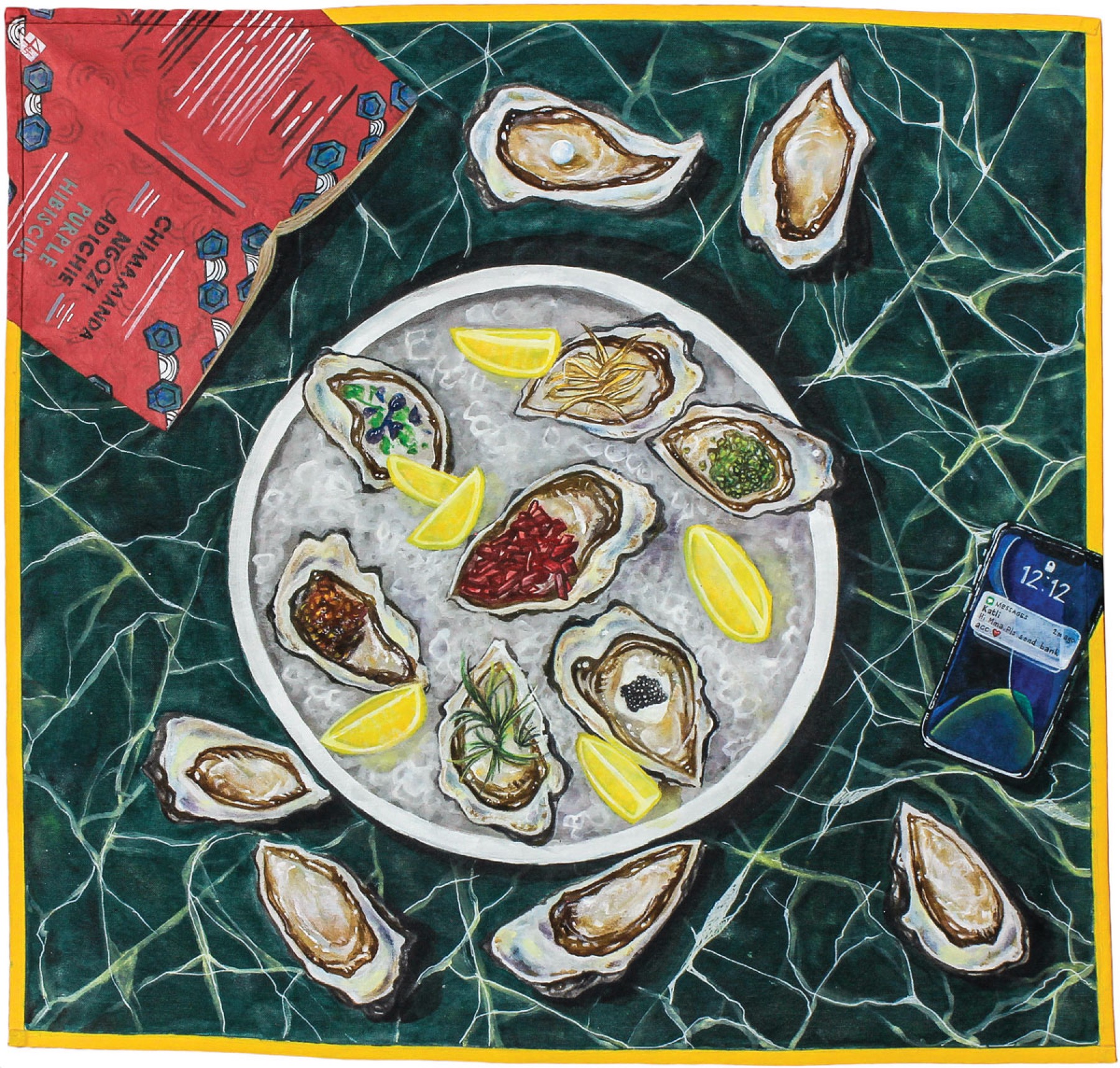

Oysters for boMa, 2020, acrylic, oil, pastel, and ink on canvas, by Katlego Tlabela. Courtesy the artist and Ross-Sutton Gallery

Oysters on the May

By Max Ufberg

Standing at the end of an oak-lined street, on a wharf on the banks of the May River, the squat, tumbledown white-brick building that is Bluffton Oyster Co. is abuzz with the thwack of knives against shells of varying shapes and fortitudes. Under the gaze of a line of pining South Carolinians, a small assembly of workers expertly slices and pokes a mass of coastal treasures: blue crab, wahoo, salmon, scallops, clams, mussels, and, of course, oysters. The walls are covered in a hodgepodge of souvenir hats, homemade wooden crosses, and other tchotchkes; outside, a 75-foot trawler called Daddy’s Girls is docked, casting an imposing shadow over the whole place. You’d never know the scene was a living testament to a dying tradition: the last remaining hand-shucking house in the state, where the creatures are plucked straight from the water and sold on the spot, the seafood version of farm-to-table.

