Think Twice

Remembering Bob Dylan’s forgotten album

By Elijah Wald

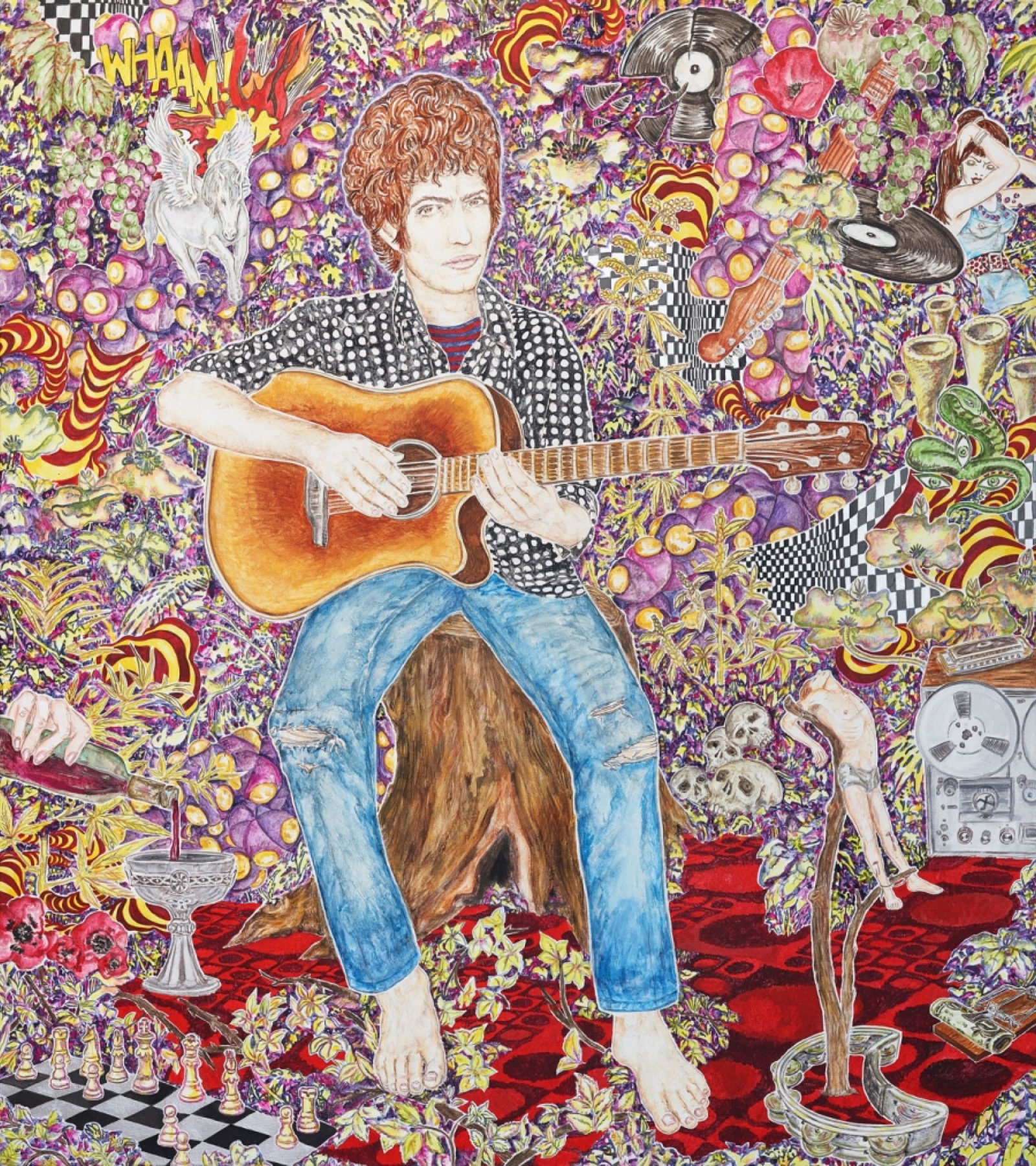

"Bob Dylan" (2011), by Abetz & Drescher. Image courtesy of the artists and Magic Beans Gallery, Berlin, http://magicbeans.gallery

