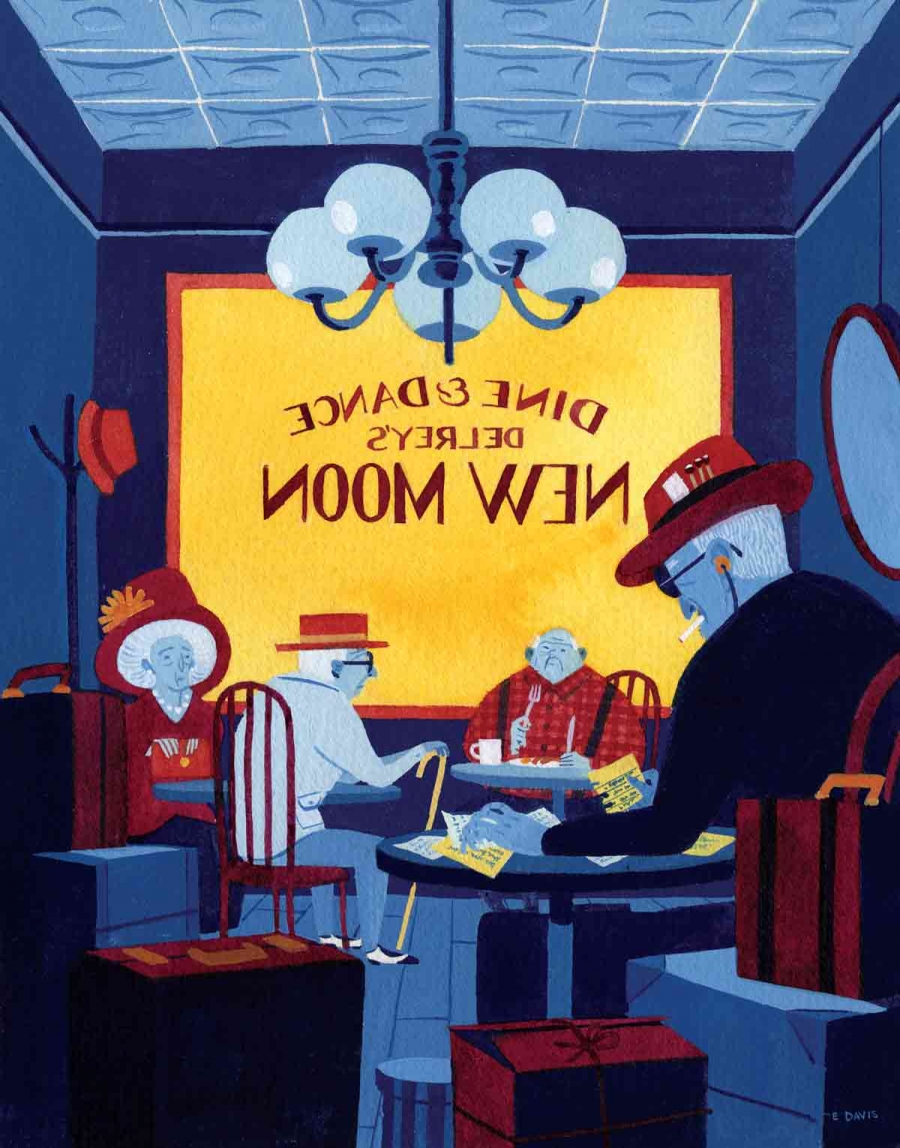

Illustrations by Eleanor Davis

Delray’s New Moon

By Charles Portis

This feature was published in our Fall 2012 issue.

Making Night Club History

Introduction by Jay Jennings

If Charles Portis’s aversion to publicity has sometimes led to periods of relative obscurity, his five novels, including the classics True Grit and The Dog of the South, have long been the kind of books that readers passionately press on friends and then insist that they return. Such readers as varied as Roy Blount, Jr., Donna Tartt, Conan O'Brien, and George Pelecanos have named him as a favorite.

Following the Coen Brothers’ 2010 remake of True Grit, a new generation has been discovering (just check Twitter) that Portis’s lucid style and droll observations are as fresh and relevant and funny as when the novels were originally published. But even his most fervent fans, old or new, may not know that he is also a playwright, having created characters for the stage as indelible as those in his novels.

In 1996, Cliff Baker, the producing artistic director of the Arkansas Repertory Theatre in Little Rock, heard that Portis had written a play. A friend put him in touch with Portis (who lives in Little Rock) and, after their meeting, Baker agreed to do a workshop production of Portis’s Delray’s New Moon. The writer, Baker says, “wanted to hear it with actors and see what it was.”

After two weeks of rehearsals, the play opened on April 18 of that year with a cast of fourteen. The action takes place in a rooming house/café, where a dreamer named Delray is scheming to convert the place into a swank (to his mind) supper club. The cranky and memorable senior citizens who are being displaced are in revolt.

The Arkansas Democrat-Gazette called the play “hilarious.” Portis even stuck around after the opening-night show for a “talkback” with the cast, director, and audience. Word circulated among cast members that HBO somehow got wind of the production and was interested in the work. “I remember thinking at one point that it might make a more interesting screenplay,” Baker says, “because so much of the talking is visual—the characters describing the town, the situation—as opposed to making a statement.”

After the two-week run, Baker says he had the impression that Portis’s questions about how his play would sound onstage were answered “and he didn’t want to spend more time on it at this point in his life.” While Baker would have liked to pursue the project further, he respected Portis’s immediate goals: “He’s such a smart man. This idea of doing it the way he wanted to do it, I didn’t have any problem with that because the whole purpose was for him to explore the piece, not for the Rep to have its own show.”

Working toward a full production may have required more collaborative energy than a shy author is comfortable with, but for the audience the result was a fully realized Portisian experience, full of inventive language, opinionated oddballs, and waves of laughter. In this excerpt from the first act, the reader here will get the same.

Delray’s New Moon

Cast of Characters (in order of appearance)

MR. NIBLIS. A skinny old man wearing mismatched suit coat and trousers, white shirt and short, wide necktie. He has a sack of tobacco in his shirt pocket, and keeps his cigarette papers and his matches (big kitchen matches) in the hatband of his felt hat. He rolls and smokes cigarettes throughout the play. One lens of his eyeglasses is dark. He wears a hearing aid, with big conspicuous wires running down from his ear to his clothing.

MR. PALFREY. An old man in nondescript gray trousers, wide suspenders, and plaid shirt buttoned all the way to the top. He wears an old felt hat with a narrow brim, and uses a walking stick, an unpainted cane of white wood.

FERN. Mr. Palfrey’s older daughter, who is about fifty years old. Her clothes are neat and plain.

KATE. The waitress, a girl in her mid-twenties. Hard and tense.

MARGUERITE. A slender little girl about nine years old, with stringy blond hair. She wears old white tennis shoes with no laces, and a shiny blue-green dress with shoulder straps. One strap keeps falling off. She sells pecan rolls from a paper shopping bag.

