한년 (WOAMN, WHITE)

On Korean Drama and the New Southern Gothic

By S. J. Kim

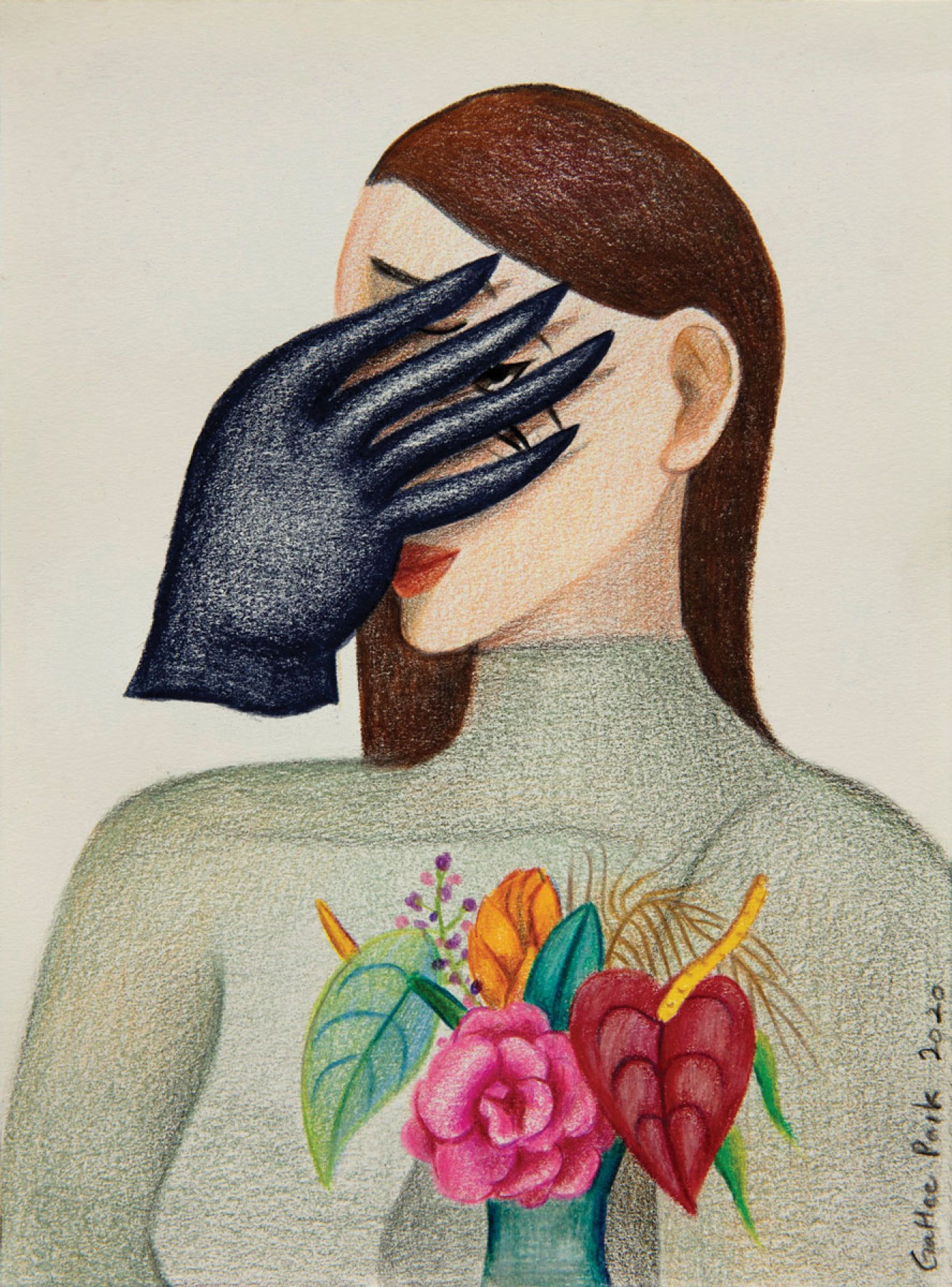

A Woman with Black Glove, 2020, color pencil on paper, by GaHee Park. Courtesy the artist and Perrotin. Photograph: Guillaume Ziccarelli

DRAMATIS PERSONAE

THE STUDENT, a PhD candidate studying abroad

THE INSTRUCTOR, a junior academic on probation

YOU, a character in a Korean drama

NEON VERNACULAR, a seminal text by poet Yusef Komunyakaa published in 1993

TWENTY CONTESTANTS OF THE 2013 MISS KOREA PAGEANT, a spectral chorus

I. 곡성

[AN OPEN FIRE]

Manchester, UK. A studio flat in Chinatown. THE STUDENT is in bed holding a well-worn copy of NEON VERNACULAR to her chest. There’s a pen between her teeth. Beside her is a yellow legal pad, flipped to a page filled messily with half-thoughts, mostly fragments from Komunyakaa’s work.

