Peasant Food

Notes from a life in restaurants

By Brad Johnson

Untitled by Jen Everett. From the series Redoubled/Something We Carry

In 2013 in Venice, California, my business partner chef Govind Armstrong and I opened Willie Jane, a Low Country Southern restaurant named after my one-hundred-year-old aunt. The eldest and at the time only remaining sibling in my father’s family, Aunt Willie Jane and five of her siblings had been born in Dawson, Georgia. My dad, the youngest of the seven, was born in Hartford, Connecticut, after the family moved north in 1925. I felt a restaurant in my aunt’s name was a nice way to pay homage to my family’s Southern roots. The space, with its ample bar, cozy interior, and verdant patio, was the right backdrop for the dose of Southern comfort we aspired to deliver to Abbot Kinney Blvd., which GQ called the “Coolest Block in America” in 2012. Following up on my opening of Post & Beam in L.A.’s Baldwin Hills/Crenshaw neighborhood in 2012, Willie Jane provided a chance to pair an extensive Southern-inspired cocktail list with our Low Country menu. Head mixologist Derrick Bass created a cocktail program that he described as a “whiskey bar, with garden to glass influences.” Drinks were served in Mason jars and an all-day party on Kentucky Derby day featured our Derby Day Cooler, Coal Miner’s Daughter, and Mint Julep. Chef Armstrong described an “Edna Lewis–style” preparation of shrimp and grits, marrying his thoughtfully curated shrimp paste with stone-ground Anson Mills grits.

Much like a carefully choreographed Broadway play, for a restaurant to resonate, the moon and stars need to align. Access to sufficient capital is essential, as well as the financial discipline to eke out a profit from razor-thin margins. Does the décor speak to the guest as it is intended to? Does the menu appeal to a broad enough base? Will the kitchen and front of house coordinate the dance required to deliver the culinary experience that will have customers craving the food and raving about the service? Black restaurateurs learn that threading the needle requires a heightened sensitivity to circumstances that most other restaurateurs do not have to calculate. Those decisions affect profitability. Much Black culture, especially music, for instance, can be enjoyed with an iPhone and a pair of earbuds. Choosing to patronize a restaurant created by a Black restaurateur, a title not offered to me until late in my career, requires a different commitment.

