The Southern Roots of Q

By Terence Blanchard

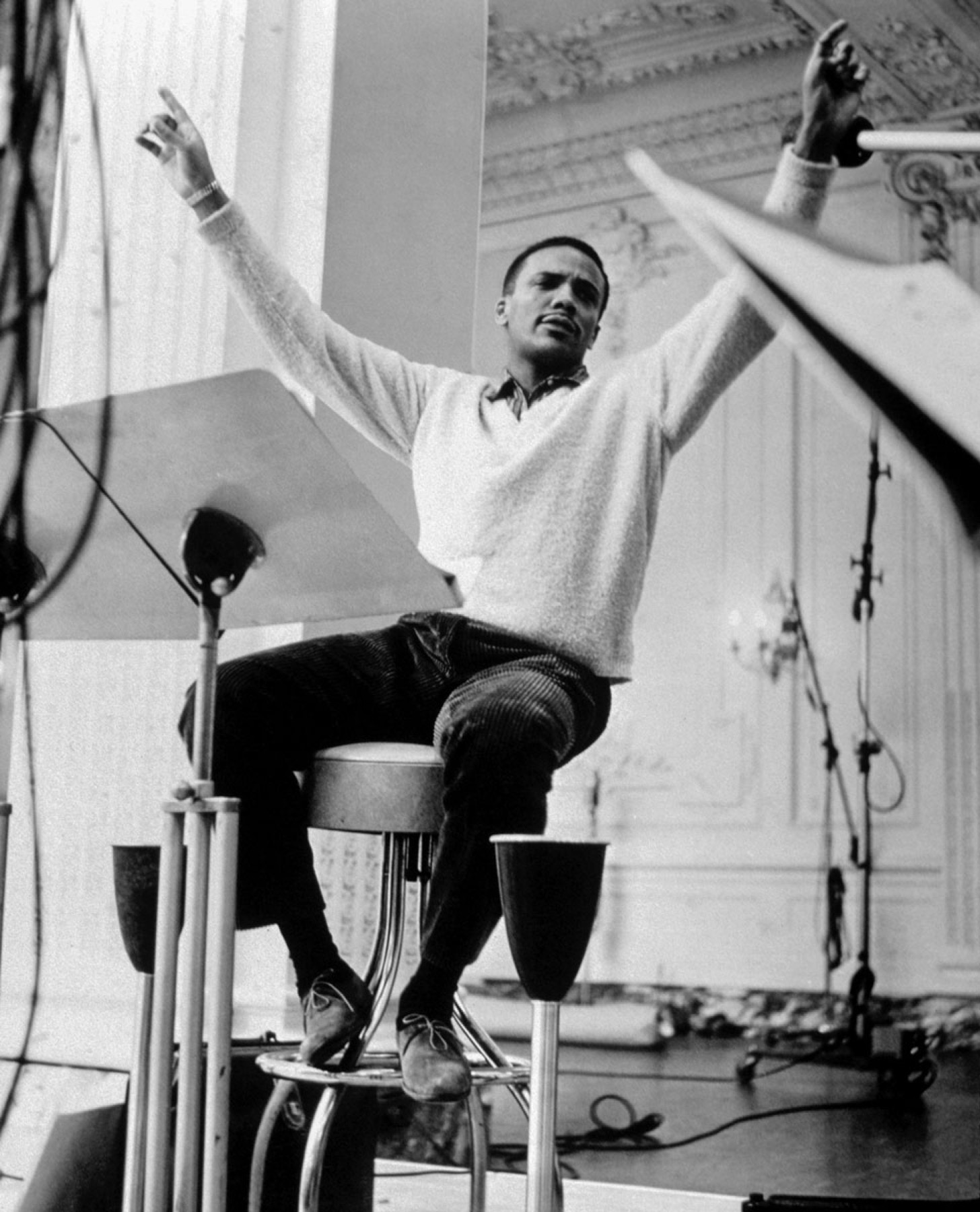

Quincy Jones, 1959 © Album/Alamy

Africans have been putting “groove” into improvisational music since before the forefather slave owners of these United States disenfranchised them as human beings in the Declaration of Independence, the Bill of Rights, and laws ever since. The American “blues” routes have gone from the Deep South upward through the Underground Railroad, the Great Migration, forced resettlement, and on, as you know. What I’m calling “blues” here is the massive bucket of a term for the musical genre that promises resilience in the face of hardship.

The great Q, Quincy Jones, was a kid in Chicago during the early 1940s—he was born there in 1933. In his biography Q, his childhood friend Lucy Jackson recounts playing jazz and more on the piano with young Quincy in her house. Still, the music was not his primary concern; that was idolizing the gangsters his dad carpentered for, and acting like a hoodlum, and then gangsterizing the hood. Quincy may have heard jazz on the radio, coming out of clubs, but more important, as “Little Lucy” recounts, were pint-sized thefts, like stealing watermelons and “put[ting] a hurtin’ on that melon” in the vacant lot that served as their ballpark. Quincy was tiny, but he and his younger brother Lloyd “ran with gangs and from gangs.” Music, in the background, on 78s, on Lucy’s piano, would later become an infatuation, his solace, his center, only after his dad moved the family as far away from the South as possible: to Sinclair Heights, forty minutes north of Seattle, after finding a job at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard.

