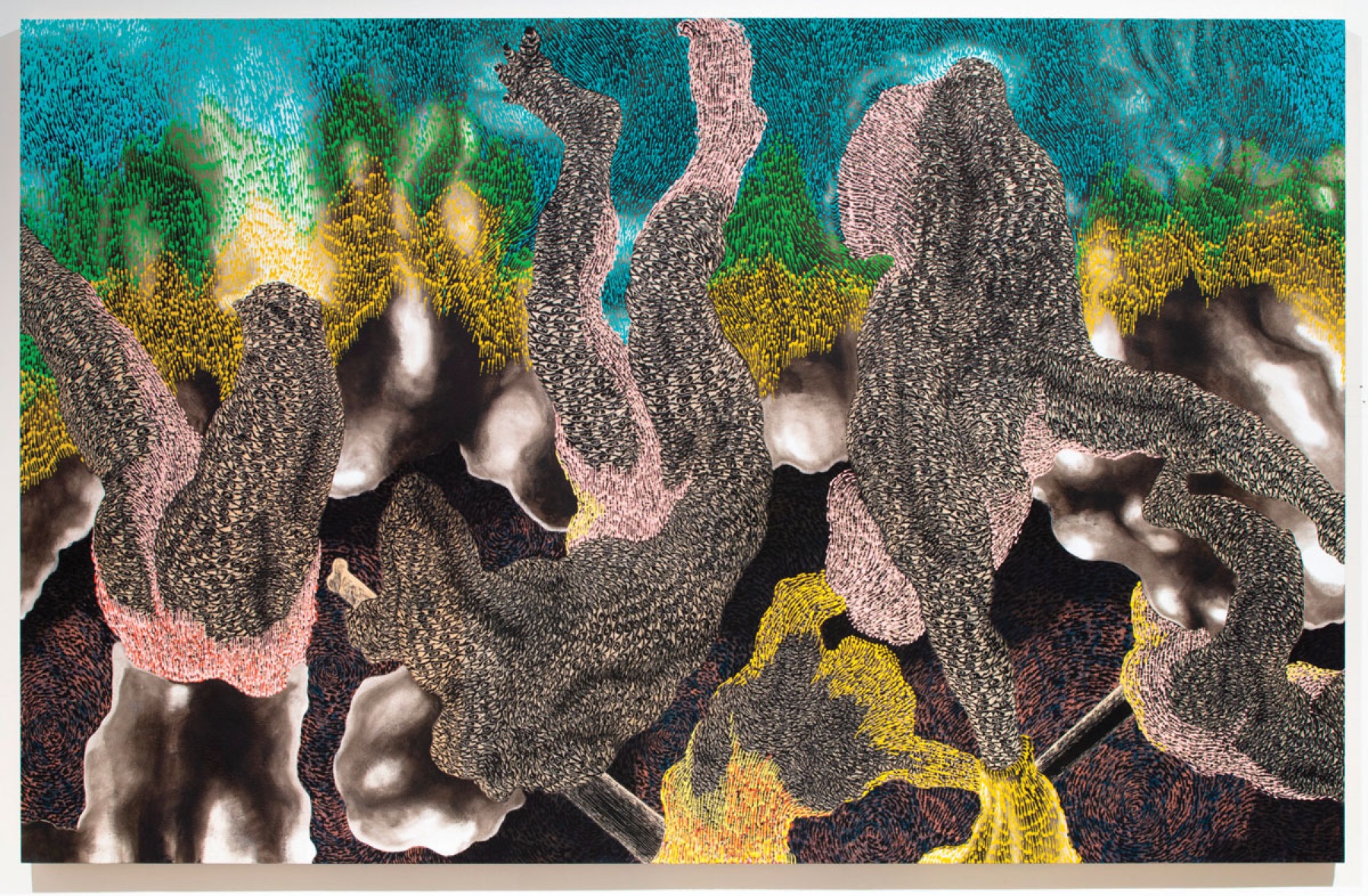

“Broken Skies: Nou poko fini” (We aren't done yet), 2019, by Didier William

Tarry with Me

Reclaiming Sweetness in an Anti-Black World

By Ashanté M. Reese

I set out what I needed for tea cakes: flour, buttermilk, Imperial sugar, vanilla extract, butter, and an egg. Measuring cups, mixing bowl, and hand mixer—double checking to make sure I had everything. I was nervous. Though many people had taken up baking as a way to work through pandemic anxieties, I was not one of them. I was making the tea cakes to add to an altar, but I was nervous about the offering. I had never built an altar to ancestors I did not know.