I’ve spent a lot of time recently listening to Bob Dylan’s second album. Not Freewheelin’, the LP with him and Suze Rotolo on the cover and “Blowin’ in the Wind” in the grooves. That’s the one we know, because a couple of songs off it were picked up by the Chad Mitchell Trio and Peter, Paul and Mary—and then by everyone from Bobby Darin to Marlene Dietrich—and Dylan was hailed as a poet and the voice of a generation. But before that happened, he’d spent a year working on a follow-up to his first LP that displayed very different skills and inclinations.

My second Dylan album is the one with a loping piano version of Robert Johnson’s “Milkcow’s Calf Blues,” punctuated with wild falsetto whoops. The one with a propulsive “Baby, Please Don’t Go,” fresh in his mind after his recent session playing harmonica for Big Joe Williams. The one with “Wichita,” tracing his mythical hobo travels:

That record was never commercially released, but the studio tracks have survived and been traded among hardcore fans, and they show an alternate Dylan: not the folky bard of the standard biographies, but the hippest young blues singer in Greenwich Village.

For fifty years, we’ve been told that Dylan arrived in New York singing Woody Guthrie’s Dust Bowl ballads, began writing his own protest songs in Guthrie’s style, then grafted that style with the modernist poetics of the French Symbolists and the American Beats. That story made perfect sense to all of us who discovered Dylan after Freewheelin’ and The Times They Are A-Changin’—which is to say, almost everyone outside a small band of early fans in the Village. But to a great extent it is revisionist history, ignoring the way his first album was presented and how those fans described him before the folk-poet thing took off.

Take his first newspaper review: in September 1961, Dylan played two weeks at Gerde’s Folk City with the Greenbriar Boys, and Robert Shelton gave him a rave in the New York Times. A quarter century later, Shelton would recall that Dylan sang in a “rusty voice, suggesting Guthrie’s old recordings,” with an overlay of Dave Van Ronk and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. But back in 1961 Shelton didn’t mention Guthrie; he wrote that Dylan’s voice had “the rude beauty of a Southern field hand musing in melody on his porch. . . . He may mumble the text of ‘House of the Rising Sun’ in a scarcely understandable growl or sob, or clearly enunciate the poetic poignancy of a Blind Lemon Jefferson blues.”

When Dylan’s eponymous first album appeared, in March of 1962, the liner notes—again by Shelton, using the pseudonym Stacey Williams—described him as “a young Woody Guthrie” but immediately followed with “or a composite of some of the best country blues singers.” That portrayal was fleshed out with mentions of Sonny Terry and Little Walter Jacobs as Dylan’s harmonica models, his week at Folk City opening for John Lee Hooker, a meeting with Mance Lipscomb, and his debt to the recordings of Big Joe Williams and Rabbit Brown, along with Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers, Jelly Roll Morton, Carl Perkins, and early Elvis Presley. (Individual song notes added Jesse Fuller, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Roy Acuff, and the Everly Brothers.) A Village Voice reviewer praised that album’s comic “Talkin’ New York,” but ignored Dylan’s only other composition, the nostalgic “Song to Woody.” Instead, the writer hailed him as a powerful musician and performer, “a growling, grumbling force backed up by flailing guitar which can drive you wild,” and called the disc an “explosive country-blues debut.”

That review startled me when I first read it a couple of years ago, because I had always heard Dylan’s early style described in very different terms. By 1963, Shelton was setting a pattern that has been followed ever since, writing: “His voice is small and homely, rough but ready to serve the purpose of displaying his songs.” And yet, in retrospect, the Voice’s description seems uncannily prescient, foreshadowing the Dylan who electrified Newport with the Butterfield Blues Band in 1965 and cut Highway 61 Revisited—or the Dylan on 2001’s Love and Theft and at his best shows today.