DELRAY SCANTLING. The new owner, he is about forty years old, wears a white guayabera, short white slacks, soft white loafers, gold necklace. He carries a ring of keys on his belt.

DUVALL. He is Delray’s assistant, a young man about twenty years old. He has a reddish ponytail, tied with a ribbon, and wears jeans and T-shirt.

MR. MINGO. A dapper old man in a seersucker suit, polka-dot bow tie, straw boater hat and two-tone shoes, black and white. He uses two malacca canes.

MRS. VETCH. An old woman, very ladylike, wearing her Sunday best—hat, purse, and gloves.

ACT I

The only occupant of the room is Mr. Niblis. He is seated at a table surrounded by luggage and pasteboard boxes tied up with string. He is smoking one of his hand-rolled cigarettes and is reading from scraps of paper that he takes from various pockets.

Enter Fern and her father, Mr. Palfrey, through the front door. She carries two suitcases and leads the way. He follows, rocking from side to side on his walking stick.

FERN: Well, we beat the rain anyway. (She sets the bags down beside a vacant table and looks about) I wish you would look. They’ve sure changed the old Sunnyside all up.

MR. PALFREY: (Looking at sign) Dine and dance. Dine and dance. Everybody wants to dine and dance.

FERN: (Getting him settled in at a table) Now just sit down there, Daddy, and be still. Don’t stare at people and don’t act ugly to people.

MR. PALFREY: (Not listening. Pawing over his things) You forgot my pillow.

FERN: I’m going after it now. You just stay right there.

She starts to go, comes back, removes the hat from his head, combs his tousled hair. She leaves. Mr. Palfrey and Mr. Niblis stare at each other, look away, stare again.

Enter Kate, the waitress, from the kitchen. She goes first to the front window and peers outside, looking left and right. Then she goes to Mr. Palfrey’s table and gives him a menu. He puts on his glasses and looks it over.

MR. PALFREY: These are just dime-store glasses. That’s all I ever needed. I haven’t been to a doctor in twenty-one years. And don’t plan to go any time soon, thank you.

He waits for her to marvel at this but she doesn’t respond. He peers at the name tag on her uniform.

MR. PALFREY: “Kate,” is it?

KATE: Yes.

MR. PALFREY: Well, Kate, tell me this. What time do the good-looking women come on?

KATE: (In no mood for this banter) Much later. What do you want?

MR. PALFREY: Can I still get breakfast?

KATE: (Looks at watch) Till ten-thirty, yes.

Mr. Palfrey, humming and tapping his fingers, continues his leisurely study of the menu.

KATE: (Impatient) If you don’t know what you want, I can come back.

MR. PALFREY: Oh, I know what I want. I just don’t see it here. What I want is a fat yearling coon roasted with some sweet potatoes. What I want, young lady, is some salt-cured ham that’s been hanging in the smokehouse for about two years, along with five or six big cathead biscuits, and some country butter and ribbon cane surrup. But I can’t get that, can I?

KATE: You can’t get it here.

MR. PALFREY: You can’t get it anywhere. Not any more. Them days are gone. It’s a different country. Way too many new people to suit me. (Resumes study of menu) All right. Let me have this Number One. With bacon and grits. These biscuits—are they canned?

KATE: Yes.

MR. PALFREY: Then let me have toast. Are the grits soupy?

KATE: I don’t know. They’re just instant grits.

MR. PALFREY: I like my grits to stand up. Tell the cook. But not lumpy, either. And I want tomato juice instead of grapefruit juice.

KATE: (Points to warning words in menu) “No Substitutions.”

MR. PALFREY: Yeah, I know, they all say that, but what difference does it make?

KATE: I don’t know. That’s the rule. I just work here. How do you want your eggs?

MR. PALFREY: (Sulking) I can’t have what I want.

KATE: You can have your eggs the way you want them.

MR. PALFREY: No, I can’t either. Not here. Not in this place.

KATE: Fried, scrambled, what?

MR. PALFREY: Nobody can have anything the way they want it here. The customer is always wrong.

KATE: Over easy then?

MR. PALFREY: I don’t have no say in the matter. Bring me whatever you want me to have.

Kate shrugs and leaves with order.

MR. PALFREY: (Calling after her) Wait! Here's my old-man card. I get ten percent off.

KATE: You don’t need a card. (Exits to kitchen)

Fern returns with his special pillow.

FERN: For just once in her life, I wish Lenore could be on time someplace. “Ten o’clock,” she said. “Tonya and I will be there waiting for you!” I should know better by now.

MR. PALFREY: She’ll be here. Don’t worry. Just go on back to Texarkana. I’ll be all right.

FERN: No, I’m not going to leave you here by yourself. You could be sitting here all day waiting for Lenore.

MR. PALFREY: She probably got caught in the rain and had to slow down some.

FERN: Then she should have made allowances for the rain. You always make excuses for her, Daddy.

MR. PALFREY: Well, she is my baby daughter, after all.

FERN: A pretty old baby, if you ask me.

MR. PALFREY: (Looking over his things. Speaks up suddenly) Where’s my police scanner?

FERN: Didn’t you put it in the trunk?

MR. PALFREY: It was on the kitchen table. You were supposed to load it.

FERN: Well, let me go look. (She leaves)

MR. PALFREY: (Calling after her) And my umbrella! And my big flashlight!

Enter Marguerite, the little girl. She is lugging a paper shopping bag that contains candy logs—big pecan logs. She approaches Mr. Palfrey and looks at him.

MARGUERITE: Are you a cripple old man?

MR. PALFREY: No, I’m not.

MARGUERITE: You have a walking stick.

MR. PALFREY: It’s not a walking stick, it’s just a stick I have to poke things with. I point at things with it and I knock down pears and apples out of trees with it. You don’t see me creeping around, do you, and grabbing aholt of chairs when I cross a room?

MARGUERITE: (Brings out big bar of candy wrapped in cellophane) These are real good pecan logs and they only cost five dollars.

MR. PALFREY: (Fondling his stick) Look how pretty the wood is. That’s holly. The whitest wood there is. I cut it and turned it myself. (Whacks it across his palm) And sometimes I use it to correct my chirren with.

MARGUERITE: (Presses candy on him) They call this the family size. The money goes for our new band uniforms. We’re going to have brand-new scarlet and gold uniforms.

MR. PALFREY: (Puts on glasses, looks over candy) It looks like a ear of corn. A big roasting ear. (Reads label) I never heard of this outfit. Just some post-office box in Memphis.

MARGUERITE: (Hanging over his shoulder, pointing to label) No, see, it says “Made of the finest ingredients.” And look how many pecans you get for just five dollars.

MR. PALFREY: (Pushing her back) Here, get away so I can see for myself.

MARGUERITE: They can’t sell these in stores because they’re too big and they have too many pecans. Mrs. Vetch has been eating on hers for more than a week.

MR. PALFREY: (Pitches candy into shopping bag) No, I can’t use it. But I tell you what I will do. If you can make me laugh, I’ll give you ten dollars.