The student thinks often of a dead white woman she knows and how her killers were two Black men. When the student thinks about Eve’s death, she thinks more about the two Black men and how they got caught because they told people about Eve asking them to pray with her before they killed her. The student didn’t know Eve when she was alive, but after her murder, the student was out late one night, walking across an unusually quiet and empty campus when she found a rain-soaked photograph of her on the ground outside of the student union building. The student imagines someone who had feelings for Eve meant to say a private goodbye to her. Only someone who had a lot of feelings for her wouldn’t have thought through leaving her out in the rain like that, to get stepped on, her face gone damp and distorted like that.

The student, she would have burned her photograph in an open fire, smoke rising to the sky, along with something they

both loved, for her to take with her to that other place.

II. 여교수

[LANGUAGE OF FLOWERS]

London, UK. An academic office in Bloomsbury. THE INSTRUCTOR is holding out a box of tissues with both hands to a figure seated on her sofa. She is trying to maintain a neutral expression.

In the classroom, the instructor finds herself saying things like, “This scene makes me wonder if this was the first big death she experienced in her life.”

When the instructor thinks of death, she often thinks of white women. Yusef Komunyakaa writes, “Stopped in this garden, / Drawn to some Lotus-eater.”

The subtitles say:

[A Black man is singing, “I’m here, as if I never left,” a work song.]

The instructor thinks of the white woman she upset in her second year of teaching, trying to teach someone else’s syllabus as if it were her own. She was leading a seminar on Pride and Prejudice. She asked the students to consider that the last few lines of the novel saw Lizzy compared to “pollution.” “I disagree,” the white woman said. “This is a love story. This is the most famous love story in the world.” The white woman was respectful, polite, firm in her conviction, yet tremulous. The instructor wanted to ask her what exactly the white woman was disagreeing with, but she feared the white woman would cry.

It was the same year the instructor felt she had to tell her students: it’s okay to say Black. She was leading a seminar on Heart of Darkness. The instructor said, “It’s okay to say someone is Black.” That was when the instructor learned to hold the silence.

The instructor learned to be more careful, evermore, fixing her gaze to a white woman’s watery blue eyes. The instructor writes her own syllabuses now, sometimes, but she holds on to a ghost: pale polite hair, pale polite face. The visitations grow more unsettling each time. She swears, all those years ago, she was wearing white.

III. 여학생

[SHE PUTS SOMETHING ON]

Manchester, UK. A studio flat in Chinatown. THE STUDENT is still in bed but with an open laptop now, staring at Yusef Komunyakaa’s Wikipedia page and wondering what the actual hell she is doing with her life.

There is a book the student loves deeply. She has read it many times. She longs to inhabit the text as her own. But, it’s complicated.

When she tries to write about it, she fears she is not herself—or something worse. When she tries to write about this fear, the student feels further distracted. But the fear, she thinks, must be a part of it, too, her deep love for a book that is and is not hers. Must she claim it out loud? If so, how? What are the words she must say? What are the words?

The student doesn’t want to read or write anymore. She opens a new tab. She puts something on. A woman in white stands at the river’s edge. She clicks the subtitles off, then on again.

IV. 우리

[VOICES OF LITTLE GIRLS]

Seoul, Korea. A grand hotel lobby and, later, a 포장마차. YOU move about fretfully, frenetically.

You are a tertiary female character in a Korean drama. You are small and all your clothes are oversized. You wear a lot of pastel. Your hair is always in slight disarray and your wide-lens glasses distract from your face. You are in your thirties but you have the voice of a child—rather, how we are taught to imagine the voices of little girls.

You are wed, briefly, to a humorless man. At the tail end of the reception, you discover your ceremonial husband kissing another woman with a kind of passion always denied to you. You flee from the sight and he chases you through the hotel lobby to inform you, loudly, in that grand, resonant space, that he never loved you. He says he was only following the advice of his mother to marry a simple, somewhat stupid girl who would serve him well.

Time passes with the central arc of the drama. Now, you are confessing to the secondary male lead that you wanted to kill yourself that night of your wedding. You fixed your gaze to the 한. You took your shoes off.

