Alvin Ailey Finds His Voice

By Mark Burford

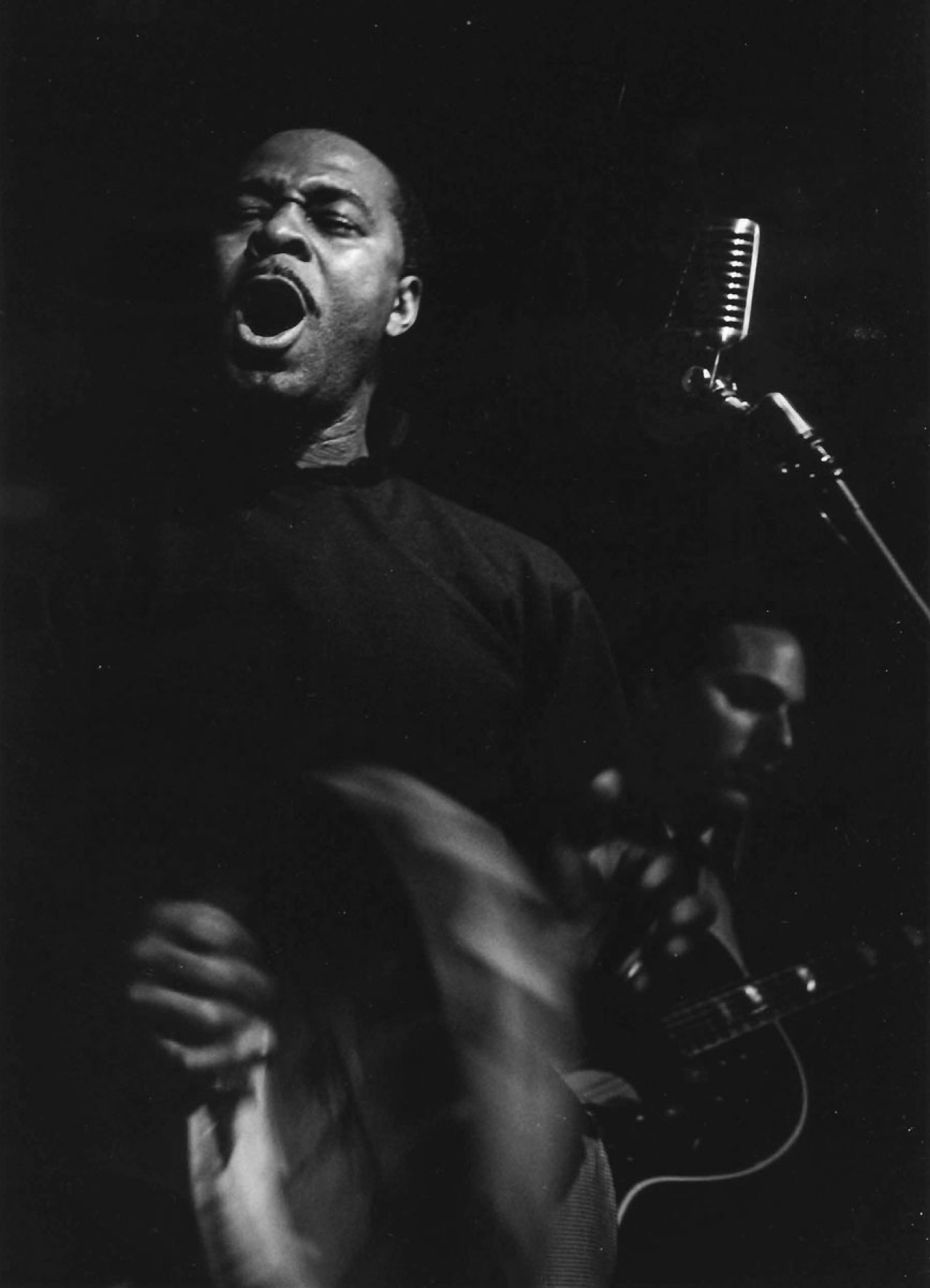

Brother John Sellers performing at Gerde's Folk City on May 24, 1964. Photo by Irwin Gooen. Courtesy Mitch Blank

