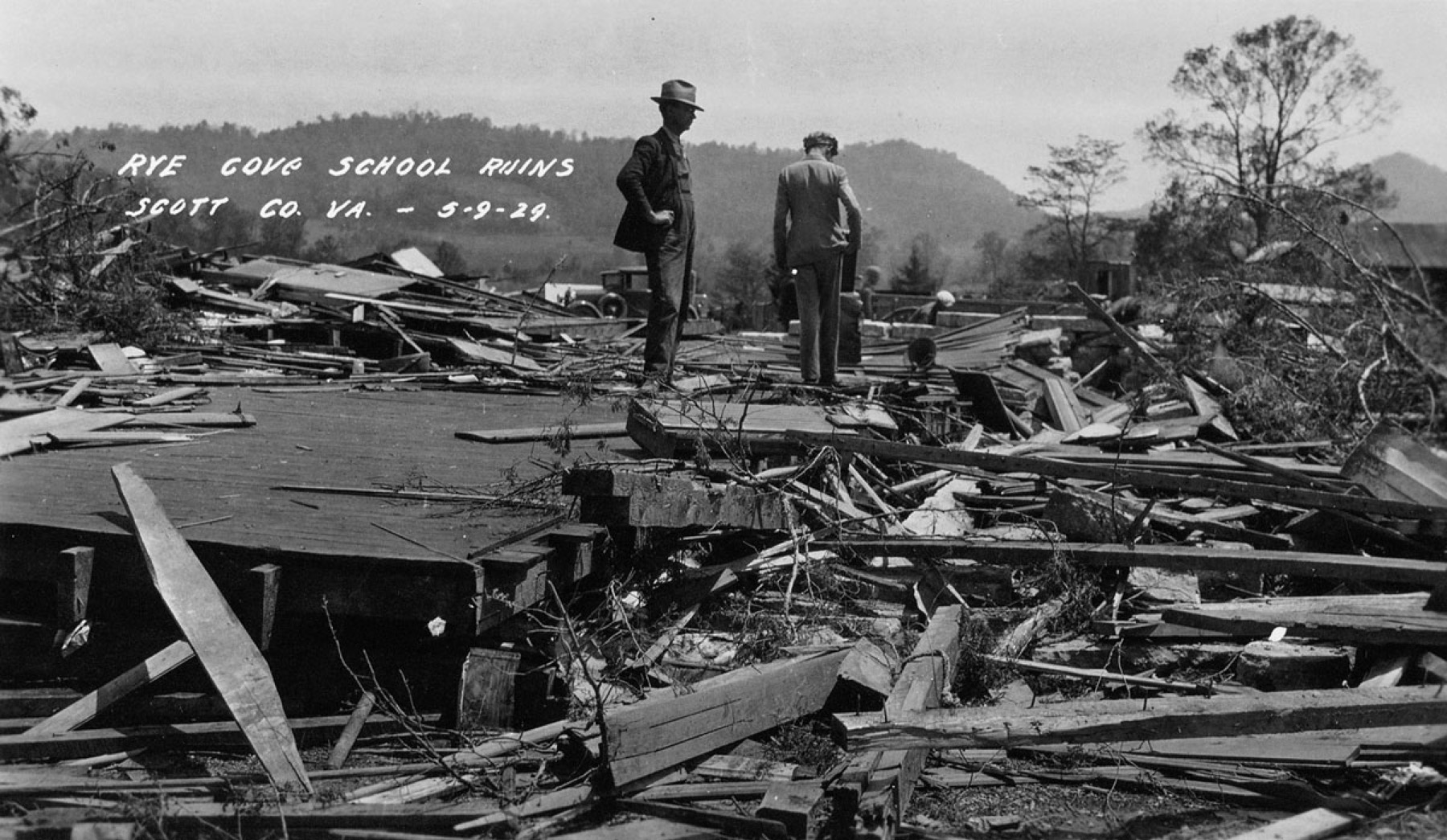

Destruction caused by the Rye Cove cyclone, the deadliest tornado in Virginia history. Photo by the State Department of Education. Courtesy the Library of Virginia

The Cyclone of Rye Cove

By Amy D. Clark

My grandfather kept the Victrola in his woodshop, where it stood for years, covered in the sawdust that snowed from his worktable. I’m not sure why he kept it there, except that his house was small and already crowded with old things. Meaningful things.

