WHAT SAM PHILLIPS HEARD

By Jonathan Bernstein

Since the early seventies, veteran music journalist (and longtime Oxford American contributor) Peter Guralnick has been one of the foremost authorities on mid-twentieth century American music. From his early collections of artist portraits like Feel Like Going Home and Sweet Soul Music to later titanic biographies of Sam Cooke and Elvis Presley, Guralnick has spent the past fifty years writing about, and celebrating, the history of soul, blues, r&b, country, and rock & roll music with feverish care and devotion.

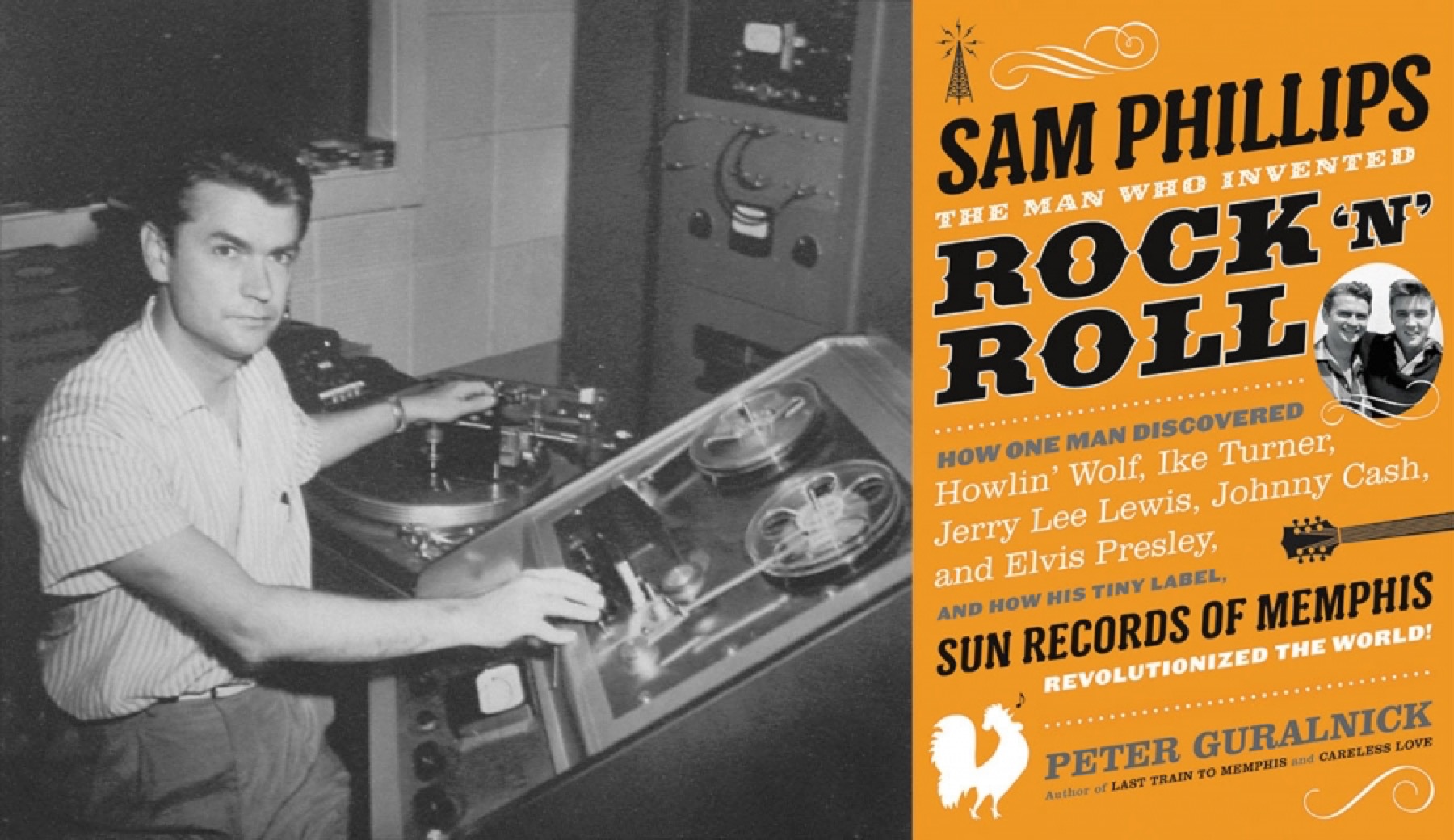

Guralnick’s latest book is a labor of love unlike any other project the writer has taken on. Its full title alone suggests the scope and ambition of the biography that Guralnick knew he wanted to write since he first met his subject thirty-six years ago: Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘N’ Roll. How One Man Discovered Howlin’ Wolf, Ike Turner, Jerry Lee Lewis, Johnny Cash, and Elvis Presley, And How His Tiny Label, Sun Records of Memphis, Revolutionized the World!

