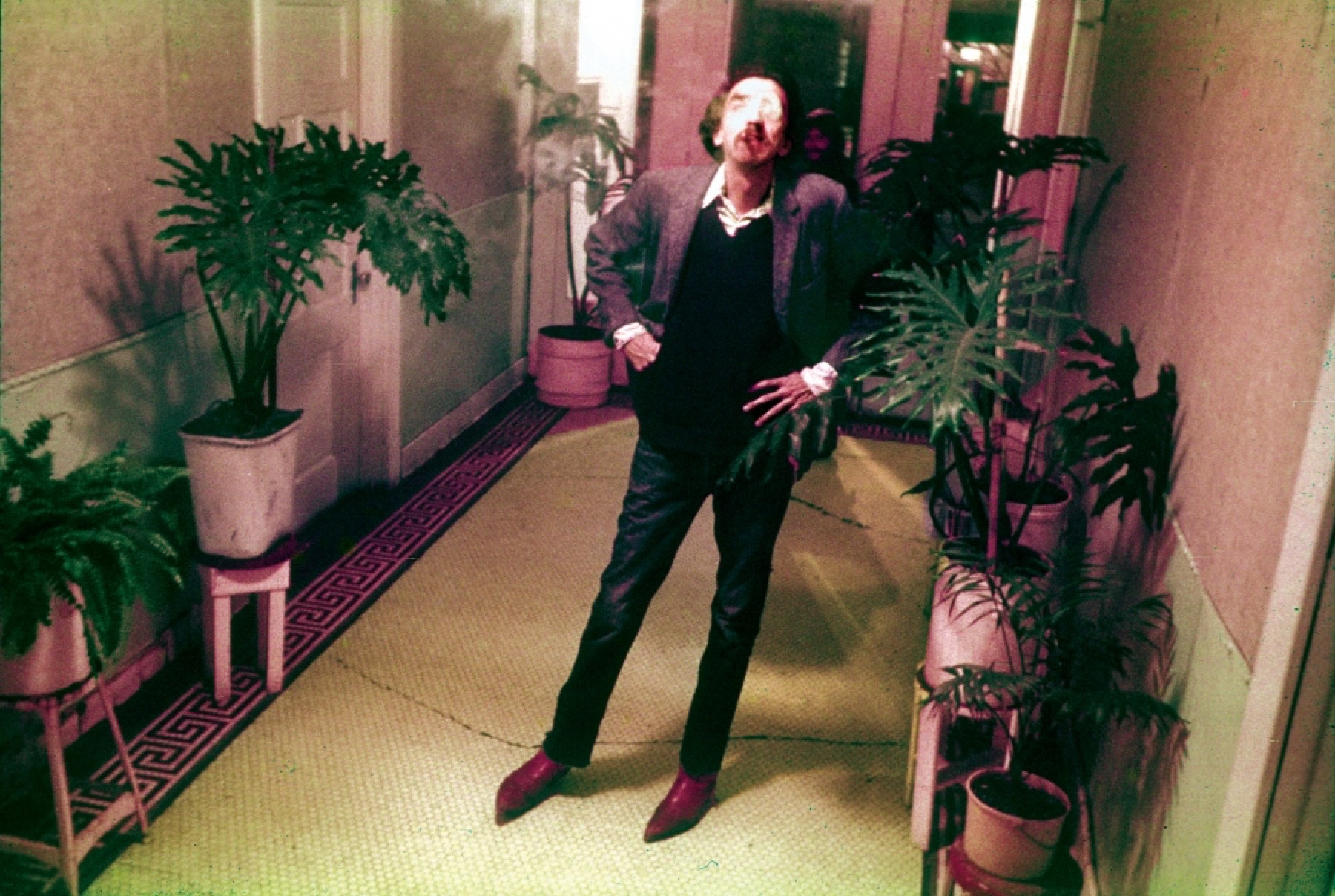

Skinny Dennis Sanchez, Nashville, Tennessee, early 1974

KEEPERS

By Rien Fertel

From Houston to Long Beach to Old Hickory Lake

An excerpt from “The Whole Damn Story,” an eighty-page book included with the Heartworn Highways 40th Anniversary Edition Box Set, available on Record Store Day, April 16, 2016. Reprinted by permission of the author and Light in the Attic Records.

Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt met during what Clark later called “the great folk scare.” Houston in the early 1960s had a folk community that paralleled those in Cambridge, Minneapolis, or Los Angeles—only smaller and with better bluesmen. The musicologist John Lomax ran the Texas Folklore Society and would arrange for veterans like Lightnin’ Hopkins and Mance Lipscomb to play concerts at the Jester Lounge on Westheimer, where they would turn Kingston Trio fans onto something tougher. As Lomax’s son, John Lomax III, put it, “Lightnin’ was as electric as you could get with an acoustic.” Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt were among the room’s transfixed teenagers.

