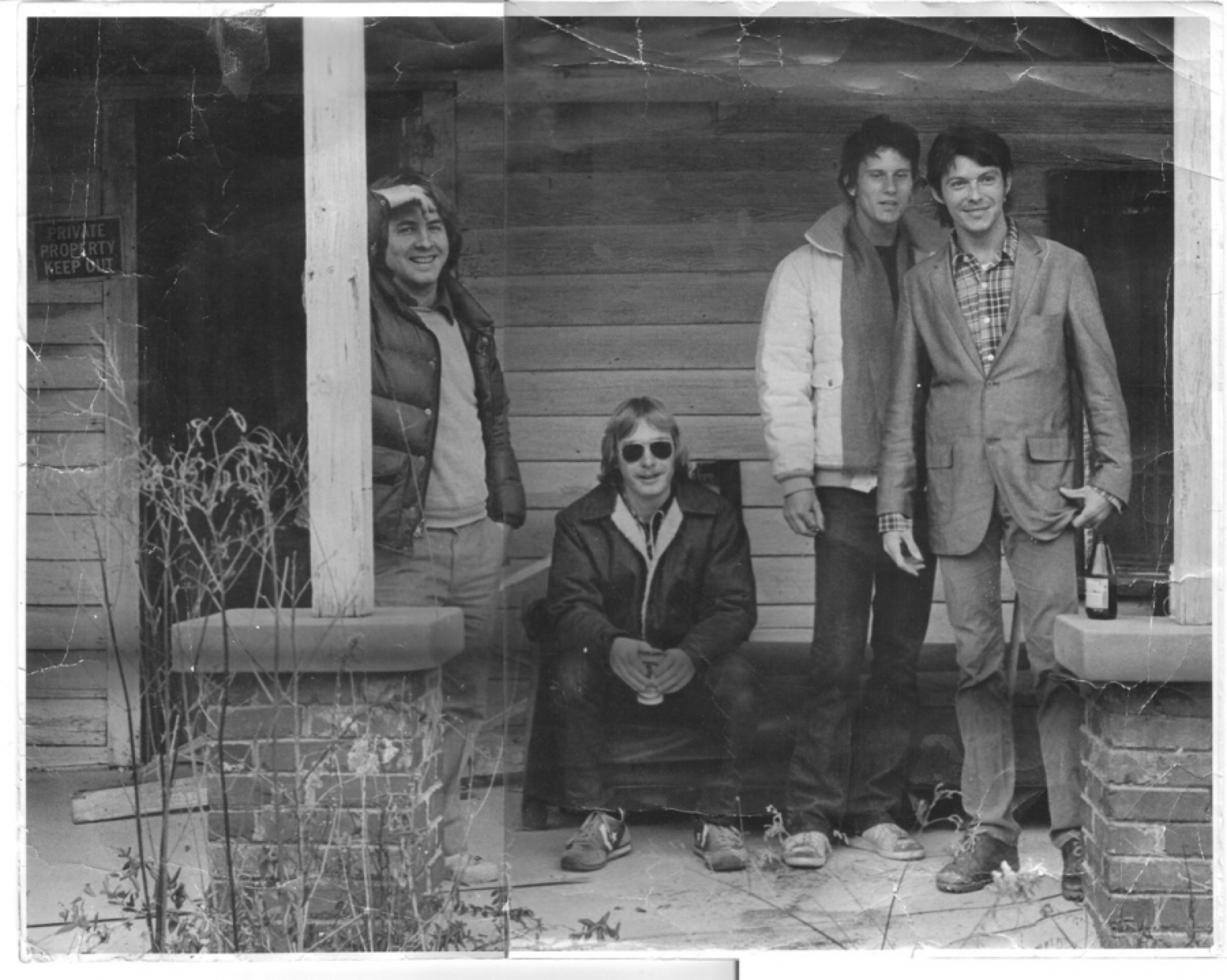

Photo by Tom Priddy. Courtesy of Laura and Gerald Duncan

"Down to the Graveyard"

By George Singleton

2019 Southern Music Issue Sampler featuring South Carolina

Track 3 – “Down to the Graveyard” by Moon Pie

If I heard someone talking about Moon Pie between the late 1970s and early ’80s in upstate South Carolina, I knew that it wasn’t a reference to the wondrous confection hailing from Chattanooga. Nope, they would have been talking about the best goddamn rock & roll band ever that hadn’t yet made it to the big time. I came to know this quartet from my college buddy Michael Hunt—now a theater professor in Virginia—a man one year older than me in age and forty years older in music and literature experience. “Come with me to see the best goddamn rock band ever that hasn’t yet made it—Moon Pie,” he said to me. He knew these guys, who were a few years older, because they all went to the same high school in Greenville. “I want to take you by the church to see them,” he said.

