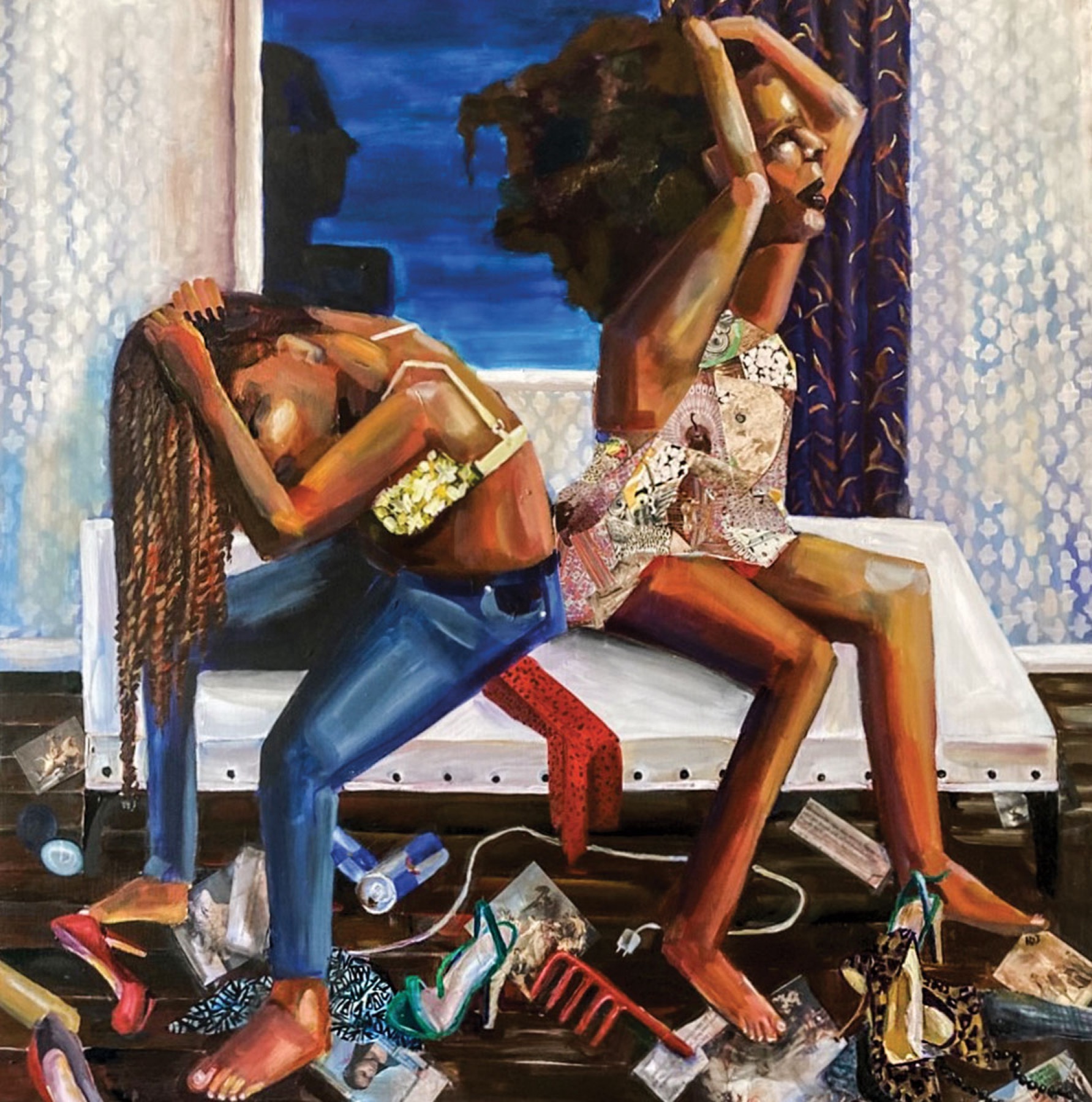

Night Air, 2017, acrylic collage on panel by Angela Davis Johnson. Courtesy the artist and Mosaic Templars Cultural Center

Overnight Scenario

By Karen Good Marable

I am at the club before my mother’s tears are dry.