The son of an attorney, Clark grew up in a household filled more with poetry than music. After meals, the family played Scrabble and read aloud Robert Frost, Robert Service, and Stephen Vincent Benét. The boy’s earliest musical instruction came via a clerk who worked for his father’s firm in the Gulf Coast town of Rockport, three hours south of Houston. She taught Guy his first songs in Spanish. Soon, he was dismantling flamenco guitars for fun. As a teenager, Clark spent summers in the West Texas oil town of Monahans, where his father’s mother ran a boarding house that attracted flyboys and roughnecks passing through the desert. She was fond of a tough, aged wildcatter named Elsie Jackson Prigg. Born in 1887, Jack Prigg had worked for Gulf Oil since the 1910s. He told Guy stories of drilling the first leases in Venezuela and Kuwait in the twenties and explained the rivalries between the cable tool drillers, called “ropechokers” or “jarheads,” and rotary drillers, who were “swivelnecks” or “mudhogs.” Clark accompanied Prigg on visits to the rigs in West Texas, where he watched a gusher blow the racking board off the top of a derrick. Prigg gave him his first taste of beer and let him drive his ’38 Packard Coupe on trips back from company picnics in Odessa. At night, the old man would borrow a guitar from the local pawn, and they’d sit around his grandmother’s kitchen table at the hotel as Prigg would tearfully ask a teenage Clark to play “Red River Valley.”

In high school, Clark worked shrimp boats around Rockport, messed with guitars on the side, and eventually bounced around to a few nearby colleges. After a stint in the Peace Corps, he landed at the Jester, where he fell in with a traditional folk trio, playing “Handsome Molly,” “Cotton Mill Girls,” and whaling ballads to the tidy folkies. There, he first met Van Zandt, the thin but handsome son of a Texas society family. Van Zandt’s parents had pulled him out of college in Colorado for huffing airplane glue, which dampened the family’s hopes that Townes might one day grow up to govern Texas. That was before he saw Lightnin’ Hopkins, who had a gold tooth, made up songs on the spot, and could put away a fifth of whisky without missing a note.

In Houston, Townes palled around with Jerry Jeff Walker, a traveling folksinger from New York. As Jerry Jeff’s understudy, Townes amassed a repertoire of joke songs and talking blues—“geared toward the beer crowd,” he later said. His first truly original work was called “Waiting ‘Round To Die.” Townes was the first kid Clark met who wrote seriously—the first person his age to show what was possible. Then, he’d turn around and do a pratfall. “Townes thought he was better than Chevy Chase at pratfalls,” Guy said later. Though three years younger, Van Zandt was Clark’s hero.

They became a pair, carousing around the Jester and, later, Sand Mountain, an alcohol-free folk club opened by proprietress Ma Carrick, who hoped to capitalize on the folk fad that had consumed her son’s high school friends. She refused to pay for a liquor license but served coffee and soft drinks for a dollar and let folksingers in need crash in a garage apartment adjacent to the club. Jerry Jeff and Townes both lived there for a while and rigged a pulley to surreptitiously haul up bottles of cheap booze from the back alley.

Before either turned twenty-five, Guy and Townes each got married and had a son. It was what was done, the least of what their families expected of them. While Guy took a job as an art director at KHOU-TV, the local CBS affiliate, Townes got a ticket to Nashville to make a record on the invitation of Mickey Newbury. All of the Houston folksingers looked up to Newbury. He had come through the Jester a class ahead of them. A former doo-wop singer from the roughest section of North Houston, Newbury had started to craft country folk songs inspired by Bob Dylan and the Beatles. In 1965, he’d won a publishing deal with Acuff-Rose, and Nashville stars started getting scores with his songs. He was the first Texas hippie-cowboy accepted by Nashville’s old guard. Kris Kristofferson idolized Newbury, but Mickey idolized Townes. “Townes is somebody who looks a little like Hank Williams, even writes like Hank Williams probably would have written,” said Newbury, “but I tell ya, I think Townes is better. I consider him in the same category as Dylan and McCartney . . . his songs are really involved, but at the same time, they’re deceptively simple. That’s what makes ’em good.”

Struggling to find his way, Guy started a guitar repair shop with a friend and even spent a summer in San Francisco after he and his wife split. It didn’t take. He was always reaching for the independence that came naturally to Townes, who seemed to move as freely through life as he did within the language of his songs.