It wasn’t until I had pulled out all the ingredients, lining them up on the counter in such a way that I could clearly see Imperial’s signature dark blue crown stamped on the packaging, that I realized I had not decided where I would roll out the dough. That realization generated another: I also had not thought about how I would roll out the dough.

My mind wandered from my current home in the state capital to rural east Texas. There, I grew up daydreaming about Houston and its suburbs like Sugar Land, thinking they were the big city. They were places where one’s life could really be lived. I didn’t know then that we all—city and rural folk alike—lived in the long shadow of the plantation’s hold on shaping Black life. A mere three hours away, in Austin, I live a life of the mind: reading, studying, researching, and teaching. Sometimes that work keeps me from cooking, exercising, or making space for play. Growing up, the rhythm was different. Improvisation governed our lives.

Both thoughts—the where and the how—awakened memories in my body. My grandmother and my mother used their countertops as a workspace for rolling out dough. My grandmother rolled the dough with a mason jar or glass instead of a rolling pin. Each memory wove a thread between past and present. When I shared the memories with a friend, she remarked, “Yeah, my mom too. She said it rolls better that way.” These Black mothers across space and time made use of everyday materials to bring forth sweetness. I decided I would do the same.

The recipe, written by Mrs. Jones, is simple: 3 cups flour, 1 egg, 1 heaping teaspoon baking powder, 1 cup imperial sugar (emphasis in the original), scant 1/2 cup buttermilk, 3/4 cup butter, 1 level teaspoon baking soda, sifted fine, 1/2 teaspoon salt. Flavor to taste. I almost missed that “flavor to taste” meant baker’s choice for how much vanilla extract to use. Reading the recipe through for a second or third time reminded me that my grandmother always called vanilla extract “flavoring.” When Mrs. Jones wrote “flavor to taste” in her recipe, she extended an invitation to me to experiment, to trust (or at least honor) my own tastes. I don’t remember how much vanilla extract I added, and perhaps that is part of the experimentation too: letting every time be a little different, letting the day, the circumstances, the need inform the decision. This small detail reminds me that I am in the land of the living.

Nathan Pope was eighteen when he was convicted for burglary on November 29, 1879, and sentenced to five years. He was killed during an escape attempt two days after his arrival at what was known then as the Freeman prison camp—the location where the graves were uncovered. Jonathan Norton was twenty-seven, convicted for assault with the intent to murder and sentenced to five years. After seven months at the camp, he died of pneumonia. Esau Powell was convicted of theft in November 1875 and sentenced to six and a half years. He worked four years and two months before dying from chronic diarrhea in 1880.

Their graves were almost not found. The Fort Bend County Medical Examiner’s office concluded with ninety-nine percent certainty that the bone fragments discovered at the construction site for Fort Bend Independent School District’s James Reese Career and Technical Center on February 19, 2018, were not human. But Oscar Perez of the Fort Bend Independent School District wanted one hundred percent certainty before moving forward with construction. A forensic anthropologist at Sam Houston State University reported conclusively: the bone was human. To whom it belonged they did not know, but the single human bone led to the discovery of ninety-five graves and a reckoning for the town and the state.

Everywhere, they were called “The Sugar Land 95,” but I did not want to call them by the collective name that places more significance on the town than the people. Every utterance suggested they belonged more to Sugar Land than to themselves. When they were living, the state treated their labor as property, contracting them to work on plantations or for private companies. Now that they are dead, their bodies are treated as a single collective, evidence of a history that has been hidden in plain sight in the very soil on which the bustling suburb is built.

I wanted to know their names.