Your voice is raised and tremulous. You have no idea how girlish you sound. You have no idea that when you speak, the music that plays is a jaunty, tinkling piano tune, a parody of ragtime without any sadness in the soul, or perhaps without any soul at all.

This is the nature of your sincerity. You do not know that this scene is not about you or your desire to die. This scene is about the secondary male lead realizing he is attracted to you.

V. 한놈

[HOW THE WORLD WORKS]

A continuum. TWENTY CONTESTANTS OF THE 2013 MISS KOREA PAGEANT stand in a circle and scream into the center endlessly.

In 2014, a white male professor from Princeton declared, “After the near-collapse of the world’s financial system has shown that we economists really do not know how the world works, I am much too embarrassed to teach economics anymore, which I have done for many years. I will teach Modern Korean Drama instead.”

In a mock proposal for such a class, the white male professor writes, “Although I have never been to Korea, I have watched Korean drama on a daily basis for over six years now. Therefore I can justly consider myself an expert in that subject.”

배수아 writes in <뱀과 물> (2017):

전혀 피곤하지 않았지만 이상하게도 나는 어느새 잠이 들었다. 그리고 내가 잠이 들자마자, 여자 심리학자가 와서 나를 흔들어 깨웠으므로 나는 아무런 꿈도꾸지못한채다시눈을떴다.창 밖은 여전히 어두웠다. 여자 심리학자 는방을나가기전과똑같이두건이달 린 검은 외투 차림이었다.

“지금 떠나야 해.” 여자 심리학자가 서둘렀다.

“지금 널 태우고 갈 트럭이 밖에서 기다리고 있어.”

“이제 꿈이 시작되는 건가요?” “바보 같은 소리 하지 마라.”

The white male professor’s proposal went viral in the wake of a series of official headshots for the twenty contestants of the 2013 Miss Daegu pageant making similar rounds, inviting derision of the women for looking all the same due to the grotesquery of plastic surgery.

In addition to the pictures being widely mislabeled as twenty finalists of the 2013 Miss Korea pageant, articles purporting to reveal a more true-to-life group photo of the women from Daegu used an image of twenty contestants from the 2013 Miss Seoul pageant instead. These errors remain largely uncorrected or glossed over, even in follow-ups with more images of the twenty women from Daegu who were further tasked with posing in what is described as their more natural states, more real, more human—these women, twenty in all, still holding their smiles, still holding their assigned numbers to be identified.

The white male professor writes, “The overall impression conveyed by a good modern Korean drama is of a land of truly handsome men and exceptionally beautiful, fashionable women. Korean women remain quite beautiful even after plastic surgeons have retrofitted their original, even more beautiful original Asian faces with pointed and straight Western noses and Western eyelids.”

The subtitles say:

[Is the dream starting now?

Don’t be stupid.]

VI. 우리

[ONE OF YOU MUST CHANGE]

Seoul, Korea. By the 한강 and, later, a 포장마차. YOU move about fretfully, frenetically.

In this scene, you are arguing with a woman who looks like you. She is possibly one of a number of your sisters, or she is your mother, or she is your aunt, or she is one of your sisters’ mothers-in-law, or she is your frenemy who deleted your presentation slides, stealing your one chance at a promotion, or she is your husband’s mistress. You are both standing ankle-deep by the bank of the . Your hair is long and dark. Your dress is long and white. One of you must change.

Your fight bears no consequence on the central arc. The piano music when you speak, even when you are shouting, is louder

than you.

You remind the woman who looks like you that you are a kind of doctor.

The woman who looks like you shouts for you to take the bones out of your words.

The subtitles say:

[Don’t be sarcastic!]

You fix your gaze to the once soft spot between the eyes of the woman who looks like you and you think of that time you started saying something angry to a white man for comparing you to his Asian girlfriend, and a white woman interrupted you to tell you, “Be nice!”

You change. You blow out your hair. You put on new shoes and seek solace in drinks with the secondary male lead. He has neither been married nor divorced and is a dental surgeon of some international renown. You drink and stare longingly into each other’s original, even more beautiful original Asian faces with your Asian eyes and Asian noses. The more you drink, the more bones grow inside your words.

VII.

ON KOREAN LOVE

[THE GRAVE DANGER]

Manchester, UK. A studio flat in Chinatown. THE STUDENT sits up in bed, startled, wondering where the screaming is coming from.