Every city with a college had a coffeehouse. When Townes was around, he and Guy would pick up one-nighters at campuses and folk clubs within a day’s drive of Houston. In Austin, the Chequered Flag; in Beaumont, the Halfway Coffee House; in Tulsa, the Dust Bowl. After a stop at the Sword and Stone Coffeehouse in Oklahoma City, they ended up in the apartment of a Dylan devotee named Bunny Talley and her older sister, Susanna, who taught art at the Oklahoma Science and Arts Foundation, which had been founded with contributions from her mother’s family. Two of ten siblings, the sisters had grown up in Atlanta, Texas, south of Texarkana, and moved to Oklahoma City when their dad’s business took off. Knowing Bunny and Guy had a thing, Susanna sized up the two Houston longhairs—Guy with the dark brow and square chin, and Townes, gallant and goofy. They were skinny as rails. She offered them a vitamin pill. Guy studied the easel she was working on in the middle of the room. When he asked what she planned to do about the foreground, she grappled for an answer. “You know what to do,” Guy said. Then Bunny led the rail-thin longhairs away to a party, and they subsequently blew town. Townes’s New York management had booked him a showcase at Carnegie Hall with other artists on the fledgling hippie label, Poppy.

In May, 1970, when Let It Be was new and everyone was mourning the Beatles, Jack Prigg died, age eighty-three. Stricken with grief, Guy was on his way back to Monahans for the funeral when he got a call from Susanna Talley. Bunny had killed herself with a gunshot to the head. Susanna was inconsolable. Guy said he’d stop in Oklahoma City on his way back from Monahans. They held hands at Bunny’s memorial. From then on, they were together.

That July fourth, Susanna moved in with Guy in Houston, where he was living in a communal flophouse in Montrose, the heart of Houston’s counter-culture. Everyone was taking hallucinogens. Longhairs dangled from windows. All the young songwriters and pickers hung out at the Old Quarter, a converted speakeasy on the outskirts of downtown Houston operated by Dale Soffar and Rex Bell, two eccentric, Jewish folksingers stranded in cowboy country. “It was run more as a front for some marijuana dealers than as a club,” said John Lomax III, a friend to both owners. The schedule was loose. Guy or Townes or Jerry Jeff could play whenever they felt like it. Once in a while, a touring band like the Allman Brothers might end up there, as much for the company of the dealers as the music. The Old Quarter served liquor, and joints were enjoyed on the privacy of the roof. Nobody minded if you went behind the bar to pour your own beer. Ma Carrick finally caved and bought a liquor license, but by that point, Sand Mountain didn’t stand a chance.

At the flophouse, Susanna tried to paint. She started fiddling with a life-size portrait of the denim work shirt that Guy liked to wear. Mostly, she was miserable, an uprooted debutante with a degree in psychology and philosophy, left to grieve for her sister among the reckless acid pranksters of Houston. Between recording dates in Nashville and his neverending touring cycle, Townes would suddenly appear, the only soul who seemed to recognize the sadness invisible to the rest of the world. One night at the house, he placed his arms on her shoulders and said, “If Guy loves you, I love you.” Susanna later said it was the first time she felt as if somebody meant it. “It was so touching to me, and for the first time, I felt at home.”

By early 1971, Guy was almost thirty. He worked at the TV station and played the Old Quarter on weekends. One night, a couple of scouts from Elektra stopped by in search of new talent, but the most they offered was the invitation to look them up if he was ever in Los Angeles. Spurred by Townes, Clark wrote and wrote, searching for the keepers—those songs so potent they could be played in front of any audience—but threw away everything he finished. He’d come home beaten in the evenings. One night, Susanna asked him if this is what he wanted to be doing in life. “No,” he said. “I want to play music for a living.”

“Well,” she said, “you’re an artist at a television station. No producer is going to come knocking on your door in hippie Houston. If you really want to do music, then quit your job, and let’s go to someplace that you think they’ll listen.” He was stunned. It never occurred to him that a woman would allow, let alone encourage, him to abandon steady employment.

He remembered what the guys from Elektra had told him, so they packed his VW bus and went to Los Angeles. Guy found work at Original Musical Instruments, a dobro factory in the port city of Long Beach, thirty miles south of the music industry. He and Susanna rented a back house on Magnolia, a short drive across L.A.’s concrete riverbed from OMI, with a prime view of the oil derricks atop Signal Hill. Soon after they moved in, Susanna finished the painting of the denim shirt, and Guy finished “Desperados Waiting for a Train,” his tribute to Jack Prigg—his first keeper.