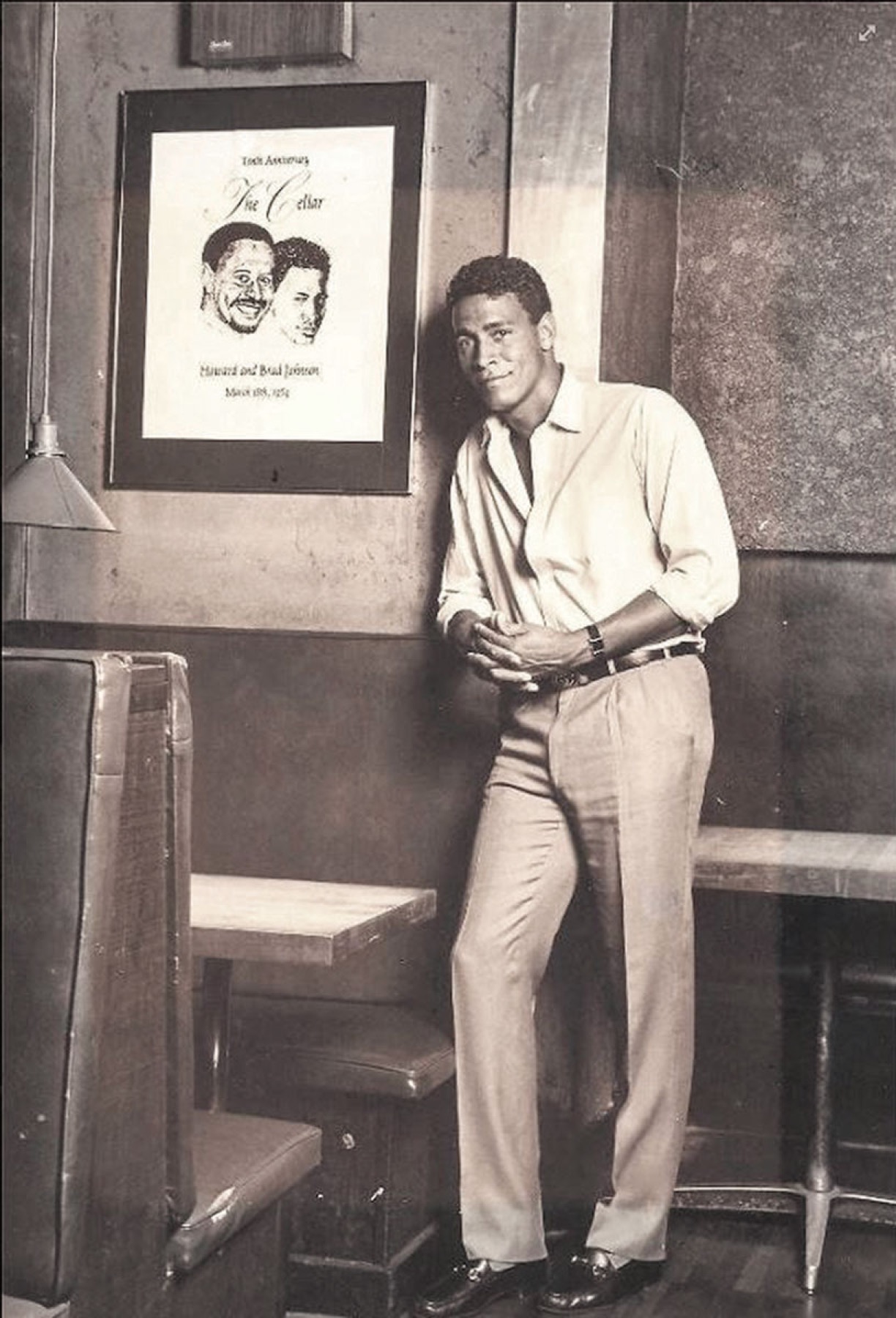

In February of 1993, our Georgia restaurant was set to make its debut on L.A.’s uber-cool Melrose Avenue. Located across the street from Spike’s Joint, filmmaker Spike Lee’s shop featuring his signature 40 Acres and a Mule gear, Georgia, reflecting a California take on Southern charm, marked a return to my restaurant roots. Prior to Georgia, I along with several partners opened the nightclub/restaurant/blues lounge Roxbury in West Hollywood after moving to Los Angeles from NYC in 1989. Washing dishes as a teen at my dad’s restaurant the Cellar, on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, was my introduction to the restaurant business, and I majored in Hotel, Restaurant and Travel Administration at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. During summer breaks from school and after college, I joined my dad assisting in operations at the Cellar. After my experience there, I was involved with opening several restaurants in Manhattan in the 1980s, including Memphis, Coastal, and 107 West, and I helped reconceptualize Nick Ashford and Valerie Simpson’s restaurant Twenty:Twenty, transforming the space from a two-hundred-twenty-seat restaurant and bar to a cabaret with live entertainment that included performances by Nina Simone and the Ohio Players. By the end of the decade I was ready for a change of scenery and some year-round sun. The West Coast was calling.

Georgia was a beauty: wide-planked mahogany floor; a palm leaf theme on hand-cut metal sconces and gold painted palm trees on burlap canvas; blood burgundy walls; hunter-green shadow-striped banquets; gold chargers. Floor-to-ceiling sliding-glass doors opened to a lushly landscaped patio. Investor group of actors and athletes and L.A. power brokers, check. Racially diverse staff, check. The Peach Bellini, concocted by mixology specialist and partner John Long, who also worked with me at Memphis and Roxbury, was to be our signature house cocktail. Wes Montgomery and Little Jimmy Scott softly serenading diners through hidden in-wall speakers enhanced the intended ambiance.