Sometime during the early months of 1961, Alvin Ailey, a thirty-year-old African American dancer and aspiring actor, walked past Gerde’s Folk City—the New York venue Bob Dylan called “the preeminent folk club in America”—and was stopped in his tracks. Ailey was heading home from rehearsal for the William Saroyan play Talking to You at the East End Theater four blocks away: “I used to go through Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village to get to the subway, and one day I passed by this club called Folk City and heard a voice singing ‘[In the] Evening When the Sun Goes Down,’ one of my favorite blues songs.” The voice belonged to John Sellers, a Mississippi-born migrant to Chicago, who, following the example of gospel songster Sister Rosetta Tharpe, added “Brother” to his stage name. He eventually found his way to New York, where he became a fixture at Gerde’s as both a performer and an emcee.

A frumpy cabaret tucked on the corner of West 4th and Mercer Streets, Gerde’s brought together bohemia and the blues, booking the likes of Dylan, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, and John Lee Hooker alongside local favorites for patrons who ate, drank, smoked, and sang along from the club’s densely packed tables. Ailey vividly recalled the night he heard Sellers: “I said to myself, ‘Who the hell is that singing?’ I started stopping by the club all the time to listen to Brother John sing.” The back-home familiarity that Sellers’s sound summoned for Ailey, who was raised in southeast Texas about fifty miles south of Waco, harmonized with the vision that he was eager to pursue in original pieces for his new dance company, works weaving together his choreography, his attraction to theater, and the memories conjured by Sellers’s voice—above all, the landmark Revelations.

The historical importance of Revelations is secure. It has become the best-known—surely the most-watched—American concert dance of all time, performed continuously by Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT) for sixty years. For many of the countless millions who have seen the dance, its images and choreography are indelible; the huddled bodies, individuated yet allied, with outstretched arms and splayed fingers in its incantational opening scene, conveying a sense of shared history and collective aspiration, come quickly to mind. But Revelations is also haunted by voices, voices that remember, admonish, implore, testify, and rejoice. Built around sequences of African American religious songs—including two in the final section sung by Sellers—the work, as Langston Hughes described it, “explores motivations and emotions of American Negro religious music.” Even more, it is a work that pointedly brought to audiences across the country and around the world rituals of a Black South embraced by many as a point of origin. For a cohort of race-conscious African Americans who got to know the work in the 1960s, the sight and sound of Revelations were a powerful cultural-political touchstone. Robert Maurice Riley’s review of a 1974 performance, written for the New York Amsterdam News, took a personal turn to convey to the paper’s Black readership Revelations’ spirit of convocation. “On these special evenings, and you are Black, and you are sitting proudly in the City Center Theatre,” Riley reflected, “you say quietly to yourself (Some have even said it aloud!), ‘Umm-hmm. This is me. This is where I come from.’”

Bookended by these generative encounters—Ailey finding a voice resounding with Black vernacular sensibilities and soul-era audiences empowered by music and movement that affirmed the distinctiveness of African American cultural expression—Revelations’ first decade as a concert dance was nourished by the meeting of two Black southerners whose work together bridged time and place, for each other and for generations to come.

Ailey’s “deepest memories” were of Rogers, the Texas town where he was born on January 5, 1931. With a population of nine hundred and covering a single square mile in Bell County, Rogers was home to Black residents who earned a tough living picking cotton during the week then blew off steam listening to bluesmen like Tampa Red and Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup at a local juke joint called the Dew Drop Inn. At the heart of Rogers’s social life, however, was the church. “It was the center of my community. The church was always very important, very theatrical, very intense,” said Ailey. “The life that went on there and the music made a great impression on me.” These spheres of Black life were distinct yet in constant dialogue, both in Rogers and in Ailey’s artistic imagination: “Many of the same people who went to the Dew Drop Inn on Saturday night went to church on Sunday morning. In dance I deal with these two very different worlds.”

At twelve, Ailey migrated to Los Angeles in 1942 when his mother, Lula Cooper, sought financial stability through work in the wartime aircraft industry. There he met Carmen de Lavallade, a high school friend and artistic partner with whom he moved to New York in 1954 to appear as lead dancers in the Harold Arlen and Truman Capote musical House of Flowers and to pursue new creative projects. In 1958, Ailey started his own company, for which he created Blues Suite, an ensemble dance that put him on the map as a choreographer. Within months of his chance encounter with Sellers at Gerde’s in 1961, Ailey went back to the blues, inspired by a “love affair I’ve always had with these songs,” and embraced the singer as a collaborating muse for a new work: “I told him that I wanted to do a dance called Roots of the Blues, and I would love to have him sing for me.”

