from formal liturgy, preferring the freedom of his daily bike rides as a time to commune with his God.

If there’s one thing he does miss about going to a more traditional church, it’s the hymns.

When Robert Lester Folsom was a boy in Adel, Georgia in the late 1950s and early 1960s, it was the AM radio on his parents’ kitchen counter that first obsessed him. It was steadfastly tuned to a single station, programmed in concert with the rhythms of a family home: classic country in the early mornings before the kids woke; Top 40 as families ate breakfast; then, while the children were in school, gospel; country again before the kids came home; and finally, Top 40 once more.

Folsom remembers those days when he’d stay home sick from school fondly. It was on those days he’d be privy to the spiritual magic of gospel.

Like most people born in the Baby Boom, Folsom became obsessed with rock & roll. Specifically, the bands of the British Invasion. Beatles. Stones. Yardbirds. Hermits. Animals. Et cetera.

He was also lucky enough to be raised in a home with ceaselessly supportive parents. Folsom brokered a trade with a friend; his record player for their beaten, stringless guitar. At home, Robert Lester Folsom’s father cleaned up, restrung, and prepared the instrument for duty. Folsom’s parents, traditional church-faring, rural Southerners, embraced his burgeoning hippie sensibilities. In 1972, when he was seventeen, his parents allowed him to board a bus and spend a few weeks knocking around Nashville, armed with his guitar and a few tapes.