The anticipation for the opening of our restaurant was palpable. Tension along racial lines in the wake of civil unrest following the brutal beating of Rodney King in 1991 and the April 1992 acquittal of the officers who beat him still lingered in the spring of 1993. From my apartment in West Hollywood, I had watched the sporadic fires burning in South Los Angeles after the officers were found not guilty. Under the reign of Police Chief Daryl Gates, the LAPD had been a source of much controversy for its treatment of African Americans. When the trial failed to deliver justice in the eyes of African Americans, a segment of the Black community exploded in anger. Over five days, more than fifty people died, two thousand three hundred eighty-three were injured, and many businesses were destroyed. The image of Reginald Denny, a white truck driver, being pulled from his vehicle and assaulted, while one of his assailants, an African-American man, danced next to him as he lay in the street bleeding from the blow to his head, served to exacerbate the racial animosity. Despite the upheaval of the time, I was hopeful that our restaurant Georgia with its multi-racial staff and roster of celebrity partners and power brokers—including NBA great Norm Nixon, his wife Debbie Allen, Denzel Washington, music producer Lou Adler (the Beatles, the Mamas and the Papas), talent manager Sandy Gallin (Barbra Streisand, Neil Diamond), and Eddie Murphy—would send a message that racial cooperation and harmony could be achieved and celebrated.

During our pre-opening tastings, confidence in our chef, Jeanette Holley—whose experience included a stint as sous chef at Trumps in West Hollywood and running the kitchens at several other Los Angeles restaurants, a degree in nutrition, a broad ethnic heritage (Japanese and Black) coupled with a referral from soul food and culinary historian chef Joe Randall—was bolstered with each dish. Her version of Tasso ham bits served in rolled grits with a strand of collard greens in a creamy gravy; golden brown, perfectly crispy fried chicken; and spicy, peppered, grilled Gulf shrimp wowed our assembled group of investors. We presented a dual menu of traditional Southern classics alongside “contemporary dishes,” plates that would give some latitude to our chef and her pedigreed background. We highlighted soul food and Black culture, expanding the definition of “Black restaurant.”

At my dad’s restaurant the Cellar on New York City’s Upper West Side, I witnessed a successful menu that featured traditional soul food alongside Thai cuisine. In his autobiography written with Quincy Troupe, Miles Davis states that the Cellar featured “the best fried chicken in the world.” That fried chicken shared the menu with Thai beef salad and Chicken Gai Yang. Our chef, a man named Woo, emigrated from Thailand and trained under Thai chef Sam Poonpoolpoke, whose influence can be traced to several Upper West Side dining institutions such as Teachers and Teachers Too. Woo took over the stoves at the Cellar after our original chef, Leroy, quit. A talented chef working in a small hot kitchen, a scowling blur of sweat and brown skin, Leroy had an easily tripped temper. If a server was not in his kitchen the moment a plate was ready to be picked up, he would march into the dining room ready to do bodily harm. Woo came aboard and merged his Thai specialties with the existing mix of soul food and NYC period pub grub like French onion soup, chef’s salad, and shell steak.

My dad, Howard Johnson, purchased the Cellar in 1974 and quickly established it as one of the most popular nightspots for African Americans in the country. Having spent the early part of his career as the first Black clothing salesman at a downtown men’s store while working for the menswear company Paul Stuart, my dad, tall and handsome, was known for possessing great taste and impeccable style. Well read, quick-witted, and smooth as silk, he appeared on the 1960s show To Tell the Truth and fooled Kitty Carlisle into thinking he was Barney Hill, who had gained some notoriety for claiming he and his wife were abducted by aliens while driving through New Hampshire one evening in 1961. My father’s naturally engaging personality was well suited for his new business venture and for the clientele at the Cellar, which exemplified the popular “Black Is Beautiful” slogan of the day: celebrities like Arthur Ashe and Diahann Carroll; business titans J. Bruce Llewellyn and Ed Lewis; editors Marie Brown and Susan Taylor; musicians Phyllis Hyman and of course Miles Davis. In addition to the big names, for all kinds of Black folks in the city—judges, politicians, numbers bankers, post office workers, street legends, and teachers—the Cellar was a second home. Hosting both my dad’s contemporaries and their kids who were my friends, the Cellar crossed over generations. My childhood friend Attallah Shabazz often reminds me of how during high school at the U.N. International School, her mother Betty Shabazz would bring her to the Cellar after dance class to have a bite to eat before heading home.

