Her Rightful Place

The everlasting legend of Tanya Tucker

By Jason Kyle Howard

Photograph © Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

On a cool night in downtown Los Angeles in January 2020, barely six weeks before the world closed down, Tanya Tucker stood on an island stage at the Grammys in the middle of the cavernous Staples Center, alone except for Brandi Carlile, who was hunkered behind a Roland baby grand piano. For a moment there was silence, even stillness, and then the audience began to applaud and yell. As Carlile struck the first chords of “Bring My Flowers Now”—a song she co-wrote with Tucker and Carlile’s bandmates Phil and Tim Hanseroth—television cameras captured Tucker in a candid moment of vulnerability she rarely displays.

The then-sixty-one-year-old veteran performer took a deep breath. The beading of her suit, along with her platinum hair, streaked bubblegum pink, glowed in the spotlight. She reached for the drape of her exquisitely tailored jacket, stroking it for reassurance, or perhaps to ground herself in the moment she must have thought would never come. Then the muscle memory of nearly fifty years in the business—five decades of playing barrooms, casinos, rodeos, state fairs, arenas, even the Super Bowl; five decades of peaks and valleys, of being lauded as an innovator and dismissed as a has-been—took over. She straightened her posture and began to sing.

The very sight of Tucker at the Grammys, much less standing center stage in primetime, was an unlikely one, and not just because she had been in semi-retirement from recording for over ten years before the release of While I’m Livin’ to universal critical acclaim in 2019. Backstage at the awards show in 1992, Tucker pulled what might have been her Biggest Badass Moment in a career that boasts a legion of strong contenders for the honor. Across the nation, country music’s popularity was exploding. People who had previously derided the genre as tired and hokey were now embracing the genre-blurring sounds of Wynonna Judd, the acrobatic showmanship of Garth Brooks, the sophisticated balladry of Trisha Yearwood, and the fiery sex appeal of Tucker. But the Grammys, at least in Tucker’s estimation, had not caught up. To her, this was evident in the number of country awards being given earlier in the afternoon (away from the main stage and the attention of the world’s media), and in the way she and other country performers were treated backstage, relegated to sharing dressing rooms with backup singers for pop acts. After presenting three country awards onstage with Chet Atkins, Tucker made her way as instructed to the press room when something came over her. She felt a need to defend the honor and integrity of her native genre.

“I’m gonna tell you people something,” she announced. “Country music is the greatest music in the world, and I’m proud to be a part of it. We come to these Grammy Awards and you all act like rock and roll is the only music in America. We come here as representatives of our music, and we get treated like redheaded stepchildren. I for one am getting pretty damn tired of it, and you can stick your awards up your butt.”

But that wasn’t all. In a moment captured by a People magazine photographer, Tucker turned to leave and, moved by the moment, flung a chilly look over her shoulder, calling attention to the plunging cut-out of her gown that revealed her creamy bare skin. “See this back? That’s the last you’re gonna see of me.” And with that she turned on her stilettos and flounced from the room.

Nearly thirty years later, Tucker had set aside her rancor and stood at center stage, looking for a new beginning with the industry. Earlier that afternoon, in presentations still not deemed high profile enough for the primetime telecast—a move that must have rankled her still—she had taken home two Grammys out of four nominations. At the podium expressing her gratitude for being awarded Best Country Song for “Bring My Flowers Now,” she turned nostalgic. “You know, after almost fifty years in this business, after many dreams, it’s still unbelievable to me that I’d still have a few firsts left. So after fourteen trips, fourteen nominations, this is the first win and”—interrupted by applause, which was led by Brandi Carlile standing beside her, Tucker became emotional and seemed at a loss for words—“I can’t believe it…And I just want to say, no matter how young or how old you are, never stop following your dreams. Keep going.”

But her triumph wasn’t over. Soon, she was called back to the stage to accept the award for Best Country Album. This time Carlile, who produced While I’m Livin’ alongside Shooter Jennings, spoke: “Me and Shooter asked Tanya why she hasn’t made an album in almost twenty years, and she said it’s because when her mom and her dad died, she just couldn’t do it anymore, and she thought that it meant there was more love behind her in her life than ahead of her. And she knows that’s not true right now.”

