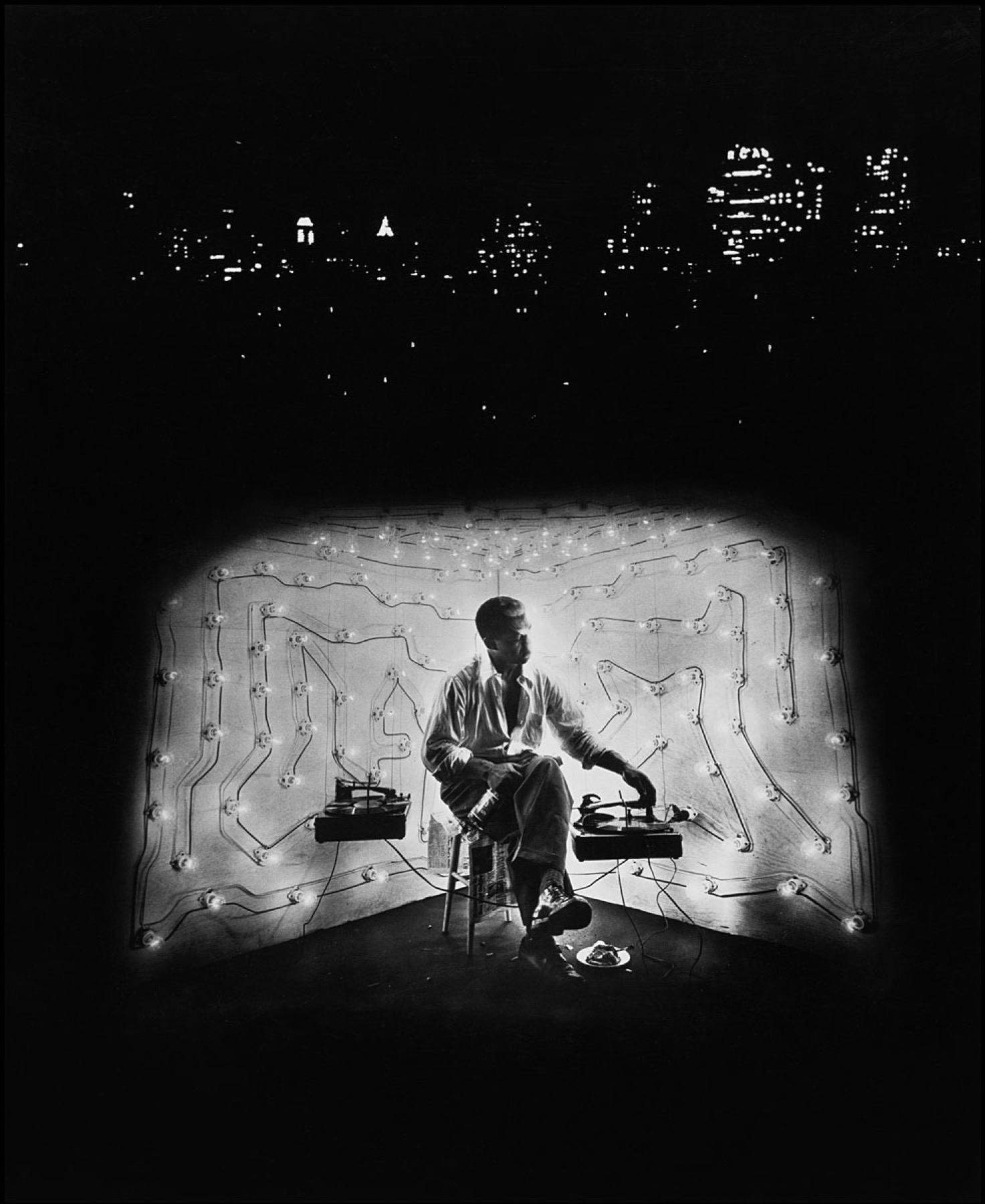

“Invisible Man Retreat, Harlem, New York,” 1952, photograph by Gordon Parks © and courtesy Gordon Parks Foundation

Where Is Jimmy Bishop?

By Alex Lewis

No one knows what happened to Jimmy Bishop. At least, no one will tell me.

I’ve heard from Jimmy’s family and friends that he was probably born in 1938 or 1939, somewhere in rural Alabama. He traveled north from St. Louis where he was a popular DJ at radio stations KATZ and KXLW and arrived in Philadelphia in 1963. At the time, radio personalities were celebrities, and he hoped moving to a bigger market would open new doors.