Learning the business first hand, eventually working all front of house positions, gave me a glimpse into a glamorous world of fashion, music, food, and drink, all visible through the smoky cigarette haze of our tightly packed room. I also gained an appreciation for the important role each staff member plays in a restaurant and to this day make a point every shift to acknowledge all of them personally. At the Cellar there was no host at the front door. My dad and I oversaw the front of house, and his top rule was no matter what else you were doing, never lose sight of the door. He stressed the importance of greeting each person as they entered and saying thank you when they exited. Though places I’ve been involved with since sometimes have had a team of front door personnel, I’ve never taken my eye off the front door.

The Cellar was all of forty-six seats, with a low ceiling, long L-shaped bar, adjacent cocktail lounge, and small stage that often held more musicians than it was intended for. One of the best parts of my job was booking live entertainment. The Cellar became a hotbed for A&R executives to discover up-and-coming-musicians. Locally known r&b performers like Johnny Kemp, Keith Sweat, Meli’sa Morgan, and house favorite Platinum Hook were among the many talented performers who would blow the roof off a packed house at the Cellar until four a.m., Thursday through Sunday. In the kitchen, chef Woo and a cook would sweat over hot stoves until the last plate of fried chicken or Thai beef salad was served at three a.m. On Friday nights the dining room would turn four times. Those shifts were long; we’d count the night’s receipts and lock up, and by the time my head hit the pillow it was getting light outside.

My dad influenced every aspect of my life, from my chosen career to my love of the open road, Miles Davis, and the New York Times. Every Sunday while listening to jazz, I take a seat in the Eames chair he bought when I was five years old and read the Times, something I watched him do from New York City to Martha’s Vineyard over the course of his life. Our talks, whether on long drives up the Merritt Parkway, a gorgeous two-lane journey that is magnificent in the fall, or over grits, eggs, and biscuits at Perks in Harlem after tennis in Central Park, instilled the value of a strong father-son bond, one I’m grateful to now share with my son Bryce.

My lessons came from other places too. African-American culinary pioneer Alberta Wright, who owned and operated Jezebel in New York City from 1983 to 2007, became a second mom to me. Alberta told me that she reduced the size of the bar at her restaurant out of concern that a raucous bar crowd would scare away the white theater-going patrons who were essential to her business in the Theater District. She sacrificed the nightly profits generated from bar sales for what she calculated to be the long-term health of her dining room. I knew from experience at the Cellar, where the bar was lively and clientele almost exclusively Black, that our white neighbors were not patrons. That personal experience and what Alberta told me left an indelible impression on me. Believing we needed to be a successful dining room first, we limited the size of the bar to six stools at Georgia. Los Angeles had not had a restaurant like what we envisioned. Alberta’s soulfully elegant Jezebel was the model we thought most closely resembled what Georgia could be. Originally from South Carolina, Alberta chose an ambiance for Jezebel that featured crystal chandeliers, Warhol prints, African-American art, colorful shawls, hanging porch swings, and a house pianist. Its impressive wine list; Southern staples such as creamy, rich she-crab soup, honey fried chicken, and shrimp creole; and traditional sides like collard greens and macaroni and cheese commanded higher prices than at more traditional soul food restaurants that, since the mid-1940s, had become established across the country. Favorite venues like Leah Chase’s Dooky Chase (1941) in New Orleans; the Florida Avenue Grill (1944) in Washington, D.C.; Paschal’s (1947) in Atlanta; and Sylvia’s (1962) in Harlem offered comfort and meeting places for the Black community and safe havens for civil rights leaders during the turbulent ’60s. Dooky Chase became one of the first Black-owned tablecloth restaurants of the era when Leah Chase converted what had been a sandwich shop to a fine-dining destination. Serving her celebrated Creole specialty gumbo, Chase provided Black folks a rare upscale dining experience during the post–Jim Crow era, while white-owned restaurants were still off limits.