The talking machine, as early phonographs were called, had belonged to his aunts, never-married sisters who lived in a little house on a dirt road near our own houses along Long Hollow, Virginia. Inside its cupboard was a treasure trove of 78 rpm shellac records in their original sleeves and a rusty can of needles. The records speak to the range of music they loved, from Jimmie Rodgers to Doc Watson, and the deep scratches in some of them signal which ones they played most often.

When grandkids were around—on snow days, for instance, when school was out and Poppy couldn’t work outside—he would insert the crank and wind the spring motor, which made the turntable spin. Then, he’d lift the heavy tonearm and carefully position the needle on the record. The lonesome sounds of guitars and mandolins, blended with the high, crooning voices wafting from the speaker box, had the power to send us back in time to the sisters’ 1920s dark, cozy house with its low ceilings, a fire casting shadows on the walls.

The talking machine sat in his woodshop until my husband and I bought our first house, a 1936 federal with original woodwork and tall ceilings that felt hollow with the little furniture we owned. He decided it would look better there, where a previous Victrola might have stood not far from the telephone cupboard built into the stairwell. As the years passed, the Victrola was like an elder in our home, overseeing the growth of our family. We opened the lid to let our children peek inside, and taught them how it functioned, just as Poppy had taught us.

Riley and Landon, now in middle school, have since begun learning the banjo and guitar, even playing with their music classes at our local Gathering in the Gap festival where artists like Marty Stuart, Dave Eggar, and Steep Canyon Rangers have performed over the years just yards from our front yard, singing some of the same songs that are tucked into the Victrola’s cupboard.

Several years after Poppy’s passing, I called in an expert, Corbin Hayslett, a former student of mine and acoustic artist who had recorded on the Orthophonic Joy album project, the collection re-creating songs from the 1927 Bristol sessions, where the Carter Family’s career began. Hayslett was a graduate student at the time in East Tennessee State University’s bluegrass music program. He demonstrated how to clean and index the records as he told stories about the artists and songs. We found that the sisters had particularly enjoyed the Carter Family’s music, collecting many of their records, such as “Wildwood Flower” and “Keep on the Sunny Side.” But there were two copies of one particular record, which seemed odd—two copies of a song A. P. Carter had written after one of the most tragic days in Virginia’s history, “The Cyclone of Rye Cove.”

By May of 1929, A. P. Carter, his wife, Sara, and her cousin Maybelle were well into their recording careers. Their popularity had grown nationwide in a robust, pre-Depression economy that gave folks the cash to splurge on records. In the years since 1927, when they first piled into A. P.’s car and traveled over pocked and ruddy roads to audition for Ralph Peer of the Victor Talking Machine Company in the now-legendary Bristol sessions, the Carter Family’s records had sold in the hundreds of thousands.

But the industry was hungry for more songs. Though their recording contract and income gave them the means to relocate, the Carters had decided to stay in their home community of Hiltons, Virginia, where ballads and Appalachian mountain tunes were plentiful. According to the book Will You Miss Me When I’m Gone?: The Carter Family & Their Legacy in American Music, A. P. traveled around the region collecting songs and bringing them back to the studio, where the trio carved each song down to the required three minutes for recording. “Mother” Maybelle (mother to the legendary June Carter Cash) played her famous “scratch” on her guitar, her signature flatpicking style that is credited for being the foundation of bluegrass music. She and Sara, playing the autoharp, sang with A. P. (in his words) “bassing in” from time to time. Demand was such that they sometimes recorded a staggering twenty songs in one session. By March of 1929, two months before the tragedy that would inspire A. P.’s ballad, the Carters had recorded a dozen more.