In September 2020, local and national news outlets announced that a newly published report included the names of those who occupied the graves. Trading my email and name for access via the Fort Bend Independent School District, I retrieved the report titled, “Back to Bondage: Forced Labor in Post Reconstruction Era Texas.” I looked first for the names. After a four-page spread acknowledging sixty individuals, two historical commissions, and the Fort Bend ISD school board for their part in conducting this study; after sections that explain the environmental and cultural context within which the graves were found; after archeological evidence detailing the perimeters of the dig; after an accounting of the methodology used for exhuming the bodies; after an attempt to historicize enslavement and convict leasing, or “the tragic history of the African Diaspora”; their names appear on page 254, buried in the middle of 535 pages.

They appear in charts, each life confined to a line item with nineteen entries: Convict Name, Convict Number, Age at Conviction, Height, Weight (lbs.), Color, Employment (Trade), Nativity (State/Country), Marital Status, Date Convicted, County of Conviction, Reason for Conviction, Sentence Length (Years), Received Penn., Last Camp of Residence, Death Date, Age at Death, Death Details, and a notes column to hold information that did not neatly fit into the others. Each life reduced to the equivalent of data entry in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet.

Esau Powell had a scar on his right knee, indicated the notes column. This mundane detail undid me.

I copy each name into a book that sits on the altar dedicated to Esau Powell, Jonathan Norton, Nathan Pope, and the other people buried at the camp. I am an anthropologist by training. It is my job to build relationships, to learn with and from Black communities to understand various aspects of our lives. When I am in the field, I spend most of my time listening to people who choose to share their time and stories with me. In Washington, D.C., I sat on well-worn front porches and danced the wobble on makeshift outdoor dance floors to learn about food access. In living rooms and kitchens in Baltimore, I listened to elders detail how they navigated everyday life with type 2 diabetes, allowing those who asked to pray or speak blessings over my life. I am good at my job because it brings together several things I value: community, Black people, storytelling, and listening. But how does one build relationships with the dead?

Ordinarily, I would hang out with people for months, having casual and formal conversations as I got to know a new place and new people. Absent of my usual ethnographer toolkit, the altar is an invitation to these ancestors. In fieldwork with the living, I wait for people to invite me into their homes and lives. In fieldwork with the dead, I’m inviting them into mine. The altar honors them, these men who would have worked anywhere from twelve- to sixteen-hour days with minimal food and little care except what they may have offered to each other. Building relationships with the dead is not only a practice of technical skill but a spiritual one.

My handwriting is terrible, but for recording the list of names, I slow the motion of writing as if each letter, each name undoes the violence of abstraction that the collective name “Sugar Land 95” commits. In official documents, in media, and in popular consciousness their lives and deaths are sutured to the town built on sugar production. Here, at least, I want to honor them by their names.

I am careful to abide with each while I write, as if the pauses restore their humanity. The list goes on, and so do I. Ninety-five people were buried in the cemetery between 1879 and 1909. So far, only seventy-two names have been identified. I refrain from writing “name unknown” twenty-three times. Their names were known to somebody. In a moment when we say the names of Black people killed by the police as ritual and remembrance, I grieve the loss of not feeling their names vibrate in the back of my throat.

Just as its name suggests, Sugar Land, Texas, was built on sugar. The Houston suburb was founded as a sugar plantation in the mid-1800s and developed into a company town supporting the Imperial sugar mill and later Imperial Sugar Company well into the twentieth century. Official histories tell a story of a town that was catapulted into modernity on the strength of good leadership and sugar cane production and refining. The people unearthed at the James Reese Career and Technical Center construction site force a different rendering of the town and company’s history—at the center of which is convict leasing, sugar, and Black labor as capital.

Between 1865 and 1868, Texas’s prison population nearly quadrupled, with the majority of the imprisoned being newly freed Black men and women. It wasn’t that formerly enslaved men and women were more prone to crime than their white counterparts, though state officials often made it clear that they believed Black people had neither the moral fortitude nor the intellectual aptitude to live completely free lives. Instead, in the aftermath of the Civil War, white Texans retaliated against their Black neighbors and kin through Black codes, violence (some five hundred black men and women were murdered between 1865 and 1868, almost all at the hands of white men), and imprisonment.

