Unearthly Laments

By Christopher C. King

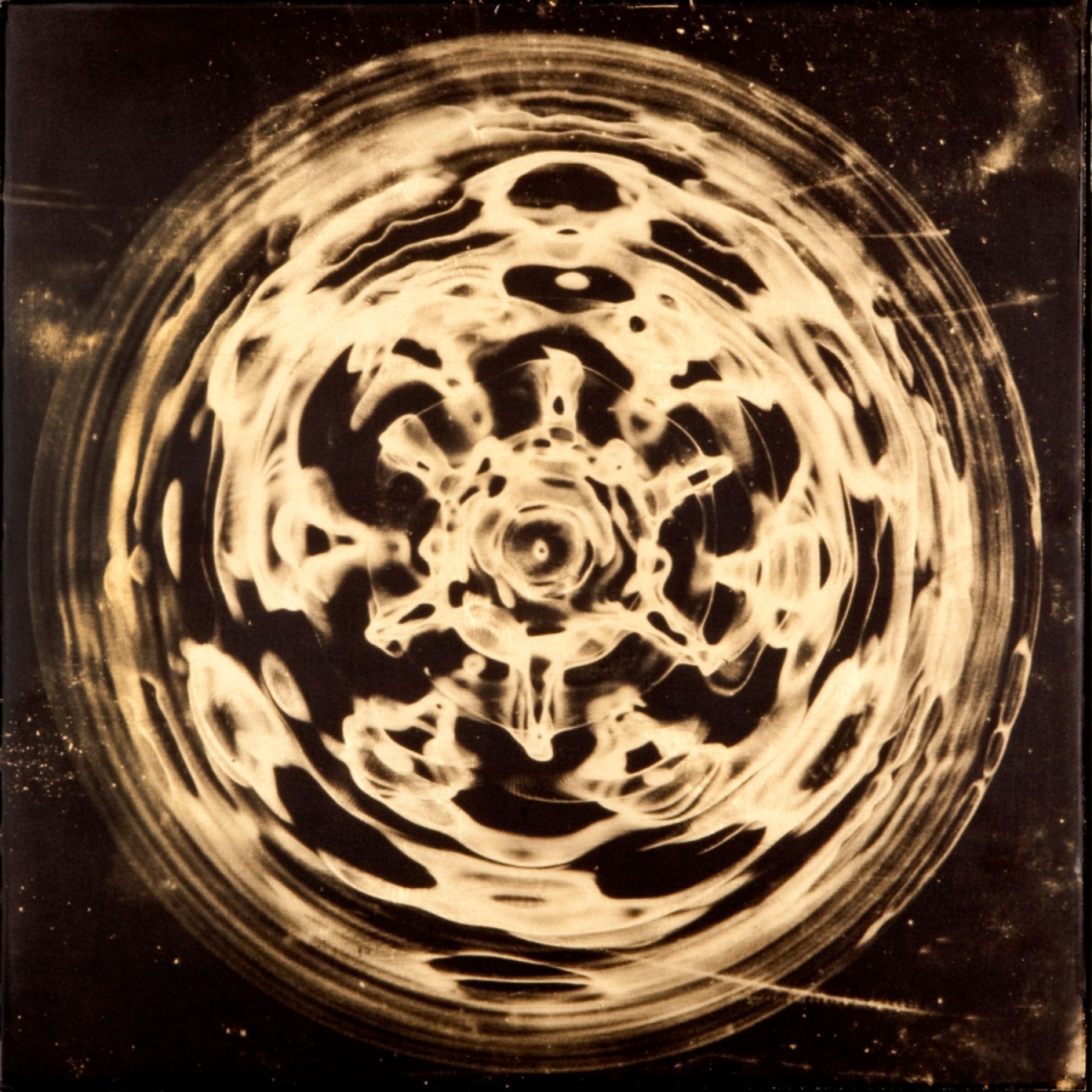

“Photograph in G#” (2015), by Louviere + Vanessa

Songs are just words. Those who are bitter sing them

They sing them to get rid of their bitterness, but the

Bitterness doesn’t go away.—Traditional mirologi from Potamia

Around two thousand years ago a woman died in Greek-speaking Asia Minor, near the ancient city of Aydin, in what is now Turkey. Her name was Euterpe, after the muse of music. Her husband or son, Seikilos—his relationship to Euterpe depends on how you read a gap in the dedication line—commissioned a stele, a stone memorial, which bore the following words, etched in Greek: “I am a tombstone, an image. Seikilos placed me here as an everlasting sign of deathless remembrance.”

Countless memorials have been unearthed throughout what was the ancient Greek world: the entirety of rural Greece is, after all, a burying ground. However, this tombstone—referred to as the Seikilos Epitaph—is decidedly unique. Written on the monument is the world’s earliest known complete musical composition with notation.

While you live, shine

Have no mourning at all

Life exists a short while

And Time demands its fee.

Etched alongside the single stanza of lyrics, a musical script indicates tones and intervals in the Ionian mode, a diatonic scale with a keynote and a repeated melody. Seikilos’s lament is the first complete written record of humanly organized sound. And it is a mirologi: metrical Greek folk poetry sung to remember the dead and the lost.

That Euterpe’s passing inspired this piece of ancient music is not extraordinary; music is a primary human salve against death and the loss it brings. And the impulse to communicate through music may indeed be more universal and instinctive than language itself. Writing in the second century a.d., the philosopher Sextus Empiricus recognized that music is “a consolation to those who are grief-stricken; for this reason, the aulos players performing a melody for those who are mourning are the lighteners of grief.” (The aulos is an ancient Greek double flute.) But how does one mitigate loss through music?