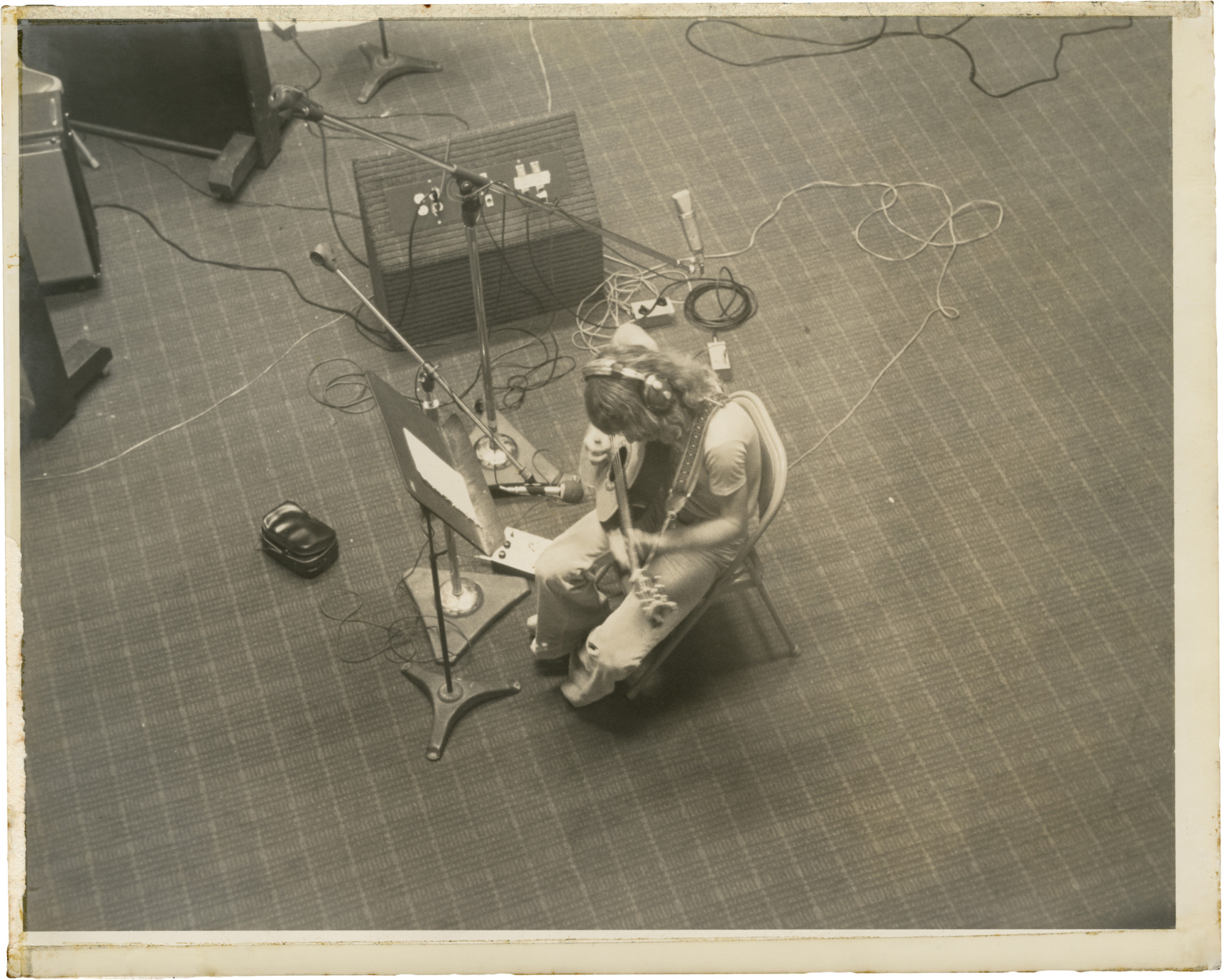

Those tapes were the progeny of Folsom’s craft as a songwriter and his obsession with a Sears 3440 two-track reel-to-reel tape recorder. He went in on the two-track with a friend, each contributing about seventy-five dollars. After a few weeks, Folsom, who quickly became obsessed with the 3440, offered to buy the friend out.

Soon, the 3440 consumed him the way The Beatles once had. Soon, he was enlisting friends and family, musicians and classmates to help him capture the sounds in his mind on tape. Soon, he became a master of bedroom recording, of homecooked overdubbing techniques generated by the creative constricts of only having two tracks on which to record.