MARGUERITE: (Thinks it over) I can dance some. (Twirls about and curves her arms up in Spanish dancer pose) Next year, I’m going to take tap lessons at Irene’s House of Dance.

MR. PALFREY: Dancing? How would that make me laugh?

MARGUERITE: They’re going to have dancing here pretty soon and I’m going to be right in the middle of it. With sequins in my hair.

MR. PALFREY: No, you’re not. This place is turning into a honky-tonk. They’re not going to let you come into a honky-tonk.

MARGUERITE: Delray said I could come as a performer. He said he would introduce me as “the radiant Miss Annabel” when I do my scarf dance.

MR. PALFREY: You’re Annabel?

MARGUERITE: That’s only my dancing name. My real name is Marguerite, which means “pearl.” You know what though? (Hands on hips) My birthstone is the beautiful blue sapphire! But my favorite color is cerise!

MR. PALFREY: “Annabel.” (Savoring the name) “Annabel.” That’s not bad. “Blanche” is a good name, too. If I had another little baby girl I would name her Blanche.

MARGUERITE: No, I like “Annabel” better. I read this real real good book, see, called “The Radiant Miss Annabel Lee,” about a poor orphan girl with long auburn hair. It was her crowning glory. It was so long she could sit on it but the boss made her cut it off when she went to work at the fish-canning factory. But she didn’t let it get her down. She always made the best of everything. She nursed injured animals back to health and she threaded needles for the old ladies. She cheered up people with broken hearts. She wrote love letters for people who couldn’t write very good love letters. Annabel loved children, too, and she wrote tiny poems in green ink on their little fat hands. She took them out blackberry picking and when the little ones got tired and cried and dropped their buckets she showed them how to do the chicken walk and soon turned their tears to bubbling and infectious laughter. And everywhere she went everybody just loved Annabel so much because she helped them out with their problems. And they all said the same thing about her. They all said, “How fortunate we are to have Annabel here with us! How radiant she is!” And that’s how I got my dancing name.

MR. PALFREY: Well, I don’t care nothing about your boogie-woogie or your rock & roll or your nut logs. My deal is this. You make me laugh and I’ll give you a ten-dollar bill.

Enter Kate with coffee and food. Marguerite lingers by the table and watches Mr. Palfrey salt and pepper his fried eggs, heavily, with both hands.

MARGUERITE: Oooooo! I hate grits!

MR. PALFREY: You don’t know what’s good, girl. I eat grits every day. They keep my coat glossy.

MARGUERITE: (Speaking up, just as he is about to attack his eggs with knife and fork) We say the blessing at our house before we eat.

MR. PALFREY: We do, too, but when you’re out on the road, you don’t always have time for that. (Trails off as he is made to feel the lameness of the excuse) All right then. (Drops his head a bit and mumbles the prayer rapidly and mechanically) Bless this food to the nourishment of our bodies and consecrate our lives to thy service in Jesus name amen. (He falls on the eggs with knife and fork, with furious criss-cross chopping moves. Marguerite, startled by the clatter of cutlery on china, jumps back)

Enter Delray from the rear hall. He comes striding in to investigate the noise and looks at Mr. Palfrey with disgust.

DELRAY: What the devil! Kate! Duvall! Where is everybody? Kate!

KATE: (Sticks her head out kitchen door) What? What is it now?

DELRAY: (Pointing to Mr. Palfrey) There! That’s what! We’re not supposed to be open!

KATE: Why not?

DELRAY: Didn’t Duvall tell you? Everything was to be shut down last night.

KATE: Nobody told me anything. Sammy came on as usual. He’s back here in the kitchen.

DELRAY: Well, tell him to shut it down right now and get everything cleaned up. I want it all ready for a complete inventory. No, forget it, I’ll tell him myself. That’s the only way I can get anything done around here. (Exits through kitchen door, pushing Kate aside)

MARGUERITE: (To Mr. Palfrey) Wait! I know! I’ve got something at home to show you! It’ll make you laugh out loud! It’s worth ten dollars easy! Watch my sack for me!

She takes off at a run and exits through front door. There are noises of people on stairs. Duvall, Delray’s young assistant, enters on the stairway with two old people, Mrs. Vetch and Mr. Mingo. He helps them along and settles them in at a table near Mr. Niblis, where their luggage is gathered.

DUVALL: There we go. All set, are we?

MRS. VETCH: (Looking about) Where is Ruth Buttress?

DUVALL: She’s on the way. You’ll be off to Avalon in no time and, you know, I’m tempted to go with you. (Reads from brochure) “The days are full at Avalon and before you know it, it’s bedtime!”

MR. NIBLIS: (Speaking for the first time) What was that? What did Duvall say?

MRS. VETCH: He said the days are full at Avalon!

DUVALL: Are they ever! (Runs finger down Avalon brochure, reads from it) Bingo, bridge tournaments, sand modeling, sing-alongs, paper folding, balloon twisting, sack race, bottle race, wheelchair race, aerobics, piñata smashing, tug-of-war—the eighties versus the nineties on Tuesdays—

MR. MINGO: Yes, we’ve read all that, Duvall.

DUVALL: Well then, let’s get into the spirit of the thing. Why don’t we give a cheer? “We’re off to Avalon!” Okay? All together now. With me. You too, Mr. Niblis. (Raises hands in manner of song leader) WE’RE OFF TO AVALON! (But no one joins in) All right then, how about some coffee?

MR. MINGO: Yes, please.

MRS. VETCH: A cherry Coke for me, Duvall. In a glass, please, not a plastic cup.

DUVALL: Hey, you got it! Coming up!

Duvall exits to kitchen. Mr. Palfrey stares at the other old people. They steal glances at him. Finally, Mr. Mingo speaks to Mr. Palfrey.

MR. MINGO: Haven’t I seen you here before?

MR. PALFREY: Who are you?

MR. MINGO: I am Mr. Mingo.

MR. PALFREY: How old are you, Mr. Mingo?

MR. MINGO: I am carrying ninety-nine years on my back, sir. I am at death’s door.

MR. PALFREY: You look old but you don’t look that old.

MRS. VETCH: He’s really only about eighty-six.

MR. MINGO: Life plus ninety-nine years. That was my sentence.

MR. PALFREY: I knew he didn’t look that old.

MR. MINGO: The terms to run concurrently.

MRS. VETCH: Eighty-seven, I think, or eighty-eight.

MR. MINGO: Could be. Maybe so. I wouldn’t be surprised. Something like that.

MR. PALFREY: He looks all broke-down and wore-out but I knew he didn’t look that old.

MR. MINGO: I’ve seen you here more than once.

MR. PALFREY: Well, we’ve been stopping off here for two or three years now. Fern likes the lemon icebox pie. They always set a good table here at the Sunnyside. Sometimes we stop here and sometimes we stop at that barbecue joint down the road.

MRS. VETCH: You can forget about the lemon pie.

