I Love the Way it Sounds

By Lynell George

Synthesis BB, 1983, by Ida Kohlmeyer © The Estate of Ida Kohlmeyer. Courtesy the New Orleans Museum of Art: Gift of Arthur Roger

Some children sail off to bedtime dreams with “Once upon a time...,” others by way of “In an ancient land...” Each is an invitation, a story spinner’s device to travel to some exotic elsewhere—gentle lullabies in their own right. Yet, as far back as I can remember, I knew no better incantation to invoke an antique place as: “Let me go get down that pot...”

Said “pot” was sunshine-yellow, enameled cast iron, fitted with a heavy matching lid. As well, said pot, more a deep skillet with detachable wooden handle, was only used twice a year to prepare specific centerpiece meals. I knew it simply as “The Gumbo Pot.”

No family recipe exists on paper. Not a one. Sometimes when I reveal this, I know that people assume I’m being coy. But my mother didn’t write them down. Neither did her mother, my grandmother, nor did my grandmother’s sister, my great-aunt, who was a sorceress before the burners. I learned as they had—by repetition. Trial and error. “Guesstimates” and internal arithmetic. Sense memory nudged you forward. These women simply “got down that pot” in their respective sunny Los Angeles kitchens and, after some murmuring and some laughter—and the busy rhythm of knives chopping onions, bell pepper, and celery—someone, usually my mother, began unspooling lyrics of faded, gauzy songs sung in a language that was both familiar and enticingly indecipherable.

Gardez, M’sieu Banjo, Misi Banjo

Comme il est bien, taillè

—Traditional

It all rose up; entwined: The scent of flour and fat toasting into a roux; the sound of my mother’s waltzing, rounded notes, drifting in and out of Creole patois, that would only a few times a year transport us elsewhere. Someplace I hadn’t been, but I would come to know, to love: New Orleans.

Years after my grandmother and great-aunt had passed away, I realized that when my mother cooked in this particular pot, the walls and floor would disappear and we were somewhere else, neither present nor past, but together: In her humid New Orleans bedroom with Lee Dorsey or Paul Gayten and his band on the record player; on the front porch in earshot of the front room radio, listening to Dave Bartholomew and Antoine “Fats” Domino charge through. My mother’s voice would bounce with the up-and-down propulsion of those tunes, some of them stitched with lyrics that were, as she explained, innuendo, but I heard as “in your window.” I imagined the sly phrases and glinting, syncopated notes floating through the white eyelet curtains of their narrow wood-frame house in the Seventh Ward. I needed to absorb this. Be conversant.

Well lawdy, lawdy, lawdy Miss Clawdy

Girl you sure look good to me

Well please don’t excite me baby

I know it can’t be me

—Lloyd Price

In these rituals, my household wasn’t unique. In time, I noted a theme, a puzzling truism. Many of my elder relatives and their friends—and friends of friends—had moved heaven and earth to get here—to Los Angeles—yet spent so much time attempting to replicate some sense of where they’d left. The place they always referred to as Home, even if they had lived in Southern California for decades. Home resided in that middle-distance stare. They carried their stories close like a sweetheart’s picture in a locket. Many of Mother’s friends had uprooted themselves from their own very specific Souths (rural, city, deep)—locations that left signatures on their spirit. I could hear their histories in the cadences of their speech, the music of their dialect and drawls; even in the varied way they sucked their teeth or rolled their eyes.

Their Texases, Mississippis, Alabamas, and Tennessees were on full display at backyard or city park gatherings across the L.A. basin—the picnics and fish frys, cookouts and barbecues where folks trotted out their birth-home’s signature mains or sides, from deviled eggs and monkey bread to Sock-it-To-Me Cake and lavish stone fruit cobblers, studded with aromatic peaches and apricots plucked from backyard trees. All this: An homage to the past and gratitude for the “paradise” they’d come all this way for; the L.A. they’d sunk their teeth into.

That snap of a floral-print tablecloth, shaken loose and then smoothed into place on a picnic table, announced that the serious business of the day was to commence. Women and men took their ritual places at the smoker, or behind the well-worn oilcan grill. The adults, moving with easy purpose, juggled utensils and set up ancillary tables, their strides broken only to bend to deliver admonishments in blade-sharp, between-teeth whispers to us restless children: Either help or get up from under my feet! So help me!

Simmering in the backdrop, its own essential presence: the portable, tube-amplified turntable. Stacked on its spindle was a smorgasbord of 45s alternating with LPs, all of which were selected as carefully as the representative side dishes. These records, brought by guests, also claimed far-flung points of origin. The South emerged vividly this way too: in this group, Mississippi and Texas and Louisiana most frequently. Within these exchanges of sustenance, what became clear was that no one was trying to push past the South; no one had escaped it entirely. No one left everything behind. Not really. Try as you may.

Maybe that story tailing you felt heavy or sad or regrettably incomplete. Maybe circumstances flipped the coin—“stay or go”—for you. Or now, with the difficult choice behind you, maybe you preferred instead to remember only the kinfolk and kinship. Reconvening with others who had made similar journeys, with those who understood the tough arithmetic of compromise, they found this was where joy bloomed: in the ritual of connecting and sharing the keepsakes of a very particular Black American South that had traveled so many miles in memories. It was another way of saying grace.