Susanna and Guy Clark with Townes Van Zandt at John Lomax III's house, Nashville, Tennessee, early 1974

Susanna and Guy Clark with Townes Van Zandt at John Lomax III's house, Nashville, Tennessee, early 1974

Early in high school, Dennis Sanchez hit six-foot-seven, a moving surrealist sculpture with olive skin, Roman nose, and a bouquet of brown curls. Everything about him was spiderlike. Long legs, arms, nose, fingers, face. He had trouble finding jeans that were long enough to touch his ankles and small enough to stay on his slim waist. He was famous throughout Long Beach and Seal Beach, befriending people of every age and type. He radiated a warmth and kindness and openness that invited new company everywhere he stepped. The parents of his friends were always saying, “Why can’t you be more like Sanch?”

Dennis was always the first to take a dare, to wear the lampshade, to drink everything on the table. Only his closest friends knew about his condition. As a kid, he’d been diagnosed with Marfan syndrome, the degenerative disease that afflicted Abraham Lincoln. (“Believe me, that’s the only thing Dennis and Abe had in common,” Townes later quipped.) His weak heart presented a severe risk, even in youth. The doctors told him if he stayed away from drugs and alcohol and refrained from all exertion, it might be possible to extend his lifespan to forty. “From then on,” said his best friend, John Penn, “he did everything to the maximum.”

As high schoolers, Penn and Sanchez and Steve Shield, a friend of Dennis’s from St. Anthony’s Catholic School, built a dragster and started entering races at Lions Drag Strip, Long Beach’s storied track. They were the only grease monkeys who loved folk music. Seeing Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee at the Golden Bear in Huntington Beach changed their lives. The teenagers would forfeit the early heats at Lions and pull their instruments from Dennis’s station wagon. John played guitar, Shield plucked banjo, and Dennis dwarfed his washtub bass. Their fellow racers had a good time booing them.

Penn and Shield were drafted in 1966. Dennis failed the physical and stayed home in Long Beach. With Penn gone, he gravitated to Strawberry Fields, a head shop and bookstore that became the nexus of Seal Beach’s thriving counterculture. He picked up landscaping jobs around town with his new friend, Michael Harris, another Strawberry Fields regular. The Mexican gardeners pointed at Dennis and called him “manguera,” meaning “garden hose.”

When Penn got back from Vietnam, his childhood pals all had long hair. Getting high and playing music had supplanted racing as the pastimes of choice. A few miles north in Los Angeles, acid rock ruled, but in Long Beach, it was all folk and bluegrass. Gerald McCabe’s guitar shop was the hub of the city. The Dillards’ arrival in ’64 had a bigger effect on the locals than Bob Dylan’s appearance at Long Beach High School the same year. The Nitty Gritty Dirt Band became the big local band, and soon, string bands and banjo-driven mischief were happening everywhere. Dennis loved playing the pickup bass. He freewheeled happily through the local coffeehouses and pizza parlors, augmenting trios and assorted string bands. A bass man was always in demand.

A bungalow at 239 Newport Avenue became a crash pad for Dennis, Michael Harris, and an ever-shifting assortment of musicians, artists, and pot smokers. Because Harris and Sanchez were so social, newcomers were often drawn into its orbit. Jim Szalapski had come to Long Beach from his hometown of St. Paul with a degree in commercial art and a minor in photography. An expert airbrusher, he’d paid his way through the University of Minnesota by working the car show circuit, where he hawked custom T-shirts to hot-rodders. In Long Beach, he refocused on film and photography. John Penn remembered him carrying an expensive Leica around like an oversized necklace. “Days might go by,” said Penn, “and then every so often, he’d snap a picture when he saw the right thing.” As he worked various jobs as a graphic designer for advertisement firms, Jim made films and photographs of the happenings at 239 Newport before moving to New York in 1969 to pursue a full-time career in film. To avoid the draft, Michael Harris fled that summer to New York, where he moved into Szalapski’s top-floor loft in SoHo.

Guy Clark got to Long Beach just after Szalapski left, and he and Susanna would stop by the bungalow at 239 Newport to play music. On one occasion, Dennis took Steve Shield on a visit to meet Clark at his house on Magnolia. Susanna welcomed them with tea and cookies. She was easily one of the most beautiful people Steve had ever seen. Guy played them his new songs and told stories about working for the Dopyera brothers at OMI. “Weird, old, cranky farts,” Guy later said. Their father had produced basses and cellos back in Czechoslovakia, but the sons originated the idea of amplifying a guitar with a resonating cone, as on a Victrola. Rudy kept his own little workshop up on a loft at OMI, hammering out bell brass F-5 mandolins, while Ed, the younger brother, ran the business. Neither one of them played guitar except for two chords to check the sound of something they made. They were machinists and inventors more than musicians. Guy liked to say the dobros he made there were more like toasters than guitars.