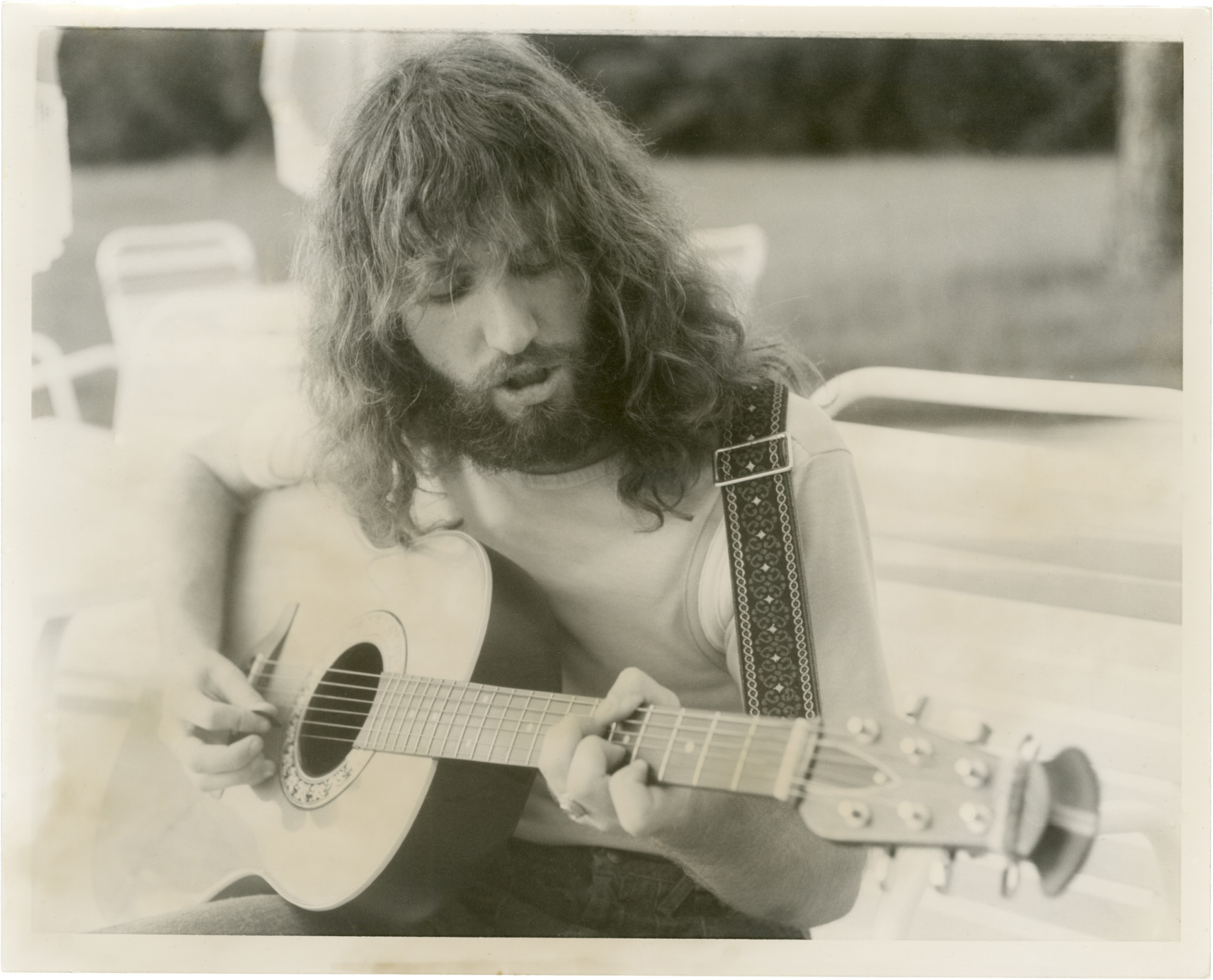

In Nashville, Folsom spent most of his time hanging out at the offices of Combine Music Publishing, the then-home of Kris Kristofferson on Music Row. The scrappy teenager—a typical long-haired, bearded hippie of the era—didn’t know anyone at Combine, didn’t have a single in. But for some reason he still can’t explain more than fifty years later, the staff made sure Folsom was fed and let him hang around their offices, all while he watched them turn away dozens of other hopefuls just like him. He thinks it may have had something to do with his tapes, which he believes impressed those Nashville producers who took him under their wings during his few weeks in town.

And they encouraged him to come back with more soon, when he was just a bit older. They recommended he finish high school first.