There is a Southern influence to Q’s career. Still, you might not be able to define how or what that is, since Quincy excels at creating, producing, arranging, managing, directing just about any genre you may want to discuss. Look at his discography, filmography. Look at his awards and honors. Those go on for forty-three pages at the end of his biography. In small font. His filmography includes television appearances featuring cameos with Puffy, Wu-Tang, Diana Ross, and Michael Jackson—not at the same time, but wouldn’t that have been an interesting twist on a We Are the World, Part Deux? You may ask, as I often do, shaking my head: How can Quincy do everything great? Exceptionally great?

And here is what I think. I found it in Q’s bio as well. It is a quote forged by his father: a Black man, a man of few emotions and words—at least to his kids, and not when the belt was needed—like so many others of that generation, duty-bound while oppressed by circumstance and racial injustice and forever in poverty, paid minuscule wages for backbreaking work. Q’s father, also a Quincy, was raised in the South, Lake City, South Carolina; maybe. Q was never sure.

“Once a task is just begun, never leave it till it’s done. Be the labor great or small, do it well or not at all.”

The quote seems straight from the lives of the dirt-poor who needed youngsters to get the work done and done right. No time for a second chance, a redo. Focus. Do it right. And Q found out just how dirt-poor his grandmother was when he and his brother were deposited there in Louisville, Kentucky, after his mother’s breakdown, when Q was just seven years old. Their grandmother taught them to catch and kill rats. That was dinner, sometimes. Waste nothing, as “she had nothing to waste.”

Focus and use everything. The concept of doing it right and putting the work in to get it right seems to be the through line of Q’s career. This has to be how he has succeeded with almost everything musical placed under his care.

My father, Joseph Oliver Blanchard, sold insurance by day and sang opera at night. He was a music lover who enjoyed all types of music. He always encouraged me to aspire to the highest level of perfection. Whenever Oscar Peterson played on television, he would scream, “Come here, boy, and listen to this!”

And family. Family is a big part of Quincy—yes, ever-growing due to divorces and, well, anything snarky you may want to say leave it out there, but family, related and extended, blood and crony, friendships held together by a love of music. Q’s musical influence is broad and deep because of the family he has gathered around him and nurtured since he left Seattle for Boston and Berklee.

Quincy’s family and many low-income families (of all colors) in those decades were whirlpools of chaos: no money for anything outside of food, and then perhaps not even nourishing. Too many living under one roof, if that, in sub-standard housing ghettoized from the more affluent whites and, maybe by design, no safety nets. Q’s house was all negative energy, pulling, not pushing. His dad was distant, his stepmom antagonistic, his mother, not there physically and psychologically. There was no there to hang on to.

One day, peering into Dick Green’s Cafe, a jook joint in Sinclair Heights his daddy told him to stay away from, the music “hit my heart so hard,” Q said. “Washed over me with such a beautiful force, that I’d spend the next fifty-five years trying to get back to it.… There was a family in there. A family gettin’ down. I knew I belonged there.”

One fateful day, at the age of fourteen, I ventured out to play a gig in the Ninth Ward of New Orleans. I was in the horn section of an r&b band of grown-ass men. All of the older women thought I was so cute because I looked like a baby. The older guys propped me up with a beer to make me look like I belonged. They told me, “Don’t drink it, hold it.” On the break of the show, as the house music began to play, the song stopped all of a sudden and I heard an announcer say, “Terence Blanchard, your father is at the front door.” That was the end of the night for me and almost my music career. My father wanted to put me in boarding school. I shuddered to think about boarding school. I knew I wanted to be with those amazing musicians who played with soul and feeling.

Family is also the center of my life—a constant in my music career of variables. Family and friends help me navigate the difficult balance between relationships and my art. They inspire and focus my restless mind. They ground me when I lose my footing. Q, my fellow Piscean brother, has always been inspiring when I see him. He embraces me like family. And like family, he is quick to point out that his favorite arrangement of mine is one of his film themes from The Pawnbroker. Q telling me anything? Absolutely priceless.

Traveling north during the Great Migration was to place the horrors of the South far behind, but Paradise was hard to find in the North unless you discovered drugs, alcohol, sex, the VICES. Or wrapped yourself in the teachings of the Bible and the Golden Rule.

Or, you found sustenance, as Q did when he discovered a piano in a deserted rec hall. Joy. His addiction. Here he found a “feeling so good I couldn’t let go of it.” A paradise built by creating harmony, melody, notes, chords, and swing out of the dregs of your life. The great jazz musician Art Blakey used to tell me all the time, “Music washes away the dust of everyday life.” I think Q and I would agree about the exfoliating powers of a twelve-bar blues.