Jimmy landed a job at WDAS, the City of Brotherly Love’s most powerful Black radio station, hosting The Jimmy Bishop Go Show and spinning the latest hits from the Temptations, the Four Tops, and Dionne Warwick. Stations like WDAS were groundbreaking because the music they played and the voices they broadcast catered directly to Black audiences. On a typical day in the 1960s, you might hear the debut of the latest single from the Supremes featuring Diana Ross, followed by an exclusive live interview with Malcolm X, followed by a comedy set or a community forum. At the time, WDAS was the only place you could hear any of this.

As a record and concert promoter, the suave “Bishop of Soul” helped introduce Philly to artists like the O’Jays, Aretha Franklin, and the Jackson 5. And as a producer, he was an early architect of “The Sound of Philadelphia,” personally giving Rock & Roll Hall of Famers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff some of their first songwriting credits.

When I mention Jimmy Bishop to people who were his fans, I hear, again and again, some variation of this: “He was just cool.”

And then they ask me: “Do you know what ever happened to him?”

Jimmy Bishop (right) with Gladys Knight and Merald Knight Jr. Photo courtesy Jimmy Bishop Jr.

I learned about Jimmy in 2013 when I was invited to help write and produce a public radio documentary about the history of Black radio in Philadelphia. Going Black: The Legacy of Philly Soul Radio was about WDAS and WHAT, the first two radio stations that programmed for Black audiences in Philadelphia. Hosted by the legendary Kenny Gamble, who early in his career frequently collaborated with Jimmy, the documentary explored the birth and evolution of these stations in Philly, their influence on the rise of soul and r&b, and the roles these stations played in the civil rights and Black Power movements.

The format of stations like WDAS emerged on the heels of pioneering institutions WDIA in Memphis, the very first station to feature all-Black programming and all-Black on-air talent, and WERD in Atlanta, the first station owned and operated by African Americans. Inspired by the rapid growth of the Black population in Philadelphia during the Great Migration, a few progressive white radio station owners realized the massive potential for advertising dollars in this expanding audience. WHAT hired their first Black radio announcer in 1945—possibly the first in the nation—and six years later, WDAS switched their music mix and programming to cater to a Black audience.

I fell in love with radio at my college station. The physical aspects were what attracted me first: the dark control room, the weight of the faders, the library of records like a living history of music at my disposal. It was exciting to be given license to play an eclectic mix—Jason Molina, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Laurie Anderson, and New Zealand rockers the Clean—all during a single shift.

This initial spark eventually evolved into a passion for crafting audio documentaries that could tell stories through collected interviews, archival and field recordings, music, and sound design. A cliché among radio and podcast producers is that the intimacy of the medium makes it so powerful; the idea that the voices we broadcast are transmitted right into your speakers or headphones. But to me, the medium’s power lies in its boundlessness. Well-crafted audio can hold us in several places at once. It can transcend borders, power structures, and time. People long gone from this world can resonate in the present moment.

As a young radio producer, I had hours of fun listening to archival recordings of these pioneering on-air personalities who were championing the hippest music and redefining the medium so that it could bring joy, hope, and solidarity to a community that had been systematically oppressed and ignored by mainstream media.

But Jimmy Bishop was a mystery from the beginning. Although he had arguably been WDAS’s most important program director in its early days and a supremely popular on-air personality, our documentary team couldn’t find a single example of Jimmy talking live on the radio. We checked local and national archives, crowdsourced anecdotes from the public, and spent many hours digitizing cassette and audio tapes hoping to actually hear Jimmy doing his thing. While we were able to find recordings of even more obscure personalities, we were never able to find a single snippet of his on-air voice.

Samples of Jimmy’s style do exist, though. Search “Jimmy Bishop” on YouTube, and you’ll come across recordings of Jimmy the Impresario. For a time, he regularly hosted concerts at the Uptown Theater in North Philadelphia and the Nixon Theatre in West Philly, the city’s premier venues for Black performers.

In these recordings, his voice is warm and confident. He keeps his introductions brief, hyping the crowd up with a sentence or two (“How y’all feeling? Feeling good?”), saying just enough to introduce the act (“Here’s the Delfonics!” “The Ambassadors!” “Billy Stewart!”), and then moving out of the way to let the artists shine. He never lets down his icy cool exterior.

A comment on one of these YouTube videos from user HaysEaglets reads: “I still have the Saturday Night at the Uptown [vinyl] featuring The Drifters also hosted by Jimmy Bishop. Bishop just disappeared one day in the early 70’s & last I heard still hasn’t resurfaced. I did hear a rumor that he became a minister.”

In addition to rumors of a spiritual vocation, there’s also talk of the local mob, a payola scandal, or a gambling scheme. But it’s all speculation.