For a time, oysters were everything in Bluffton, a tranquil Low Country town about seven miles west of its more famous sibling, Hilton Head. Until the 1930s, a number of so-called oyster factories dotted the landscape. But the trade couldn’t survive a series of setbacks, including a budding tourism industry, skyrocketing waterfront prices, a dwindling oyster supply, and a national typhoid scare that soured people on mollusks.

Though it’s changed hands a few times in its 122 years, Bluffton Oyster Co. never closed up shop, and it now stands among the oldest businesses in the state. “Some of the people that work at the oyster factory are seventy-five, eighty years old, and that's what they did since they were kids,” says Larry Toomer, a silver-haired and hale sixty-two-year-old who, along with his wife Tina, owns the Oyster Co. “They're preserving that culture, that way of life.” (Yet that preservation only extends so far: While the Oyster Co. owners speak reverently about the reclaimed land on which the building sits, grounds that have been buttressed using discarded shells from preceding shucking operations, details about the enterprise’s originators are surprisingly scant. All we can really say, based on city records, is that the business was owned in the early 1900s by Clarence “Buster” Martin, a native South Carolinian who served in the state legislature and the U.S. Department of Commerce.)

Toomer’s cause is an especially virtuous one, given how quickly the Bluffton of his youth—a square-mile town that writer Pat Conroy once praised for its “matchless serenity”—is being transformed by upscale housing complexes and buzzy restaurants. Bluffton’s population swelled by 92 percent between 2010 and 2020, from about 13,000 residents to more than 25,000; the town and its surrounding Beaufort County rank among the fastest-growing regions in the U.S. thanks in large part to sun-seeking Northern retirees on the hunt for a more economical alternative to Hilton Head.

That development has left ecological scars, particularly on the river that’s been so central to life here. The destruction of green space and a network of overburdened septic tanks have taken away a natural ecosystem to absorb the rainwater; without it, the water is running directly into the May, where it drops the salinity and creates an environment ripe for fecal coliform bacteria, which poses a threat to local marine life. In 2019, researchers at the University of South Carolina Beaufort found that fecal coliform levels were about fifteen times higher in 2017 than they were in 1999. For local fishers, the presence of fecal coliform has prompted a series of river closures over the years, meaning Toomer sometimes finds himself unable to fish from the land he’s leased from the state.

“We can’t have pollutants going in and degrading the quality,” Toomer says. He cares about the issue deeply, for obvious reasons. It’s actually what motivated him to get involved in the town council, on which he’s served since 2012. “I want to make sure we preserve our natural resources for generations to come.” To that end, he’s helped spearhead a number of bureaucratic blueprints to benefit the May, most notably to him the $2.6 million plan to transition a majority of the town to a more modern sanitary sewer system. “Will that be enough to open those closed areas? I don't know,” he says. “At least it won’t get worse once all the new developments are on sanitary sewer.”

As Toomer speaks to me about bacteria levels and sewer systems, I realize there’s possibly nobody around who better encapsulates the town’s evolution. Here is a man who grew up in the region, whose father and grandfather operated oyster outfits of their own (“The first thing I ever remember was being in an oyster factory”), and who was out on fishing boats by the time he was eight years old. At thirteen, Toomer was running his own crab boat; he was thirty-four when he bought the Bluffton Oyster Co. from its previous owners. He’s kept the building’s ramshackle charm intact and is a fierce local advocate for watershed restoration. At one point he tells me, “I can close my eyes and draw a map of every creek, every river around.” And in that moment he flashes his widest grin.

Toomer’s reverence for the water hasn't precluded his more entrepreneurial ambitions. He expanded the Oyster Co. to include a restaurant and a catering arm. (Three of his five children continue to work in the family business.) The Toomers live in a stylish home with a spacious front porch and a tin roof that accents the otherwise white exterior, a few blocks from the oyster factory. They’ve certainly benefited from this new, frenzied Bluffton.

That’s not to say Larry Toomer is living an easy life. He’s still out on the boat, sometimes five or six days a week, scouring the thirty acres of river he’s leased. But when he tells me he’d prefer the company of his boat—“I’d rather deal with Mother Nature than human nature any day”—I’m not sure I believe him. His business has become a local landmark. Just a few days before we spoke, the clothing company Carhartt had come to stage a photoshoot for an ad campaign, for which they used members of Toomer’s family as models. And this is not an altogether unusual occurrence. “My shrimp boat is the most photogenic boat in this part of the country,” he says. “I guarantee you, you'll see it all over the place.” This does not sound like someone who’d prefer a Cast Away–style life of marshlands solitude. To me, it is clear that Larry Toomer loves Bluffton, wants to see it grow—and to survive. And Bluffton, for its part, seems to love Larry Toomer.