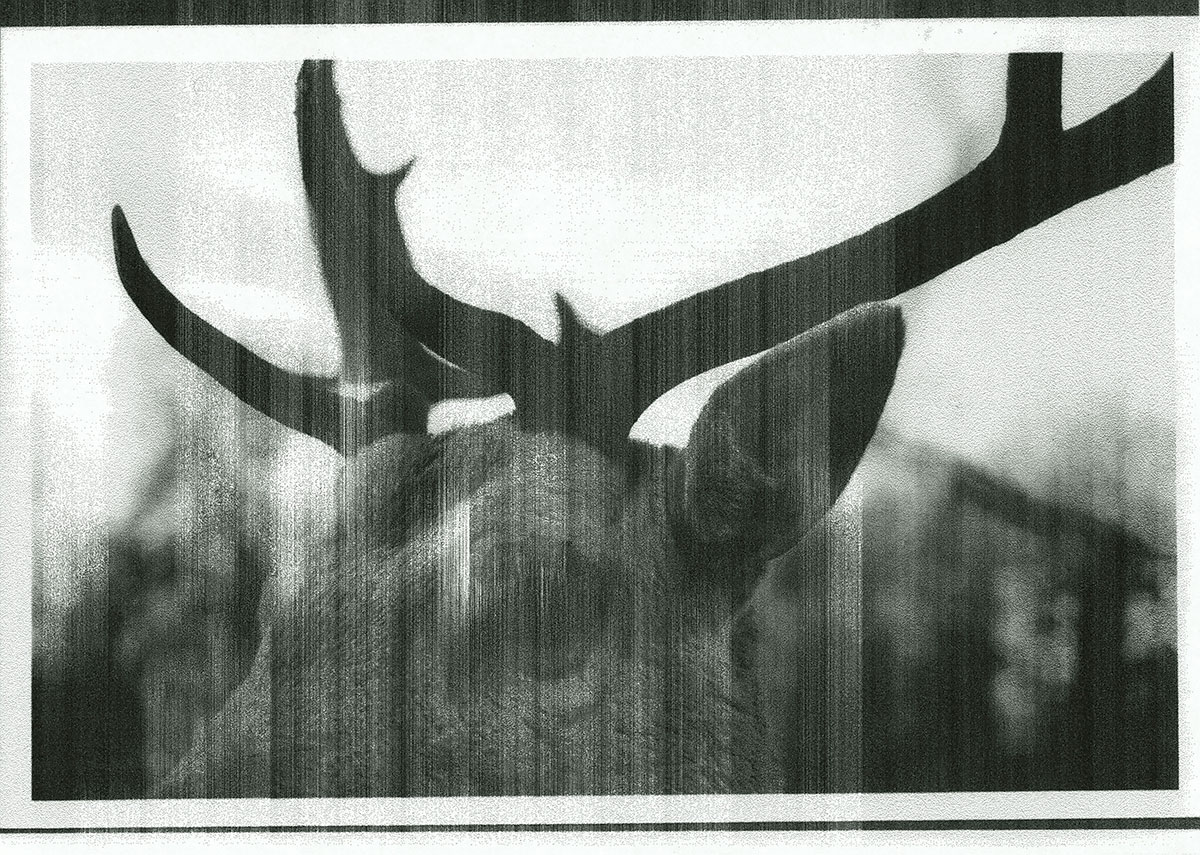

“Aaron mist,” from All That You Leave, by Luis Lazo. Courtesy the artist

Where the Animals Sleep at Night

By Meghan Reed

My five-year-old told me he was a Buddhist monk in his past life. I didn’t think much of it at the time. Kids, you know. He went into detail about his monastery in the mountains of Tibet, about his best friend, Akar, and the process of making tsampa and yak butter tea. When he told me this, we were eating breakfast. He shared a mantra with me over his oatmeal, Sanskrit floating off his tongue as he pushed away his tiny, tiger-shaped plastic bowl.