In grieving, we open two fathomless emotional reservoirs. One holds the memories of what was: recollection of the past. The other contains an amalgamation of expectations of what could have been: regret for the present and future. An abundance of ancient epigrams and mirologia addresses these two ceaseless founts of misery.

When we slowly and deliberately acclimate ourselves to the reality of a loss, an uncertainty forms about what lies ahead. This is the deeply human act of mourning, of grieving. A thoughtful look at our collective history of dwelling—and dying—seemingly affirms that if anything, we were made to mourn. We long, we remember, and then we regret: through this elongated process we slowly heal. But, is this not the same thing as feeling the blues? And when we reply to this misery in song—the most natural and primal response—is this not similar to singing the blues?

On December 3, 1927, a thirty-year-old blind guitarist and singer named Willie Johnson was led into a cramped, improvised recording studio in Dallas, Texas. The only known photograph of Johnson, probably taken that day, shows him uncomfortably wearing an angular suit, likely borrowed. He looks pinched, seated backward on a piano bench, a tip jar affixed to the headstock of his Hawaiian Conservatory guitar. He may have imagined himself in heavenly vestments as he played on the street corners of Dallas for tips and also to “catch” souls for Jesus. Born to first-generation freed slaves in Pendleton, Texas, Johnson was raised within the confines of a region struggling to reconstruct itself after the devastation of war. According to his widow, Willie’s stepmother blinded him as a boy when she threw lye water in his face. Little reason was given except that it was done out of spite, jealousy, to punish Willie’s father.

Like a biblical metaphor, on this December day the blind led the blind: Johnson was probably ushered into the makeshift recording studio on North Lamar Street by an older blind black man, Madkin Butler, his mentor and musical partner. A&R man Frank Walker, the Columbia Records executive who arranged the session, had scant idea what would be produced. Little fanfare was connected to this first field-recording foray in Texas. Talents—and the less talented—came and went.