Mountain children grow up hearing that tornadoes are rare because they can’t traverse the hills as well as they can the plains. But on May 2, 1929, a clutch of funnel clouds descended like needles on records, cutting grooves along the mountain chain and into the Gulf Coast. Over a hundred people were injured or killed in Tennessee, West Virginia, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Florida, and Rye Cove, Virginia, just thirty miles away from the Carters’ home in Hiltons.

As the lunch hour drew to a close and a light rain fell, children were still playing outside around the Rye Cove School, which included one hundred fifty-five students and eight teachers in a rural Scott County, Virginia, community. In 1970, a student in ETSU’s Master of Arts program named Frances Frye Reed conducted interviews with survivors and collected eyewitness accounts as told to local newspaper reporters in the days following the storm. Observers and survivors described an ominous dark cloud that appeared over the mountain, blowing toward the school by winds that bent trees. The howling funnel cloud tore over the mountain, grinding its way across a pasture toward the school. Schoolchildren recalled running to seek safety in the building, but the force of the wind peeled away the school’s roof and pulled at the structure. When the frame of the school collapsed, it tipped the wood stove into the rubble, causing the tinder to erupt in flames. “I was inside; there were several of us in there,” Willie Dishner, who was in the fourth grade at the time, told Reed, “and I looked and seen the walls coming down on top of us. That was the last I remember . . . when I crawled out, I came out from under the floor.”

In minutes, the storm left fifty-four injured and twelve children and the schoolteacher dead, ranging in age from six to twenty-four. News accounts describe scenes of a valley torn apart. Three homes and a flour mill were also destroyed, and several buildings damaged. Roofs were torn from barns and trees uprooted. Cars parked in front of the school were tossed over fifty yards.

Principal A. P. Noblin told the Bristol Herald Courier the day after the storm that he was inside the school when he saw the cyclone coming. “As it neared the school building it became a black cloud, it appearing as though a tremendous amount of dust had been gathered,” Noblin said. “I think I yelled. It struck the building. The next thing I remembered I was standing knee deep in a pond 75 feet from where the building stood before it was demolished.” Noblin suffered cuts and bruises, according to the account in Reed’s manuscript.

Parents of schoolchildren described the helplessness of watching the storm approach. “I was coming in with my truck, . . . and saw the tornado dip down into the valley,” Jim Morrison told the Johnson City Staff News in a story published the following day. “I saw it approach the school. I had three children in that school. My heart stood still as the tornado hit the school and tore the roof off, and the building collapsed. I hurried down to the school. After frantically searching under the boards, I found my son, Kyle, 9 years old. . . . I dragged him out. He has a fractured arm and leg.”

A. P. Carter’s experience echoed those of others in the community. He saw a cloud that he described—in his daughter Gladys Carter Miller’s words, captured in Reed’s project—as “right yellow-looking, and just a-rolling.” As rain began to fall, Carter climbed into his red Chevrolet sedan and drove over wet, ruddy roads in the direction of the school, where he probably saw smoke boiling above the treetops. By the time he arrived, Carter witnessed a dystopian scene: the bodies of the dead and injured were scattered over the field, the rain soaking those who were huddled over them. Volunteers carried buckets of water to put out the fire, tractors grumbling through the field to pull the school’s wreckage apart. Gladys recalled her father remembering “people screaming and crying and wringing their hands, picking up dead and crippled children.”

A. P. jumped into action to help those who were carrying bodies away from the fire and helping the injured into cars and onto flatbeds of trucks so they could be transported to a Southern Railway passenger train in Clinchport that would take them to Bristol. As he worked, Carter would have heard the screams of mothers and the cries of children. He would have heard so many engines, the whine of sirens, the frustrating spin of tires in mud, the shouts of those coordinating rescue traffic in and out of a place that might ordinarily see a car or two pass by in a day.

And when he had done what he could, when the last body was put into the ambulance and the fire extinguished, he would have climbed into his car for the long ride home, his clothes pasted against his skin, mud and blood covering his boots, his knees, the cuffs of his white shirt. It would be under his fingernails, the smell of smoke in his hair. He would be haunted by the twelve children and one teacher whose lives the storm had carried away.