I asked him: “Excuse me, where does your bowl belong?” I wasn’t about to let him know I was terrified of him. His father had already gone to work so I had no backup; I knew the odds were stacked against me. What’s worse is for the past few months my son has been having sleeping problems. We’ve tried everything: sound machine, sleep sack, bedtime routine, sleep study, prayers of supplication to every god we could think of. This slip in reality could be related to his sleep deprivation. His mind was now going wild at the age of five—and so my mind was going wild at the age of thirty-seven. They don’t tell you about these things when you’re pregnant. They don’t tell you that your child can be a terror and you can’t send them back and ask for another one.

I have never really connected with my son the way a mother and child should. We have a strict business relationship—I make sure he stays alive, and he slowly wears me down year after year by revealing all my faults and innermost fears. It’s his father who’s the better mother—he’s the one who should have been pregnant with him. Oh, he would have melted every time Leif jabbed his side with his powerful baby fists and woke him up at all hours of the night. In all honesty, I just didn’t know what to do with Leif—he was so foreign to me. I didn’t understand him, even though he was my own flesh.

I wasn’t the one who particularly wanted children, that was Owen. He wanted three—we compromised on one, as it was me who was putting in the heavy lifting. I hemorrhaged during Leif’s birth and nearly died. The first time I saw my son he had already been in the world for two days. Two days of bonding with everyone else except me. Two days of touching other hands, seeing other faces. I sometimes wonder if I’d had that first contact with him, would we have the bond that we should? Like those women who pull their own babies from their bodies, and in all their wetness and dripping fluid, hold them to their bare chests crying and laughing, forgetting all the pain and labor, letting the umbilical cord transfer all the needed nutrients, latching their babies to their breasts and feeding them what nature intended—colostrum. Colostrum, which I had to pump out and dump down the drain. I felt like a fake, the shocking scar across my belly to prove it. I no longer wore bikinis or exercised in only sports bras. Motherhood had taken that from me—had taken my body.

I was tying Leif’s shoelaces for school in the morning after another night of trying to soothe him back to sleep—it was my turn last night—when he told me of his other past life as a deer.

“I felt a hurt here,” he pointed to his chest, “in front of my two babies. I tried to run away from it, but the pain made me fall down and then everything went black and now I’m Leif.”

It was odd to hear him embody a deer and describe feeling a gunshot. I was sure we never told him anything about hunting and killing animals. I assumed he’d picked it up from some D-bag kid at school whose father goes out every weekend to destroy nature and bathe in the blood of his victims.

“Leif, we don’t talk about killing.”

I knew kids could have big imaginations, but up until this point, he’d been a pretty dull kid. No imaginary friends, no pretending he was a unicorn or anything.

Leif announced at dinner that he was not going to eat meat anymore by screaming the moment I put a piece of chicken to my lips.

“We don’t eat animals. We are animals,” he yelled and started crying over his cut-up chicken.

“Buddy, you’ve always eaten meat,” I said.

“I didn’t know what meat was. Marshall told me it’s dead animals.”

I always hated that little punk.

“You don’t have to eat it if you don’t want to,” Owen said, taking the pieces of chicken from Leif’s plate. I gave him a look, which he understood, and he gave me a look back. Parenting is just a bunch of looks sometimes. I didn’t think we should be the parents that let our kid run all over us—he didn’t think we should run all over our kid.

“We have to give him a proper burial,” Leif said.

“Of course, bud. We can do that.” God love him, Owen gathered the chicken from our plates and picked up the carcass. “What should we do?”

“Backyard.” We proceeded to the yard, Owen carrying the sacrifice. I wasn’t about to waste a whole rotisserie chicken on the raccoons. I sped up to Owen.

“I’ll distract him and you go hide it in the refrigerator,” I whispered.

“No way, he’d know.” He’s such a good dad, damn him. So, Owen dug a hole while Leif picked flowers from the garden and arranged them around the dissected chicken carcass. Once they were covered over, Leif began muttering in Sanskrit while spreading flower petals on the grave. He took his hands to prayer position at his heart, brought them to the middle of his forehead, and bowed.