Roots of the Blues premiered in June 1961 at the Boston Arts Festival as part of a panorama of twentieth-century American dance. A late addition to the program—identified only by the placeholder title “Jazz Piece” in advance publicity—Roots of the Blues was a pas de deux with de Lavallade that further explored “the pain, desolation, frustrations, heart-aches, lost-love and social discontent of the Southern Negro.” In each of the work’s five sections—“Waiting,” “Jack of Diamonds,” “In the Evening,” “Backwater Blues,” and “Mean Ole Frisco”—Ailey and de Lavallade danced to songs sung by Sellers. No documentation of Roots of the Blues has survived, but de Lavallade remembered the piece as Ailey’s “gem, his best piece” and the audience reaction as overwhelming: “the whole Boston Commons went cuckoo. We stopped the show.” For Ailey, the duet was in fact a trio: “We had with us in its creation the inspired singing of Brother John Sellers, who brought a truth and beauty to these marvellous songs.”

Sellers was born on May 27, 1924, in Clarksdale, Mississippi, to a mother who moved without him to New Orleans after the catastrophic 1927 flood, leaving him to be raised by his godmother who ran a brothel and rented out her property to traveling Black vaudeville shows. He was still a small child in the early 1930s when an aunt followed one of the well-beaten paths of the Great Migration and took him to Chicago, where, orphaned again, he was taken in by gospel great and New Orleans native Mahalia Jackson, whom he had admired from afar and met on the street while wandering the South Side. In effect, Jackson became Sellers’s surrogate mother as well as a formative musical mentor under whose tutelage he developed an open-throated, rhythmically driven singing style closely modeled on Jackson. Her first two singles, cut for Decca in 1937, included “God’s Gonna Separate the Wheat from the Tares” and “Oh, My Lord” (aka “Sing On, My Singer”). When the twenty-year-old Sellers made his own studio debut eight years later, he sang the same two songs back to back, making his first record a two-sided cover of Jackson’s debut. As Chicago engagements became too numerous for Jackson to handle, she sometimes sent Sellers as a sub. The first version of Jackson’s breakthrough megahit “Move On Up a Little Higher” was in fact recorded in 1946 by Sellers, who surely plucked it from Jackson’s song list. But unlike Jackson, who conspicuously rebuffed invitations to sing the blues, Sellers had no qualms about Black popular music. Forging an independent career in the decade after World War II, he recorded alternately as “Brother John Sellers” and “Big Johnny Sellers,” cutting tracks that toggled back and forth between venerable church songs and the latest rhythm and blues, from “Pilgrim of Sorrow” and “Precious Lord” to “Busy Bootin’” and “The Right Kind of Loving.”

In the mid-1950s, Sellers, billed as “Mahalia Jackson’s protégé” and “a lusty singer of deep south songs,” caught the folk revival wave in Chicago and began to repackage himself as a folk singer. If Saturday night belonged to the blues and Sunday morning was gospel time, Mondays were set aside for folk music. In 1953, Sellers, still only twenty-eight, joined the cast of the Studs Terkel–hosted weekly folk song floor show I Come for to Sing, presented Monday evenings at Chicago’s Blue Note nightclub. Meanwhile, in New York, Monday nights at Gerde’s were becoming a magnet for folkies drawn to hootenannies hosted by the now-relocated Sellers, who juiced the crowd by dispensing hand-clapping gospel numbers and vestigial blues of the kind that caught Ailey’s ear. Whether because of stylistic continuities across genres or his own enterprise, Sellers, well before his long association with AAADT, had established his brand as a flexible vocalist capable of giving voice to an array of African American song traditions.

Despite his carefully cultivated success, a slight shade of skepticism always seemed to follow Sellers. Chicago was the preeminent Black gospel town, bursting with dynamic soloists, quartets, and groups. A base of operation for Thomas A. Dorsey, who was the musical and entrepreneurial face of the emerging interwar modern gospel song movement, and home of the pioneering choirs established in 1932 at Ebenezer and Pilgrim Baptist Churches, Chicago boasted a thriving scene as notable for competition as for camaraderie. On a given night in the 1950s, one might hear Jackson, Sam Cooke with the Soul Stirrers, or the Caravans with Albertina Walker and James Cleveland—perhaps going toe to toe on the same program. Some gospel singers there, already dubious about his fence-straddling, looked askance at Sellers, believing his choice opportunities came not from distinctive talent but because he feasted on crumbs from Jackson’s table.