Me and my nine-girl crew slink in a single-file line through an ocean of Black bodies. EPMD’s “So Wat Cha Sayin’” got us feeling subterranean; the air is thick with the heat of rhythm, style, and so much swagger. We’re headed to the front of the WUST Radio Music Hall, snaking our way toward the stage. The party is packed so we stick close, even when someone sexy holds a glance, touches an arm, mouths Let’s dance. We smile and keep on moving, straight ahead until a space presents itself and we plant our flag, circle up in the way girls do, dance with ourselves. The DJ is taking us higher and we raise our hands, surrender to the get-down, laugh and give dap like we’ve known each other forever even though we just met today. Here’s to new friends, tonight is kinda special. We done made it to the Mecca.

My family’s hajj had begun three days earlier when we packed our light blue Buick LeSabre so fully, I straight up could not see my brother, David, who sat beside me in the backseat. Before we pulled out the driveway, Daddy popped in his favorite (and only) cassette, Aretha Franklin’s Who’s Zoomin’ Who?, and we began our journey east from my hometown of Prairie View, Texas, upsouth to Howard University. First stop was Port Arthur, Texas, at my Aunt Nita’s house. She had barbecue chicken, potato salad, and baked beans waiting and made a toast in my honor. The next day we drove to Atlanta, Georgia, where Aunt Tina whipped up a dinner of green beans, yellow rice, and baked chicken and Uncle Billy told me, “Don’t call my house asking for money.” On the third day, after almost ten hours on the road, Mama was so sick of being in the car, she demanded my father find the nearest Holiday Inn in Alexandria, Virginia. Early that next morning, we motored into Washington, D.C. Daddy navigated Pierre L’Enfant’s byzantine streets while Mama gazed out the window. “I can’t believe I’m about to leave my child here,” she said, voice breaking.

In her defense, D.C. really was a different world. This wasn’t the rural town I was raised in, where one could hear a nighttime chorus of katydids and crickets, or the echo of the college drumline practicing across the fields. Across the street from my house, children played baseball in the same space bluebonnets and honeysuckle grew wild. There was one gas station (Leon’s), one convenience store (Super Save, which kept glass jars of pickled eggs and pickled pigs’ feet on the counter near the cash register), and the nearest McDonald’s—built two years before—was five miles away. I’d longed to live in a city, a place where there was more to do. I begged my parents to let me move to Atlanta and live with my godsister, Phyllis, or to Houston and stay with the McGees so I could attend HSPVA (High School for the Performing and Visual Arts). Mama wasn’t having it. But Daddy had already given me the keys to the kingdom. “You can go to any college you want to,” he’d been saying since I was knee-high to a bullfrog. “That’s my gift to you.” Once I really started to think about college, I was clear. “I’m going to the Blackest college I can find the farthest away from home.” Mama knew I wasn’t staying home. She tried to sell me on South Carolina State, her and Daddy’s alma mater; Spelman, where there was family nearby; and Hampton, which had recruited young men from Mt. Corinth Baptist Church to play on the football team.

Ha.

My heart was set on Howard, the storied HBCU with the great journalism department that was literally a thousand miles away.

The LeSabre pulled up to 2455 4th Street, NW, also known as the Harriet Tubman Quadrangle or “The Quad.” As far as I was concerned, it was the promised land. We parked out front and joined the dozens of families unloading suitcases, bags, boxes, and crates out of their cars and into the freshman women’s dormitory. Upperclassmen in blue-and-white t-shirts and name tags sat outside the building behind fold-up desks and gave out room assignments. I was assigned to Wheatley Hall, named for writer Phillis Wheatley.

When it was our turn, my family and I loaded the elevator, pressed 4, then unloaded, taking a right and walking a few doors down the carpeted hallway. My heart was beating fast when I opened the door. Inside were two twin beds, two desks, and two closets separated by a window which faced a greenspace in the back of the building. Toilets and showers were down the hall, as was the pay phone booth. Coin-operated washing machines and dryers could be found in the basement. David plopped on one of the beds as I stood in the middle of the space pondering which side I was going to claim.

“Heyyyyy!” I turned to find a girl peeking in the doorway. She had short, brown cropped hair and a wide, winning smile. “I’m Camesha.”