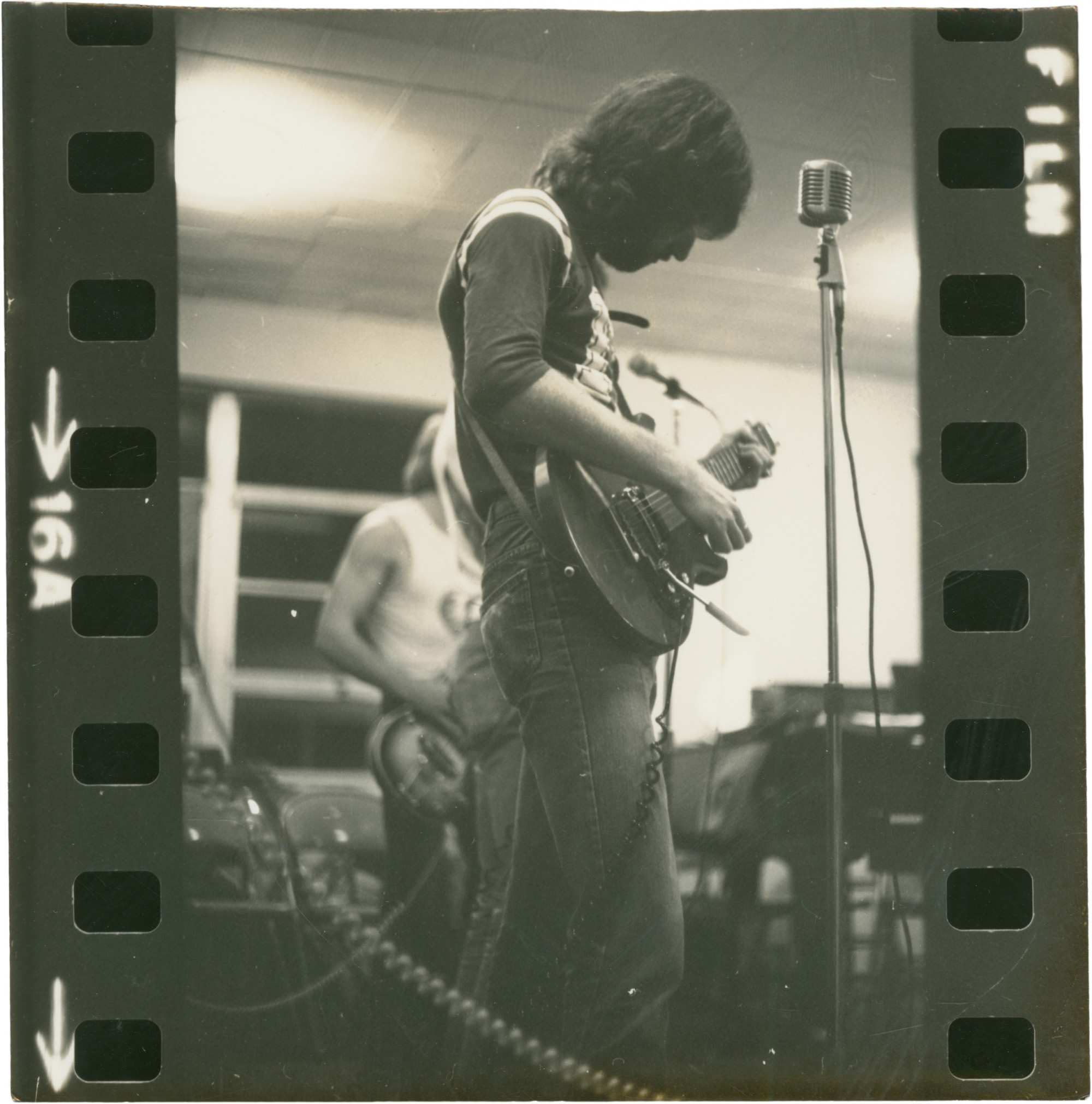

Photograph courtesy of Anthology

After a few years at South Georgia College, Folsom spent some time working in a Valdosta-based deer stand manufacturer, alongside a bunch of other hippies, none of whom hunted. He spent most of his time playing with Abacus, a progressive rock & roll band started with his high school friend and longtime collaborator Hans VanBrackle. The band was so named for easy discovery in local record shops. Filed correctly, Abacus records would be the first albums in the first rack of every store.

Intent on finding a central location to maximize their ability to play college gigs around the Southeast, Abacus relocated to Auburn, Alabama. The move coincided with the rise of disco, however, with promoters hiring DJs in lieu of the rock bands that formerly played the bars, clubs, and frat houses around the South. After five months and one show, the band returned to Adel.

With money borrowed from a local bank, Folsom took some of his bandmates to Atlanta’s LeFevre Studios, where they cut enough of his music to release an album under his own name. That debut, Music and Dreams, was self-released on Abacus Records in 1978, a pressing that consisted of 1,000 LPs and 200 eight-tracks. He also pressed 500 singles of “My Stove’s on Fire,” a propulsive yet airy love song that is equal parts Todd Rundgren and Boz Scaggs. That single was backed with “Show Me to the Window,” an introspective ballad that opens with the lyric: “Most of my life I’ve been sad / Thinkin’ of the past and all its dreams.”

Armed with an official release, Folsom drove across South Georgia and North Florida, personally handing records to radio DJs. He packed dozens of copies, sending them to labels like Capricorn—home of the Allmans and Marshall Tucker—and Dark Horse, which was George Harrison’s label. While “My Stove’s on Fire” enjoyed a bit of traction, likely due to its driving not-quite-disco beat and catchy hook, there was little interest outside of Folsom’s corner of the South.

Within a year, he left southern Georgia, following his first wife who was following a job to Jacksonville. His return to Nashville was put on hold. He may have felt a pang of regret at the time, though he doesn’t really remember. Mostly, as with all things, Folsom accepts it as the workings of timing. For him, back then, it just wasn’t time.

Nearing his mid-twenties, with a new baby at home, and hardly endeared to the more Southern-rock leanings of Jacksonville’s scene, with its heavier, beer-drenched sound and less earnest approach to lyricism, Folsom stopped playing in bands, stopped recording, stopped dreaming of someday making a living playing guitar. Still, in the quiet of his home, Folsom continued to write songs, strumming quietly each night for his daughters.

Though he left the dream back in Nashville, unsure when, if ever, he might return, a life filled with music was essential for Robert Lester Folsom. He soon got a job working at a record store, which allowed him to grow his collection for little money, to stay up to date with the vanguard of popular music, and to help his first wife support their growing family. But when the store closed, a victim of the worldwide recession of the early 1980s, Folsom found work as a painter’s helper. Within a year, he started his own residential painting business.

As Folsom became ingrained in his new community, and friends and neighbors found out he played guitar, he was persuaded to join his Methodist church’s praise band. For the next two decades, he focused on his family, his church bands, and his work. In the early 2000s, after his marriage fell apart, Robert Lester Folsom married a woman he met at church. Like him, she had children from a previous marriage. Together, they had a daughter.

With each passing year, Robert Lester Folsom got further away from his dream of being a professional musician, settling into the happy routine of family man, of father, of working-class painter. But soon, and seemingly out of nowhere, that old dream began to realize.