That must have been what Tucker was feeling on that island stage: that somehow, all the years of struggle, grief, and loss had been worth it. Her rough-hewn voice—now huskier, wiser, leathered from cigarettes, drink, and living—filled the arena with its emotional precision and honesty: Bring my flowers now while I’m livin’ / I won’t need your love when I’m gone. Between the lines of those poignant lyrics, there is an unmistakable message.

This is what you’ve been missing. There are stories in this voice. Listen.

Before anything else—before the drug use, the provocative outfits, the stint at Betty Ford, the tabloid focus on her romances and offstage antics—there was the voice and the stories it told. Always sounding older than her years, capable even at thirteen of accessing reservoirs of emotion and knowledge that rightfully belonged to a woman twice her age, Tucker instinctually knew how to use her voice to tell a story.

While every song tells a story to some degree, not all songs are “story songs.” These function as musical short stories or even novellas, compact narratives filled with characters, plot, sense of place, and drama. Think Bobbie Gentry’s classic “Ode to Billie Joe,” one of the greatest American songs ever written, and its evocative beginning: It was the third of June / another sleepy, dusty Delta day. When married with the song’s languid shuffle of guitar and moody strings, that becomes the stuff of great musical narrative.

Now primarily the territory of the Americana genre, such story songs were once the lifeblood of mainstream country, and Tucker is one of the form’s finest interpreters. She cut her musical teeth on them. If you mine the narrative terrain of her first three albums, which she recorded between the ages of thirteen and fifteen, you’ll find a landscape populated with them. The legendary Billy Sherrill, her first producer, knew what he had on his hands: a prodigy who could wrap her voice around a lyric, who knew how to sing of grief and longing, of danger and revenge.

In “The Jamestown Ferry” (number five on the Billboard country charts in 1973), included on her debut album, she inhabits the character of a woman abandoned by her man. “What’s Your Mama’s Name” (number one in 1973), the title track on her second album, tells the story of Buford Wilson, who is searching for a woman he once knew in New Orleans who has given birth to a “little green-eyed girl.” The chilling “Blood Red and Goin’ Down” (number one in 1973) sees Tucker as the young girl riding through rural Georgia with her daddy as he looks for his cheating wife and, after an act of violence, sees her mother and her mother’s lover “soakin’ up the sawdust on the floor.” In “The Man That Turned My Mama On” (number four in 1974), she becomes another young girl, this one curious about her absent father. “No Man’s Land,” which was never released as a single, is perhaps the darkest tale of all. Tucker transforms into Molly Marlo, a young rape survivor who later gets revenge on her attacker while serving as a prison nurse. (It’s at once incredible and disturbing that she recorded this song when she was only fourteen.)

Even as Tucker got older, moving from adolescent hitmaker to a sophisticated twenty-and-thirty-something with a remarkable run of successful chart singles beginning in the late Eighties and continuing through the mid-Nineties, she remained faithful to the form of the story song, recording them with more contemporary, and often uptown, twists. The scorching “I’ll Come Back as Another Woman” (number two in 1987) endures as one of country’s greatest kiss-offs, with a wronged woman vowing to seek her revenge in reincarnated form. “Two Sparrows in a Hurricane” (number two in 1992), a tender ballad that endures as one of Tucker’s signature songs, chronicles different eras of a romantic relationship, with artifacts—such as a set of car keys—that recur in moving ways, the last instance in old age.

And then there’s “Delta Dawn,” the most famous song in her extensive catalogue, which marked its fiftieth anniversary in 2022. Written by Alex Harvey and Larry Collins, it depicts a faded forty-one-year-old beauty who, haunted by the man she lost years before, roams the town of Brownsville, Tennessee, in expectant, futile pursuit of him. The fact that Tucker even recorded it is a bit of a miracle.

The story goes that one night, her producer Sherrill tuned in to The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson and saw a then-unknown Bette Midler perform the song. Sherrill was so taken with Midler and “Delta Dawn” that he tried to sign her, but upon learning she had already secured a record deal, he took the song to Tucker. It became her debut single, rocketing to the top ten of the country charts when it was released in April 1972 and establishing the thirteen-year-old singer as a star.

Although Midler recorded “Delta Dawn” first, and although Helen Reddy took it to the top of the pop charts in 1973, it is Tucker’s version that has stood the test of time. There’s a reason why, on Spotify, Tucker’s “Delta Dawn” has notched nearly 40 million streams, compared to 6.5 million for Reddy and, as of this writing, 439,000 for Midler. A saccharine facsimile of Tucker’s down to its distinctive a capella opening, Reddy’s cloying delivery simply lacks authenticity. Midler’s is far better; in her hands “Delta Dawn” becomes a different song altogether. She infuses her vocals with a gentle loneliness, following the music’s build from a quiet opening to a torch finale, replete with r&b flourishes.