Similarly, in New York, certain members of the Gerde’s crowd, particularly young white male musicians who studied hungrily at the feet of older Black master practitioners like Mississippi John Hurt and South Carolina native Blind Reverend Gary Davis—singer-guitarists whose careers were resurrected by the 1960s blues revival—also had their doubts. “I never took Brother John Sellers very seriously as an artist, to be truthful,” banjo player Dick Weissman mused, remembering Sellers’s reception among a circle of Gerde’s regulars who found his act to be less rootsy than shtick. “I think part of the problem with Brother John is that a lot of us…were really into Gary Davis and Gary Davis seemed to us to have, I don’t know, a lot more soul, a lot more to offer.” Sellers’s most valuable capital may have been his skill as a Black vernacular musical pharmacist willing and able to fill whatever prescription crossed his counter, though for some observers his cultural fluency veered dangerously close to inauthentic stylistic promiscuity.

But if Sellers-cynics detected self-conscious mannerism, Ailey heard true grit, “a Mississippian who sang the blues with real dirt in his voice.” For Ailey, questions of style were secondary to the preeminence of place. Ailey’s deep emotional ties to what he often referred to as the “blood memories” of his Texas upbringing, choreographed in Roots of the Blues and Revelations, helped forge the most immediate and visceral attachment to Sellers, with whom he shared a “tremendous love for and respect for the music” that became “a very strong connection with them.” Mutual reminiscences of “holy roller” churches, street corner singers, and touring tent shows—both recalled seeing the Silas Green Minstrels as children—bonded the two men. Around the time they met, Ailey wrote the poem “John Sellers Sings” in tribute to his new friend and collaborator. De Lavallade, who described Sellers’s voice as “rooted in the earth,” noted the fortuitous timing of their acquaintance: “It was where Alvin wanted to go. He wanted to do all the things of the South.”

Photo by Jack Mitchell from Alvin Ailey’s Roots of the Blues. From left to right: Carmen de Lavallade, Brother John Sellers, Alvin Ailey, and Bruce Langhorne © Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation and the Smithsonian Institution

A forerunner of Ailey’s celebration of southern Black life was Zora Neale Hurston’s 1932 folk concert “The Great Day,” a snapshot of an African American community at a southern Florida railroad camp. Not strictly a concert dance, “The Great Day” staged Hurston’s anthropological and folkloric research by blending spoken dialogue, music, and Hurston’s own choreography. The performance anticipated Blues Suite and Revelations most notably through the inclusion of sung spirituals, a section featuring a sermon by an itinerant minister, and a scene set in a local pleasure house reminiscent of the Dew Drop Inn.

Ailey “did extensive research, listened to a lot of music, [and] dug even deeper into my early Texas memories” to create Revelations, which premiered at Kaufmann Concert Hall in New York on January 31, 1960. Because of the costume colors, Ailey dancers commonly identify the three major sections of Revelations—“Pilgrim of Sorrow,” “Take Me to the Water,” and “Move, Members, Move!”—as the “brown section,” “white section,” and “yellow section,” respectively. Each is choreographed to a short set of songs. A supplication for spiritual liberation, “Pilgrim of Sorrow” is set to the spirituals “I’ve Been ’Buked and I’ve Been Scorned,” “Didn’t My Lord Deliver Daniel,” and “Fix Me, Jesus.” Ailey’s inspiration for “Take Me to the Water” was his memory of watching baptisms in Rogers. “I was held spellbound by the swaying of white garbed acolytes, going to the river to be submerged and born anew,” Ailey recalled, and the section features “Honor, Honor,” “Wade in the Water,” and “I Wanna Be Ready,” the latter a gripping solo for male dancer.