Texas, like other Southern states, turned to leasing both its limited prison facilities and those imprisoned to private companies as a means of solving its post–Civil War infrastructure and money problems. The state would contract with a company that would assume responsibility for all those imprisoned and subsequently sub-contract incarcerated workers to other companies. Early contracts, invested in projects thought to fuel the rapid post-war growth, were largely focused on the establishment of new industrial businesses and technologies. In 1878, Edward Cunningham and Littleberry Ellis entered into a five-year contract with the State of Texas, which granted them control of every convict and every penitentiary facility.

The longtime partners were an ideal choice for the state’s needs. In a deal intended to maintain stricter oversight of the prison population, the state leased every prisoner to Cunningham and Ellis for $3.01 a head per month. While sugar production had been in steady decline during and after the Civil War, Edward Cunningham established a stable, profitable sugar business, which included expanding his personal holdings to 20,000 acres and building a mill that could process 100,000 pounds of dry white sugar each day. His success earned him the nickname “The Sugar King.”

This would turn out to be the state’s most lucrative contract during the convict lease period, bringing in a net profit of more than $300,000 per year for the struggling state. From 1865 to 1880, the incarcerated population had grown by 1,500 percent. Black imprisonment had increased by five hundred percent compared to sixty percent for white people. In their biennial report in 1880, the directors of the Texas State Penitentiary wrote: “In Texas, as in nearly all the other southern states after the close of the war, on account of the rapid increase of population in prisons and the lack of prison accommodations, the working of convicts outside the walls became a necessity. . . . In 1874 and 1875, most of the convict labor was withdrawn from other outside industries and placed on farms.” At the close of 1880, the State of Texas had more than two thousand prisoners under its jurisdiction. Over half of them were leased to work on plantations in Fort Bend, Brazoria, Matagorda, and Wharton counties, otherwise known as the Sugar Bowl of Texas.

Working sun up to sun down—sometimes making additional treks to the fields that were more than a mile away—the work they performed was arduous. In the Texas summers, Robert Perkinson writes, “prisoners bewailed the heat and humidity . . . a man at work would almost gasp for breath.” Yet, Cunningham, Ellis, and penitentiary officials thought the mostly Black men and boys were biologically predisposed for it. Speaking about outdoor plantation labor, penitentiary superintendent Thomas Goree confidently remarked that “a large majority of [the prison population] have been raised on farms . . . having neither the capacity or inclination to learn a [skilled job trade].” Since white men were primarily assigned to work for railroad companies or housed in the sole penitentiary in Huntsville, it is clear that he meant the Black prison population. Those buried in the cemetery died from a variety of causes including many likely related to the work they performed. Seven died from pneumonia. Nine died from sun stroke. Eight died from malaria. And among those who did not die from extreme exposure to the heat, sun, and mosquitoes, ten were killed during escape attempts. The causes of death provide evidence for why the region gained the nickname Hellhole on the Brazos.

According to its official narrative, the dream of Imperial Sugar Company began in 1843 when two brothers built a sugar mill along Oyster Creek. That mill was later purchased by Isaac H. Kempner in partnership with William T. Eldridge in 1905, and Imperial Sugar Company was incorporated in 1907. The company’s official narrative tells a story of a beloved brand, known and trusted in Texas and the greater Southwest; the only sugar that “makes Grandma’s recipes right.”