But even The Divine Miss M can’t approach Tucker’s performance, which is rendered with a toughness and vulnerability that haunts the listener. There’s something about the a capella opening of the chorus—how her young but implausibly careworn voice soars over the resonant backing vocals of the Jordanaires, who function throughout the song almost as Brownsville townsfolk bearing witness to Delta Dawn’s heartache. The way Tucker renders the word dawn—pronouncing it with a long o, doan, and dipping the first syllable down one note before returning the second to its proper place—roots it in a distinctly Southern and rural setting. When she unleashes her vibrato, which sounds like a bucking bronco she is just learning to tame, Tucker lends the title character’s search an urgency. She makes it clear that Delta Dawn’s hunger is not just emotional; it’s also carnal. The effect is a sung short story that is immediate, innate, inhabited—qualities a producer might recognize and encourage but could never teach, not really.

When she sang “Delta Dawn” as her encore in January 2020 during a two-day sold-out residency at the Ryman, Tucker held the capacity crowd in the palm of her hand. As she belted the lyrics, strutting the stage in an all-black ensemble—a lace top and form-fitting trousers, an enormous bejeweled belt, and fringed boots—the audience sang along. Some had tears in their eyes from Tucker’s emotional delivery. Along with my husband, I was sitting with two remarkable Americana singer-songwriters, Hayes Carll and Allison Moorer. A lauded vocalist and Academy Award nominee who has given and witnessed hundreds of remarkable performances, Moorer grabbed my hand at one point and mouthed Wow. Somehow, despite singing “Delta Dawn” thousands of times across five decades, Tucker was able to still fully embody the lyrics and convey the rich emotion of the character.

Perhaps that’s because in addition to her innate talents as an interpreter, Tucker is also a student. You can hear shades of Connie Smith in her voice—in her phrasing and inflections, such as the way she sometimes punctuates the end of a line with the hint of a sob. Loretta Lynn, whom Tucker counted as a close friend up until her death in October, is there too, her homespun moxie felt in Tucker’s unapologetic bravado. But above all there is Elvis Presley, whom Tucker has long idolized and to whom she has often been compared in her sensuous live performances. In her memoir Nickel Dreams: My Life, Tucker recounts how Presley once gave her a lesson in stage presence. Back in the mid-Seventies, Tucker and her sister attended one of his concerts in Las Vegas. Presley got word the young country ingenue was in the audience and, in the middle of the show, he descended from the stage. Tucker writes that Presley “leaned over me, sexy as all get out, swinging his body around and smiling at me, ‘This is how you do it, girl.’ I knew he was right, too. He had the moves and I wanted to have them, too.”

Apparently, she already did. When Tucker played Denver, Presley returned the favor and slipped into the wings of a club to watch her perform. Before he left, he turned to Mae Axton, the legendary songwriter who had co-written “Heartbreak Hotel” and who was also a friend of Tucker’s, and observed, “She’s a female Elvis Presley.” Even today, at sixty-four, there are few performers in any genre who can match the electricity and sensuality Tucker brings to the stage. Her entire body becomes part of her interpretation of a song, swaying and strutting and moving her hips, submitting to the demands of the song’s mood and rhythm.

Despite all of this—her undeniable gifts as an entertainer, as a vocalist, as a musical actress even—somewhere along the way the industry’s, and even sometimes the public’s, awareness of her substantial talents got lost. And it took a respite from the pressures of the business, and the demands she placed on herself, to bring it back into focus.