“Namaste,” he said. Owen and I looked at each other. “We can go inside now.” He turned and ran inside, putting on the TV, dirty knees and running nose, and monk voice. Owen and I stayed outside.

“Vegetarianism, Owen? Why encourage that?”

“Why not? I think it’s cool that he’s socially conscious at such a young age.”

“But we can agree that he needs to see someone at least, right? I mean, a Buddhist monk, a deer?” He looked at his feet, pushing a stick with his shoe.

“When I get to the office in the morning, I’ll ask Rodney who his daughter sees.”

“I think it would be beneficial if you all went vegetarian with him, you know, show him that you’re supportive. He’s a serious little guy.” We were sitting in the therapist’s office after Leif’s first session.

“But what about the reincarnation monk stuff, and the deer—that’s unsettling right?” I said. Owen nudged my shoulder. The therapist gave an annoyingly cryptic therapist smile that probably meant she thought we were bad parents.

“Children often develop vast imaginations and stories as part of a coping mechanism when things change or they feel that they need something to make them secure.”

“You’re saying he doesn’t feel safe with us?” I said. Owen put his head in his hands. I didn’t get it apparently—I never do.

“Not really, but in a way. It could be something that happened at school. The big thing that you all need to show him is your support—he needs to know that you are there for him and he can talk to you if he needs to.” She paused. “Show an interest in the things he has started focusing on, like the monk and the deer. You may find it a bonding experience.”

So, I started asking him questions about his monk and deer selves. The therapist said we should encourage this, as it is a natural part of his development. I decided to leave work early and pick him up from school to take him for ice cream. Usually it was Owen who did these things, but I was determined to make a connection with him.

His mouth was full of chocolate ice cream; it ran down his chin and dripped onto his polo shirt, but I didn’t say anything about it. I just let him eat. The shop was local, organic, and had vegan options in case he wanted them. It was nice out, the rain had finally stopped, so we sat outside at the black iron table and watched the people walking and riding by with dogs and babies.

“So, what did you like most about being a monk and a deer?” I looked up from my bowl of untouched vanilla. He thought for a moment then put his spoon down and clasped his sticky hands together.

“I liked to ring the gong and see the mountains. The gong made me feel like my body was full of bees. Being a deer was more fun because I got to do anything I wanted. I miss it.” He resumed eating his ice cream and kicking his legs back and forth. I became curious.

“Do you wish you were still a deer?”

“Yeah, guess so.” He shrugged, then scratched his nose.

After this, he only really talked about being a deer; he spoke of dewy mornings in the hills and forests, of fog and sunlight and the darkest nights; he spoke of fear, but also the contentment of simply existing on earth, of leaping over tall fences meant to keep him out.

I started researching reincarnation, specifically stories about children who talked about their past lives. I was surprised to find that there were a growing number of accounts. Some people believed them, some didn’t—same story as with everything. I was shocked, however, by the accuracy of some of these accounts. Children describing the intricate details of their life as a Samurai without having previous knowledge of such things. Many of these accounts were posted on personal blogs. Some entire blogs were even dedicated to their children’s stories of their past lives. On Naomi the Elephant Girl, a blog by someone named Adriana L., I asked what she did when her girl started telling her about her past life.

She answered immediately: “We started asking a lot of questions, and above all, we didn’t treat it like a joke. Now I can 100% say that my wife and I believe her.” Reincarnation was not something I had spent much time thinking about before Leif’s stories. For whatever reason, I latched on to it.

A year after Leif was born, I was diagnosed with postpartum depression. My work at my consulting firm took such a hit that I had to step down from my executive role to focus on my recovery. I suppose I always blamed Leif for that—it wouldn’t have happened to a man—in fact, it didn’t happen to Owen; he didn’t have to give up his work in real estate. No, it happened to me. I was angry as I watched my male coworkers with children advance beyond me. At home with Leif, I stared at him for hours and wished he would disappear. Spending money on daycare felt ridiculous, since I was technically able to care for him, but I wished my life could go back to how it was before.