The 660-page book, published last week, is an exhaustive, deeply intimate account of Phillips, the founder of Sun Records. Phillips, who died in 2003 at eighty, was an effusive, enigmatic, furiously devoted businessman and record producer whose ambition and creative vision alone places him, for Guralnick, amongst the finest of American artists. In the book’s prologue, Guralnick writes: “Like Walt Whitman, who sought to encompass the full range of the American experience in his poetry; like William Faulkner, who could see past prejudice to individual distinctions; like Mark Twain, who celebrated the freedom of the river and a refusal to be civilized—Sam was driven by a creative vision that left him with no alternative but to persist in his determination to give voice to those who had no voice.”

I recently talked with Guralnick about his new book, the nature of biography, and the endless complexities of Sam Phillips.

You knew Sam Phillips quite well on a personal level. Did that make writing this biography harder? Easier?

Each book has its own challenge. With Sam Phillips, most of all the challenge came in me wanting to take the role to which I was assigned, which was the person writing about him. On the other hand it had a personal element, which I didn’t want to exclude—I simply didn’t want to emphasize myself too much. I wanted also to develop a narrative, a storyline that wasn’t dependent upon “he got this award, he got that award, in 1986 he was elected to the Hall of Fame,” that kind of thing. The way in which his personality both expanded and developed, and the way in which fame impacted him, which was a surprising thing, made his story open up and become more and more of a revelation. We all create stories which fit into compact formats, and the more that I got to know Sam, the more I realized that as much as I might know him, there were unsung depths still to discover, and things which came as real surprises to me.

Was putting yourself in the biography as a character your way of addressing your close relationship to Sam?

That was really what it was. I had had that in mind from the beginning. Sam essentially withdrew from the world in 1960 or 1961; the last forty-three years of his life represented a life that was lived off of the public stage, in the sense that he was no longer making records that had the impact of everybody from B.B. King and Howlin’ Wolf to Elvis and Carl Perkins and Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis. But then when I first met him in ’79, that in a sense marked a turning point in his thinking of how he wanted to present himself, and he became very much a public figure, yet not the same figure that he had been when he was making records: a public figure who was determined to teach lessons about history and democracy. In terms of putting myself into it, I thought it was an inescapable thing not in any way to elevate myself, which was my greatest concern. I wasn’t there for the earlier cataclysmic, earth-shaking events in his life. But what I was there for gave me the opportunity to observe, to interact with him, and in a sense, to offer direct insights and observations about the man who was Sam Phillips. There was no structure in particular to the second half of his life—the offstage part of his life. There was no linear structure, there was no narrative logic—it is an emerging portrait. To me, the one way of presenting that portrait was through my own personal agency.

One of the most fascinating things about this book is learning about Sam Phillips’s evolving relationship with his own legacy, his changing perception of how he wants to be remembered.

Along with many other things, Sam Phillips thought of himself as a teacher and a preacher. He was determined to teach this lesson of history. He believed in the importance of his own story, but he also believed, even more, in the story of the emergence of a more democratic approach, the emergence of a vernacular culture that could be a voice for both poor black and poor white people who had just been neglected by history. His belief in those voices was something that he was resolutely committed to.

This book presents Phillips as a heroic, larger-than-life figure, but I was struck by how tragic his life was in many regards. Do you think he ever got over being abandoned by artists like Johnny Cash and Jerry Lee Lewis?

I think it marked him and he spoke of it. He certainly got over it in a personal sense—he had nothing but admiration for Johnny Cash, but it continued to gnaw at him. More significantly, the kind of story that I’m trying to tell, whether it’s about Sam Cooke or Sam Phillips, is a story that combines comedy and tragedy, a story that doesn’t try to come to any pat conclusions: life is just one great glorious upswing. I wanted to tell a complex human story, and I can’t imagine a complex human story that didn’t include the seeds of tragedy as well as the seeds of triumph and everything else. Ultimately—and this is maybe the thing which has much more to do with a creative nature than it does with Sam in particular—it’s the solitariness of someone whose mission was to communicate with the world. Sam Cooke, who couldn’t have been a warmer and more charismatic personality, felt that same sense. There’s no question that I think that exists in many dimensions of Sam Phillips’s story. It would be doing a disservice to him to try to create some kind of perfect story to gloss over the imperfections. As Sam said, “I hate perfection. Who would ever want to achieve perfection?”