MR. MINGO: They no longer set a good table here. Miss Eula’s gone, you know. She sold out to Delray and we’re being evicted. Mrs. Vetch and I are the last of the old residents. And Mr. Niblis there. He likes to keep to himself.

MR. NIBLIS: Only when I’m reflecting on things. Naturally, I don’t like being disturbed when I’m reviewing my life.

MR. PALFREY: I thought he was deaf and dumb.

MR. MINGO: Oh, he can hear well enough. That’s a dummy hearing aid. There’s no battery in it. He only wears it to discourage conversation.

MRS. VETCH: They’re hauling us off in a dump truck today. They’re going to dump us at the Grim Hotel in Texarkana.

Duvall reenters with tray of refreshments.

DUVALL: I don’t know why you keep saying that, Mrs. Vetch. You know very well it’s Avalon you’re going to over in the beautiful Chinkypin Forest.

MRS. VETCH: Same thing.

DUVALL: Not at all. No comparison. Night and day. And you’re not going away in a truck. Ruth Buttress is coming to pick you up in a nice air-conditioned van with captains’ chairs.

MRS. VETCH: But I’m just so worried, Duvall. They came over and signed us up so fast. I’m just so afraid of what we’re getting into.

DUVALL: Listen to me. You’re going to make a lot of new friends at Avalon and have loads of fun. You won’t have time to mope, with all your leather-craft classes and your essay-writing contests and your field trips to paper mills and bakeries. (Takes brochure from hip pocket) And look here, when the weather is nice there’ll be folk dancing on the lawn and some of the great old games you played as a child. Pop the Whip, Piggy Wants a Motion, Red Rover. Yes, you’ll join hands and roar out your challenge to the opposing team—“Red Rover, Red Rover, let—” (He looks about) “—let Mr. Niblis come over!” And he’ll hurl himself at your line, trying to crash through. Then a good supper, and a nice visit with your new friends, and then maybe a thrilling love story on television, and before you know it—it’s bedtime.

MRS. VETCH: But what about my privacy?

DUVALL: Oh...you’ll have a certain amount.

MRS. VETCH: Can I take my small traveling iron? Some of my things I just don’t trust anybody else to press. I asked Delray about it and he didn’t know.

DUVALL: Iron. That is a puzzler. Let me make a note of that. (Takes pen and notebook from shirt pocket and writes slowly, speaking aloud the words) Memo...Mrs.Vetch…for Ruth Buttress...a request...to keep...one...small...personal...portable...traveling...heating...and pressing...appliance. (Claps notebook shut and puts it away with a smile) There. Leave it to me. It’s in my hands now. (Goes to bar, begins unpacking cocktail glasses from box)

MR. MINGO: (To Mr. Palfrey) Don’t you live in Texarkana?

MR. PALFREY: Well, I do and I don’t, Mr. Mingo. I stay there part of the time with my daughter Fern—she’s out there fooling around in the car—and then I stay for a while with my baby daughter Lenore in Little Rock. They trade me off, you see. I meet myself coming and going. It used to be a year at each place. Then it was six months. Now it’s down to three. Right here is where they trade me off, at the halfway point. Here or down there at the barbecue joint.

MR. MINGO: And you are—

MR. PALFREY: Mr. Palfrey.

MR. MINGO: Palfrey, yes. Now I have it. I’ve heard Mr. Ramp speak of you.

MR. PALFREY: (Looking about) Where is Ramp?

MR. MINGO: Oh, he’s been gone for several months now. When was it?

MRS. VETCH: About the same time Miss Eula left.

MR. NIBLIS: Ramp is on the run. He’s traveling incognito.

MR. MINGO: He signed up for Avalon with us and then he just disappeared. We don’t know where he is. Somebody said they carried him off to a ranch in Oklahoma.

MR. PALFREY: An old man like that? I’ve heard of boys’ ranches where they take in these bad boys. I’ve heard of dude ranches. I never heard of an old-timer ranch.

MR. MINGO: Maybe I got it wrong. Maybe it was a camp or a farm.

MR. PALFREY: Well, tell me this, Mr. Mingo. What happened to the old Sunnyside? It used to be a nice clean family place to eat. Now it’s what, some kind of honky-tonk?

MR. MINGO: The county went wet, that’s what happened. They voted in liquor by the drink and Miss Eula sold out to this dancing fellow, Delray.

MR. NIBLIS: Delray has thousands of dollars.

MR. PALFREY: Everybody wants to dine and dance.

MR. NIBLIS: And if you leave ’em alone for more than ten minutes, they’ll be dancing around the golden calf.

MR. MINGO: I can’t really blame Miss Eula. She’s no spring chicken, you know, and good help is hard to get. So yes, now it’s a roadhouse.

MRS. VETCH: And Delray has kicked us out. They’re coming today to haul us off in a dump truck.

MR. PALFREY: Don’t you have any chirren to look after you?

MR. MINGO: I’ve got a son who has retired from the post office, but his wife won’t have me in the house. His small, birdlike wife. She says I make her nervous.

MRS. VETCH: My son was killed years ago in Korea. He was a brave and handsome captain in the paratroopers. He died on the field of honor. His daughter Jeannie is married to a clown in Shreveport. She’s a sweet girl, too, and she keeps after me to stay with her, but I couldn’t possibly live under the same roof with that fat clown she’s married to.

MR. PALFREY: What about—

MRS. VETCH: You don’t know what it is to outlive your only child.

MR. PALFREY: (Nodding at Mr. Niblis) What about him?

MR. MINGO: Mr. Niblis? Oh no, he’s an old bachelor. He has no family.

MR. NIBLIS: No, I’ve never been blessed with a wife. My mother was one of eleven children and my father was the youngest of seven brothers, and here I am a barren old man with neither chick nor child. One day I’ll have to answer for that. One day real soon now.

MR. MINGO: Not that he didn’t make the effort. He tells me he proposed marriage to three or four women along the way.

MR. NIBLIS: More than that.

MR. MINGO: He just couldn’t get very far with them.

MR. NIBLIS: I couldn’t get anywhere with them. One summer in Nashville, I was rebuffed by five women in a row. Some of those women were wearing hats and carrying purses—like Mrs. Vetch here—andsome were not. Every one of them found me unpleasant and rejected me out of hand.

MRS. VETCH: Can you wonder?

MR. NIBLIS: Still, it left me more time for my work. Women will take up a lot of your time. And then there’s the money. I’ve heard it takes a great deal of money to keep them fed and amused.

MR. MINGO: He claims to be a prophet. That was his work.

MRS. VETCH: He tried to kiss some of those ladies.

MR. NIBLIS: Not after I saw how much it alarmed them.

MR. MINGO: “Things are not what they seem.” That was his prophetic message.

MR. NIBLIS: Things are not at all what they seem.

MR. MINGO: You may be right at that.

MR. PALFREY: What did Ramp say when they came and got him?

MR. MINGO: I don’t know that he had any parting words. There was no formal leave-taking. Nothing in the way of a valedictory address. No one saw him go. He was just here one day and gone the next.