I missed the continuity between Dylan’s early blues and his later rock excursions because, like almost everyone in the 1960s, I became aware of him through other performers: as the composer of Peter, Paul and Mary’s lilting protest anthems, the Guthriesque ballads Pete Seeger performed at Carnegie Hall, and the Byrds’ mellow take on “Mr. Tambourine Man.” By the time I discovered his own, rawer versions of the songs, I associated him with those performers and continued to see him through that prism: as a brilliant, difficult artist whose work was a gritty cousin to the pretty pop-folk style.

In terms of broad cultural impact, it makes sense to see Dylan primarily as a groundbreaking lyricist, a modern bard who has inspired generations of singer-songwriters. That is the Dylan who just won the Nobel Prize in Literature, and whose influence permeates every strain of popular music. But the focus on Dylan’s writing makes it easy to forget that he was signed by Columbia Records and hailed by early reviewers as a compelling musician and singer, and as a rough blues artist rather than a sensitive balladeer. When he went electric it was a return to form, and the title of his breakthrough hit, “Like a Rolling Stone,” neatly signaled his kinship with those other young blues fans who were tearing up the charts that year—not coincidentally with a series of Dylan pastiches: “(I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction” followed by “Get Off of My Cloud” and “19th Nervous Breakdown.” (The British r&b scene had embraced Dylan as a blues artist from the start, the Animals copping “Baby, Let Me Follow You Down” and “House of the Rising Sun” off his first LP.)

By 1963, it made sense to market Dylan as a folk poet. But before adopting that strategy Columbia actually tried the electric route: Dylan’s first single, released on the cusp of that year, was “Mixed-Up Confusion,” a rockabilly raver recorded alongside a hot take of Big Boy Crudup’s “That’s All Right” (with Bruce Langhorne playing the same guitar riff he later used on “Maggie’s Farm”) and a souped-up rewrite of an old section-gang song, “Rocks and Gravel.” The single went nowhere, but it is easy to see why Columbia gave it a shot: Dylan didn’t sound like a smooth-voiced pop-folky, and proudly affirmed his roots in rock & roll. His rambling hobo stories included claims of backing Gene Vincent and Bobby Vee, and the references to Presley, Perkins, and the Everlys on his first album were backed up by the “Wake Up, Little Susie” riff he tacked on to Tommy McClennan’s “New Highway No. 51.”

Many of Dylan’s friends and mentors on the folk scene dismissed rock & roll as commercial pap, but he saw it in different terms. As a Minnesota teenager he had discovered Gatemouth Page’s nighttime r&b broadcasts from the wilds of Louisiana, and a high school pal taped him playing high-powered piano and arguing that Elvis was just imitating Little Richard and Clyde McPhatter. As his tastes expanded over the next few years, he always maintained a deep affinity with black music. That was one of the things that attracted John Hammond, the white producer who brought him to Columbia, and Tom Wilson, the black jazz connoisseur who replaced Hammond toward the end of the Freewheelin’ sessions. Wilson said he had never cared for folksingers, but Dylan reminded him of Ray Charles—especially the blues work, which was “raw, different from other whites, original.”

To my ears, Dylan’s first album sounds more raw than original, but the blues tracks he cut over the next year show a growing ability to twist familiar lyrics and improvise quirky variations. Unlike most white revivalists, who tended to repeat whatever verses Robert Johnson or Lemon Jefferson sang on a treasured 78, he treated blues as a living, changing tradition. In part, that was because he had direct connections to older artists: Suze Rotolo recalled him spending hours hanging out in John Lee Hooker’s hotel room, and other friends were struck by his close relationship with Big Joe Williams (although biographers are universally dubious, both claimed they’d met when Bob was a kid).

