THE SOUL OF THINGS GOES

By Win Bassett

Christian Wiman's West Texas

I had recently read Christian Wiman’s latest poetry collection, Once in the West, for the first time when I glanced at my housemate’s copy of The Library of America’s American Sermons one Saturday afternoon while eating lunch. I stopped on Phillips Brooks’s 1890 sermon “The Seriousness of Life” because of the seriousness of its title. Brooks says early in his sermon,

The great mass of people are stunted and starved with superficialness. They never get beneath the crust and skin of the things with which they deal. They never touch the real reasons and meanings of living. They turn and hide their faces, or else run away when those profoundest things present themselves. They will not let God speak with them.

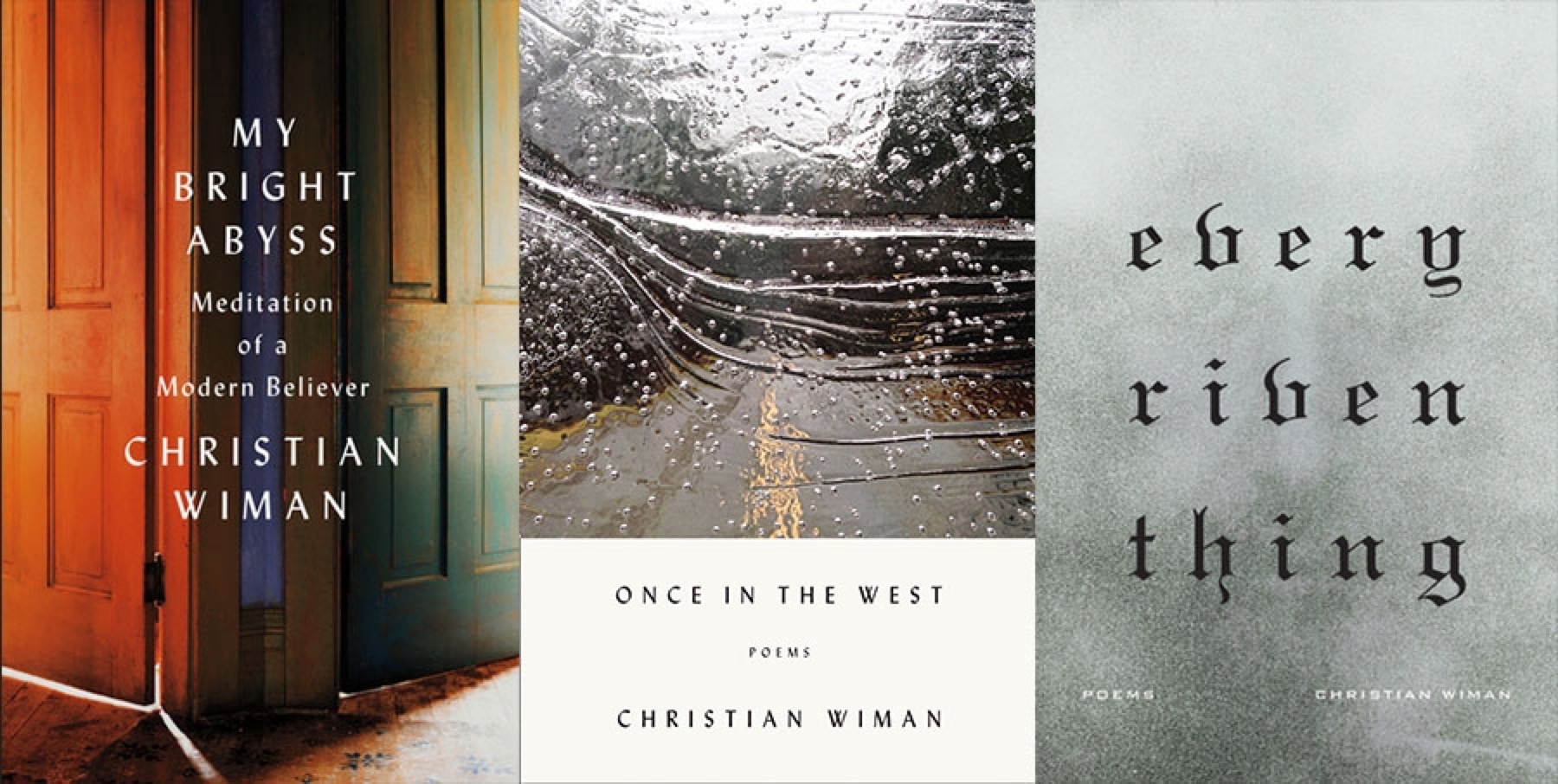

Wiman is an exception to Brooks’s observations. In “Darkcharms,” from his last poetry collection, Every Riven Thing (2010), Wiman’s speaker wrestles with the crust of cancer: “Philosophy of treatment regimens, scripture of obituaries: / heretic, lunatic, I touch my tumor like a charm.” My Bright Abyss, Wiman’s recent memoir of prose and poetry, tells of the pain, affliction, and loneliness suffered to let God speak: “There are definitely times when we must suffer God’s absence, when we are called to enter the dark night of the soul in order to pass into some new understanding of God, some deeper communion with him and with all creation.”