Originally a sixty-five-minute ballet, too long for a program of other works, Ailey trimmed Revelations to the thirty-minute suite known today. The most comprehensive change in the condensed version of Revelations was a radical makeover of the now famous yellow section, danced to live music to accommodate the presence of Sellers. None of the songs from the 1960 premiere of the concluding “Move, Members, Move!” were kept. Instead, it now began with “Sinner Man” and its tense warning of divine retribution. Added as well were two songs recommended and sung by Sellers—“The Day Is Passed and Gone” and “You May Run On for a Long Time”—chosen, Sellers explained, to capture “the way it’s done in the typical South today and in many of the smaller churches who keep up with the old traditionals around Chicago.” In present-day AAADT performances, Sellers continues to be credited as a co-arranger of these two musical numbers.

With its dynamic and diverse movement vocabulary, theatrical staging, live music, and more concise presentation, the revised Revelations was made-for-TV dance. On March 4, 1962, Revelations was broadcast nationally on the CBS Sunday morning program Lamp Unto My Feet, then the longest-running religious series on television. It was a coming out of sorts for the dance and a document of Sellers’s close work with the Ailey company. In Revelations, CBS advertised in major newspapers, “Spirituals and gospel songs and the dances they have inspired are brought together…against dramatic backgrounds of the Deep South.”

The climactic final section took viewers to church. As “Move, Members, Move!” opened on the black-and-white Lamp broadcast, the scene-shifting sound of gospel piano accompanied a close-up of a wood-framed church, further layered with barbershop-style banter by Black men’s voices calling on members to “Praise the Lord with the dance.” The camera finally settled on Sellers, dressed as a robed minister, standing solemnly and motionless at a pulpit with both palms resting on the lectern. With slight reverb adding a hint of gravitas to his voice, Sellers initiated the action by singing the brooding Dr. Watts hymn familiar among Baptists, “The Day Is Passed and Gone,” a lugubrious dirge backed by the harmonized moans of the off-camera Howard Roberts Chorale. The camera slowly pulled back to show the eight dancers, including Ailey himself, sitting on stools, fanning, rocking, and assenting as members of Sellers’s feeling-the-spirit congregation.

The meditative mood was broken and the dancers were set into motion by Sellers kicking off a new song, “You May Run On for a Long Time,” an up-tempo, jubilee staple popular among postwar male quartets. The tune was right in Sellers’s wheelhouse and the influence of Jackson’s gospel swing was on full display in the syncopated rhythmic play of Sellers singing over the song’s stop-time verses. Together, the two songs simulated an invocation and sermon; AAADT programs identify the latter as a “Preaching Spiritual.” Revelations concluded with the escalating jubilation of “Rocka My Soul in the Bosom of Abraham”—part modern dance, part country reel—sung during the broadcast by the Roberts Chorale, with Sellers as a soloist during the verses. The revamped “Move, Members, Move!” and the conspicuous showcasing of Sellers, the only non-dancer seen on screen, suggests that shortly after meeting the singer, Ailey, eager to incorporate his voice into Revelations, took Sellers’s recommendation of songs that would best enable him to do so and overhauled the final church scene accordingly.

The years following their appearance on Lamp Unto My Feet saw the Ailey company’s irrepressible rise from an exciting novelty troupe to a modern dance powerhouse. As the Sixties unfolded, AAADT built an international reputation through the rapturous response to their performances during high-profile tours of Europe, Latin America, Africa, and the Soviet Union. In 1962, the U.S. State Department, which had initially balked at a group “not of the caliber to bear any designation as the official representation from the United States,” sent the Ailey company on a fifteen-week, ten-country cultural diplomacy tour of Southeast Asia and Australia. Three of the works that the group took with them—Roots of the Blues, Revelations, and a new folksong-based dance created by Ailey especially for the tour, Been Here and Gone—featured Sellers singing onstage, playing prescribed characters in each theatrical setting. Sellers’s tightening bond with the Ailey group was evident when the company performed their State Department repertory in advance of the trip, billed in the concert program as “The Alvin Ailey Dance Theatre starring Carmen de Lavallade and Brother John Sellers.” Ailey consistently programmed the work of other choreographers, and he composed dances to music ranging from Duke Ellington to British composer Ralph Vaughan Williams to singer-songwriter Laura Nyro. Propelling his success in these early years above all, however, was the reception of Revelations, a work critics were already hailing as Ailey’s “masterpiece” and the company’s “signature dance.”