MRS. VETCH: Good riddance, in any case. That very disturbing smile! And his old baggy clothes, my goodness! Itwas like somebody else had dressed him.

MR. MINGO: Yes, as though he had been dressed hastily by employees of the state. He sneaked around a lot, too. You never knew what door he might pop out of next.

MR. NIBLIS: Look who’s talking about sneaks.

MR. MINGO: He would come out of his room every morning with that knowing smile on his face. I think he had something hidden away in there, perhaps some rare animal that would surprise us all if we knew what it was. Some small animal with a pounding heart. I had a good look around his room after he left, hoping to find some droppings. I intended to send them off for analysis and identification. But I found nothing.

MR. NIBLIS: We’ll never know now. What he was up to.

MRS. VETCH: And yet Miss Eula thought he was so clever and so handsome.

MR. PALFREY: I wonder if we’re talking about the same Ramp. The Ramp I know is a retired barber, a hard little pine-knot of a man. He has sharp features. He looks exactly like a fox.

MR. MINGO: Yes, that’s our Mr. Ramp.

MR. PALFREY: He smells something like a fox, too. Gives off a strong musky fox odor.

MRS. VETCH: That’s the very same man.

Fern returns with a big flashlight and an umbrella.

FERN: Well, I looked everywhere. That scanner is just not in the car.

MR. PALFREY: (Stunned) You didn’t load my scanner?

FERN: You had it last. Itwas there on the kitchen table with the cord wrapped around it.

MR. PALFREY: What am I going to do in Little Rock at night without my police scanner?

FERN: I’ll send it up to you on the bus tomorrow.

MR. PALFREY: That won’t do me any good tonight.

FERN: You can watch TV with Boyce and them tonight. I just called up there. No answer.

MR. PALFREY: She’s on the way, that’s why. How could Lenore answer the phone, if she’s on the road?

FERN: If she is on the road. Look, it’s already after eleven.

DUVALL: (Overhearing the remark) Eleven! (Drops his work with glasses and goes to small television set at other end of bar. Turns it on. The screen faces away from the audience, and only the murmuring sound of a football broadcast is heard)

MR. PALFREY: Folks, I’d like you to meet Fern, my oldest daughter and the biggest worrywart in Southwest Arkansas. Fern, this is Mrs. Vetch and this is Mr. Mingo. That’s Mr. Niblis over there.

Exchange of greetings.

MR. PALFREY: Listen to this, Fern. Mrs. Vetch’s daughter married a circus clown in Shreveport.

MRS. VETCH: No, it’s my granddaughter, and her husband is not a circus clown, he’s just a big coarse—buffoon.

MR. PALFREY: They’ve been living here at the Sunnyside and now they’re being kicked out so these new people can have their honky-tonk here.

FERN: Well, I declare. That’s awful. Where will you go?

MRS. VETCH: They’re hauling us off today in a dump truck. To the city dump.

MR. MINGO: It’s actually Avalon we’re going to.

FERN: Avalon? That’s the place they advertise on TV so much.

MR. MINGO: Yes, Dr. Lloyd Mole’s new place.

FERN: (Quoting from ad) “The days are full at Avalon and before you know it, it’s bedtime!”

MR. MINGO: That’s it, yes. Delray put the Avalon people on to us and they came over and signed us all up for the Special Value Package. One flat fee up front and no more worries.

MRS. VETCH: We signed up in a weak moment. It just sounded so good. One big payment and then no more worries. That’s the Special Value Package.

MR. NIBLIS: They didn’t sign me up for the Special Value Package.

MR. MINGO: No, somebody else paid Mr. Niblis’s fee. Some secret admirer.

MR. NIBLIS: Without asking me.

MRS. VETCH: You didn’t have anyplace else to go. You ought to be grateful. Nobody but Miss Eula would put you up for that little bitty Social Security check you get.

FERN: But why can’t you stay on here?

MRS. VETCH: I don’t know. Delray wants us out. And it’s just so hard to bear at my age. I kept my little room here so neat and clean. The food was so good. I had my pots of begonias on the windowsill. I had all my mother’s beautiful things around me.

MR. PALFREY: (Calling out to Duvall across the room) Hey! You! Booger Red! Shut that thing off! Nobody wants to hear that TV racket at this time of day! Your paying customers are over here trying to visit!

DUVALL: You’ll want to hear this. It’s the Arkansas-Texas game. It’s the early game today.

MR. PALFREY: Naw, we don’t want to hear that either. It’s way too early in the day for that. Just keep it down over there. (Then to others) They won’t let you have the kind of juice you want and then they try to run you off with all their TV racket.

MR. MINGO: I hope the Razorbacks can win, but, you know, I prefer a good high-school game. The boys seem to show more spirit.

MR. PALFREY: Don’t get me wrong. I like football myself and I want our boys to stomp the devil out of Texas anytime they can, but there’s a time and a place for things. A time and a place, Mr. Mingo.

MR. MINGO: I love the fall of the year.

MR. PALFREY: That’s me, too. I’ve always said that. Give me the fall of the year, when the crops are laid by, with nice cold mornings, and football and hunting coming in.

MR. MINGO: Don’t they hunt turkeys in the spring?

MR. PALFREY: Yes, but I don’t hunt gobblers. Never cared for it. Sitting real still on wet dirt under a bush all day. I stand up like a man when I hunt. I do all my hunting in the fall and winter when the trees are bare. With nothing green but the pines and cedars.

MRS. VETCH: The magnolia stays green around the year.

MR. MINGO: The holly, the cypress.

MR. NIBLIS: The live oak.

FERN: Mistletoe. The privet hedge. Various ornamental shrubs.

MR. PALFREY: Yes, I could have named all those and more, too, but pines and cedars are what you mostly see. And the truth is, I don’t hunt anymore at all. The government won’t let you kill but one or two ducks now and my loving daughters made me sell off all my dogs.

FERN: Now don’t start in on that again. You could have kept your dogs at Texarkana and you know it. It was Lenore who put her foot down on the dogs.

MR. PALFREY: But that wasn’t none of her doing. It’s the city of Little Rock that won’t let you keep dogs. Oh, two or three maybe, but they won’t let you keep a pack of dogs. I’ll tell you another thing. They’ll steal your dog in Little Rock. You have to watch him ever minute. They made off with Blanche one night. That was my last dog, Mrs. Vetch. Poor old Blanche.

FERN: Lenore said she was stolen anyway.

MR. PALFREY: (Notices Mr. Mingo flexing his fingers) What’s wrong, Mr. Mingo? That old “arthuritis” acting up on you?

MR. MINGO: I don’t know what it is. My hands don’t hurt anymore, they’re just cold and numb. My feet, too. Ice-cold extremities. It seems all my blood vessels are silted up. When I walk, my hip joints crackle like green sticks in a fire, and when I sit down, my legs go to sleep. I couldn’t stand up right now if the house was on fire. And when I lie down, I get throat spasms and my throat wants to close.