On Korean love, the white male professor writes of controlling and prejudiced Korean mothers determined to separate the star-crossed. He notes, “[As] a last desperate resort, there is always the announcement that one or the other of the two young lovers will be sent to study in America, which seems to be the dumping ground for the young Koreans who have fallen in love without their mother’s permission. Rarely do the mothers realize the grave danger to which they thus expose their offspring—the possibility that in America the offspring might fall in love with and marry someone other than a Korean.”

He pairs this with an image of an Asian man with a white woman, followed by an image of a white man with an Asian woman. These are not stills from a drama. This is the white male professor’s balanced, real-world texture. The student accepts it is her inability to estimate the ages of white people that makes the white man look so much older than the Asian woman next to him. The student quells the instant hate for his lobster red face and low open collar, that stupid heavy chain around his thick neck. The student relents the Asian man and Asian woman are Korean, according to their original, even more beautiful original Asian faces with their Asian eyes and Asian noses. The student relents the white man and white woman are American.

VIII. 여학생

[SOMETHING MORE SENSELESS]

Manchester, UK. A studio flat in Chinatown. THE STUDENT holds NEON VERNACULAR close as she pulls the covers over her head and closes her eyes, wondering if anyone else can hear it, all that screaming.

The opening line of Wilkie Collins’s The Woman in White states, “This is the story of what a Woman’s patience can endure, and what a Man’s resolution can achieve.” The student notes that the woman in white is a personification of the fascination with how bodies relate to society. The student notes that the woman in white flits in and out of the narrative, embodies a death-in-life ambiguity, and renders the world oddly spectral.

Edgar Allan Poe writes, “The death [...] of a beautiful woman is unquestionably the most poetical topic in the world, and equally is it beyond doubt that the lips best suited for such topic are those of a bereaved lover,” and the student notes this, too, and wonders if the fucking small-mouthed, lily-handed creep must reach in and grab white women in a particular way that the student cannot fully understand.

The student is compelled to study the shadow of the woman in white and finds it to be an impression. Yusef Komunyakaa writes, “As if gods wrestled here.”

In “Work,” the man of resolution is a hired Black man working the garden of his mistress who wears her whiteness like a trap. Instead of unexpected visitations, the white woman lies deathly still in the full light of day, in the garden of an antebellum house that:

Looms behind oak & pine

Like a secret, as quail

Flash through branches.

This is the Deep South evoking the hunt of Old World Europe. This is Oxford, Mississippi. Through Komunyakaa’s working, the landscape so steeped in tragic traditions is also a jungle of the Eastern world at once:

Leaning into the lawnmower’s

Roar through pine needles

& crabgrass. Tiger-colored

Bumblebees nudge pale blossoms

Till they sway like silent bells

Calling. But I won’t look.

Exoticism is the word the student spits and chases with salt, suggestive of an otherworldly warring, but at heart the student resists overt connections to the Vietnam War, as tempting as it is with Komunyakaa’s service as a war correspondent that earned him a Bronze Star. The student knows that the image of tigers in jungles is more storybook than history. More so than the nightmare of the Vietnam War seeping into the suburban scene, hellish suburbia invades the Black imagination, mutating familiar terrains into the lush rot of a Southern gothic, distorting the histories of wars, wars, wars into something more senseless than before. The student knows. Or, at least, she suspects.

IX. 한놈

[A FASCINATING HISTORY]

A continuum. TWENTY CONTESTANTS OF THE 2013 MISS KOREA PAGEANT are still here, still standing in a circle and still screaming into the center—endlessly. This is what endlessly means.

The white male professor clarifies that most of the Korean dramas he watches are historical. “I find it to be a fascinating history that should be known more widely in the world,” he says. He praises the ability of Korean actors, particularly the ability to cry on command.

He notes, however:

Often the endings of a drama series are let-downs. They seem hastily contrived and are often a bit corny (as we would put it). I think even I, an economist, could do better.

Furthermore, forgiveness of even the most egregious behavior seems to be a theme in Korean dramas. Sometimes one wishes that the really bad characters would be punished more. Is forgiveness of this sort really a reality in Korea?

X. 여학생

[WHITENESS FORETOLD]

Manchester, UK. A studio flat in Chinatown. THE STUDENT runs the pad of her thumb along the edges of NEON VERNACULAR, knowing by feel which folded indent marks what poem.

The impression is a shallow bed-grave with space only for immediacy and baseness. The woman in white is reduced to this glaring image:

I won’t look at her. Nude

On a hammock among elephant ears

& ferns, a pitcher of lemonade

Sweating like our skin.