The real history is more detailed and convoluted—one of entanglements of the state, private business, and carceral labor. In 1907, Cunningham sold his 5,235-acre plantation and his sugar company to the Kempner family in Galveston, who later transferred the title to Imperial Sugar Company. Under the leadership of I. H. Kempner, Dan Kempner, and W. T. Eldridge, Imperial shifted its focus to milling and refining rather than growing sugar cane itself. Isaac Kempner was opposed to using convict labor on the farm, though Alfred Davis and Isreal Newsom, the last two people buried in the unmarked cemetery, worked in Imperial Sugar Company’s refinery in 1911—one year before each of them died. The sugar cane industry in Texas had been declining. Between 1910 and 1920, acreage in sugar cane had fallen by forty-six percent. Some blamed it on the end of convict leasing, others on a series of weather-related disasters. In any case, the drop in cane production meant the company needed to not only shift its priorities but also build a recognizable brand that would garner loyalty in the U.S. South. This shift included building a company town that would attract laborers. It sold the 5,235-acre plantation purchased from Edward Cunningham to the state for $50,000 less than what it paid for it in exchange for an exclusive contract in which the state agreed to sell its cane to the company.

The property included everything the state needed as it shifted to managing its own farm operations: a sugar house and mill, boilers, engines, machinery, plants, commissary, warehouse, railroad and tramroads, rail and tram cars, locomotives, harnesses, mules, horses, cattle, hogs, other livestock, crops, merchandise, supplies, and housing for 250 convicts and guards. It also included unmarked graves. By the time the property was sold to the state, Nathan Pope, uncovered at the James Reese Career and Technical Center construction site, had been buried there for nearly thirty years. It would be another 112 years before we learned his name.

By 1990, Imperial Sugar Company was a Fortune 500 company and one of the largest sugar refineries in the U.S., but that growth took time—building the infrastructure for a company town, a stable labor force, and intense branding—to put the company on a path toward success. As part of its branding, the company produced and distributed free cookbooks as early as 1915. The Household Economist—part budget worksheets, part handy go-to for measurements and cooking times, part recipe book—bore the following tagline on its cover: “Reduce the high cost of living by securing the very best grade of sugar your money can buy.” The 1920 cookbook, a compilation of recipes from members of the Parent-Teachers Association of Sugar Land, is titled, A Barrel Full of Imperial Recipes. From it, I chose Mrs. Jones’s recipe for tea cakes.

I often return to a black-and-white photo of my mother’s hands. In it, she is using a can to roll out dough on her countertop. She is making tea cakes for me, something she had done many times, but especially so in my adult life. These tea cakes—or rather, my mother’s preparation of them—kept us tethered to each other through every move I made, from Texas to Georgia to D.C. to Tennessee and a handful of other places before returning, through my stints with veganism, through the class- and world-straddling my work and life have required. When I was away, my mother mailed them to me and friends, a form of labor I associate with love.

On the day I took the photo, I watched her make these tea cakes for me, understanding the act to be something more than baking. An offering. So when my eyes landed on the words “tea cake” in the 1920s cookbook, I was both surprised and delighted. It felt like an invitation. I knew what the first sweet offering on the altar would be; I would make this offering not for the living but for the dead. When the baking was finished and the tea cakes had cooled, I took the first six, prayed over them, placed them in a bowl, and nervously set them on the altar. The others, I divided into three Ziploc bags—one for myself and the others for two friends. When our graduate student successfully defended her dissertation proposal, my colleague Hi‘ilei sent a text that said, “Celebrating Mónica with a tea cake!!!” Then I knew. Life and death, mourning and celebration, past and present—an offering to the dead is also an offering to the living.

In biblical traditions I grew up with, altar building is akin to sacrifice. The first thing Noah did when he stepped off the ark after God’s 150-day vengeful cleaning of the earth was build an altar and offer a sacrifice to God to honor and give thanks for being spared. But my mother’s labor reminds me that there are other ways to build altars, to build worlds. There is no flood and no ark. There is no newly cleaned earth. There is only a world ravaged by capitalism and exploitation and experiments in creating anew.

Men and women working in prison camps during the convict leasing era would have been denied tea cakes or anything that resembled a luxury. To the extent that the state’s appointed prison officials cared about their well-being, it was to ensure that they were healthy enough to work, attend church services, and pay their penance for whatever they were convicted of.