MR. PALFREY: It sounds to me like you’re about two-thirds dead, Mr. Mingo.

MR. MINGO: About half-dead, Mr. Palfrey, but you weren’t far off. I also have gravel in my kidneys.

MR. PALFREY: (Flexing his own fingers) Look at that. Look how limber they are. I still tie my own necktie ever Sunday morning.

Marguerite comes flying back in. She has a small color photograph.

MR. PALFREY: Well, look here. It’s little Miss Prissy again.

MARGUERITE: Here! This will give you a good laugh! (She looks at photo, laughs, then gives it to Mr. Palfrey) It’s worth ten dollars, easy. See. That’s my fat bulldog, Norris, and my fluffy black cat, Doris. They’re wearing cute party hats with rubber bands under their little chins, and look how they’re sitting at the table with the teacups. It’s a tea party. Norris and Doris, you see.

MR. PALFREY: Yes, I see that, but I don’t like the look out of this dog’s eye. I know dogs. I have a sure hand with dogs. One of these days this dog will tear that cat’s head off.

MARGUERITE: Oh no! Norris just loves Doris! They play together and they lap up their milk out of the same bowl. Sometimes we all dance together in the back of the new truck. I twirl my long red scarf around and around. They try to catch at it and we all get dizzy. And Daddy comes out on the front porch and says, “Hey, no dancing in the back of the new truck!” But we act like we don’t hear him and just keep dancing away like nobody’s business. (She whirls about, flinging her arms) WE’VE GONE CRAZY AND WE CAN’T STOP DANCING!

MR. PALFREY: Here now. That’s enough. (Grabs her arm)

MARGUERITE: You said you would give me ten dollars.

MR. PALFREY: (Holds out photo) Not for this.

FERN: What did he tell you, hon?

MARGUERITE: He said he would give me a ten-dollar bill if I could make him laugh.

FERN: (To Mr. Palfrey) Well. Pay her. She showed you a funny picture.

MR. PALFREY: It’s not funny enough.

FERN: Give her the money, Daddy.

MR. PALFREY: (Takes bill from snap-top coin purse and pays her. Taps finger on photo) Better not take this Norris to Little Rock. They’ll steal him up there before you can turn around good. Pen him up is my advice. Put a muzzle on him. He’s a bad boy, I’m telling you.

MARGUERITE: (Skips off with money, photo, and shopping bag. Pauses in doorway) Norris is not a bad boy! Norris just loves Doris! (Sticks out her tongue at Mr. Palfrey and exits)

FERN: (To Mrs. Vetch) But I don’t see why you can’t keep your rooms upstairs and let them have their dance hall down here. What will theyuse the hotel rooms for?

MRS. VETCH: I don’t know. Mr. Delray Scantling doesn’t confide in me. I have my own dark suspicions. Which I will keep to myself.

A pause, as they all think this over.

MR. PALFREY: I take it you are a Christian lady, Mrs. Vetch.

MRS. VETCH: Yes, and one of the most severe kind if you were thinking of taking some liberty.

MR. PALFREY: I was only going to say—

MRS. VETCH: (Raising hand) No, Mr. Palfrey, not another word on that, if you please. Shame on me for putting thoughts in your head.

FERN: (Rising, with purse) Is the ladies’ room still back there?

MRS. VETCH: Yes, it’s in the same place off the hall, but it doesn’t say “Ladies” anymore. Delray has painted a lady’s slipper on the door. With high heel and a big silver buckle.

Fern exits through rear hallway.

MR. MINGO: And he’s painted a top hat on the door of the men’s room. A black top hat, with stick and white gloves.

MR. NIBLIS: (Low grunts, murmuring)

MR. PALFREY: What was that?

MR. MINGO: Murmurs. He murmurs when he’s reviewing his life.

DUVALL: (Calls out across the room) Hogs on the thirty and driving! (Gets no response) The Texas thirty! (Still no response)

MR. MINGO: (Looking at Avalon brochure) Avalon. That’swhere they carried King Arthur, you know.

MR. PALFREY: Who?

MR. MINGO: King Arthur. He was wounded in battle. A terrible head wound. Ruth Buttress came by in her van and took him away to a place called Avalon. We hear nothing more of him after that.

DUVALL: (Claps both hands to his head) I can’t believe it! Another fumble!

Fern enters.

FERN: The strangest thing. There’s a man lying on a bed!

MR. PALFREY: Where? What bed?

FERN: Back there off the hall. There’s a kind of dark alcove with a bed in it. He’s lying there like a dead man with his mouth open.

MR. PALFREY: A dead man!

FERN: I didn’t say he was dead, I just said he looked dead. A man in white clothes. I didn’t want to touch him.

MRS. VETCH: In the alcove, you say. I don’t remember a bed back there. Do you mean a day bed or a couch?

FERN: No, it’s an ordinary double bed. An iron bedstead with a bare, striped mattress on it.

MRS. VETCH: But I don’t understand. A man sleeping in a public place like that.

MR. PALFREY: You don’t reckon it’s Ramp, do you? Barbers wear white. Maybe they didn’t carry him off to that death ranch after all.

MR. MINGO: I don’t see how he could have been lying there all this time.

MR. PALFREY: Unless he is dead and nobody noticed him. (To Fern) Is it a little old man with a sharp nose?

FERN: His mouth is open. I don’t know about his nose. It’s dark back there.

MR. MINGO: Wait. I know. It might be Kate’s boyfriend. Yes, it might very well be Prentice. Having a nap.

MR. NIB LIS: Prentice is a gangster.

MR. MINGO: A criminal anyway.

MR. NIBLIS: Prentice is a scoundrel.

MR. MINGO: A thief anyway. (To Fern) Is he wearing white jail coveralls?

FERN: White something. And heavy black shoes.

MRS. VETCH: Wearing his shoes on the bed?

MR. MINGO: I’ll bet it’s Prentice. Kate must be hiding him here.

FERN: Her boyfriend is a criminal?

MR. MINGO: Yes, and it’s hard to keep him in custody. He was in jail at Hot Springs until two or three days ago, when he climbed over the fence in the exercise yard.

MRS. VETCH: Kate says he’s not really a crook.

MR. NIBLIS: Barbers don’t wear heavy black shoes. They wear these soft white leather shoes with a lot of little air holes in them.

MR. MINGO: Prentice steals equipment from unguarded construction sites, with his lowboy trailer. He steals backhoes and front-loaders—these ungainly machines that creep about scraping the face of the earth.

MRS. VETCH: Now you don’t know that to be true, Mr. Mingo. Kate says it’s his brother-in-law that does all the stealing. He takes the lowboy trailer out at night without Prentice’s permission. She says the state police have had it in for Prentice for a long time.

MR. PALFREY: Itstill could be Ramp, you know. He’s not cutting hair anymore and he might have gone over to a heavier, darker shoe.

MR. MINGO: Unknown man on bed. Who could it be? That’s the question we need to address.

MRS. VETCH: We could get Duvall to look into it.

MR. MINGO: Yes, I think that might be the thing to do.