At Georgia, we were primed to make a splash. Through chef Joe Randall, I’d been in touch with one of the most celebrated purveyors of Southern cooking, Edna Lewis, who agreed to come to L.A. to refine our recipes and help train the kitchen staff. Having Edna’s blessing on the restaurant would be priceless. Visions of bread baskets holding flaky biscuits danced in my head, the ones that had contributed to Edna’s culinary reputation in New York in the ’40s at Café Nicholson, of which Truman Capote was a fan. I couldn’t wait to taste her corn pudding and legendary chocolate souffle, which, as legend has it, continued to rise while traveling from the kitchen to the table.

Although we only met over the phone, Edna was as warm and engaging as if we’d known one another for years. Edna was excited about our restaurant. She was happy that we were celebrating the South in Southern California. We chatted over several phone calls about how the dining room was shaping up and how we were hoping to evoke the charm and warmth conjured up by memories of the food our grandmothers served on Sunday after church. In her 1976 book, The Taste of Country Cooking, speaking of her Freetown, Virginia, roots, Edna writes, “And when we share again in gathering wild strawberries, canning, rendering lard, finding walnuts, picking persimmons, making fruitcake, I realize how much the bond that held us had to do with food.” I wanted Georgia to feel like that, a place where folks bonded over familiar plates.

Not wanting to fly, Edna planned to travel by train from her home in Virginia to Chicago, where I would meet her, accompanying her by train to L.A. In a lead-up to the opening, I attended a holiday party at the offices of the L.A. Times and mentioned my plans with Edna. At the time, I thought that it doesn’t get better than this. Unfortunately, Edna’s older sister passed away and the services were held the week she was scheduled to be in Los Angeles. Edna was very disappointed she wasn’t able to come and take part in the opening of Georgia. I was too, as I had so been looking forward to the long train ride with this incredible woman and culinary pioneer. Still hopeful, though, that at some point she’d make her way to L.A., we agreed to leave the possibility of a future visit on the table. Though we talked several times after the restaurant opened, regretfully Edna never made the trip.

As we opened our doors to welcome L.A., my right-hand man at the front desk, a native of Trinidad and former model and future restaurateur, Alvin Clayton, and I donned our trusty dark blazers, crisp white shirts, and slacks. The mahogany wide-planked floors glistened, polished to a supremely rich reddish-brown; one felt fancy just gliding across them. Our phone rang constantly, assistants calling for their entertainment-honcho bosses, whose self-perceived social status demanded they be first in the next hot dining room, seated at the best table. Black Los Angeles was ready to show itself; Georgia was the place it hadn’t known it had been waiting for.

Then it all began to unravel. Our kitchen was faltering: inconsistent at first and then, within a few weeks, failing badly. My business partner, Norm Nixon, the NBA All-Star who was born and raised in Macon, Georgia, and I knew we had a major problem. On a Sunday night, over dinner at the restaurant, we discussed what to do. I ordered the Sunday-night special of roast chicken with cornbread stuffing and giblet gravy, a dish that had been featured every Sunday at the Cellar. What I was certain would be a winner was inedible. After that grim discovery, I looked across the room and saw that Lionel Richie was also having the roast chicken. Norm and I understood that we needed to go to the kitchen to address chef Jeanette directly. We asked her to meet with us in the office. Before I was finished with my take on the version of the dish I’d just experienced, Jeanette turned to Norm and me and voiced her disdain for the “traditional” side of the menu, refusing to cook what she then called “peasant food.” Insulted and angry, Norm replied, “Peasant food! You’re talking about the food my grandmother and my mother cooked.” At that moment, I recalled how every Sunday when we visited my grandmother in Hartford, Connecticut, the native of Dawson, Georgia, prepared a huge platter of fried chicken, a pot of ham-hock-infused green beans, and potato salad, followed by a perfect sweet potato pie. A version of the fried chicken recipe has made an appearance at many of the restaurants I have been involved with. To this day, my cousins greet me during summer visits on Martha’s Vineyard with a plate of golden-brown deliciousness, piled high. Jeanette’s not recognizing the sanctity of these dishes as essential to our concept and legacy was unacceptable. Sensing there was an irreparable breach, she undid her apron and walked out.