“Nude” is the only word directly describing the white woman in the entire poem. This degradation unites her with the Black man through “our skin.” Though the Black man resolves again and again throughout the poem: “I won’t look at her,” the blinding color of her is all he sees and understands of the white woman directly.

The rest of her is imagined through details of the domestic world around her. Even the details of her body beyond the whiteness of her skin must be further imagined through the landscape. Her eyes blue as “Afternoon burns on the pool / Till everything’s blue.” Her hair golden as the summer heat, as fine as the pale daffodils. Even the idea of summer must be inferred from the lushness of the jungle garden around her, from the “Scent of honeysuckle.” She sits like a glowing fruit amidst the elephant ears and ferns. The curves of her figure are detailed only through the fat pitcher of lemonade, the taste of her imagined sweetly, quenching a thirst, yet shudderingly sour, shockingly chilling amidst the Mississippi summer heat, as is the foreboding luminosity of her whiteness foretold by the pale blossoms that toll of death.

Kate Daniels writes, “When Komunyakaa’s gaze settles on white women, I find myself represented in ways I can’t tolerate.”

Natasha D. Trethewey writes, “Perhaps Daniels was too busy seeing herself [...] as opposed to losing herself in the world of the poem to give it the close reading it deserves.”

Speaking only through the color of her skin, the white woman is a stagnant and largely imagined thing, a still life framed by the domestic world around her. As poetic as Poe could ever hope for, she is so much an object of art that she may as well be dead. She is fixed here, unlike her nameless husband who is offstage, unlike the idyllic gesture of “daughter & son” neatly marking her nameless children as archetypal as the flashy cars they drive off in, unlike even Roberta the cook who is off for the day:

Her husband’s outside Oxford,

Mississippi, bidding on miles

Of timber. I wonder if he’s buying

Faulkner’s ghost, if he might run

Into Colonel Sartoris

Along some dusty road.

Their teenage daughter & son sped off

An hour ago in a red Corvette

For the tennis courts,

& the cook, Roberta,

Only works a half day

Saturdays.

Roberta’s absence serves as a marker of time, albeit in strange increments of “a half day,” as the only reliable evidence that time is, indeed, passing. Roberta is also the only person of the household—but not family—named in the poem. Her role and her naming have no more significance than that of the flora and fauna around the white woman, itemized along with the trappings of wealth, alongside the plants, flowers, and creatures surrounding the mistress of the house as props, or more suggestively, as ingredients laid out for a working.

The student reads the poem as a spell.

Black magic lurks in the shadow of the antebellum house.

Black magic lurks in the shadow of the antebellum house.

Black magic lurks in the shadow of the antebellum house.

The cursed aristocratic family on their cursed land are decaying time immemorial, “Along some dusty road,” it doesn’t really matter where exactly, as long as it’s a place like Oxford, Mississippi.

Here, Faulkner’s ghost holds no more power than the fictional Confederate Colonel Sartoris who, in turn, holds no more power than Roberta the cook. Their ineffectual trinity offers no resurrection for the woman wearing her whiteness. The only named entity with semblance of agency, of all the entities haunting Southern soil that could have been invoked, is Johnny Mathis on the radio. The unexpected apparition of the jazzy pop singer serves as a bizarrely fitting oracle, his whisper signalling the turning point of the poem:

Afternoon burns on the pool

Till everything’s blue,

Till I hear Johnny Mathis

Beside her like a whisper.

I work all the quick hooks

Of light, the same unbroken

Rhythm my father taught me

Years ago: Always give

A man a good day’s labor.

I won’t look. The engine

Pulls me like a dare.

The student finds comfort in the black humor of the bard of jazzy pop cast as some sort of spirit medium invoking the parable-like words of the speaker’s father, crooning impending doom. The student is moved by irreverence. The strangeness of this casting is in the vein of the beastliness of bumblebees in the jungle garden, the way a sweaty pitcher of lemonade speaks of sex, gender, and race heavy-handedly, as the student does, as the student longs to, but also of how “our skin” must be cool to the touch, corpselike, in spite of and especially because of the contrast to the Southern summer heat, the cool glass reflecting the ambiguity of death-in-life.

The student listens to the jazzy pop of a closeted, then outed, gay Black man and reflects on language as our public and private selves.

XI.여학생

[DIALS A NUMBER]

Manchester, UK. A studio flat in Chinatown. THE STUDENT opens her eyes. She throws off the covers but keeps NEON VERNACULAR close. She takes a deep breath, all the air her lungs can hold. She screams back.