Somewhere around 2009, Folsom was contacted by a man named Douglas Mcgowan. Mcgowan, who had recently started the digital label Yoga Records, read about Music and Dreams in The Acid Archives, a book uncovering hidden gems of psychedelia from the 1960s and ’70s. Intrigued by the short blurb, which likened Robert Lester Folsom to “a second-rate Michael Angelo or a less stringent John Scoggins,” Mcgowan reached out to Folsom, asking if there was any way he could hear the album. Meanwhile, Keith Abrahamsson, co-founder and A&R director of Brooklyn’s Mexican Summer label, had read about Music and Dreams in the über-influential newsletter from New York City’s landmark underground record store, Other Music. Soon after, Abrahamsson visited Mcgowan in Los Angeles, telling him he wanted to release Music and Dreams on vinyl through Mexican Summer. Mcgowan aided the Mexican Summer release as he could, even helping to retrofit the original Abacus Records label with Mexican Summer’s own sigil.

Folsom was excited, though confused. He thought vinyl died long before.

The following year, Folsom—with a backing band of Jacksonville locals, mostly members of his church group—played at the Knitting Factory in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, on a bill for Mexican Summer’s showcase during the once-juggernaut music industry convention CMJ. It was Folsom’s first time in New York City.

As Robert Lester Folsom stood before a crowd who sang his songs back to him, songs he’d written and recorded almost forty years before, songs he hadn’t played live in over three decades, he was overjoyed.

And just as he did in Nashville when he was seventeen, Folsom brought a stack of tapes. This time, he already had an in. This time, he knew his old friend Don Fleming—who grew up across the street from Folsom in Adel and went on to become a luminous name in the world of indie rock, producing records by bands like Sonic Youth, Teenage Fanclub, and Screaming Trees—was in New York, excited to hear what his childhood buddy had been up to. The two had been in and out of touch over the years, with Fleming keeping Folsom in the loop of what was happening in the contemporary indie-rock world. But due to a mixture of friendly jealousy and the idea that his music might not have been squarely in Fleming’s wheelhouse, Folsom never sent his old friend his tapes. However, as Fleming was working as the Executive Director with the Association for Cultural Equity, which focuses on the conservation of the collection of legendary folklorist Alan Lomax, he was eager to help transfer Folsom’s old tapes to digital.

Throughout the digitalization process, Folsom, Fleming, and Abrahamsson began emailing old mixes of the songs to one another, and it was determined there was more than enough material to whittle a cohesive album statement.

In 2014, Abrahamsson released that statement, Ode to a Rainy Day, via his Mexican Summer-backed reissue imprint, Anthology Recordings. Though a bit more refined than his debut, both in craft and execution, and clearly indebted to those British Invasion bands Folsom so loved, Ode to a Rainy Day still held on to the lo-fi bedroom quirk that endeared curious listeners to Music and Dreams. On the back of a handful of good reviews and bubbling word of mouth, the vinyl pressing sold well. In 2022, Anthology released a second collection of Folsom’s recordings from the early seventies, Sunshine Only Sometimes. Though the album finds Folsom veering further into more laid-back AM Gold territory, there’s an underlying sense of spiritual yearning that was often lacking from those contemporaries. It’s almost as if Brian Wilson produced Michael McDonald demos that were co-written by Willie Nelson and George Harrison. Bizarre and beautiful in equal measure.

Nearly fifty years after he started experimenting with reel-to-reel tapes, and a half-century after the staff at Combine told him to come back to Nashville when he was just a bit older, Robert Lester Folsom finally had a music career to speak of.