Once in the West is Wiman’s fourth poetry collection, and his first since leaving Poetry magazine, where he was editor for ten years, to teach religion and literature at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music and Yale Divinity School. In the midst of teaching his classes “Poetry and Faith” and “Creative Faith” in the fall semester, Wiman spoke with me about his West Texas upbringing, the influence of “home” on his work, and how the sound of language carries more than his poems. Earlier this week, Once in the West was announced as a finalist for the 2014 National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry.

“Once in the west I rose to witness / the cleverest devastation,” you write in your poem “Razing a Tower.” “Once in the west I lay down dying / to see something other than the dying stars,” you write in “Witness.” The title of your latest collection comes from these lines. Why choose Once in the West for the name of the collection instead of the conventional title poem?

The “West” in this book is both specific and metaphorical. It’s Texas, and it’s timeless. Not timeless as in eternal, though there is that, but timeless as in virtually impossible to fix in time. How and where does faith end in one’s mind, for instance? Or in an entire culture? And would you even call that capacity—that thing that can end—faith? (That’s the question implicit in “Razing a Tower”—which is actually set in Seattle, not Texas; I watched a big building go down when I was twenty-one, and it took me another twenty-five years to realize what I was really seeing.) And what would you call what survives every doubt, prosperity, piety, affliction—amnesia? That’s sort of where “Witness” winds up:

I said I will not bow down again

to the numinous ruins.

I said I will not violate my silence with prayer.

I said Lord, Lord in the speechless way of things

that bear years, and hard weather, and witness.

In your essay “On Being Nowhere,” you describe how you used to answer the question “Where are you from?” with an assortment of answers—San Francisco, Virginia. You told the truth (West Texas) only to yourself in the mirror while getting a haircut. This collection wrestles with describing a relationship to “the west,” but the word “Texas” is nowhere to be found. (You come closest with mentions of “Abilene” and “Trent.”) “Silence is the language of faith,” you wrote in My Bright Abyss. Is silence the language of home?

Decidedly not. Hell-raising ear-twanging all-out-caterwauling pandemonium is the language of “home.” But I see what you’re getting at. There is in all of us—perhaps by “all of us” I simply mean the chaotic clamor of selves that is me—some home we can never quite wake in, some singular self we can never quite be. It occurs to me that that is basically the theme of my second book, Hard Night:

What song, what home,

what calm or one clarity

can I never quite come to,

never quite see:

this field, this sky, this tree.

You once wrote that you’re addicted to absence, or loss:

Indeed, sometimes when I’m home, or traveling through the immense and thriving nowhere of Middle America, it occurs to me that there must be millions of people as addicted to absence as I am, and that our lives, for all their apparent difference, are expressions of a similar loss.

Loss is conspicuous in “Keynote”: “I had a dream of Elks, / antlerless but arousable all the same, // before whom I proclaimed the Void / and its paradoxical intoxicating joy.” The “infinities of fields” also bring a “satisfaction of a landscape / adequate to loss.” Did West Texas instigate this obsession of a recursive Void?

Addicted to loss? Maybe once, long ago. Then I got a good, deep miasmic draught of the real thing and have been nauseated ever since. But the connection between that landscape and loss is, for me, quite real. I wrote a novel once (it died in a drawer) in which a character says that the landscape of West Texas is a terrible landscape for depression, which is a “moist” emotion (she’s a psychiatrist). The desert just crushes that, makes it seem somehow impossible. Grief, though, has its place in such emptiness, that endless sense of something missing—God, for instance. You wonder why there’s so many right-wing wing-nuts grieving God in the deserts of the world (righteous wrath is simply the fumes of unacknowledged grief). I’ve solved the quandary, I tell you.

Along the way of solving the quandary, you wrote in your essay “The Limit” that you began reading poetry shortly after you left Texas for college in Virginia. You loved poetry “most of all for the contained force of its forms, the release of its music, and for the fact that, as far as I could tell, it had absolutely nothing to do with the world I was from.”

You’ve now released a collection of poetry that includes the “five flashlit jackrabbits locked in black,” “old pews, old views / of the cotton fields // north, south / east, west, // foreverness / sifting down like dust,” and a “T-topped Trans-Am.” When did you realize that poetry had something to do with the world you were from?