The student is in the final year of writing up her doctoral thesis when her family nearly goes bankrupt. The student desperately needs to go home to be with her parents who can’t speak English very well. She is sitting in her supervisor’s office trying to find the right words for the situation. She wants to protect her parents. She wants to protect herself. The student has learned to be careful in how she presents herself. She is careful, asking about the possibility of time off and who she ought to consult regarding possible complications with her visa.

“Why aren’t you crying?” her supervisor asks her. “You should be crying, talking about these things.”

The student does not know what to say.

“You are depressed,” her supervisor says.

The student tries to explain everything again, that what she needs from the meeting today is—as the student is speaking, the supervisor picks up the phone on his desk and dials a number. The student does not understand but the supervisor is already speaking to whoever is on the end of the line, saying, “Yes, I need to report a student who is depressed.”

The student longs for a body of water. She longs for a body.

XII.한놈

[FERTILE AND BREATHTAKINGLY BEAUTIFUL]

A continuum. TWENTY CONTESTANTS OF THE 2013 MISS KOREA PAGEANT are screaming even louder now.

Of a family losing all of its savings and its house, the white male professor writes, “It will cause much ‘stress.’ Finance gone awry always is a major stress-begetter in Korean drama, which is why it always is part of a good drama.” There is no explanation for why stress is in quotes.

Instead, the white male professor explains that Koreans react to “stress” in mysterious ways such as seeking medical attention, drinking, and going outdoors with a particular penchant for standing next to and staring at “some river bank or ocean beach.”

The white male professor notes, “Koreans inhabit a land that is both fertile and breathtakingly beautiful. Yet, endowed with all of these blessings, the Koreans in these dramas seem to spend all day and night making one another miserable and sending to God several million sighed ‘Aigoohs’ every day. What a pity!”

In an interview for the Korea Times, the white male professor says his proposal for Modern Korean Drama was “impromptu,” meant to “entertain” a conference of “health insurance” experts from Korea and Taiwan.

“Actually I do not teach such a course, but economics instead,” he says.

XIII. 우리

[WHAT YOUR FATHER TAUGHT YOU]

Seoul, Korea. A modest home in the suburbs, but later YOU will end up at a again. YOU are screaming now, too. YOU have always been screaming.

A pair of gangsters in black suits turns up at your house, armed with steel pipes. They work for the merciless loan shark your father is indebted to. You are the one stupid enough to answer the door. One of the gangsters takes off his jacket and rolls up his sleeves to better swing his pipe around and to show off his tattoos, tigers and dragons that look more like blue-veined snakes. He doesn’t hit anything, yet, but it’s not hard to imagine the sound of a bone cracking; you can call it forth just as you would the imagined voice of a little girl. The gangsters want to know if your father is home, but you are home alone; it’s just you and a number of women who look like you. The women are hiding behind the curtains, in the wardrobes, beneath the bed. Some are under the floorboards, mouths wide, hoping for something nourishing to seep through the gaps. There are women in the drains, too, but you cannot bear to think of them right now.

You ask the gangsters if they have mothers, sisters, wives, girlfriends, daughters, any women and/or children in their lives who matter to them. This is what your father taught you to ask them. You beg them to not kill you or the nineteen other women who look like you until you can all be mothers to shining sons. This is how your father taught you to beg. You sob as you vow that your sons will be better than your father who is not home. Your father who is not home has never been home, not once, but your sons, they will be, each son a two, no, three-story home, each son a home, each son a mansion. This is what your father taught you to vow. Your bony words are choking you. You sob until the gangsters leave. Instead of piano music is the sound of the men sucking their teeth.

XIV. 여학생

[BRIGHT JEWEL TONES]

Manchester, UK. A studio flat in Chinatown. THE STUDENT understands she has always been screaming, too. She feels herself untethering from the fabric of space-time. She feels as if NEON VERNACULAR may be screaming with her, but what NEON VERNACULAR is trying to tell her is that we are traveling from time to eternity.

If narcissus tolls of death, cinnabar insinuates how violent the deaths will be. The clarion call of an unnamed Johnny Mathis song with its “quick hooks” and “unbroken rhythm” gives way to the “Scent of honeysuckle” that bleeds into:

Sings black sap through mystery,

Taboo, law, creed, what kills

A fire that is its own heart

Burning open the mouth.

The culmination of “Work” is not the act of transgression between the white woman and Black man but what follows—the “Gasoline & oil” that takes us to the end.