After a while, the music circling round and round on the turntable cast its spell. Sometimes voices quieted and that music took center stage. The ballads and blues and the joy spark of jump swing lifted the latch to memories of old dance halls, high school dances, porch parties, discreet after-hours basement meetups. These tunes—across genres, across generations—were layered, sometimes complicated landscapes in and of themselves.

But at these parties my mother’s music wasn’t on the spindle. I should say, rather, my mother’s Louisiana records were not. She did have a collection of 45s and LPs she prided, and it was wildly varied, alive with cha-chas and merengues, bebop and West Coast jazz, and threaded through with r&b. She especially gravitated toward vocalists—Sarah Vaughan, Nina Simone, Carmen McRae—women whose voices sounded like big-city soigné, the women with drop-earrings-and-evening-gown voices who embodied an urban pulse that had entranced, and, ultimately, beckoned her.

But those songs she gave life to in the kitchen, that she’d learned from the radio or the recordings that spun on the front-room record player, had vanished: She’d lost her small collection “to Betsy.” I’d later learn that Betsy wasn’t a bully, let alone a person at all, but a weather event. The 1965 hurricane flooded out my grandfather’s shotgun house. In haste, he took piles of what was unsalvageable—records and clothes and photographs and yearbooks—and trashed them, then told her later. She’d left many of her adolescent mementoes in that little bedroom, a hide-away space that served also as my grandmother and great-grandmother’s sewing room. It was a big hurt that, even though she didn’t say it out loud, she never really got over. So while these Los Angeles gatherings would celebrate the moment, the vivid here and now, the turntable would turn out Memphis and Gulfport, Beaumont and someone else’s New Orleans. Later, the sky would deepen to violet, and if my brother and I were quiet enough, we could eavesdrop on the conversations that filtered in over a bump-and-grind or a grown-folks lament, from a vanished region that was someone else’s once upon a time.

What’s strange to me now as I revisit these moments is that I don’t have a memory of lacking anything, even without the presence of many physical records. There was sheet music in the piano bench, there was the jazz station on Sundays that used to work in New Orleans r&b tunes between the regular rotation of Muddy Waters, Bobby “Blue” Bland, and B. B. King. But it was mostly my mother singing her own New Orleans “hit parade”—Johnny Adams, Annie Laurie, Paul Gayten, Archibald, and, of course, Fats—broadcasting from her own frequency. This too is how I first got to know New Orleans; its geography; its rhythms; and its particular shade of laments.

When my mother set off for Los Angeles in the mid-1950s to begin college on a music scholarship, she was, by chance, on the train with one of her “hit parade” artists, Paul Gayten, the bandleader. Freshly out of the splash of the spotlight, he had just played a dance in New Orleans my mother had attended. The seating was less serendipity than mandated circumstance. The two of them sat in facing window seats on the Sunset Limited in the segregated Jim Crow car, casting off one last indignity: Gayten on his way to a West Coast gig, my mother on her way to her first Los Angeles address and all that awaited her—as my relatives would say, “across L.A.’s pearly gates.” I imagine the two of them in that swaying car, moving across that invisible yet ironclad Mason-Dixon Line, into their boundless future selves.