The first four sides that Johnson cut for Walker were essentially blues songs recast in a religious mold. “I Know His Blood Can Make Me Whole,” “Jesus Make Up My Dying Bed,” “Nobody’s Fault but Mine,” and “Mother’s Children Have a Hard Time” were hollered—testified—in a fiercely jagged, chthonic voice. The tone of Johnson’s singing was as arresting and elemental as the messages of salvation and damnation he delivered on street corners fouled by sin and vice. Taken on their own, these four recordings would have been enough to prove Johnson’s greatness and singularity.

As he paused to adjust his guitar in the middle of this session, the stubble on his face was thinly glazed with clear sweat, glistening as if he had just been baptized. With his guitar tuned carefully to the open D chord, Johnson began sliding a glass bottleneck across the strings, playing a piece he called “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground.” Although the title is based on the first line of a Wesleyan hymn, “Gethsemane,” penned by eighteenth-century evangelist Thomas Haweis, there is very little melodic similarity with the English religious song. What Johnson conjured for exactly three minutes and thirty seconds was an ethereal instrumental lament—a mirologi—barely of this Earth. When the red light flashed three times to signal the approach of the dead wax—the end of the groove—someone tapped Blind Willie Johnson softly on the shoulder to conclude his playing.

I first heard this recording when I was fifteen years old. It was among a stack of 78 rpm discs that I retrieved from a shack on my grandparents’ property in Alleghany, Virginia. In the early 1930s, itinerant sharecroppers worked this land in southwest Virginia; the rotting structure on the fringes of the farm was the last remaining place that had housed workers drifting from door to door during the Depression.

One morning in August—what we referred to erroneously in this area as “Indian summer”—I was asked to clean out this shed before my grandfather burned it to the ground. The air was thin and dry, raspy—the only detectable moisture seemed to be contained within the spidery brown trickles of tobacco juice glistening in the sun at the corner of my grandfather’s mouth. His thin arm hefted a tin coffee can full of kerosene while his other pointed at the shack, blue veins translucent in the August sunlight.

The structure smelled like cancer, wrapped as it was in peeling creosote paper. With a crowbar I pried open the thin door. In the center of this room, still wallpapered with printed reportage from five decades past—BEARS IN RUSSIA DIG UP GRAVES FOR FOOD, one headline declared—was a rotting wind-up Victrola falling in upon itself. A hole had opened in the rusted tin roof, and dripping water had slowly reduced the phonograph to a heap of swollen, pulpy wood and pot metal. Several hornets’ nests—active and angry—clung to the ceiling above.

Next to this decaying machine was a tightly lidded box. Twisting off the top, I discovered that it contained almost two dozen old records, none recorded after 1930. To this very day, I have no idea who listened to these records before I salvaged them from the shack, or what happened to the ghosts who once owned them. Among these discs of blues, gospel, and Cajun songs was a nearly pristine copy of “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground.”

When I first played this disc in my father’s record room nearly thirty years ago, a yawning vastness opened up; the sounds of anguish and longing hollowed out a void within me but also implied that the world around me had been gutted, made empty. Both spaces, within and without, were hungry for the music that was echoing from my father’s phonograph. Perhaps at that moment I realized that I couldn’t live without this music and that my life would be spent searching for its source. This was the record—among a few others—that taught me how to listen for the imperceptible, for the sounds that unlocked things.

Played in the key of D, the piece follows the major pentatonic scale—with an open note, the low bass D, acting as a dark tonal center—yet lightly touches the minor pentatonic in the same key. The music floats freely with no beat, no rhythm, no time signature. Everything holds together and falls apart at the same instant. Moans and sighs parallel the guitar phrases, but there are no coherent vocals: only suggestions of agony. As the bottleneck wisps along the strings, repeated patterns and motifs, like the sounds of weeping and mourning, emerge from the guitar. A languid vibrato punctuates almost every phrase, and the passages themselves are repeated insistently. Every note and every space without a note is intentional; nothing is wasted.

Those who hear this recording have a visceral reaction. Most identify this as one of the purest examples of the blues. Undoubtedly, it is the blues, insofar as the modal pentatonic structure has defined the genre. But it also belongs to a species of music that came long before.