The husband off stage who is bidding “on miles / Of timber” is part of the aftermath. The husband is an audacious man who swears oaths, and wears his whiteness as a badge, as a mask. He drives nails into miles of timber, he stakes it all into the red earth, and he sets everything ablaze.

The student thinks about the many field trips she took to the Levine Museum of the New South, the many relics they have on display there, the pristine masks, the shining robes, not all white at all, but bright jewel tones for the highest ordained. Where did they come from, these robes, these masks? How and why were they so perfectly

preserved? Whose hands continue to care for them?

The Black man cannot account for the aftermath of the transgression of two mere bodies. As “Work” closes, he “can’t say why,” voiceless altogether.

XV. 여교수

[HANG THEIR HEADS]

London, UK. An attic flat in the suburbs. THE INSTRUCTOR unclenches her jaw.

The instructor is lying in her bed, clutching her phone. She is waiting for a call. It is 3 a.m. She thinks of the editor from that magazine who wrote back within hours to say that he had no time to read her essay, and besides, he wasn’t sure if their website could support Korean characters. The instructor thinks about her first time meeting an editor from a major publishing house, who came to visit a writing class during her master’s. When asked what the editor was looking for, the editor’s response was that it was easier to say what she was not looking for. For example, she was currently editing a book by a Korean American woman, so, she wasn’t looking for any more Korean books for the next year or so. The instructor thinks about the roomful of eyes turning on her, all eyes except the editor’s. The instructor thinks about how careful the editor was to not see her for the whole of the hour.

Had she a book, she is unsure what is the name, what is the name she would put to it. What she remembers best about Korea is the recurring dream of a pale snake outside her bedroom window, calling her name. The name she thought could be cut away from her like tonsils, a kidney, a spleen. She knew not to answer it then, but if she heard that low, soft beckoning now, she fears she would surrender. She fears she would say yes, I will reside in the thin fleshy walls of you, slick with your venom; it is what I have always wanted, nothing more than to succumb to slow decay amidst all the soft, blooded things, and, too, all the fine, sharp parts inside a snake.

The instructor whispers into the glassy dark surface of her phone: Narcissus is the namesake of Echo’s doomed love for a beautiful and stupid boy. It is the flower that lured young and sweet Proserpine to the dark embrace of Pluto. The Narcissus tazetta is sometimes cited as the Rose of Sharon, the flower symbolic of Christ from the Song of Solomon. Victorian folklore dictates that daffodils do not belong in the domestic space for the way they hang their heads, bringing tears and unhappiness, and are as pale as death. The narcissus is relegated as a grave flower befitting only the decoration of a final resting place. The Lotos-Eater speaks in a language of flowers. Lush rot, lush rot, it was not you who put these words together. You need to cite your sources. You need to read Tennyson.

XVI. 여학생

[RAISES HER HAND]

Manchester, UK. Or maybe London. A studio flat in Chinatown. Or maybe a classroom in Bloomsbury. THE STUDENT’s phone alarm goes off. She can barely hear it over the screaming, but it’s time to call her mom.

The student raises her hand and says, “It’s Roberta I’m worried about.”

XVII. WOAMN

[WHERE THE SICK LIE]

London, UK. A classroom in Bloomsbury. THE INSTRUCTOR’s phone alarm goes off. THE STUDENT is lost in a continuum.

THE INSTRUCTOR apologizes and turns off her phone.

In 1997, bell hooks wrote in “Representing Whiteness in the Black Imagination,” “If the mask of whiteness, the pretense, represents it as always benign, benevolent, then what this representation obscures is the representation of danger, the sense of threat.”

In 1977, Yusef Komunyakaa published the first issue of a non-profit literary magazine founded in Fort Collins, Colorado. The first issue of Gumbo contains a poem by Gloria Watkins called “Where the Sick Lie”:

death is

always asleep

in the middle

room

feather mattress

feather pillows

bed that rocks

like a boat

I fear the

water

black folk

can’t swim

in the room

she lie

blood in the

wash pan

empty this

dream

a bed of water

fat old woamn

chewing tobacco

Death in

the spitoon

The student raises her hand and says, “Was woamn intentional?”

The instructor says, “We are animal. This is a poem.”

XVIII. 우리

[GREEN AND GOLD AND MUD]

Seoul, Korea. YOU just want to go home, but YOU don’t want to be the one to say so. Home is—where, exactly? 우리 한강갈까 포장마차 갈까? 아이씨 모르겠다, 곡이나 부르자. 아, 아, 아맞다, 엄마한테 전화해야지.