Early on. The first real poem I ever wrote, at twenty-one, in a mildewed studio apartment in Seattle, was set in the gentle rural poverty and primordial light of my grandmother’s backyard in Colorado City. I never put that poem in a book, as it happens, and it may be that its only existence now is in my head, but still, it occupies an exalted place there. It’s an old story, the return of the prodigal, if only in imagination. There are only old stories, it turns out, which do not obviate our need to suffer and say them in our own language and lives.

Let’s talk more about “the release of its music” quality of poetry. You said recently that you’ve become more of a poet-of-the-ear, more of a Seamus Heaney than a William Carlos Williams, over the span of your time writing poetry. Your poem “Interior”:

To be the wire through which that current burns,

conducting the stone’s slow accretion

like a cry, deciphering sunlight,

to pluck sound from the rings of a tree…

I find myself repeating the hard c’s and r’s of “current burns, / conducting the stone’s slow accretion like a cry.” I also turn over “on the sideboard a lean late husband / hatchets through a half-dozen grainy days” many times. Notwithstanding the onomatopoetic “pluck” sound from a tree above, what, if any, are some of the sounds from your home that form and inform your poems?

My great-grandfather used to get so mad at recalcitrant cows that he would haul off and punch one in the face. I’ve never heard that sound, but it’s as if I have. (Hat tip to Pessoa there.) Once in childhood, I lived in an apartment in which my bedroom window was about fifteen feet from the Dairy Queen drive-up window and lay there night after night tasting the language of Dilly Bar, DQ Dude, and Peanut Butter Blizzard. If I say that little hell hole was heaven, who would believe me? The mystery of poetry is that the sound of language carries the soul of things. The sadness of poetry is that the soul of things goes and goes and goes. “Man is in love and loves what vanishes,” says Yeats. “What more is there to say?”

On the subject of souls, the next stanza in “Interior” is:

More than this I want the silence the ensues,

to believe in nothing but the fact of absence,

striking out again in my hard horizonless country

whose one road releases me like heat as I walk on.

How does your soul reconcile the love of sound with your former addiction to loss, illustrated here with silence?

I think maybe I just answered this, but here’s an addendum. As you know, there is much talk in theological circles about “apophatic” utterance; that is, language that un-says itself, so to speak, language that seeks to reveal God only by negation. “Let me not love Thee if I love Thee not,” says George Herbert. “We pray God to be free of God,” says Meister Eckhart. Those lines above are actually at least fifteen years old. I just never published that poem, though I never knew why until recently: I didn’t understand it. That doesn’t usually bother me—I’ve published lots of things I understand only partially, and some of my favorite poems remain in some way baffling to me—but in this instance, I seemed to need some context for what I was groping toward all those years ago. With this new book I found that.

Another present human influence on your work is Osip Mandelstam, and he floats between the lines of your poem “We Lived.” “Time intensified and time intolerable, sweetness raveling rot,” you wrote in your 2012 translation of his poem “And I was Alive.” In your new poem, you ask the reader to “Imagine a man alive in the long intolerable time / made of nothing but rut and rot.” How does Mandelstam’s language of loss translate into your own?

I don’t speak Russian and did that book with the help of the brilliant poet Ilya Kaminsky and other Russian scholars, so it’s more likely that my language is projecting onto Mandelstam. I did feel a very potent spiritual friction though, as if I’d tapped into something beyond us both. What is most admirable about Mandelstam is the hunger for life and the joy of simply being alive that he gets into his poetry, especially the poetry that is about loss and fear. It’s extraordinary and exemplary and extremely heartening.

Your poem “The Preacher Addresses the Seminarians” evokes an aliveness in a pastor who gives students training to become pastors a homily of reality instead of its “trickle-piss tangent”:

I tell you sometimes mercy means nothing

but release from this homiletic hologram, a little fleshstep

sideways, as it were, setting passion on autopilot (as if it weren’t!)

to gaze out in peace at your peaceless parishioners:

Now that you teach religion and literature at Yale, what would “The Poet Addresses the Seminarians” sound like?

Louder. Maybe all-caps?

Christian Wiman is the author of seven books, including a memoir, My Bright Abyss: Meditation of a Modern Believer (FSG, 2013); Every Riven Thing (FSG, 2010), winner of the Ambassador Book Award in poetry; and Stolen Air: Selected Poems of Osip Mandelstam. From 2003 to 2013, he was the editor of Poetry magazine. He currently teaches religion and literature at the Yale Institute of Sacred Music and Yale Divinity School. He lives in Connecticut.