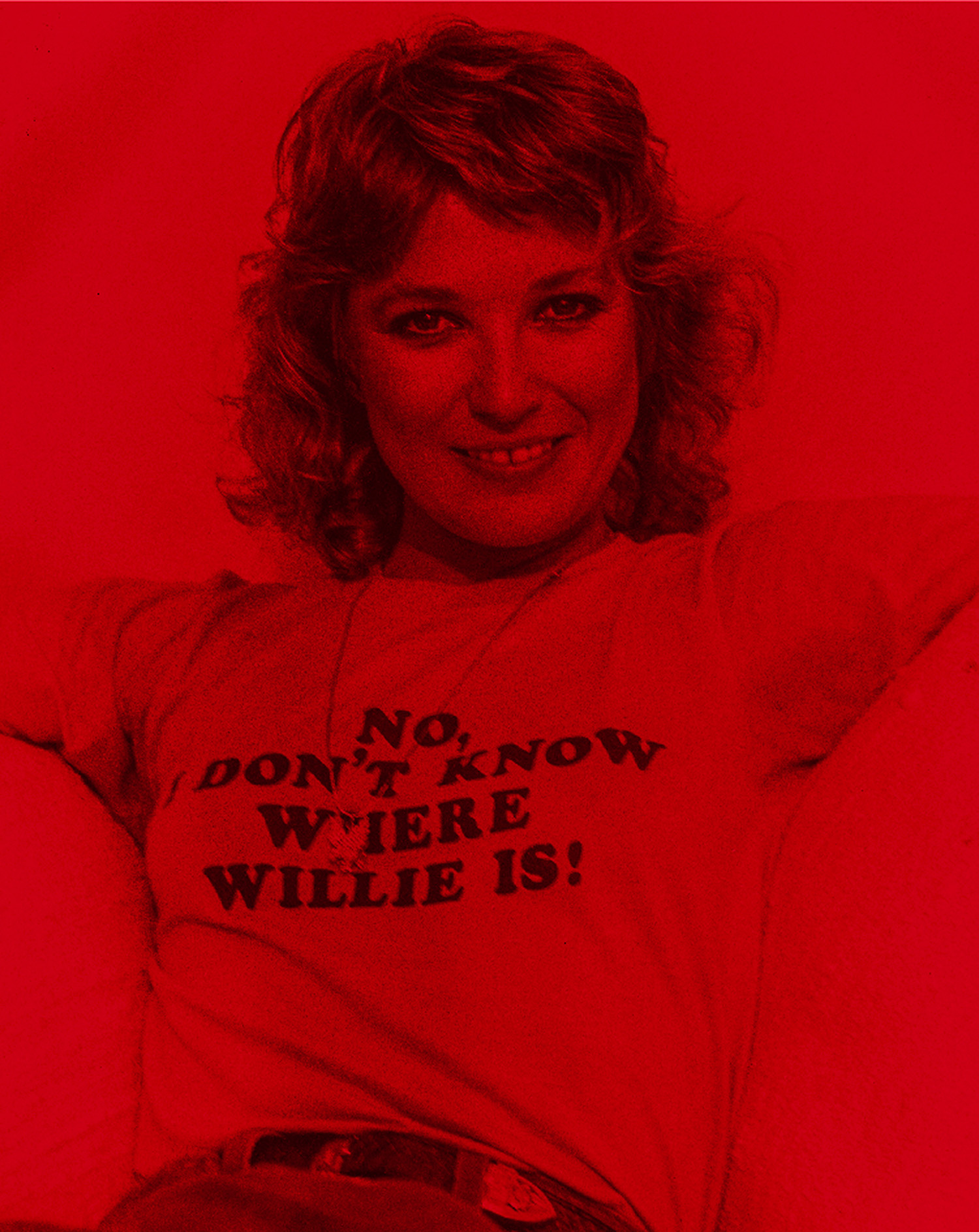

Photograph © Globe Photos/ZUMA Wire/Alamy

Ever since she was a teenager, Tucker has always lived her life on her own terms. When she was fourteen, she recorded David Allan Coe’s erotic ballad “Would You Lay With Me (In a Field of Stone)” over her parents’ objections—and took it to the top of the country charts and number forty-six on the Billboard Hot 100. Even then, she knew her own mind.

By the time she was coming of age in the late Seventies, Tucker was itching to venture into new artistic territory. She had changed management, moving from Nashville to L.A., and her new representatives were encouraging her to try her hand at rock. The result was TNT, an album better remembered now for the provocative poses Tucker struck in the album’s artwork. No longer the demure adolescent decked out from neck to ankles in gingham, on the cover she sports skintight black leather pants and a flirty button-up. Her lips are parted in a come-hither look with a microphone held near her mouth, its cord snaked between her legs. On the interior sleeve, the camera captures her looking over her shoulder, a crimson spandex suit hugging her body as she clutches a bundle of dynamite.