I fought to get back to where I was in my job, but there was something missing in me. Sometimes when I looked at Leif, I got a sense that I could see in him the thing that had gone missing in me. I wanted it back so much sometimes that I had the urge to claw it out of him, but I wouldn’t know where to look. But perhaps deep down I feared that part of myself was not meant to be found in this lifetime.

I got a call from the school saying Leif had pooped on the playground. I asked them if it looked “deerish.”

“Define ‘deerish,’” they said. I quickly looked up photos of deer poop on my phone.

“You know, like pellets,” I said.

“I’ll ask Diane; she saw it.” A pause. “Diane says, yes, it was deerish poop.” I told them he had digestion issues, which they didn’t seem to care about. They told me to come down right away and get him. Apparently, they drew the line at feces. “And actually, we need to talk about some other incidents that have been happening.”

I sat in the waiting room of the principal’s office and felt that familiar pit of dread in my stomach, as if I were a child, about to be punished for mouthing off to the teacher, again. I was a little punk, I won’t lie. Up until now, I thought Leif was the opposite of me—docile.

The concentrated smell of crayons overwhelmed my senses. The students’ artwork hung along the walls, not an inch of blank space left without a shitty giraffe with three legs, or a dog that just looked like a blob with a rogue eye coming out of one ear. Kids don’t get anatomy; none of these creatures would even be able to walk if they were real. I didn’t get the appeal and decided that kids are pretty bad artists for the most part. A smiling man poked his head out from behind the desk and told me I could go in to see the principal.

“We have a bit of a problem, Ms. Evans.” The principal looked concerned as I sat down in front of her desk. Her office was crowded, stacks of papers and boxes. She wore a pantsuit, but she had dark circles under her eyes.

“And what’s that?”

“Leif has been involved in multiple incidents, and we didn’t think it was serious until today when he used the playground as, well, a toilet.”

“Can I have specifics, please?” In response, the principal took out a file.

“He seems to have no regard for proper social and school rules. For instance, two weeks ago he started eating a classmate’s worksheet in class. A day after that, he was collecting and eating acorns on the playground, where he got other children to do the same. One classmate actually got sick.” She flipped the page, sighing. “Last week he was telling the teacher he didn’t have to listen to her; then just about every day, I’m told he scratches himself very disruptively and says he has fleas. The teachers tell me he even uses the table and other students as scratching posts, and now this.”

I wasn’t angry, just intrigued. When he got into the car, he looked out the window the whole way home and I wondered what he was thinking.

Back at home, he wanted to go out to the backyard. Our yard is forested, the type of yard I wished I’d had as a kid growing up. It’s unfenced, and the back portion is wild and overgrown and leads into the woods. There was an autumn chill in the air, and spiderwebs were popping up on every corner between every walkway, so that we had to bat them away or stoop under to avoid them. My father told me years ago that you know fall is coming when you start seeing spiderwebs everywhere.

I got a jacket and joined Leif in the backyard. He went straight for the forested section, and I saw him put something into his mouth. Getting closer I saw he was eating acorns and the leafy parts of some plants. I followed him and let him do his thing. Maybe I was a bad mother for letting him eat acorns, but it looked like he knew what he was doing, and there were some plants he avoided entirely. I just wanted to understand him.

“How do you know which ones to eat and which ones not to?”

“My deer mother taught me when I was a baby.”

I started to wonder about what my past life would have been. “Leif, who do you think I used to be?” At this, he left his foraging with a fist full of green acorns and leaves and walked over to where I was kneeling in the grass and pine needles. He put his free hand on my face and looked into my eyes.

“I think you were someone really sad and lonely, and it was so big that it followed you here.” Jesus, maybe he had been a monk. He stood there, and I put my arms around him and hugged him to my body—needing to feel something living close to me. He rested there only a few seconds before squirming out of my grip and running off into the trees.