The job suited Guy because any time he had an appointment with a publisher, the Dopyeras would let him skip a shift. He’d drive his VW bus up to Los Angeles to play for A&R men in corporate offices. One by one, they passed and sent him packing. In the meantime, Dennis invited him to sit in with the City Limits String Band, a bluegrass outfit that featured a local couple, Tim and Marilyn Smith, on banjo and guitar. They’d play all the little folk clubs along the coast: Sid’s Blue Beet, The Insomniac Coffeehouse, The Prison of Socrates, The Merry Monk. Susanna was their lone loyal groupie. One night, they trekked all the way down to Mission Beach to play the Heritage Coffeehouse, where a young San Diegan folksinger named Tom Waits worked the door. On the long drive back at 3 AM, Guy found himself sprawled in the rear of Dennis’s station wagon with Susanna. Out of pure exhaustion, he said to no one in particular, “If I could just get off of this L.A. freeway without getting killed or caught.” So as not to forget, he wrote it down in Susanna’s eyebrow pencil on an empty burger bag.

With four albums under his belt for Poppy, Townes came to Los Angeles in the summer of 1971 to record a new LP in the company of his girlfriend, Leslie Jo Richards, one of a coterie of beautiful young Houstonians who idolized him. When he wasn’t busy, he’d drive south to Long Beach and crash with Guy and Susanna. They introduced Townes to Dennis. In youth, Sanchez had been handed a terminal diagnosis, while Van Zandt’s early memories had been erased by a series of disciplinary inpatient shock treatments. Each had been forced to accept life as a fragile and frequently tragic proposition, to which each responded with redoubled hunger to live solely for the fun of the present moment. Upon meeting, the pair became instant brothers in mischief, always gambling and goofing and making up music, each egging the other on.

To escape the city’s summer heat, Guy and Susanna and Townes took a road trip into the forested San Gabriel Mountains in the VW bus. Townes built them a campfire in the dark, and they traded songs all night. On the way back down, Townes improvised a song on the spot: “No deal, you can’t sell that stuff to me / No deal, I’m going back to Tennessee. . .” They were a triangle of closeness. Guy and Susanna were married partners. Guy and Townes were best friends. Susanna and Townes were soulmates.

In early August, as Townes put the finishing touches on the album that would become High, Low, And In Between, Leslie Jo Richards was abducted while hitchhiking back to Houston from San Diego. She crawled onto a stranger’s doorstep in Leucadia Beach and begged for help as she bled to death from the stab wounds. Townes called Guy and Susanna. For once, he refused to come to Long Beach. He asked them to come north to Los Angeles so he could tell them in person. They found him inconsolable. The trio grieved, three united by losses.

That fall, Townes retreated to the bleak side of Houston. He overdosed on heroin at his mother’s house. At the hospital, they managed to revive him, but they had to knock out his front teeth to get a breathing tube down his throat. Afterwards, he got a gold tooth installed, just like Lightnin’s.

Meanwhile, after playing for an RCA rep in Los Angeles, Guy was finally offered the publishing contract he’d been chasing. For fifty bucks a week, Sunbury-Dunbar, RCA’s publishing division, would own a piece of anything he wrote. He was told he could live in L.A., New York, or Nashville. He and Susanna had seen enough of the big city. Guy knew he could stay with Mickey Newbury in Nashville. RCA told him to bring a tape with him. Before he left, Guy recorded a six-song demo in the living room of John Penn’s house in Seal Beach, with Dennis thrumming his bass in the background. The songs were “That Old Time Feeling,” “Step Inside This House,” “Waitress, Waitress,” “Texas Goodbyes,” “Texas Bound,” and “The Old Mother’s Locket Trick.” He had found his voice in images of the Texas he’d left behind, but the first song he finished when he got to Nashville was a goodbye to Los Angeles:

Now here’s to you old Skinny Dennis

The only one I think I will miss

I can hear those bass notes ringin’

Sweet and low like a gift you’re bringin’

So play it for me one more time now

You got to give it all you can now

I believe every word you’re sayin’

Just keep on, keep on playin’

If I could just get off of this L.A. Freeway

Without getting killed or caught

Down the road in a cloud of smoke

To some land that I ain’t bought, bought, bought . . .

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter to read more.