A pause. They all look at Duvall across the room but doand say nothing.

MR. PALFREY: If you could ever tear him away from his ball game. Well, what can you expect, Mr. Mingo, it’s a different country. These new people don’t want to work, not like you and me had to work, from daylight to dark, six days a week, rain or shine. Dine and dance, that’s all they want to do. When they’re not watching their TV shows. You and Mr. Niblis and me might cash in tomorrow. The last yellow jacket of the season might sting us to death. We might check out next month, with the first killing frost, but it won’t matter much, and you know why? Because we’ve seen the best of this country.

MR. MINGO: But you know, I never really did any hard work. I managed to escape all that. Nobody in the Mingo family ever put himself out much.

FERN: How did you make a living?

MR. MINGO: I spread panic for a living. I worked here and there for different newspapers.

FERN: You mean you wrote things in newspapers?

MR. MINGO: I’m afraid so, yes. The Mingos have traditionally gone into undemanding fields like that—journalism, government service, pharmacy, photography, usury. Mingos have been beekeepers, and night clerks in motels. They have operated small ferryboats at remote crossings on narrow streams. It was my curious fate to become a writer of newspaper editorials.

FERN: Really? That must have been interesting. It never occurred to me that—

MR. MINGO: No, you don’t think of them as being composed by anything human. It’s a dead form, like opera. It was dead when I started, too, but that didn’t discourage me. Day after day, I gave political advice, economic advice, military advice, agricultural advice. Lapidary comment for all occasions. I gave freely of myself.

MR. NIBLIS: Vain labor. All those idle words.

MR. MINGO: I offered artistic advice, engineering advice, cooking advice. I gave moral instruction. No one paid the least bit of attention to anything I wrote. I knew that, of course, but then a change came over me. I came to believe that people were, after all, listening to me, acting on my counsel, heeding my lightest word. It was a crushing responsibility.

MR. NIBLIS: One day real soon now, Mingo, you’ll have to answer for every last one of those idle words.

MR. MINGO: I spoke to my publisher about this feeling and he had me put away in a hospital. Quite a well-known clinic, specializing in the treatment of journalists and their delusions. Journalists and other bystanders, onlookers, eavesdroppers, and talebearers. It wasn’t a bad place. The doctors said I was suffering from intrusive thoughts. They put me on some dope and told me to eat a lot of bananas. I soon recovered. I was soon back at work, if you can call it that, and I did well enough for a time.

MR. NIBLIS: Spewing out more vain words.

MR. MINGO: No doubt, but they didn’t seem vain to me at the time. I was conscientious in my work. I was never afraid to be dull, for instance. To drone a bit.

MR. NIBLIS: Nobody will dispute that.

MR. MINGO: I did well enough for a time and then a darker change came over me. It was slowly revealed to me that my words were withering the grass and turning everything brown. I felt personally responsible for extensivecrop failures. So you can understand why I had to stop writing.

MR. NIBLIS: And how the readers must have cheered, Mingo, when you laid down your busy pen.

MR. PALFREY: But I don’t know why you had to stop writing. Things like that happen. I once give a man some mortgage advice and he lost his house. That didn’t stop me from talking.

MRS. VETCH: But I don’t see—I mean—surely yours were printed words, Mr. Mingo. It’s not as though you were speaking on the radio. And spewing your poison words willy-nilly into the air. Where they could then waft across the countryside and settle on the flowering crops.

MR. MINGO: Don’t ask me to explain the mechanics of it, Mrs. Vetch. I suspect the contaminants were not airborne, but something more in the nature of a malignant radiation. I can only tell you that I saw the blighted fields for myself, and how those fields were perfectlycongruent with the circulation area of my newspaper.

MRS. VETCH: Nobody would want to turn the earth brown with his words. No decent person.

MR. MINGO: No, indeed, and I saw then what I had to do. It was the only honorable thing I could do—take early disability retirement.

FERN: (Musing) “Intrusive thoughts.” I didn’t realize they could put you away for that.

MR. PALFREY: It’s amazing what the government can do these days. What these federal judges take on themselves. It’s a different country, Fern.

MR. MINGO: I was a middle-aged man when I received my first disability check. Young middle age, really. My face had not yet dropped, from gravitational stresses. My nose and ears were still of modest size. That was many years ago and I haven’t done a lick of work since that day.

MR. NIBLIS: (Shouting) Look, the van is here! It’s Ruth Buttress! Time to go, everybody! All aboard for Avalon!

MRS. VETCH: (Reaching for her things) Oh my goodness! Already?

MR. NIBLIS: Time to go! Ruth Buttress is here with all the latest news from Hell! All aboard! It’s roundup time! On to the slaughterhouse!

MRS VETCH: But I’m just not ready yet!

MR. MINGO: No, wait. Mr. Palfrey, your legs are better than mine. Would you mind taking a look out the window? To see if—

FERN: Here, I’ll go. (Goes to front window) There’s no van. Just that tan car with a man sitting in it.

MR. MINGO: I suspected as much. One of Mr. Niblis’s childish jokes. When he’s not brooding, he’s making a nuisance of himself, crying out false news bulletins.

MR. NIBLIS: (Shrugs, rolls another cigarette) Well, it’s something to do.

MRS. VETCH: He claims to be some kind of prophet.

MR. MINGO: One of the very minor prophets.

MRS. VETCH: He’s some kind of outdoor preacher. He’s not really ordained.

MR. NIBLIS: Correction. Ordained, but not ordained by man or by any corrupt institution of man. I am fully ordained in the Invisible Church, which is the only true church. We know who we are.

MRS. VETCH: That may be so, Mr. Niblis, but I would not feel at all easy in my mind, going away on my honeymoon, if you, had conducted the marriage service.

MR. PALFREY: But where is this Avalon anyway? I see that old fat gal on TV talking about it all the time.

FERN: “There’s always room for you—at Avalon.” That’s what she keeps saying.

MRS. VETCH: Yes, that’s Ruth Buttress. She’s the Matron of Avalon.

MR. NIBLIS: She’s a front for Dr. Lloyd Mole. A so-called doctor.

MRS. VETCH: “No waiting list ever,” she says. “On the Special Value Package.” I wonder how they manage that?

MR. PALFREY: But just where is the place?

MR. MINGO: It’s somewhere over there in the Chinkypin National Forest, deep in the woods. In that great swamp

called the Chinkypin Bottoms.

MR. NIBLIS: On Chinkypin Bayou. Far from prying eyes. They say it’s so dark in those woods that the owls fly in the daytime there, and the bats flit.

MR. MINGO: And the nighthawk, with his fine white throat.

MRS. VETCH: Itused to be a Boy Scout camp. Camp Chinkypin.

MR. NIBLIS: It was too rough for the Scouts. The Scouts couldn’t take it, so they’re shipping us over there.

FERN: Is it a nursing home or a retirement village or what?

MR. MINGO: A little of both, I think. An internment center, in any case. Some sort of terminal warehouse for old people. A place to languish and die.