No one told me about postpartum depression. I didn’t have anyone to reassure me that I was not broken. I still felt as though I had no one to tell me these things. There was part of me that believed I would never find my missing pieces—that they had been scattered across the globe and nothing short of a Tolkien-like journey could bring them back to me. I was rebuilding, but from what? I had tried all the medications. Nothing helped.

And then there was the part of me that Leif had cracked open, the part that believed I had always been doomed. I felt like something I had done in a past life had karmically cursed me in my subsequent lives. I was at the point where I’d believe anything.

Owen called and said he was driving home. I told him Leif had pooped on the playground and was currently eating acorns.

“You don’t seem mad.”

“Not mad, more curious than anything.”

“Hang in there, we’ll get through to him. Love you.”

“Love you. Hey, Owen—do you think I’m a sad person?”

“Rachel.” He paused. “We’ve always known you weren’t the happy peppy type.”

"Stag," from Under My Skin by Luis Lazo. Courtesy the artist

I swear, when I woke Leif up for breakfast, there was a different essence about his face, a primitiveness that wasn’t there when I put him to bed. I couldn’t explain it.

“Do you have friends at school?” I asked him while he played with blocks in the living room.

“Not really, I just play by myself.” He knocked down the tower he’d built and started cleaning up the rubble.

“Are the other kids mean to you?”

“Sometimes they call me weird. My teacher thinks I’m weird too.”

“Well, I like your type of weird, buddy.” I smiled and ran my hand through his fine hair.

Later, I picked up a picture book about deer at the store. That night after I had given him a bath, Owen and I lay in his bed and read the book to him. It was rare that we did this, lying there as a family. It was rare that I felt good doing this; I felt more like a mother with my son lying against me and reading about the different types of deer and my husband behind us, me leaning against his weight, him encircling us with his bigness. We were a family. Leif laughed at every page. I’d never seen him so engaged with a book before.

“Oh, Mom, look at that. One day, I’ll have points like him.” He pointed to the antlers on the buck on the next page. Owen laughed.

“I wonder if antlers can do this.” As he reached over and tickled Leif’s sides, Leif screamed, put his arms around me, and squeezed tight.

“Save me, Mom!” he yelled. I hugged him back, protecting his body and laying kisses on his head, soaking up the feeling of being a mother.

I smiled at Owen and wished I could relive this moment in all my future lives. I wished that in all my lives there would be love like this—that my son and I would meet as different people in different bodies at different times, and each time we’d learn to love each other better; each time we’d realize our cosmic connection sooner. I hoped that we would recognize each other and that those moments would transcend lifetimes and starve away the sadness within me.

It was midnight when we were awakened by the downstairs door sensor beeping. Owen and I went downstairs to find the back door wide open and Leif asleep in a heap on the ground wrapped in his blanket. Owen picked him up and carried him back into the house, but Leif woke and started crying, begging to go outside. We stayed with him and read the deer book until he finally fell asleep again. We were all on the couch; Owen and Leif slept, but I was wide awake with Leif stretched across my chest. I moved my hand in circles on his small back, the weight and heat of his body soothing me. The birds had yet to start chirping, and in the quiet of our living room, as I held my son, it occurred to me that maybe we were part of each other, and maybe my missing pieces were not missing after all.

In my research on reincarnation and karma, I learned that the Buddhist life cycle is called Samsara. Life, Death, and Rebirth all connect to the karma you produce from each life. If you live a good life, your karma is good, bad and your karma is bad. Your karma determines what or who you will be reborn as. I thought about my life; my karma was surely bad until this point. Not murderer bad, but I definitely wasn’t Mother Teresa. Karma reminded me of the Catholic teachings I grew up with: Do good so that you will get something good in return. I just didn’t see the purity in doing good just to get into heaven. On the opposite side, maybe humans are so messed up that they need threats to be good people.