Six thousand miles from Dallas, in a remote part of the Balkan Peninsula, lies a literal and spiritual gateway between the traditional binaries of East and West: Epirus. Geographically, it is the area straddling southern Albania and northwestern Greece; it possesses an imposing mountain range, the Pindus, as well as a vast canyon, the Vikos Gorge. Musically, Epirus contains one of the most complex collections of harmonic expressions in Europe; the people and the very terroir of this area act to preserve and to promote an engaged community life where song and dance play a central role in group cohesion and cultural esteem.

Perhaps unique to Europe, Epirus is a place where distinct purposes and functions of tunes and melodic expressions are acknowledged and emphasized, where a repertoire has been preserved for hundreds (and maybe thousands) of years, and where an overwhelmingly deep symbiosis exists between performer and audience. Most importantly, Epiriotes still actively engage in what may have been the original function and purpose of music: a tool for survival and communal healing.

In Epirus, as in other rural pockets of Greece, the graveside singing of folk poetry like that etched on the Seikilos Epitaph remains a viable tradition. But almost completely distinct to this region is an instrumental version of these funerary laments—also called a mirologi. It is a wordless musical expression played on violin and clarinet that maps the contours and reflects the cadence of these ancient verses of sorrow.

Imagine a string of tones (in this case a distinct pattern of five notes) carefully shaped and crafted so that they are capable of transformative powers. Taken on their own, these notes would simply be sounds, vibrations in the air. But once organized, heard under certain conditions and within a specific context, the pattern can be understood as curative to the listener. The contemporary phrase psychologically medicinal would characterize such a phenomenon, such music.

This series of five notes—the pentatonic scale—is actually not so limited. A violin, a clarinet, a guitar can express four octaves quite easily. Within that range, there are almost endless permutations between the modulations of a major and minor pentatonic scale with the same keynote. Each one of these arrangements can contain subtle flourishes—elision, vibrato, ostinato, glissando—and each variation can express tension, release, or suspension. In this way, what appears on the outside as a limited musical vocabulary can contain within itself infinite nuances, producing a profoundly rich language.

A little more than a year before Blind Willie Johnson’s Columbia session, in September 1926, a short, doughy, and impeccably dressed musician ambled into the recording studios of Victor Records & Phonograph at 28 West 44th Street in New York. Tucked under his left arm was a weathered yet sturdy Lifton leather case containing a Ukrainian-made Homenick Brothers violin.

Alexis Zoumbas had immigrated to the United States in 1910. The mythology—the body of folktales built around Zoumbas like those around Delta bluesmen Charley Patton, Son House, and Skip James—described how he had fled Greece after coolly executing his porcine Turkish landlord by binding stones to his sides and casting him down a vacuous chasm, a void. But in reality, Zoumbas had simply done what countless male breadwinners from Epirus did before and after him: he moved to America so that he could earn money to send back to his family in Greece. The Zoumbas name—like the names Harisiadis, Tzaras, Halkias, and Kapsalis—indicates musical nobility in Epirus, but certainly not wealth. Alexis was from the village of Grammeno on the outskirts of Ioannina, the region’s largest city. Leaving behind his wife and two children, he sailed from the Ionian island of Corfu (Kerkyra in Greek) to Ellis Island. Crucial to his narrative—and ours—is the fact that Zoumbas did not know if he would ever return to his home soil.

By the time he came to Victor to record, his coal-black hair was flecked white along the temples. If we could read faces as we read maps, the topographical expression on Zoumbas’s visage was an overlay, a shared border with two distinct regions: an uncompromising confidence in his own skills and a calm, assured disdain for the efforts of others. Illustrator R. Crumb, upon finishing a portrait of Zoumbas from the only known photograph, said, “In the process of drawing him and having to look closely at the photo for several hours, I have changed my mind about Mr. Zoumbas. Close scrutiny of his face gradually revealed a sinister, dark side of his character, capable, perhaps, of anything.”