“Hey, Camesha,” we said in unison. I took her in: tennis shoes, denim short overalls, gold hoop earrings, a gold necklace, and a yellow half t-shirt that matched her disposition. I liked her immediately.

“Where’s your room?” I asked.

“Come see.”

All of us crossed the hall and walked a few doors down to the end where Camesha introduced us to her parents and little sister. She was blessed with a corner unit, slightly larger and full of light thanks to two windows—one in the front, which showed the expanse of the campus, and one on the side, where you could see the Founders Library steeple and the shuttle stop.

“Girrrrrl, this is nice!”

“I knowww right?”

Camesha was from Silver Spring, Maryland, which she pronounced “Murrlyn.” I told her I was from Prairie View, which my scooped Texas tongue pronounced “Prayerview.” She was enrolled in the School of B(usiness); I, the School of C(ommunications). Her longtime boyfriend, Kenny, was a twin and played football, and she loved to sing and dance. While we spoke, our parents laughed easy, engaged in their own conversation.

“You should just be my roommate.” Camesha said this as if she’d been hit by the bolt of a great idea. “Neither of ours are here yet and we already know we get along.”

I didn’t even have to think twice.

We rushed down the hall giggling like eight-year-olds to clear the bright idea with the dorm monitor, and squealed when she gave us the green light. My dad and brother moved my belongings across the hall; our mothers helped us unpack. Clothes were put away, beds were made, and after a few hours, our families gave us tight, if not lingering, hugs and, for the first time, left us on our own.

Camesha and I ventured out to meet the other girls on our floor. They hailed from Long Island, Winston-Salem, Hartford, Oakland, and Brooklyn. We were all so different—funny girls, fashionable girls, girls with Jheri curls or slicked-back hair. Girls with curves, girls with glasses, and girls who put on airs. What we all had in common was we were new here. So when someone produced a flyer for a party happening that night at a club close enough to walk to, nine of us, including me and Camesha, hurried back to our respective rooms to get ready. I chose a white short set with green and black stripes, my Louis Vuitton belt (with Gucci on the flip), and black flats. I unbuttoned my sleeveless vest top just enough so my lacy red bra peeked through. Camesha bumped her stacks with a curling iron and slicked the tapered parts down with black Ampro Pro Styl gel. She put on jeans, her tennis shoes, a blousy button-down, and a burgundy lip.

We met at the elevators a little after 9 p.m. and headed downstairs, out the Quad. Up 4th Street, then a left on Bryant, past the radio station and the College of Nursing, and onto Georgia Avenue, where we encountered other packs of freshmen; women from the same floor no doubt, headed to the party, or McDonald’s, somewhere together, grouped up in the name of safety, community, and belonging. It took about fifteen minutes to get to Georgia Avenue, then V Street, where we stood in line under the awning of the WUST, and didn’t mind at all.

Heavy D. is singing “Gyrlz, They Love Me” and I am throwing my whole body into the Wop. I’m swinging my arms with my fists balled up, whipping my shoulders, neck, and head left to right. I’m leaning in on one leg, backing up then shifting to the Cabbage Patch, stepping side to side. I’m dancing like nobody’s watching and like everybody’s watching, feeling like I’m back home at a party at the Newman center. My boy Maurice Swanson and I would be in the middle of the dance floor, snapping our necks from side to side to “Paul Revere,” jumping into a twist.

Tonight, Camesha and I are doing the Kid ’n Play, including stopping mid foot tap, holding hands, and hopping in a 180 before the step back-kick. Camesha starts doing the Reebok, and I pick it up; I break into the Robocop, and she’s right there with me. If one of us does a move the other doesn’t know, we observe the vocabulary, pump each other up—“Go roomie! Go roomie!”—then pick up the step. When the DJ plays Oaktown’s 3.5.7.’s “Yeah Yeah Yeah,” you can’t tell us we ain’t a part of MC Hammer’s crew, gyrating our bodies before breaking into the Running Man just like in the music video. We acting up, Camesha and I. Showing out.