MRS. VETCH: Duvall told me that some of the ladies are put up in their own little rose-bowered cottages at Avalon. But I wonder if that can apply to me—being on the Special Value Package.

MR. NIBLIS: Duvall doesn’t know the first thing about Avalon.

MR. PALFREY: There’s a lot of snakes in the Chinkypin Bottoms. I drove down there one time to buy some steel drums off a fellow and ever where you stepped there was another snake. Spreadin' adders, coach whips, copperheads, canebrake rattlers, blue racers, big rusty moccasins—ever kind of snake in the world. I stayed the night at that fellow’s house and you couldn’t sleep for the squirrels barking and the hogs bumping up against the floor. It come a shower of rain in the night and these big pine-rooter hogs, don’t you know, got up under the house and snorted and made a big hog commotion.

FERN: Wasn’t there something in the paper about Dr. Mole?

MR. MINGO: Oh yes, he’s been in and out of the news for years. You may be thinking about that business in Florida. His red-vinegar therapyand his controversial yeast injections.

MR. NIBLIS: The big Fungometrics scandal. That’s when they ran him out of Florida.

MR. MINGO: I think he sold babies at one time, too.

MR. NIBLIS: Little newborn babies, still red and puckered-up.

MR. PALFREY: The well water at that fellow’s house was brown. It had a sulfur smell to it and it tasted like alum. And the mosquitoes drove me crazy. I cleared out of there before daylight.

MR. NIBLIS: Without your steel drums?

MR. PALFREY: My drums was already loaded and tied down, Mr. Niblis.

MR. NIBLIS: That’s what Ramp did, too. He cleared out early. Before Ruth Buttress could get aholt of him.

MR. PALFREY: Maybe he’s already over there at Avalon.

MR. NIBLIS: Not him. He’s too smart. He got out while the getting was good. Ramp was smarter than us.

MRS. VETCH: (Sighing) It’s just so hard, making a change like this at my age.

MR. PALFREY: Well, I guess you’ll just have to make the best of it, won’t you? I don’t have to worry about that myself. You’ll never catch me in a place like Avalon. I raised my chirren up right and I have two loving homes to go to.

Pause.

MR. MINGO: You know, I’ve never told anyone this before, but he’s gone now and I can’t see that it will do any real harm. (Looking about, lowering voice in confidential manner) Mr. Ramp took food to his room.

MRS. VETCH: But we all took food to our rooms, Mr. Mingo!

MR. MINGO: Some more than others. Your little cans of red sockeye salmon did not escape my notice, Mrs. Vetch.

MRS. VETCH: But Miss Eula didn’t really mind! She never enforced that rule, as you well know! She winked at her own rule! My goodness,everybody did it! You could hear munching and smacking in every room! Even with the doors shut!

MR. MINGO: One night, I saw Mr. Ramp ducking into his room with a plate of finely chopped nuts. The kernels had been chopped to a uniform fineness. He tried to conceal that plate from me. I’m convinced he was keeping some small animal in his room.

MR. NIBLIS: Mingo thinks Ramp had a roomful of canary birds.

FERN: Wouldn’t you have heard them cheeping and warbling?

MR. MINGO: One or two birds, I suggested. I never said a roomful. I never said an aviary.

MR. NIBLIS: More likely it was just some pet mouse or spider or lizard, like these prisoners keep in their cells. Trying to teach a roach, you know, to sit up and beg.

MR. MINGO: I was particularly watchful of Mr. Ramp in those last days. I was on stakeout, you might say. Another week or two and I would have gotten to the bottom of that mystery.

MR. NIBLIS: Ramp was too clever for you.

Sound of thunder, followed by rain beating against glass. Fern goes to the front window and looks out, her hand shading her eyes.

FERN: Well, here it comes.

MR. PALFREY: Did you roll the windows up?

FERN: Yes.... Still no sign of Lenore.... That tan car is still out there.

MR. MINGO: With two men in it?

FERN: It looks like just one.

MR. MINGO: A state police detective. They come and go.

DUVALL: It’s a new one out there today.

MR. PALFREY: Keeping an eye on this honky-tonk.

MR. MINGO: No, it’s not that. They’re waiting for Prentice. It’s another stakeout. They know he’ll turn up sooner or later to see Kate. Where the nectar is, there will be the bee also. The first principle of the manhunt.

FERN: (Musing) Betrayed by their own love for each other.

MR. PALFREY: (Musing) He knew it was dumb but he just couldn’t stay away from his honky-tonk sweetheart.

Enter Delray, with his Daily Planner, a memorandum book. He marches directly to Mr. Palfrey.

DELRAY: This is not, repeat not, a honky-tonk. Will you people please stop using that term? Is that too much to ask?

MR. PALFREY: What is it then?

DELRAY: Delray’s New Moon is going to be a very smart supper club, sir, with a strict dress code, and a slender white candle on each table. How many times do I have to go through this? We’re not going to have louts in here clumping around in boots and hats, drinking beer out of cans. And we’re not going to have a disgusting mob of kids dancing to their stupid music. Everybody has the wrong idea.

FERN: I wouldn’t think there would be enough people around here to support a—

DELRAY: Excuse me, ma’am, you’re thinking local. My vision is national. Right out there, a mile away, is Interstate 30, one of the very busiest of cross-country thoroughfares. It’s the new Broadway of America. My highly select guests will be coming from far and wide. In one year’s time, this place will be as famous as that drugstore in South Dakota that tourists flock to. Thousands of people—civilized people—will plan their trips around an evening of dining and dancing at Delray’s New Moon. You’re going to see nightclub history made here. (Looking about proudly) I’m having it all done up in an oyster shade.

MR. NIBLIS: What was all that? What did Delray say?

MRS. VETCH: (Raising her voice) An oyster shade! He’s having it all done up in an oyster shade!

MR. MINGO: There’s an unknown man back there on the bed, Delray.

DELRAY: (Not listening, goes to Mrs. Vetch, takes her hand) Well, now, look at you! Don’t you look nice today, Mrs. Vetch! I just know you’re going to be crowned queen of hearts at Avalon!

MR. NIBLIS: The van is late, Delray.

DELRAY: What is this, Mr. Niblis? Drooping spirits? On the day of your big adventure?

MR. NIBLIS: Where is Ruth Buttress?

DELRAY: Ruth Buttress is on the way. She’ll be here any minute.

FERN: There’s a strange man back there lying on a bed. I didn’t want to touch him.

DELRAY: What bed?

MR. MINGO: In that alcove off the hall.

DELRAY: (Not listening, looking at his Daily Planner) I don’t know what you’re talking about.

MR. PALFREY: We can’t get Booger Red over there to look into it. He’s all wrapped up in his ball game.

DELRAY: Sir, there is no one named Booger Red employed at Delray’s New Moon, and there never will be.

On July 31, the Oxford American will be celebrating the 50th anniversay of the publication of Charles Portis’s first novel, Norwood, with an event in Little Rock. More details can be found here.