Zoumbas was, at the very least, a man incapable of questioning his own expressive power. Yet he had to acknowledge that the finest suits, which he could scarcely afford, would not hide his walnut-brown skin, the skin of a Gypsy—and the best-made violin would not cover up his thick Greek accent when he spoke. Zoumbas also had a slightly drifting and dropsical right eye, an anomaly common with the Roma of northern Greece. This marked him as spiritual kin to the poor, blind, black musicians of the American South: marginalized with little chance of economic mobility. Until World War II, many of the popular rural black music makers came with the prefixed moniker indicating loss of the visual dimension: Blind Joe Reynolds, Blind Blake, Blind Lemon Jefferson, Blind Willie McTell. Blind ad nauseam.

Alexis was led to a rather confining room trimmed in oak. Thick brown tapestries were angled in the corners so that from every point he turned, he was surrounded by draped envelopes of wool. He stepped forward onto a richly piled rug that ran from edge to edge of the room. Soft right angles formed where the rug met the wooden wainscoting. Suspended from the ceiling was a shimmering chrome case: a very early prototype of the first RCA electric microphone. A thin, fragile metallic ribbon encased within the porous chrome box was itself suspended—caught—in the center of a metal circle by eight long, taut springs.

Within an hour of walking into this room with LeRoy Shield, the legendary Victor Records A&R man, Zoumbas had recorded three traditional instrumentals from Epirus, dances lightly accompanied by san (a hammered chordophone) and contrabass. Then the mood in the room shifted—turned dark and bruised—as he prepared to record his mirologi. The san player was excused and as Zoumbas rosined his bow he instructed the contrabass player—unlisted in Victor’s ledger sheet from that day—to play only the open D and the open G. “Never lift your bow from the strings,” he said over his shoulder.

When the light flashed green three times, the first four notes of “Epirotiko Mirologi” (A Lament from Epirus) vibrated from Zoumbas’s violin. For exactly four minutes and sixteen seconds, he would play an ancient instrumental lament in the key of D, primarily in the major pentatonic scale but with three passages in the minor pentatonic lasting no more than ten seconds per section. It was only during these three brief phrases that the contrabass moved from the low D note to the low G, creating the eternal tension and internal magic heard in Epirotic music. The bow never left the strings, providing a constant drone, a dark tonal anchor, over which Zoumbas’s violin fluttered, wept, ascended, levitated, and cried like a wounded bird. There was no beat, no rhythm, no time signature. Everything held together and fell apart at the same instant.

A discerning listener from northern Greece who hears this record would likely mention one thing: the profound sadness of this piece has no closure, no resolution; this is quite different from what they would hear at a paniyeri, the feast celebration where this music is heard in its best form. This mirologi sounds dismal, aching, and wounded precisely because it is being played thousands of miles away from Epirus, a place that—in 1926—Zoumbas did not know if he would ever see again. Xenitia—one’s longing for one’s home soil and the reciprocal yearning from the people of the village for the exiled person to come home—imbues this piece of music like no other.

Alexis Zoumbas’s recording of “Epirotiko Mirologi,” although thoroughly traditional, had transcended whatever restraints had been imposed on the form for thousands of years. The distinct species of anguish—of xenitia—grafted onto and translated into this performance by Zoumbas made it sui generis: an apogee of expression, peerless.

The first time I played “Epirotiko Mirologi,” a dark vastness opened up within me, almost identical to the void created when I first heard “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” twenty-five years earlier. When the needle dropped into the groove, I perceived an unwinding in myself: an exploration of private, internal space. I felt as if I were witnessing an agonizing crucifixion but was unsure of the victim.

The record is not vexingly rare. Not like other 78s—those by Willie Brown, Son House, Geeshie Wiley—that goad along the collector’s monomaniacal hunger. This recording by Zoumbas, like several of those by Johnson, actually sold well. But what is rare, what is perhaps singular about music captured on these curious black discs, is this: they are mystical apertures leading to discrete, long-gone places. Records such as these allow us to refract time through the prism of sound.