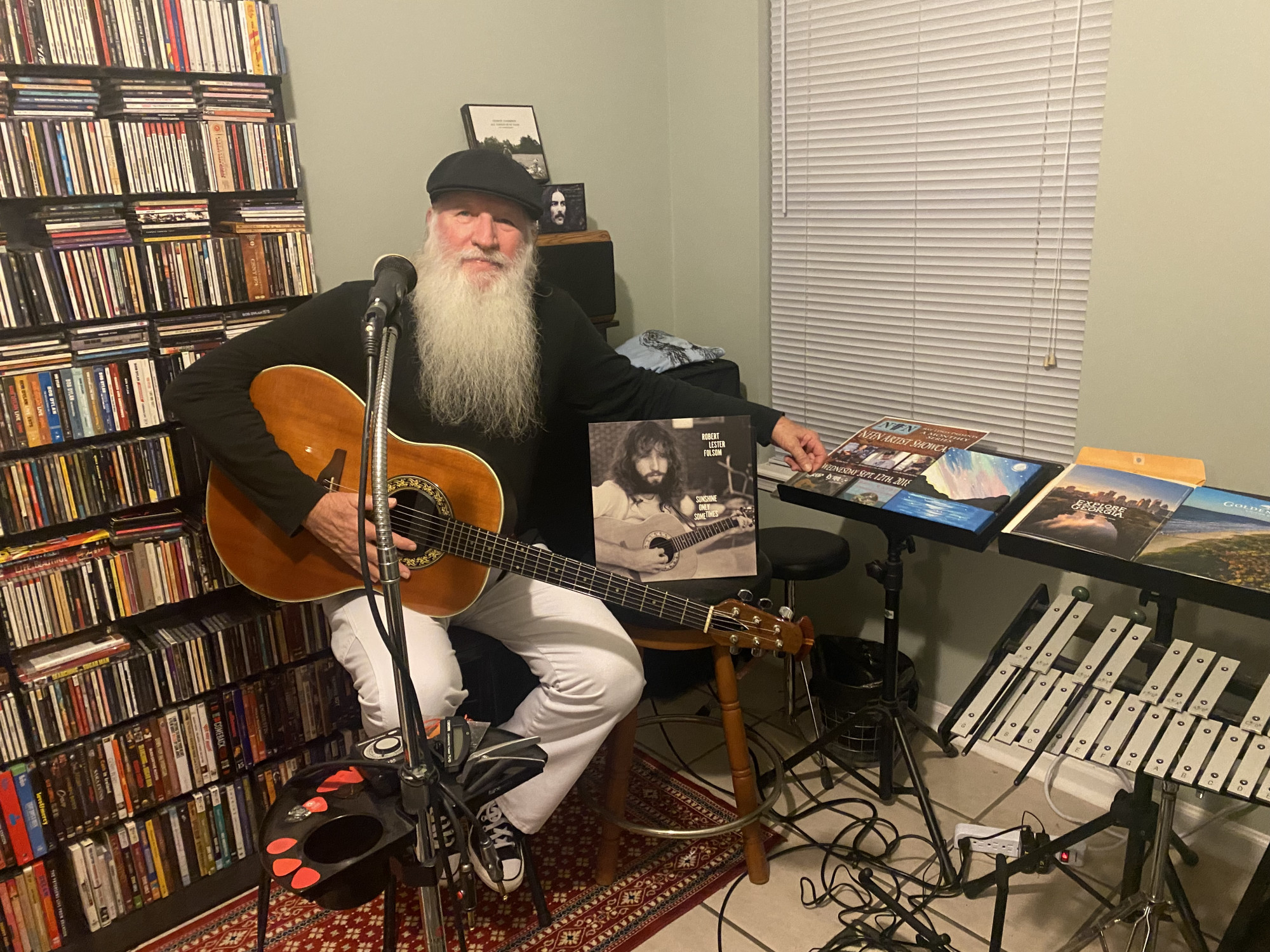

Photograph courtesy of Anthology

Little has changed in Robert Lester Folsom’s day-to-day. He still paints houses, work he finds rewarding after all these years. He still picks up his guitar every night. But now, with a newfound audience and the support of a record label, he’s once again performing his own songs—songs he wrote decades ago, and even some he’s writing now.

Much to Folsom’s delight, the music he made in the 1970s seems to find its biggest audience with millennials. And though it’s impossible to say precisely why, it may be at least partly due to the trickle-down popularity of the Yacht Rock mockumentary web series, which begat a once-tongue-in-cheek-but-then-kind-of-serious resurgence of long-maligned American rock groups like Steely Dan, The Doobie Brothers, and Ambrosia—many of whom share sonic DNA with Robert Lester Folsom.

Folsom’s profile got another kickstart when one of his fans—whom the songwriter had been trading emails with—posted a voicemail Folsom had left him on TikTok with the caption: “I am shitting my pants.” The ensuing comment section is full of people discovering Folsom's music through that TikTok post. Beneath a recording of his song “Heaven on the Beach with You,” you can hear Folsom’s soft voice thanking the fan for listening, expressing his appreciation for the kind words.

Even friends of Robert Lester Folsom’s Gen-Z daughter have come to his recordings, previously knowing Folsom as little more than the guy who played guitar in the church band, the guy who takes daily bike rides as if they’re a religion unto themselves.

And for Folsom, the rides are akin to church. They’re a place to commune with his God. On those rides, Folsom thanks his God for keeping those he loves safe, thanks his God for the beautiful day, thanks his God for the fact that he suddenly has an attentive and eager audience. Robert Lester Folsom thanks his God for the second chance he never saw coming.

Photo courtesy of Robert Lester Folsom

This article originally appeared on OxfordAmerican.org under the title, "Take Two."