That night, he’d pick up a pencil, sit down at the kitchen table, and try to put what he had seen into words, to puzzle those words into stanzas. A. P. was more of a song collector than a songwriter, but the words might help the sounds, the images, the smells find their way out of his head. The music might offer the grieving parents some comfort if that were even possible:

Oh listen today to the story I’ll tell

Of sadness and tear-dimmed eyes,

Of the dreadful cyclone that came this way

And blew our school house away.

Rye Cove (Rye Cove), Rye Cove (Rye Cove),

The place of my childhood and home,

Where in life’s early morn I once loved to roam

But now it’s so silent and lone.

When the cyclone appeared, it darkened the air,

And lightning flashed over the sky,

And the children all cried, “Don’t take us away,

But spare us to go back home.”

The song’s lyrics and the blend of the Carters’ voices haunt the listener, particularly in the knowledge that it was written based on A. P.’s own eyewitness account. But even more haunting is the dialogue attributed to children begging God (based on the last stanza, which references seeing them again in heaven) for their lives. In a devoutly religious central Appalachian community, in a chiefly Protestant region where the promise of life beyond death is carved into most gravestones, the children’s plea leaves me wondering if A. P. questioned how a divine being could have allowed a storm to wipe out so many young lives.

The song was released to mixed reviews in the community. Reed’s interviews suggest that, understandably, many in the area were so traumatized by the event that the song became a musical trigger too painful to hear or sing. But the Carter Family had fans far beyond the little community of Rye Cove who would buy up every new record they released. “Persons further removed from the scene and not personally affected,” Reed wrote, “. . . can enjoy singing about the tragedy.”

“The Cyclone of Rye Cove” continued to circulate several decades later and was even recorded by other artists. Part of Reed’s research was dedicated to determining if the song had been immortalized throughout the region. She collected eight “variants” of the song in Virginia, Tennessee, and North Carolina and analyzed the lyrics of each to make the case that the Carter Family’s version can be considered a ballad that passed into the oral tradition.

At the nearby Natural Tunnel State Park, visitors can go on a hayride through the Cove, listening to park interpreters talk about the area’s ecosystem and history. Occasionally, they’ll stop at the edge of a field to talk about the cyclone and its tragic end. Most of the time, no one on the hayrides has ever heard of the cyclone of Rye Cove or the song (or even the Carter Family). But interpreter William Cawood remembers an older woman who sat quietly through his story until the end. Finally, she spoke up. “I was eight years old and in the second grade,” she said, “when the tornado struck my school.” She also talked about how she lost friends that day.

Cawood met another survivor, a ninety-year-old man participating in a baptism as Cawood was navigating the Clinch River by canoe. He told Cawood about his family’s two corncribs, which sat a “wagon bed’s width apart.” The cyclone took one of them, he said, and left the other.

Today, an elementary school occupies the site where the Rye Cove School once stood. The fields around the school are dotted with sparsely spaced houses and grazing cattle but look much the same as they would have when farmers pushed their hats back to marvel at the yellowing sky and boiling clouds on that day in 1929.

I took my children there one Sunday afternoon a couple of years ago. They were not surprised to hear of a mountain tornado, since they’ve heard the story about a small tornado that damaged our own home in 2010, one month before our first child was born. But they were troubled by the deaths of children their own age who, like them, went to school that spring morning with no thought of never coming home.

The original school bell is mounted in a brick memorial there, the names of those who perished listed on a plaque. My ten-year-old daughter touched fingertips calloused by banjo strings to the names. A couple of the children shared the same surname, and likely some kinship, as the musicians who immortalized them in song: James Carter, Polly Carter . . . the list goes on. My own kids were too young to fully understand the grief in A. P.’s words; still, they sensed sadness in the way he, Maybelle, and Sara Carter retell the memory of mothers and fathers “searching and crying” for children just like them, only to find them “dying on a pillow of stone.”