I was born way down in Louisiana,

I love the way it sounds,

... I live way out in California,

the folks are very nice,

but they don’t know about Louisiana…

—Percy Mayfield

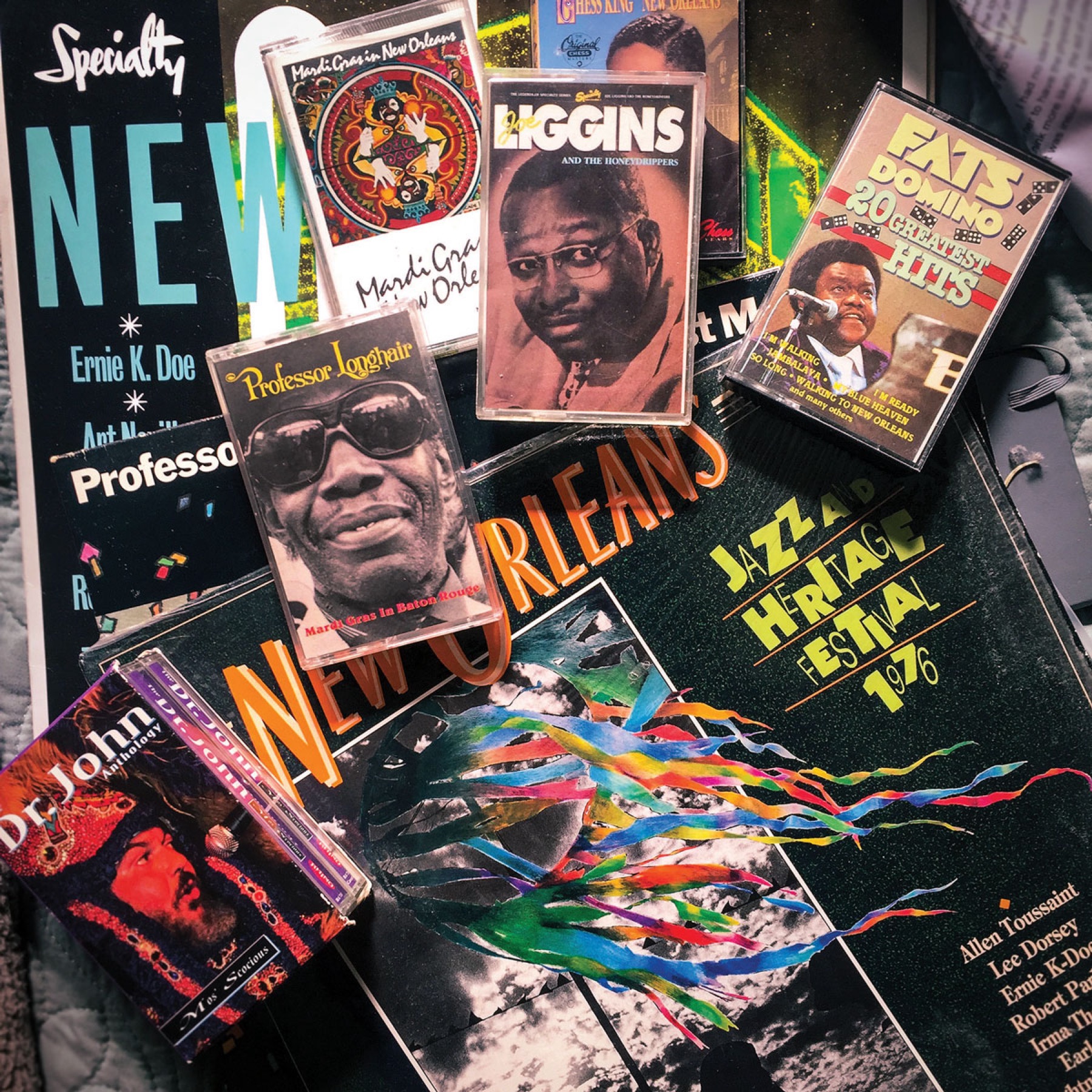

Music and memorabilia collected by the author's mother.

Who we become is shaped both by what we shed and what we keep. We memorize the essentials that we cannot physically carry. This thread of thought wound through me in my years-long process of making my way through my mother’s belongings after she passed away in 2009. Betsy may have “taken” some key keepsakes, but I unearthed an unexpected memory cache—some black-and-white snapshots, her high school diploma, bolts of my grandmother’s old fabric. Something that puzzled me, though, was a weather-safe storage bin packed full of music—cassette tapes and CDs—separate from her main collection that always sat next to the living room’s console stereo. I flipped through it with anxious fingers—stacks of classical music, jazz, contemporary r&b, and then a stash of New Orleans music, some of it still shrink-wrapped: Professor Longhair, Dave Bartholomew, Dr. John, Allen Toussaint, Louis Prima, Johnny Adams. Just looking at the titles brought her into the room. I heard the blues and “the blue” that made me blush fresh.

At first, I was flummoxed. It was all supposed to be gone, yes? But, looking closer at the familiar record store stickers, the price tags, I began to stitch together the how, the when, and a sliver of the why. During my adolescent years, when I was building my own collection—the Stevie Wonder, the Earth, Wind & Fire—she was just beginning to rebuild hers. Something must have both energized and delighted her to walk side by side with me, bend time, and revisit the person she had been at my age.

I had no idea how much she had worked to shore up those holes, or how much it meant for her to have the physical object, the document. Was she more homesick than I thought? Or, I think more likely, the act of collecting had more to do with building something to pass on. Maybe it was insurance, a promise to the future that we, her children, wouldn’t forget her South, but, even more, that we would find our way back to it.

I turn to the right

You find a little bright light

That leads you to my blue heaven

You find a cozy place, fireplace

A cozy room

A little nest that’s nestled where the roses bloom

—Fats Domino

When my mother boarded that westbound train, dreaming a future, I know she didn’t think she’d leave home for good. Consequently New Orleans never felt past tense inside her. Now, as an adult, when I wander through her old New Orleans neighborhoods as dusk descends, my ear trained to music floating out of bedroom windows, or find myself pulled in by the undertow of a neighborhood second-line beat on a Sunday afternoon, it’s as if I have never not been here—in this ongoing moment.

To find this secret stash felt nothing short of magic. I carried the prize—carefully strapped in like a passenger—across town to my own sunny Los Angeles home, where I now also keep watch on the yellow pot. It’s all there waiting for me: when I am ready for the floors and walls to fall away; when I want to travel back to once upon a time. I can be here and there, at once. Wistfulness, I’ve come to know, doesn’t go away. It’s passed on, an inheritance like a cache of records, like a recipe that you must commit to memory, like a patois you grow into. You can summon it, whenever you need it, from the deep, the major and the minor, the bitter and the sweet.