Many of us might like to achieve a greater perfection in terms of our own personal lives, but I think for somebody who strives in the way Sam Phillips did, in the way Sam Cooke did, or Elvis or Howlin’ Wolf—these were all people who felt things very deeply, and who were obsessed by worries and doubt. And as much as they loved the people around them, they didn’t create a perfect world for the people around them either. That’s one of the reasons Sam identified so much with Charlie Rich, and weirdly enough, I think it’s one of the reasons he identified so much with Jerry Lee Lewis, who was the ultimate extrovert. As Solomon Burke once said to me, he says, “But what I want to know is who is Pete the writer when he’s alone in his hotel room at night?” Jerry Lee Lewis, this great extrovert personality, was also a person of great sensitivity. It’s funny, it’s an across the board kind of thing—so I agree with you, but I agree with you in a larger sense.

One thing I didn’t realize about Sam’s story was how intentional and abrupt his shift was from exclusively recording black blues and r&b artists to exclusively seeking out white artists. What do you make of that?

One of the things Sam always said to me was that Howlin’ Wolf could have been as big as Elvis Presley. He could have had just as wide an audience. Now this is something I never could quite see, despite the fact that in my mind there’s nobody higher than Howlin’ Wolf, but what I didn’t realize at first was that from the time that Sam first went on the record in 1951, he was talking in the same way. When “Rocket 88” hit, Sam was saying that this was something that could be a hit across the board; it could be just as big for white audiences as for black audiences. And he believed that from the bottom of his soul. Another thing that surprised me was when I realized that “Rocket 88” sold over 100,000 copies, that was a huge hit. But what Sam discovered was that as big as “Rocket 88” got, as big as Howlin’ Wolf was with “Moanin’ in the Moonlight,” he believed—as Ray Charles said, he believed to his soul—that these records could and would cross over. But although they must have had a fair number of white sales, they didn’t cross over and they reached a ceiling, he hit the ceiling.

So it was not only a matter of staying in business, although that was certainly a huge part of it, it was also a matter of his finally coming to the conclusion that the only way he was going to sell this music to a large, mixed audience—the only way he was going to cross over into the mainstream with the music he believed in so much—was by recording a “white man with the sound and the feel of a negro,” as he said. In early interviews, he made clear that this was what he finally realized he would have to do to cross the music over, to get a large, mainstream, which is fundamentally a white audience, to hear the music. To hear in the music what he heard.

As someone who has spent his whole life devoted to studying and celebrating the complexities of music from the fifties and sixties, how do you react when you hear people say things like, “Elvis ripped off black rhythm & blues”?

I don’t take it personally. I’ve certainly run into that argument with Elvis, in particular. I think that in a sense it’s a misreading of popular culture, in that every popular artist or songwriter since the phonograph was invented has sought the largest possible audience. Little Richard said “Thank god for Elvis Presley” because Elvis’s success brought Richard not only more attention but more income than he said that he could have imagined. There might be some irony in that, but not much. I think it’s a reduction when you start talking about somebody ripping off this music. When you start talking about cultural theft then you have to start defining it much more closely. You say, Well alright, the minority culture can never rip off the majoritarian culture, and you sort of end up with so many qualifications on it, and the real question is: are people getting their just rewards? And the ultimate answer is they almost never are, and the ultimate reason for that is a capitalist system which is never going to give explanations—it’s going to charge as much as the market will bear, and anybody who doesn’t understand the vocabulary of a recording contract is going to be taken advantage of.

What do you make of Sam’s musical relationship to women? On one hand, he pioneered an all-female radio station, but he also had almost no interest in ever trying to record female artists at Sun.

My only guess would be it was the same as it was for gospel music: he didn’t see a way of selling it. To some extent, Elvis’s success established the imprint for all the future success. All these people found their way to Sam’s studio, whether it was Sonny Burgess or Roy Orbison or Warren Smith—they all came because of Elvis. So you ended up with this string of hits coming out of the studio where, to some extent, the pattern had already been set by Elvis. There were nowhere near as many women singers who went out as solo artists at that time. It wasn’t as commonplace; you didn’t have success of women in the marketplace that men had established. But I think it may be that Sam never felt as comfortable. I don’t know that he ever found out, but for whatever reason it was not something that he pursued.

Sam Phillips: The Man Who Invented Rock ‘N’ Roll is out now.

In the Oxford American’s Georgia Music Issue, on newsstands December 10, Jonathan Bernstein profiles Dave Prater of Sam & Dave, and Peter Guralnick writes about Blind Willie McTell, James Brown, and his own discovery of the blues.