With so much time passed since, I reached out to Jeanette to see if she wanted to offer her take on the experience. She took a few days to consider my request and wrote back this response to be included in this essay: “Before Georgia opened, Brad Johnson asked me if I was interested in going to Edna Lewis’ Southern Cooking Symposium in South Carolina. Of course I attended. It was a wonderful experience. I was excited for the opportunity to work on a project, bringing gourmet southern cuisine to Los Angeles. However, I realized that the menu was already decided on, and my struggle to input the endless pages of brilliant southern food ideas were all rejected. I felt that my purpose there was only to be a representation of a black person in the kitchen, a puppet. It was a one-dimensional menu and unfortunately I began to display anger, becoming difficult to work with. The experience was short lived. I never worked on a restaurant project again.

“That was nearly 30 years ago. In hindsight would I have acted differently? Absolutely! The restaurant was beautiful and uniquely offered a place for African Americans to gather, and enjoy food that represented the black culture. I wanted to participate in that process but then I was not mature enough to fight the constant debates.”

With Jeanette’s departure, suddenly, our much-anticipated restaurant, chef-less, was on life support. It was Joe Randall who stepped up to help. Joe is one of the most knowledgeable historians about the contribution of African Americans to the American culinary scene. Joe founded the Edna Lewis Foundation, now run by Savannah’s Mashama Bailey; owns and operates Chef Joe Randall’s Cooking School in Savannah; is an inductee in the African American Chefs Hall of Fame; and is an encyclopedia of culinary information. It was Chef Joe who had introduced me to Edna. With the situation critical at Georgia, I did not want to take any chances.

For extra insurance, I called my old friend Richard Hughes, chef and owner of the Pelican Club in New Orleans, now in its thirtieth year, to fly out to L.A. to add stability in the kitchen. In 1983 Richard and I worked together opening Memphis, the New Orleans–inspired restaurant in New York where I was a partner. He also helped conceive the menu and train the staff for the restaurant at Roxbury, where our top-selling entree was fried chicken and mashed potatoes. The popularity of these dishes proved to alleviate initial concern that club-going health-conscious Angelenos would shy away from comfort food. Richard is a phenomenal chef. His tender touch with crispy, spicy popcorn shrimp and his take on Cajun staples like okra maque choux and jambalaya are second to none. At Georgia, macaroni and cheese became the litmus test for the traditional side of the menu and proved a tricky one. We understood that we were competing against grandmothers. While there were many interpretations, the key was finding the right balance between gooiness and firm consistency, using sharp cheddar and not playing around with any obscure cheeses. That principle of honoring time-tested recipes was the ethos we knew we needed to stay with on the traditional side of the menu. Richard and chef Joe managed in short order to get our menu and kitchen crew on track but not before a couple of important food critics had their say.

The review by the L.A. Times food critic at the time, Ruth Reichl, was titled “Southern Discomfort,” which stung not just a little. While her critique of the early bumps we were experiencing with the food was fair (though interestingly, there was no reference to the opening chef, who managed to escape unscathed), my credibility was questioned especially relative to Edna, something I sensed followed me into future endeavors. I also felt the review completely missed the social implications and Georgia’s first-of-its-kind status. Another review that stands out in my memory unabashedly stated, “Maybe the best thing about Georgia is finally there is a black restaurant in an all-white neighborhood, eat those grits.” At the time, the absence of Black food journalists denied Georgia an opportunity for a review from a cultural perspective. Perhaps a Black food journalist would have celebrated Georgia from a contextual view that mainstream media only recently has begun to recognize. I recently reached out to Ruth Reichl, who, notwithstanding her long-ago review of Georgia, I have a great amount of respect for and whose writing I am a fan of, especially her reflections in her book Garlic and Sapphires. Having carried the hurt for so many years, I wanted to convey my thoughts about her review of Georgia in 1993. Ms. Reichl was very gracious and responded immediately, the result being a very pleasant exchange, allowing me to let go.