Far from transcendent art, Revelations was deeply enmeshed in its dynamic historical moment. As the influential critic Clive Barnes observed, times were changing, as modern dance in the U.S. for the first time witnessed the emergence of a small handful of “super-companies,” led by Paul Taylor, Merce Cunningham, Martha Graham, and Ailey. “The growing popularity of modern dance, coupled with the growing interest in black artists,” another writer noted in 1970, uniquely set the stage for Ailey. AAADT’s commemoration of the African American experience resonated with the late-Sixties soul era and Black Arts Movement, rooted in a cultural pride and racial consciousness that were a call to arms and a shout-out to Black audiences from within even mainstream popular culture. If concert dance retained its reputation as an elite white institution, Ailey and his dancers staked their claim as African American culture bearers, appearing on the Black-targeted public television shows On Being Black, Like It Is, and Soul!. On the enormously popular Soul! in 1974, during a special episode titled “Alvin Ailey: Memories and Visions,” Ailey was unequivocal both about his origins—“I’m a black man whose roots are in the sun and the dirt of the South”—and about the centrality of the blues, the gospel church, and the voice of “the incomparable Brother John Sellers” to the artistic vision of his southern-themed works.

At the same time, whatever the perceived singularity of the Ailey company, “Black dance” was still under negotiation. In the late Sixties and early Seventies, Black dancers and choreographers were actively theorizing and organizing, seeking to establish equal standing within the broader professional dance field while also determined to build autonomous institutions that would support culturally relevant domains of practice and criteria for evaluation. “What is and/or can be the role of dance in our Black world?” the Black dance newsletter The Feet asked in 1970. “What is the role of the dancer in the up and coming, already existing situation that we as Black people live in today?” For Ailey, dance theater held the potential to mobilize individual and shared memories of “Black roots” in the rural South. But the particular contribution of Revelations is brought into focus when the work is considered in counterpoint with alternate approaches to “Black dance” taken by Ailey’s accomplished, if less visible, contemporaries. These included such dancer-choreographers as Arthur Mitchell, whose Dance Theatre of Harlem was founded, somewhat controversially, to wed Black bodies and classical ballet technique; Eleo Pomare, who sought to document the stark realism of modern Black urban life from the inside and on its own terms; Rod Rodgers, who, determined not to be a “professional black man,” pursued non-representational abstraction unbeholden to “simplified traditional images”; and Katherine Dunham and Babatunde Olatunji, for whom Black dance was inescapably Afro-diasporic dance.

Understood in this context, the meteoric success of the Ailey company raised pressing questions within African American dance communities about the politics of origins and of audiences. African traditional dance and Afrocentric thought were at the height of their popularity in the late 1960s, making Ailey’s explicit claiming of the U.S. South as a Black homeland a distinct, perhaps even maverick, vision for its time. The subject matter, staginess, and eclectic technique of many Ailey dances enhanced their accessibility, a feature of Revelations that was occasionally received with some ambivalence. AAADT’s “dazzlingly theatrical and popular” style offered “dance for audiences that assuredly don’t like dance,” an otherwise supportive reviewer conceded. “The purists get uncomfortable. The audiences inevitably cheer.” The Colombian-born Pomare, who professed, “I don’t create works to amuse white crowds, nor do I wish to show them how charming, strong, and folksy Negro people are,” expressed his own skepticism of the crowd-pleasing “romanticism” of works like Revelations: “I have deliberately stayed away from Ailey’s concerts for years, because I am not so interested in the ‘razzle dazzle’ commercialism.”

Ailey held that the cross-cultural appeal of company repertory based on memoires of his Texas upbringing was a strength. Even as leading advocates of the Black Arts Movement, like theater scholar Larry Neal, called for “art that speaks directly to the needs and aspirations of Black America,” with an aesthetic grounded in “a separate symbolism, mythology, critique, and iconology,” Ailey insisted that Revelations “speaks to everyone,” despite the specificity of its cultural reference. “There’s nothing blacker than the blues,” Ailey told Soul!’s viewers, and yet “blues are global and universal.” With white critics fond of casting Pomare as the angry Black man of modern dance, their praise of Ailey’s integrated company could sound like a proxy rebuke of Black nationalist politics. Ailey “is no black apostle of apartheid,” wrote an approving Barnes, “and I love him for it.”