Louise Williams Bishop told me that she and Jimmy fell in love quickly after they first met. She was set up on a date with him soon after he arrived in Philadelphia, where she has lived since childhood. “He was not a real bubbly personality,” Louise said. “He was very quiet, but also very well spoken. He seemed to be sincere, a nice guy.”

Known as the “Gospel Queen of Radio” in Philadelphia, Louise Williams was the voice of Sunday mornings on WDAS. She would preach, read scripture, and play records from greats like Mahalia Jackson, Clara Ward, and Albertina Walker. She had actually gotten her start at rival station WHAT, hosting what she called a “sensuous program, sponsored by a wine company.” Eventually, Louise was persuaded by General Manager Bob Klein to join WDAS. She quickly became one of the top-rated and, thus, top-earning DJs at the station.

Louise told me that she introduced Jimmy to Bob Klein, and the men instantly liked each other. It took some time before Klein officially hired him, but eventually Jimmy was brought in to WDAS.

“He was young. He was articulate,” Louise said about his on-air style. “He was straight. He didn’t talk any jazz talk. He did a straight radio program with a restrained voice. He didn’t have some other made-up personality. He was himself.”

When Louise says “jazz talk,” she’s alluding to jocks like Jocko Henderson, one of the most popular on-air personalities in the early days at WDAS. He referred to himself as the “Ace from Outer Space,” and he was famous for rapping and rhyming on the radio: “Eee-tiddly-ock! Ho! This is the Jock, and I’m back on the scene with the record machine, saying oo-pop-a-doo, how do you do?”

The stars at most stations were the personality jocks who spoke to a common experience. They became role models and celebrities and broke Sun and Stax hits like Rufus Thomas in Memphis, or expanded opportunities for Black artists like Atlanta’s “Jockey Jack,” Joseph Deighton Gibson Jr.

“One DJ described it that he became a member of your family,” Portia Maultsby, an emeritus professor of ethnomusicology at Indiana University, told us for Going Black. “That his radio style was so personal that it seemed as if he was just in your home. And, again, he spoke the language that African Americans understood.”

In Philly, one of the most legendary moments on WDAS occurred on April 4, 1968. Georgie Woods, “The Man With The Goods,” broke the news on air that Martin Luther King Jr. had been assassinated and took live calls to give people an outlet for their grief and anger. This was followed by wall-to-wall gospel music hosted by Louise Williams. To this day, WDAS is given credit for the way it navigated that devastating moment.

Jimmy Bishop was “a less-is-more kind of guy,” Harvey Holiday, a good friend and colleague of Jimmy’s at WDAS, told me on a phone call. “I stole some of his lines—he could say a lot in five or six words. There’s nothing more boring than someone who makes their point and keeps talking. I learned from Jimmy to make your point and get the hell off.”

Harvey told me Jimmy did a recurring segment on his show where he played romantic songs and, in his low, rich voice, called himself “The Love Man, Jimmy Bishop.”

Harvey also loved to talk about how Jimmy was always late for his on-air shifts. He said Jimmy would multitask by eating in the studio while he was on the air: “He’d be having a steak. He’d have a four-course meal in front of him and he’d have two people on different lines. And he wouldn’t miss a beat. He would talk to whoever he was talking to, play a record, and then he’d take a bite of steak. He was amazing in that way.”

“He was a top man in Philadelphia, and I enjoyed it,” Louise said. “But he wanted to do what he wanted to do. And he had become so big that he felt WDAS was handicapping him. He had an image of becoming Berry Gordy grooming the next Diana Ross. So that’s the direction he was traveling in.”

Jimmy Bishop with the Temptations. Photo courtesy Jimmy Bishop Jr.

Jimmy founded Arctic Records in 1964. Prior to Arctic, he had been a partner in another label called Dynodynamic, but with his star rising at WDAS, he felt ready to strike out on his own. At Arctic, Jimmy wrote songs, oversaw the recording sessions, recruited, and even managed many of the artists.

While Arctic celebrated a few hits—perhaps most notably with r&b singers Barbara Mason (“Yes I’m Ready”) and Della Humphrey (“Don’t Make the Good Girls So Bad”)—the label’s legacy is defined by the young Philly-based talent it helped nurture: Kenny Gamble, Leon Huff, Harold Melvin, and Daryl Hall (yes, of Hall & Oates fame) all got their start at Arctic. It proved to be the training ground for Gamble and Huff’s Philadelphia International Records (PIR), which hit its peak about a decade later in the early 1970s. PIR went on to release over one hundred fifty gold and platinum records and provided a platform for hundreds of musicians in Philadelphia. (The history and significance of Jimmy Bishop’s Arctic Records is beautifully cataloged in Cooler Than Ice: The Arctic Records Story, released in 2013, which also includes the definitive collection of every single—including unreleased songs—that the label put out.)