In this scene, you are at a conference attended entirely by women who look like you, women who are you, but, of course, your frenemy has deleted your presentation slides. You must speak “impromptu” and “entertain.” You were never going to get a promotion, anyway.

This is what you say:

Our home has many occupants: mother, father, black cat, black snake, and me. Black dog is buried in the garden, beneath stones we brought down from the mountains (but not the mountains mother grew up in).

Mother’s work is in the fields, ankle-deep in wet dark earth shot through with green. Father’s role is to reap what she sows.

Father says, “Do your job well.”

Mother says, “Terrible things will happen if you don’t.”

It is up to me to keep black cat and black snake from eating one another. Black cat is soft and sleeps, small ball in my lap. I am cruel to black snake. Ugly black snake, long as I am tall.

One day, black snake runs away.

I run into the fields and I call out for black snake. “뱀!” I call, “뱀!” I slap my thigh with the flat of my hand as I would when I call for black cat, but this method only ever worked with black dog. Still, I stand in the center of the green and gold and mud and call out for black snake. “뱀! 뱀! 뱀!” I must bring her home.

But when I call, I see that the ground is made up entirely of snakes. They are packed tight and writhing all together toward the horizon. One is as wide as my body is long, patterned in copper and verdigris. I

follow the slow pulse of her body as far as my eye can see, but cannot see her tail beyond the horizon.

This is what the subtitles say:

[A woman in white rises from the water, wailing. Snakes are pouring out of her mouth. This is a traditional Korean story, and she is looking for an ending.]

XIX. 한년

[WE JUST CALL THEM DRAMAS]

A continuum. TWENTY CONTESTANTS OF THE 2013 MISS KOREA PAGEANT standing in a circle are joined by YOU who can’t find the way home and THE STUDENT holding NEON VERNACULAR close, endlessly. All of the women are still screaming.

THE INSTRUCTOR materializes in the center of the circle and begins to weave through the crowd without really noticing where she is or where she is going. She has her phone pressed hard to one ear. In the other is her finger, poised like the barrel of a gun.

엄마! 엄마나야. 엄마잘들려? 아,아니야, 안 바빠. 밥? 밥 먹었지. 먹었다니까.

This is the ending we have been searching for. We collate six photographs and add our own to round out the circle of seven: our sister, our mother, our aunt, our sister’s mother-in-law, our frenemy who deleted our presentation slides, and our husband’s mistress, and we who have been searching. We will disseminate this image. We, too, will circulate. If we’re lucky, we’ll go viral. We will no longer be told that what is unspeakable is unintelligible. And we will have words to say about our diminutive and interchangeable selves.

The subtitles will say:

[Please could you kindly rethink your takes on Asian women?]

This is the ending we have been waiting for, six dead women who look like us. Be grateful it is not more. Our mom becomes sick. We tell ourselves that her fever is from the vaccine, but we know she is seeing the self she could have been in the photo of the mother with her smiling sons. We know she is seeing us in a daughter left behind. We tell her it’s not her. We tell her it’s not us. We tell ourselves these things, too. They are not us, these women. But everything is difficult to remember. We want to keep her on the line, our mother. We ask her what she’s watching. We ask her about any good dramas. Between us, we just call them dramas.

We learned to love them from her. But lately, our mother says—nothing, I don’t watch dramas anymore. They make me too angry. They make me too sad. We are silent for a long while, us and our mother. We want to keep her on the line. We ask her about the mountains she grew up in, but it is we who start telling the story of a man who gets lost in the mountains. Deep into the night, he roams desperately through the dense woods until he comes across a woman in white who offers him a cool drink of water from a stone cup. He does not hesitate to accept. She is beautiful and he is thirsty. When he drinks, it is the most refreshing, satisfying thing he has ever tasted. He drinks and drinks from her stone cup. He drinks until the sun rises. In the full daylight, his vision shifts, and the woman in white is gone, but he is still holding her stone cup. The cup is full of blood. He can taste the thickness now. He can taste the salt and metallic tang. It’s coating his teeth, his tongue, his throat. His belly is full of blood. He can feel it sloshing. More still is dripping into the dark stone cup. The man looks up into the branches and above hangs a freshly skinned snake, its tail in a knot. Milk-eyed and open-mouthed, it drips, and drips. Our mother is still there, on the end of the line. Time passes with the central arc of the drama. We are still here, writing our own syllabuses sometimes. 아이구, 이 한심한년아 —