I’ve been waiting all my life for a party like this. To be shoulder to shoulder with young, gifted Black people from everywhere, dancing in the dark to music I love and music I’ve never heard before. When “Voodoo Ray” and “You Used to Hold Me” come on, I study the footwork of cats from NYC, Chicago, and Detroit, whose movement seems a combination of African, breakdance, Nicholas Brothers, and zero-gravity. I scream as the entire club dances in slow motion to “French Kiss.” I stand back when “Pirates Anthem” and “Kuff” come on during the reggae set and the girls from up North ease out of the shadows like velociraptors and take center stage, winding their waists.

But nothing, NOTHING, compares to when the DJ plays this:

3 in the morning the pancake house!

4 in the morning we’ll be rolling to my house!

5 in the morning the lights go out!

6 in the morning you can hear her start to shout!

By the time the gruff emcee gets to 7 in the morning (she’ll be calling a cab), half the club, including Camesha, are shouting the lyrics with him like a live band is onstage, hands in the air. The already all-the-way-live party erupts and the beat hasn’t even dropped.

Oh, but when it does. When the emcee repeats the verse, which at this point feels more like a chant, and the drums kick in, it suddenly becomes very clear who is from the DMV area (DC-Maryland-Virginia) and who the fuck is not. Those of us who don’t know what’s happening, who don’t know this music, humble and brace ourselves. The moment is so pure and uncut, I dare not do a damn thing but stand still. I am hushed by the congas, silenced by the timbales, dared by...a cowbell? The song loops like a ring shout, like the refrain in a gospel song where the soprano, alto, and bass sections each have their say. I realize I am bearing witness to something precious, personal and homegrown. In this territory of less than seventy miles, shared by over fifteen colleges and the White House, the Black folks of Washington, D.C., let us know in no uncertain terms: This music belongs to us.

“Calling all dancers to the stage!”

The lights go up and the crowd turns to see a guy onstage who is not the DJ gripping the mic. “Calling all dancers to the stage for the dance contest!” Almost everyone in our vicinity looks directly at me and Camesha. I can’t even blame them. For the last two hours, she and I have been dancing like our names are Scoob and Scrap Lover.

“Y’all better go up there!” This from my traitorous fourth-floor Wheatley crew. If only they knew. For all my good-time-girl-ness, I do not like to be put on the spot. I’m kinda like Michigan J. Frog in the old Looney Tunes cartoons, the one who, when nobody is around but his human, pulls a top hat and cane out of nowhere and sings “Hello My Baby” like he’s performing on Broadway. Whenever his human tries to show him off though, Michigan just sits there and croaks. Before I can escape to the ladies’ room, my feet are suddenly off the floor and I am lifted onto the stage by some random guys. Camesha is too, along with four other girls. (No guys, because patriarchy.) Mortified, I steady myself, stand up and dare look beyond the lights into the crowd, which feels a little like staring into the sun. I turn to Camesha for comfort, but she, too, is facing front, smiling and bouncing from side to side like Mike Tyson.

The emcee spaces us ladies out, explaining he’s going to go down the line and each girl will dance to a clip of a song. After everyone has a turn, he’ll go back down the line and the audience will vote for each person by a round of applause. The person with the most applause wins. I look down at my shoes and take a deep breath, wishing I had worn my Filas instead of flats.

“DJ DROP THE BEAT!”

SAR-DINES!

HEY!

AND PORK AND BEANS!

A chorus of “Ohhhhh!” ripples through the watchers. Oh Lord, it is the sacred music of D.C. I am not ready. Not like this. Not like this.

The first girl gets her cue, and for about twenty seconds, thrusts her chest in and out to the beat, fists balled up like Rosie Perez dancing to “Fight the Power.”

The second girl plays it safe and does the Prep, cutting her hands back and forth through the air on her left side, then steps to the right and nods her chin with her hands on her hips.

To be honest, I barely notice the third girl, though I think she did some rendition of the Roger Rabbit. Ever been next in a Soul Train line and didn’t know what you were going to do? That was me. I’m searching so deep inside myself trying to find the groove, I’m squinting. Oh, how this music mocked me!

“Aiight Short Set, you up!”

The beat drops, all eyes are on me, and I do the only thing that comes to mind. I stand wide and, leading with my shoulders and twisting my wrists, snake my body down to the ground. When I’m in an impressive squat, I double-time snake to my left side, then to my right, then into a semi backbend before rising up. The effort is enough to garner a “WHOOO!” from the emcee, an enthusiastic clap from the audience, and a high five from Camesha.