She wrote: “I’m stunned by the generosity of your letter. Why has it taken me so long to truly understand that racism is a white people problem?

“It’s terribly late for an apology, but I still want to offer you one. It was brave, and important, to open a restaurant like Georgia in the maelstrom of Los Angeles in the wake of Rodney King and the riots. And it still is. The good news, for all of us, is that I couldn’t write that review today. Things are changing. More importantly, there’s a new and diverse breed of food writers who recognize that recipes are more than merely ingredients, and restaurants are more than simply places to eat, and they’re starting to make their words matter.

“Thanks so much for reaching out with such largeness of spirit. The worst thing about being a writer is that your words come back to haunt you. It’s also the best thing about being a writer.”

Despite the less-than-kind initial press, Georgia became an important restaurant. We were able to get the food on track after the reboot with the help of our beloved chef Prince Atkins, who sadly passed away in 2019, and David Danhi. The room captured what we had hoped: it was elegant but not pretentious; soulful and lively. Each night was an exciting blend of people from all over along with no shortage of famous faces. Among our guests were Rosa Parks, Clint Eastwood, Sharon Stone, Magic Johnson, John F. Kennedy Jr., and Wesley Snipes, who would occasionally stuff biscuits into his pockets on his way to some Hollywood function. During a tumultuous decade in Los Angeles, many Black, white, and brown non-boldface-name diners embraced the restaurant as well. Barbara Fairchild, writing for Bon Appétit in 1994, and John Mariani, writing for Esquire in 1993, both selected Georgia as one of the country’s best new restaurants. Though these accolades were appreciated, somehow the reviews felt lacking in the telling of a fuller story.

What defines a “Black restaurant”? When in the mood for an Italian, French, or Japanese experience, the images, from service to food and décor, are easily conjured up. To begin to dissect what differentiates the Black restaurant, one must trace the roots of the culinary journey while examining the complicated relationship Black folks have with America as well as one another.

In 2016 a New York Times article titled “A Belle Époque for African-American Cooking” celebrated Black chefs and restaurateurs who had alleviated themselves from the confines of stereotypical expectations while still celebrating heritage and tradition. Jeff Gordinier wrote for the Times, “Across the country, a new generation of black chefs and cookbook authors has been reinventing, reinterpreting and reinvigorating what’s thought of as African-American food. Their work is part of the culinary development and self-discovery that has been going on for decades—centuries, really—but for anyone sampling their handiwork now, it’s clear that we’re in the middle of a belle époque.”

As a restaurateur, I appreciate the power of the media to shape a narrative. Clearly, a front-page feature in the coveted Times food section highlighting the culinary cultural evolution of African-American chefs and restaurateurs was heartening. While we were thrilled to be included and encouraged to see the Times elevate the story to front-page news, I also worried, with the lack of prominent Black food writers at major publications, this newfound inclusion would not sustain. For too long I’ve lamented the absence of Black food journalists whose take on the restaurants created by Black entrepreneurs might offer a bit more nuanced, deeper study. In 2020 we witnessed that day of reckoning for lack of inclusion in the food world come to pass at the James Beard Foundation, whose employees demanded more diversity in the organization, and at Bon Appétit, which in the wake of incidences of racial insensitivity, hired Dawn Davis, a Black publishing executive, as its new editor. A fuller picture of the African-American culinary journey will emerge as more outlets become more inclusive. Look no further than the Oxford American’s decision to have bestselling African-American author Alice Randall guest edit this important issue.

The history of African-American contribution to the culinary evolution of the United States predates the formation of these United States as we know them today. Soul food historian and author Adrian Miller wrote to me, as I was researching this topic: “In 1762, Samuel Fraunces began operating a popular dining establishment, ‘Fraunces Tavern,’ in New York City. While some dispute Fraunces’s racial identity, if he was of African descent, as some claim, that would make him one of the earliest known ‘Negro’ restaurateurs in America.” According to the Fraunces Tavern Museum website, Fraunces was known for “his cooking . . . notably the preparation of desserts. His cooking style was English. Meats were central to the 18th-century diet, and Fraunces advertised serving beef steak, mutton or pork chops, and veal cutlets as well as soup and the popular oysters—fried or pickled . . . a wide variety of desserts, such as cakes, tarts, jellies, syllabubs.” Around the turn of the century, Cato Alexander, a freed slave, became a well-regarded barman and chef, and around 1810 owner of his own tavern, known simply as Cato’s, in Manhattan at what today would be 54th Street and Second Avenue. His Southern specialties included fried chicken, and his South Carolina Milk Punch and Virginia Egg-Nog concoctions are among the earliest examples of the emergence of cocktail culture, contributing to the elevation of the practice from simply making drinks to mixology.