Of course, I thought, What? Had Michael converted to Protestantism without my knowing? I said, “Moon Pie. Really?” It sounded overly Southern to me. I imagined bands named RC Cola, Red Man Chewing Tobacco, Collard Greens. This was 1979. Already I’d jumped from the Grateful Dead to the Sex Pistols, the Clash, the Ramones, et al. And I’d somehow never cottoned to the stereotypical Southern rock bands of my time—though I loved the Allman Brothers, admired Marshall Tucker. And this Moon Pie band was from South Carolina! How good could they be, really? “What kind of music do they play?” I asked.

“Just shut the fuck up and come on,” Michael said. “They don’t sound like anybody.”

The lineup changed over the years, but the band I met and knew was Doug Whelchel on drums, Tommy Tate on bass, Lynn “Roy Moon” Rochester on lead guitar, and Gerald Duncan as the rhythm guitarist and lead singer. Dick Hodgin—who had one working eye, a source of self-deprecating jokes told by him—was the band’s sound man and manager and later produced a five-song EP by an unknown group named Hootie & the Blowfish. Dick might’ve been Rob Reiner’s influence to have the volume turned up to eleven in This Is Spinal Tap.

Gerald, clearly, fronted the band. He wrote most of the songs. His stage presence made John Malkovich and Richard Burton look like amateurs. As for the other members—and no offense to my friends—their stage presence didn’t look that much different than a small-town police lineup.

The “church” was “The Church of Rock ’n’ Roll,” as early local journalists labeled it, in downtown Greenville, on Townes Street. I never knew what happened to the original church and its flock, but whoever owned the building allowed these ne’er-do-wells to rent space for practice.

Michael and I walked in. He introduced me around, maybe told everyone that I was okay, not a narc. Understand that in 1979 I had decided that I might want to be a writer of sorts. I’d just returned from studying in France. Boy, did I know everything! Wouldn’t it be both charming and gracious for me to impart my wisdom, at age twenty-one, to these fellers in a band named after a lunch-box treat?! My god, these guys hadn’t even gone to college, unless you counted Gerald’s matriculation from Eastside High School—where he was student body president—to the Hank Thompson School of Country Music in Claremore, Oklahoma.

The Church of Rock ’n’ Roll attracted a bizarre mix of people, I thought at the time, groupies milling around right before Moon Pie went to the stage to work on songs they’d written the previous week, maybe “Two Girls in Love” or “Down to the Graveyard.” Maybe “Jenny,” about a young woman who “is a switchblade,” or “Regina,” which concerned an interracial relationship. The Moon Pie fanatics, as it turned out—people I thought were wannabe artists, writers, actors, comedians, musicians, professors, lawyers—actually thrived later (all of them, I can count them off) as artists, writers, actors, and so on.

The band started up. Within about thirty minutes I understood that Moon Pie, indeed, couldn’t be categorized. Nowadays I can say that they might’ve been at the forefront of Americana, or of cowpunk. They came across as a mix of Willie Nelson and Elvis Costello, of Buddy Rich and Graham Parker.

In clubs and bars they played ninety-minute shows, at the least, filled with three- to four-minute narratives about living in a town and wanting to get out, being away from home and wanting to return, hating a job, being unemployed and willing to work for the worst boss ever. Unrequited love. Main Street drag racing. Bad, bad radio station formats. Moon Pie was a mix of Springsteen, the Modern Lovers, Hank Williams, and the Blasters. Some years later I saw Jason and the Scorchers—a band I love—and thought, Moon Pie, back in the day.

Moon Pie dropped one EP, Welcome to Hard Times, but Gerald became disenchanted with Greenville’s live-music scene and moved to Raleigh. The band changed its name to the Accelerators and signed with Dolphin Records and then Profile, and toured the United States, playing New York City to Los Angeles, opening for the Clash and Nick Lowe. At some point, Rochester and Tate decided not to stay in the band. The lead guitar lineup changed a couple of times, as did the bass player. Eventually, Brad Rice—later with Son Volt and then Keith Urban—became the lead guitarist. Gerald remained the heartbeat and backbone, and despite the promising reviews of its albums, the label, after releasing Run-DMC’s first album, made a decision to fully embrace rap artists and take a new direction.

And that’s how a Greenville band that once called itself Moon Pie could’ve been, could’ve been, could’ve been.

Return to the South Carolina Issue liner notes.

Order the 21st Southern Music Issue & CD featuring South Carolina.