State-appointed committees composed of white men investigated the treatment of prisoners. These investigations were centered on physical punishment or abuse, but prisoners themselves often interrupted these lines of questioning during official interviews to bring attention to how poorly they were fed. In the middle of testifying about receiving twenty lashes on one occasion and being hung on chains for seven hours on another, Henry Barsco declared, “What we are getting to eat is not fit for a dog to eat.” Other prisoners shared stories about leftover food scraped from individual plates, combined into one pot, and reheated for the next day’s meals. They were denied sugar or cream for their oatmeal and coffee at breakfast, if they received either. To have a bit of the sweetness upon which modernity and empire were built, they would have had to steal it. Can it even be called stealing? What do you name the process by which one takes back or keeps what was produced by one’s stolen labor? Reclamation, perhaps.

“Broken Skies: Ouve pot la pou yo” (Open the door for them), 2019, by Didier William

The living and the dead always meet, always cohabitate, always make beauty in their contrast.

In my understanding and practice of altar building, we build them to maintain relationships with ancestors. We offer them their favorite things: a cigar, a Bible, a piece of clothing. We offer them beautiful things: flowers, dirt from the earth, perfumes. We offer them our time and attention.

Nathan, Jonathan, and Esau’s altar sits on a small wooden side table that I painted green some years back, underneath a shelf with a plant, two candles, and a picture of my younger sister and me. I have draped a piece of kente cloth along the center. In the center of the cloth is the book that holds the names I know, blank pages to hold the names that I do not and may never know, and a prayer for and to them all. To its left is a bowl for sweet offerings. Right now, it holds the tea cakes. Next week, perhaps there will be something different. A tiny saucer to the right holds a mixture of sand from a place where the sea meets the shore in Bahia, Brazil, and red dirt from east Texas, two places culturally and geographically connected by the transatlantic slave trade and ongoing experimentations in freedom. It made sense to me to mix them, an acknowledgement of the global nature of sugar’s reach and a tribute to the lives shaped and cut short by it. A bouquet of dried flowers sits just underneath the tendrils of the pothos plant above—a reminder that the living and the dead always meet, always cohabitate, always make beauty in their contrast.

Since I do not know their favorite things, I add elements to represent items they may have been denied or had a hard time accessing. I use scraps of fabric to sew pillows. I whisper, Ancestors, I wish you sweet, soft rest. I lay a clean shirt that bears no stripes just beneath the book that holds their names. Ancestors, I wish you the dignity of clean and plentiful clothing to wear. And I offer a crudely painted piece of art. Ancestors, I wish you wonder, curiosity, and play.

In the archives I find ledgers that reveal exchanges between the state and Imperial Sugar Company, reports that detail abuse and resistance on prison farms, deeds that transfer plantations from private owners to the state. From these archival scraps, I piece together a history of the violent systems under which these men and boys died. But there are other ways of learning and knowing. Baking tea cakes for this altar was the first of what may be my many embodied experiments in exploring sweetness in an anti-Black world.

When I add the names of the men and boys to the altar, I ask for permission to explore their lives. I ask that they bless this ongoing work, and I invite them to tarry with me as long as they see fit. In exchange, I promise to prepare a place for them. Here, their lives and bodies will not be sacrificed on the altar of capitalism.

The men and boys whose graves were uncovered are a link along a continuum of freedom and unfreedom. Their lives and work are nestled within a larger context of colonialism, plantations, and growing global dependence on sugar. Their labor back then tethers us in the present to carceral structures that supported the growth of companies like Imperial Sugar Company and the development of cities like Sugar Land. These pasts have mapped a way toward the present, where carceral structures are part of our everyday lives through consumption. Futures are yet to be determined.

If there are to be different futures, they must be imagined and embodied. In Freedom Dreams, Robin D. G. Kelley writes that “a map to a new world is in the imagination.” Perhaps, too, that map is collaborative, constructed across time and space with the living and the dead. It is almost certainly the result of improvisations, or the complex and varied ways Black people navigate state violence. When we improvise, we create. We make something out of whatever is available. Sometimes, we make something out of nothing.

Here, at this altar, I take scraps from the archive and piece them together with a recipe from a company that exploited lives and labor, memories from within my own body, and a prayer. This is my offering. It is my promise to defend the dead and to fight against our collective demise. It is my contribution toward an improvised freedom.