Then...it’s her turn.

The music begins and Camesha looks the audience directly in the eye, smiling a smile that shows her teeth but is absolutely not a grin. Starting from the tips of her toes, homegirl begins bouncing her body, a simultaneous bounce-shake combination that looks effortless but is executed with a force far too intentional and punctuated to be taken lightly. In mere seconds, the people of the DMV begin to shout.

Camesha handles that shake like it’s a basketball and she’s a Harlem Globetrotter, first letting it live in her neck, then travel down her body, her shoulders, chest, breasts. She lets the shake dribble down her waist, plays with it for a second, then shifts the bounce from hip to hip like a belly dancer. This heffa then has the nerve to lean forward over onto one leg and let the shake bounce off her booty, hold it there, smile at the people, then shimmy the shake back up her body, where she just lets it ride. Oh my God. So mesmerizing, so dynamic is Camesha Antoinette Everett, the DJ just lets the music play. The music stops when she is done.

I look over at my new roommate like “WHAT???”

We all know damn well who won; still, the emcee insists on standing behind each of us like Kiki Shepard and letting the audience have their say. When he puts his hand over Camesha’s head, the applause is deafening. She beams, smiling that same winning smile I encountered earlier that day, and I am in awe of her. There is no prize but for the glory, and the five of us make our way off the stage. The same guys who threw me up there hold out their arms to help Camesha and me down and rejoin our girls. Like the Southern girl I am, I smile through my shame. I am not accustomed to losing dance contests, especially not on stage at my first college party in front of hundreds of people. I have not been this embarrassed since I fell down the stairs at the Astrodome during the Jacksons Victory Tour concert in ’84.

“OH MY GOD Y’ALL WERE SO GOOD!!!” Cherisse is gagging.

“I can’t believe y’all were on stage!” says Kenya.

“You could not have paid me to go up there!” Corrin says, shaking her head.

“Y’all were fucking amazing,” says Meredith. “Okay, I’m hungry.”

“Word.” Letania claps her hands. “Let’s go to Mickey D’s.”

Fall is coming; I can smell it as soon as we step outside. Soon it will be cool enough to rock the beautiful coats and chunky sweaters I earmarked in the pages of Essence or clocked Denise Huxtable wearing on The Cosby Show—clothing I have little use for in Texas. The nine of us walk down V Street talking about the party, who was cute, and how amazing the night was. But I am quiet. 3 in the morning the pancake house...is still playing in my head. I can still feel the slap of hands on drums; hear the call and response of the people; feel the earthquake that was Camesha’s bounce. The rhythm has burrowed itself under my skin, and I realize I don’t even know its name.

“Y’all.” I stop in the middle of Georgia Avenue and wait for my hallmates to slow their roll. “Can somebody please tell me what the fuck just happened?”

Letania cocks her head. “Huh?”

“The music in the dance contest. What was that?”

“You telling us you were onstage in a dance contest and you don’t even know what you were dancing to?” Letania got jokes.

“Yes. That’s what I’m saying. What was it?”

“Go-go?” Meredith looks at me under her glasses. I shrug.

“Go-go,” Camesha says. “You’ve heard go-go before! ‘Da Butt,’ ‘Shake Your Thang’ by Salt N’ Pepa…”

Ahhhh. I had heard those songs, and more. “Bang Zoom (Let’s Go-Go)” by the Real Roxanne. Grace Jones’s “Slave to the Rhythm”; “Don’t Make Me Over” by Sybil. Even “Words I Manifest” by Gang Starr, whose DJ—Premier—was from my neighborhood. In each of those tracks, go-go was the foundation, the bedrock, the hinge on which the door swung.

“It’s a D.C. thing,” Camesha says. “Tonight was the real deal. Rare Essence, Junk Yard Band.”

“What do they play in the clubs down your way?” Cherisse asks.

“First,” I say, “there are no clubs in Prairie View. But at the dances? Rap, soul, funk, slow jams. Not go-go. You see I didn’t even know how to dance to it!”

Meredith wraps one arm around my neck. “You do now, youngin!” she says like the D.C. folks, ushering me forward. “Welcome to Chocolate City.”