From the moment I heard the record until the moment I write these words, I’ve wondered what turmoil Zoumbas was experiencing; what was he thinking and feeling as he played? What was the emotional landscape that surrounded and created this particular mirologi?

The closest approximation to an answer I have encountered appears in Milan Kundera’s novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting. A word exists exclusively in the Czech language: litost. Kundera writes, “As for the meaning of the word, I have looked in vain in other languages for an equivalent, though I find it difficult to imagine how anyone can understand the human soul without it.” The definition he offers is “a state of agony and torment created by the sudden realization of one’s own misery.”

Gazing up at the blinding Indian summer sky when I was fifteen, I watched the thick pillar of black smoke curling from the sharecropper shack consumed in a tremendous crackle of flames. If the hundreds of hornets dying at that second produced a sound, it was obscured by the incineration of their home; the match my grandfather tossed onto the old wood was like an asteroid that had wiped out their planet. Next to me on the ground was the box of 78s I had saved, including “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground.” I was yet unaware of its unfathomable aura and power; that this would be my own “Great Whatsit,” teeming with unimaginable dark energy.

In 1986, while the smoke rose from our insignificant farm in the Highlands of Virginia, the space probe Voyager 1 was traveling toward the edge of our galaxy. Just as I was clueless as to the contents of the box at my feet, I was then ignorant of the NASA mission launched in 1977. Conceived as a device to explore and document the realm of the celestial bodies, Voyager 1 was also designed as a cultural offering, a time capsule of sorts, blasted into outer space as a “calling card” for any intelligent life that might exist beyond Earth. Housed within the interstellar explorer, a gold-plated copper disc contains a variety of languages, images, and music—information that introduces us humans. I like to imagine an introductory message engraved on the outside of the probe, a pathetic profile page for intergalactic social media:

Here are some things about us. We number in the billions (and growing!). Some of us are single . . . :)

We use language, art, and music to express ourselves.

We teach. We listen. Sometimes we put out records.

Carl Sagan and his team of scholars were tasked with selecting the contents of the disc with the intended purpose of conveying to alien beings the diversity of the culture and landscape on Earth. They believed rightly that an essential part of our collective psyche is our ability to articulate feelings through music, and so they provided a range of selections demonstrating this human phenomenon. A combination of emotional and psychological states—longing, remembrance, regret—appeared to them to be contained within one song: “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground.”

With synchronicities and commonalities so perfectly mappable and mirrored between Blind Willie Johnson’s 1927 masterpiece and Alexis Zoumbas’s 1926 mirologi, one could easily replace each recording with the other. Or, perhaps both pieces of music should have been etched on the golden record. This would have shown something even more profound about humanity than just our skills at translating feelings into music; it would demonstrate that our ability to articulate grief through music is deeper than the veneers of language and geography: in the case of these two songs, an arc that stretches from Texas to northern Greece.

In 2012, Voyager 1 left our solar system and entered interstellar space. It will be another 40,000 years before the probe will approach a star within another solar system. During that time, perhaps a cold mass of rock—an interloper in our galaxy—will careen into our planet and tear everything asunder. Were this to happen, there would be an unintended consequence for the space probe and those who forethought its purpose. Voyager 1 would not contain evidence of the biodiversity and cultures of Earth, but rather the recollection of what once was—an everlasting sign of deathless remembrance.

Maybe aliens will retrieve the probe and play back the golden disc. Maybe they will hear “Dark Was the Night, Cold Was the Ground” and speculate about the function for this piece of music, what was being expressed by its creator, and wonder if this now extinct life form produced anything else like it.

Adapted from Lament from Epirus by Christopher C. King. © Christopher C. King. With permission of the publisher, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.

“Epirotiko Mirologi” by Alexis Zoumbas is Track 18 on the “Visions of the Blues” Southern Music Issue CD.