Williams and Hooker were masters of a tradition that took individual songs as points of departure, reworking old verses and improvising new ones to fit the moment and the mood. Dylan absorbed that lesson, taking favorite recordings as models rather than texts. In his memoir, Chronicles, he recalls Hammond giving him an advance acetate of Robert Johnson’s King of the Delta Blues Singers. That album has been the source of innumerable covers in the ensuing decades, most by sincere acolytes recycling Johnson’s phrases and mimicking his guitar licks. But Dylan describes a different process:

I copied Johnson’s words down on scraps of paper so I could more closely examine the lyrics and patterns, the construction of his old-style lines and the free association that he used, the sparkling allegories, big-ass truths wrapped in the hard shell of nonsensical abstraction . . .

Which is to say: the poetic Dylan wasn’t always chasing Rimbauds. (An awful pun, stolen from Dorothy Parker—but that’s part of the tradition, too. Witness Johnson: “A woman is like a dresser, some man’s always rambling through its drawers.”) Even his most abstract songwriting was deeply informed by his immersion in blues. When he got his first publishing contract, with Leeds music, the initial batch of demos included Guthriesque ballads, but also a rewrite of Johnson’s “Crossroads Blues” called “Standing on the Highway” and an extension of Howlin’ Wolf’s “Smokestack Lightning” titled “Poor Boy Blues,” in which he followed three of Wolf’s verses with a heartfelt moan well-suited to the baby-faced kid from Hibbing: “Hey, mister bartender, I swear I’m not too young . . .” He was recording for copyright men who wanted marketable product, but it sounds like he’s making up lines as he goes and would have sung something completely different on another day.

That’s the special excitement of Dylan’s blues work—the sense that every performance was being captured in the moment. The songs that happened to get preserved at any session were just a sample of what he was doing that week, and if he’d recorded a day earlier or later he would have done different ones, or the same ones in different ways. When he cut Johnson’s “Milkcow’s Calf,” he played piano on the first take, then switched to guitar for the second. At a live show a few months later, he was using his “Milk Cow” yodel for a Kokomo Arnold pastiche and singing Johnson’s “Ramblin’ on My Mind.” At a gig a few months after that, he sang Johnson’s “Kind Hearted Woman Blues” with a mix of old and adapted verses. We’ll never know what he sang on the nights that didn’t happen to get taped, or how he sang, just as we don’t know what Johnson himself sang thirty years earlier on all his unrecorded nights in bars and juke joints from San Antonio to New York City.

Listening to my imagined Dylan Blues album, I hear the flaws as well as the brilliance, and can’t argue with the choice to hold it back in favor of Freewheelin’ in 1963. But I still keep hoping it will be released, if only to complicate the familiar narrative of rock history. That narrative typically pairs Dylan with the Beatles in a pantheon of cultural revolutionaries who transformed rowdy teen dance music into a mature, intelligent art form. Blues comes into that story as a source of soul, guts, and drive, traced through Robert Johnson and Little Richard to the Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix. But the mature intelligence comes from elsewhere: the Beat poets, the French Symbolists, the literary traditions of Shakespeare and “Barbara Allen.” Dylan is the matchmaker who married folk ballads to Verlaine and Rimbaud, then shocked his early fans by backing those heady lyrics with a Beatle beat.

I’m switching out that narrative for another, in which Dylan was recording solid blues in 1962, experimenting with electric band tracks and the sparkling allegories of the Delta masters, and continued those explorations a couple of years later on Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61. The British Invasion opened a commercial door, but that music—the music of John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters, of Big Joe Williams, Mance Lipscomb, and Robert Johnson—didn’t need any lessons in maturity and intelligence from twenty-year-old rockers, Beat poets, or French Symbolists.

For half a century, as his literary gifts were analyzed ad infinitum and he was crowned with a bushy effusion of academic laurels, Dylan has continued to explore the blues tradition, growing occasionally beyond it but more frequently within it. The Nobel committee places him in the tradition of Homer and Sappho, but I prefer to think of him as a blues singer—and assume he would be the first to recognize that as at least an equal honor.