How was it that I did not know we were standing on the shoulders of trailblazers like Fraunces, Cato, renowned Richmond restaurateur John Dabney, and Tom Bullock? St. Louis bartender Bullock, whom I only recently discovered in Alice Randall’s novel Black Bottom Saints, is credited with having written the first cocktail book by an African American. Even as a career restaurateur, not until researching several projects with historical references, including this essay, had I ever heard of any of these pioneers. With more inclusive documentation, perhaps future generations of aspiring entrepreneurs will be inspired by their stories. I doubt my dad knew anything about the Black food-history figures in whose footsteps he was following. He acted on instinct. His decision to go into the restaurant business was the reason I chose Hotel, Restaurant and Travel Administration as my major and followed him into the business, not unlike the Dulan family in L.A., the Woods family in New York City, and Leah Chase’s family in New Orleans, all of us second generation, African-American restaurateurs.

After its 2013 opening, Willie Jane received from L.A. Weekly the accolade “Best Bar on Abbot Kinney.” The most popular item on the menu was shrimp and grits, the dish Los Angeles Times food critic Jonathan Gold called the best version in the city. After three and a half years, however, facing industry-related headwinds, a back of house labor shortage, and rising minimum wage, which increased pressure on the bottom line, coupled with the building we occupied winding toward approval for demolition to make way for a hotel, we sold the restaurant.

As for “peasant food,” it’s quite satisfying seeing those items now celebrated, and the recipes that have provided comfort at family gatherings and dinner tables featured on menus at restaurants operated by some of the world’s most renowned chefs. Equally rewarding is seeing Black chefs embrace with pride the food that has such a significant history for African Americans and being celebrated for doing so, while simultaneously infusing their unique spin on the familiar. Chef JJ Johnson in Harlem effectively uses a base of Southern staples like rice and grains on his Field Trip menu.

All these years and countless pulled-out chairs later, succeeding at bringing a diverse group of people together for a communal dining experience has been fulfilling. Providing jobs and a space for first dates, birthdays, marriage proposals, anniversaries, repast celebrations, and Oscar parties and having met such a wide range of people are the things I treasure most. I met my wife at Georgia. Even the slow nights had something to offer in learning the balance; as my dad would say, “Chicken one day, feathers the next.” Such valuable, simple statements guided my approach to hospitality, such as this from my dear friend the late Roscoe Lee Browne, who pulled my coat early with the gem, “Never mistake your arrival for the event.” At chef John Cleveland’s Post & Beam in Los Angeles, one could consume vegan “crab” cakes with black-eyed pea hummus and thoughtfully crafted cocktails like the Foxy Brown or If Beale Street Could Talk while being serenaded by the sounds of Gregory Porter, Gil Scott-Heron, and Nina Simone. Experiences like this, as well as those at many other trend-setting soulful places such as Seattle’s JuneBaby and Johno Morisano and Mashama Bailey’s the Grey in Savannah, are a testament to the cultural contribution of African-American chefs and restaurateurs to the American dining scene. Categorizing these restaurants, however, by ethnicity may prove elusive, as the essence of what defines them continues to evolve. An accurate and inclusive accounting of history, though, provides the connective tissue required for a better understanding of the American chapter in the African-American culinary story and for understanding that the journey is a continuum. I would like to thank Cato Alexander, Samuel Fraunces, Tom Bullock, Edna Lewis, Alberta Wright, Howard Johnson, Sylvia Woods, Leah Chase, Adolf Dulan, and countless others for the path they forged.