I wondered if it was too late to change my karma. Was it already my fate to be miserable in my next life? The thought made me want to give up. I was so tired of being miserable. Was it bad karma to be sad about nothing in particular—to be sad about having too much and feeling like it was all nothing, useless—that I was useless? Could depression get me reborn into a toad? No, that wasn’t it—but I wanted to believe that depression made my life more sacred. To be latched to a burden—to struggle just to live—was my own good deed to the world, to take this weight and bear it myself—to fight to see the light that others didn’t notice. Perhaps this awareness of the dark was what purified me. I lived in the dark so others could thrive in the light.

His ears started changing. They looked bigger than before, ever so slightly curved. His nose was noticeably wider. He seemed happier than he had in a while and spent the entire day outside. When I called for him to come in for his dinner, completely vegetarian now, he came running up.

“Can I sleep outside?” he said.

“No. We sleep in beds.”

“There are beds outside. I like outside. I feel better there. I used to sleep outside. Why can’t I now?”

“Well, now you don’t sleep outside—you have a bed inside.”

He started growing a thin, fawn-colored fuzz on his body. I dressed him in a beanie, long sleeves and long pants. He didn’t want to go to school, but I told him if he was brave, we could go camping over the weekend and he could sleep outside.

I was in a meeting with my new clients when my assistant rang in to say that the school couldn’t find Leif. Even last month I would have been mad at him for messing up my meeting, but I wasn’t mad this time—I was only worried about him. I handed the meeting over to my coworker and rushed to the school to find the police and Owen already there. Apparently after morning recess, he didn’t come back in with the other students. They thought he’d slipped through a gap in the fence.

“I’m so sorry,” said the principal. “The recess teacher on duty had to break up a biting fight, and we think that’s when he ran away. We checked the whole building.”

The officer cleared his throat. “Most likely he tried to run home, or he’s nearby the school. We’ll have a couple officers looking here and I suggest we go look around your neighborhood and all possible routes to your house.”

He glanced at Owen and me. “We really need to find him before the sun goes down and the temperature drops.”

We looked all afternoon, circling around our neighborhood, calling for him, driving all the routes we took to school. It started to get dark, and I could feel the cold in my lungs, the crisp air like a death sentence. Owen began to break down, and I wanted to as well. We were sitting on the back of the fire truck drinking coffee in Styrofoam cups.

“What if…” he started to say, tears in the corners of his eyes.

“Don’t even think that. We’ll find him.”

It was midnight when we went back to our house, hoping that this time, he would run around the corner into our arms. We couldn’t sleep. The police were searching the city and our neighborhood, and they had posted an officer out front overnight and put out a missing child alert. We’d called everyone we knew to help look, and they were out scouring the neighborhood. I felt like it was wrong of me to take a break, to sit down when my child was still out there. I put on my winter hat, gloves, a warm jacket.

“Where are you going to look?”

“Out back again; he’s been obsessed lately.”

“I’m coming too.” We called his name, tramped through the overgrown brush, the thorny vines capturing our feet, leaves crunching beneath us. We could see our breath in the beams of our flashlights. It was another hour before we found him huddled under the bushes and brambles in the woods behind our house. He’d wedged himself so deep in the branches, we could barely make out the reflective dinosaur jacket I’d put on him that morning. Owen gently pulled him out from under the bushes. He was breathing—warm even—gangly body, spindly legs, and too-big ears. He was fast asleep, looking like he was sleeping better than he had in months.

As Owen laid out the cushions from the patio furniture in the grass and took some blankets from the couch, I made sure the police and everyone else knew that we’d found him. We settled down on the makeshift bed and put Leif between us. Owen took my hand across our son’s small body, and our gaze met over the rise and fall of his fawn-spotted coat. Leif turned and nuzzled close to me. I rested my head on his, breathing in his soft wild smell. I held my family in my arms, knowing I was not strong enough to keep them, and closed my eyes to all the noises of the animals at night.