Still, for many African Americans, Revelations extended an invitation to self-recognition in spaces where they were too infrequently recognized. Whatever the reception by white audiences, Riley’s review of AAADT’s 1974 season at New York’s City Center acknowledged the pride and catharsis of watching the company. Riley was attending a special Ailey concert titled “In the Black Tradition,” which he described as “an entire two hours of dance that relate directly and specifically to ‘The Black Experience.’” He reveled in the thrill of a whole program featuring nothing but Black choreographers, including Pearl Primus, Donald McKayle, and Dunham, as well as the live music in Ailey’s own Blues Suite and Revelations. “Then you hear the ‘down home’ voice of Brother John Sellers singing the Blues and ‘Holy Spirits’ with clarity and verve,” Riley concluded, “and when you hear ALL this, I’m afraid you don’t give a damn whether the OTHER people in the audience understand it or not.”

By 1964, Ailey had added Sellers’s voice to his first blues-based dance and one of his most programmed pieces, Blues Suite, which in tandem with Revelations solidified the connection of Sellers with the company over the course of their nearly forty-year relationship. Sellers continued to perform live with AAADT off and on into the 1990s, though his voice was more and more often heard recorded. But for the company’s major events—their first Broadway appearance at the Billy Rose Theater in 1969, their Lincoln Center debut in 1974, their participation in Jimmy Carter’s presidential inauguration gala in 1977—he was a fixture. With his confidence perhaps boosted by affiliations with better-known stars—among them Jackson, Dylan, and blues musician Big Bill Broonzy—Sellers never lacked a sense of self-importance. In future years, he haggled with AAADT over intellectual property disagreements, having claimed, “I laid out the outlines of Revelations.” He told an interviewer that Gerde’s and the blues revival circuit in Europe had made him “famous” but he “gave all that up” to help a fledgling dance company at a time when the public didn’t “know nothing about Alvin Ailey.”

A more measured assessment is that Sellers’s close association with Ailey helped to reboot his reception. Despite listeners who perceived something studied, affected, opportunistic, or even second-rate in Sellers’s vocal performances, hearing his voice as part of Ailey’s documentation of the Black experience helped make what may have seemed bygone and remote feel proximate. “Within the black dance cultural world in New York, everybody knew Brother John. Everybody knew him. He was tremendously respected,” Ailey biographer A. Peter Bailey said in 2011. “He was a legend because he was connected with Revelations. Everybody who went to Revelations heard him sing.” Bailey recalled how he and his peers embraced Sellers as an elder, as a living link to a southern past memorialized in Ailey’s work, who corroborated cherished beliefs about Black music: “He was that person who knows how to do the gospel and the blues because they come out of almost the exact same source, one religious and one secular. And he could do it as well as anybody I had ever heard.” Sellers’s canny triangulation of performance personas—embodying Saturday night, Sunday morning, and Monday night—paid off, both as a career strategy and as an asset in Ailey’s exploration of interwoven Black vernacular musical traditions through dance theater.

The staying power of Revelations as an iconic American dance might be explained by how it sits at an ambiguous intersection of testimony and mythology. Citing memories and visions of people, places, and rituals he had personally known, Ailey crafted a form of storytelling through images, movement, and music that could bear witness to the rural southern culture of his youth for New York audiences. Notably, Ailey, like Hurston, sought to represent a distinctively Black South that flourished and aspired beyond the gaze and narratives of white southerners. It is also provocative to register that Ailey’s southern memories were voice-shaped. For most, Sellers is but a footnote, if that, in the story of the Ailey company, one of their many collaborators over the years. But the visibility, longevity, and priority of his presence in AAADT’s southern repertory indicate the intimate relationship between voice and memory for Ailey.

The mobility and archival span of Sellers’s singing—doing gospel, doing blues, doing folk—and even the variance in what people heard when Brother John sang, suggest a sense of voice that is less about a stable presence than a space of possibilities. Inspired by memory, Revelations serves up a delicious fantasy in which we are immersed in dance but also in ideas about southern Blackness, whether romanticized or politically potent. It was perhaps the fluidity and capaciousness of voice as practiced by Sellers—at once authentic and plastic—that enabled Ailey to hear the particularity of his origins while also imagining Black dance with a universal outlook.