Jimmy shut down the label in 1969, and no one knows why. But his knack for recognizing and managing talent was rewarded with a VP position at CBS’s publishing house, April/Blackwood Music, one of the biggest record labels in the nation. Tasked with recruiting talent, Jimmy introduced CBS to Gamble and Huff. The network went on to distribute PIR’s records until 1985. Jimmy had worked his way to the top of the music industry.

By this time, the marriage of Jimmy and Louise was on the rocks. They had four children together; their youngest, Jimmy Bishop Jr., is now in his early fifties. His father was usually out working when he was growing up, he told me, but he also has memories of celebrities constantly turning up at their house. “There was a time where, if you’re a Black artist, you didn’t come into Philadelphia unless you came to the house,” Jimmy Jr. said. “At the kitchen table could be anybody from Gladys Knight to Aretha Franklin to the Jackson 5. Al Green, Temptations. They were all in the house.” All these artists felt indebted to Jimmy and Louise for being among the first to break their records on the radio and help them land number-one hits.

“I’ll put it this way,” Jimmy Jr. continued, reflecting on his three decades of working in the same field as his parents. “For me, especially when I have to carry the name—it’s opened many doors. So, I’m grateful for the name. I’m grateful for the work he did. I was fortunate enough to follow in his steps for a nice long run. It’s something that came natural and it came easy.”

By 1971, Louise and Jimmy Jr. had more or less lost touch with Jimmy. “I had divorced or separated [from Jimmy] at that time, so he was not beholden to me to explain everywhere he was going or what he was doing,” Louise said. “So he went his way and I sorta went mine.”

Louise went on to become an ordained Baptist minister and served as a Pennsylvania state representative for more than twenty-five years. (She resigned her seat in 2015 amid corruption charges, but that’s a story for another day.) She continues to preach and play gospel music every Sunday on Philly’s WURD, doing what she has done for nearly sixty years.

I asked Louise if she would be interested in finding out what happened with her ex-husband: “I pray that he’s fine, that he’s happy, and that he’s doing what he wants to do, but I don’t have any desire to go meddling and try to find out. I’m still where he left me right here. I’m comfortable right here.”

One thing that fascinates me about Jimmy’s disappearance is that it would be impossible for someone with his public profile to vanish off the face of the earth in today’s world. There would surely be local news clips, social media sightings, tracking data on those creepy white pages websites. Something more.

A few people told me about encounters with Jimmy in the years after he left Philadelphia. Jimmy Bishop Jr. said they haven’t been in touch for about twenty years, but that his father used to occasionally check in on the phone and, on a few rare occasions, visit the city to meet his grandkids.

Harvey Holiday relayed the story of a sadder encounter he had with his old friend in the 1980s: “He called me one day, and he said he wanted to meet me. I met him at the Marriott [in Philadelphia]. And, I would never have recognized him. He had no teeth. If I didn’t know I was meeting him, I wouldn’t have known it was him. He’d been on a special kind of diet. He only ate fruit or something like that. And he asked me for a donation, which I respected cuz if he asked me for a loan, he wasn’t going to pay me back. So I gave him some money.” Harvey told me he had one or two more meetings with Jimmy like this, but that was about it. “So after that I heard he [was] running a gospel record label in Tennessee,” Harvey said. “And that’s the last I heard of him, roughly.”

If he’s still alive, Jimmy would be in his mid-to-late eighties. He’s been out of public sight for fifty years now, and there’s a very limited number of artifacts left showing just how talented he was. But Jimmy Bishop’s significance is felt in these memories shared, the stories people tell about him. And his signature “cool” style is imprinted in the DNA of the music and radio stations so many people still love. He was an early architect of a Black radio industry that has since been commodified, consolidated, and sold for billions of dollars.

But I also wonder: What if Jimmy just wanted to fade from sight? What is the point of searching for someone who doesn’t want to be found?

It’s in our nature to want to solve a missing-person mystery. But when people ask, “What happened to Jimmy?” maybe they’re mostly just asking for a way to express their gratitude for his gifts.

I asked Jimmy Bishop Jr. what he makes of people’s curiosity surrounding his father’s disappearance: “It kind of captures his whole concept: You gotta leave them wanting more. And he did that! He hasn’t been on the radio since the 1970s and they’re still talking about him....The conversation’s never stopped. It’s pretty amazing. God bless him.”

So if you’re reading this, Jimmy: Thank you. And, where are you?