While TNT didn’t exactly create an explosion on the charts, it did signal a new period in Tucker’s creative and personal lives. To many country fans, she had gone Hollywood in both music and image. She was also living in the fast lane for the first time, drinking and experimenting with drugs. Then she fell into a relationship with Glen Campbell, the Rhinestone Cowboy and member of the fabled Wrecking Crew, the group of studio musicians who played on everything from Frank Sinatra’s “Strangers in the Night” to the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds.

Tucker was twenty-two, Campbell was forty-four, and that marked age difference, coupled with rumors of rampant cocaine use and physical violence, created a tabloid firestorm. Although the intense relationship lasted just over two years, Tucker has long maintained there was real love there—and that she and Campbell could have made it had it not been for the drugs. When he died from Alzheimer’s-related complications in 2017, she mourned him deeply, releasing a tribute song in his honor.

In the wake of their tumultuous breakup, Tucker increasingly turned to partying and garnered more headlines in the tabloids for her love life—both real and imagined. There were rumors of a reunion with Campbell that turned out to be false, although Tucker later admitted in Nickel Dreams she would have been willing to take him back. When she ran into Clint Eastwood, an old acquaintance, at a bar in Aspen and was pictured with him the next day on the ski slopes, the National Enquirer cooked up a romance. “By the time it made the papers, I’d broken up Clint’s long-term love affair with Sondra Locke,” she wrote in her memoir. But one thing was true: “I was wearing down. I looked older than my years, and I was exhausted a lot of the time.” Her fans began expressing concerns, including one elderly woman she remembered who approached her after a show in Fort Worth. “‘You gotta start takin’ care of yourself, child,’ she said. Nobody knew that better than me, but I wasn’t taking the good advice.”

Worried for her health, Tucker’s father stepped in and moved her back east to Nashville in the mid-Eighties. The industry didn’t roll out the red carpet; they considered her washed up. She wasn’t even thirty. But she, along with her father and her producer Jerry Crutchfield, managed to resurrect her stalled career with Girls Like Me, an album that produced a number-one country hit with “Just Another Love” and three other Top Ten singles when it was released in 1986. Still, her family staged an intervention, and Tucker spent twelve weeks at the Betty Ford Center.

In her memoir, Tucker explains that she went unwillingly, only to please her parents. While the stint in rehab slowed her down, it did not completely tame her; she continued to enjoy the occasional drink. But it did give her a clearer perspective, which paved the way for a meaningful romantic relationship with burgeoning actor Ben Reed, with whom she had two children: a daughter named Presley in 1989, and two years later, a son, Beau Grayson. (Another daughter, Layla, with Nashville musician Jerry Laseter, would follow in 1999.) While her romantic relationship with Reed did not last, the two maintained a friendship and co-parented their children. And in yet another Badass Moment, Tucker called out Vice President Dan Quayle in the wake of his 1992 attack on single mothers via Murphy Brown, the television character played by Candice Bergen. Quayle’s comment set off a national firestorm, and just like she had done at the Grammys earlier that year, Tucker felt compelled to respond.

“Who is Dan Quayle to go after single mothers?” she asked the New York Daily News. “What in the world does he know of what it’s like to go through pregnancy and have a child with no father for the baby? The real trouble with these situations isn’t the women having children out of wedlock, it’s men with no backbone like Dan Quayle who don’t understand their plight.”

During this period, the continued salacious stories in the tabloids of Tucker’s colorful personal life sometimes subsumed her music. Did these depictions match reality? In some cases they did, as she has readily admitted in interviews and in her candid memoir. Similar behavior by the likes of Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Hank Williams Jr., and George Jones enhanced their status as outlaws, earning them the status of anti-heroes to be venerated and emulated. But while Tucker’s press coverage might have increased her fame—“This bad reputation has made me a damn good livin’,” she jokes in a new documentary—much of it was rooted in misogyny, such as when People magazine observed in 1988 that Tucker “has had more boyfriends than some people have had hot meals.” As was the case with other female artists who refused to toe the conventional, proper, patriarchal line, the breathless stories about her were often inflated and conflated to create a caricature that overshadowed an astonishing artistry.

During Nashville’s annual awards seasons, she was often overlooked. Despite five nominations as Top Female Vocalist from the Academy of Country Music, Tucker never won the award. She fared slightly better with the Country Music Association, which had nominated her six times before she finally won their Female Vocalist of the Year award in 1991. (“Thank God,” her celebrated contemporary and fellow nominee Reba McEntire was quoted in Nickel Dreams as saying. “Thank God she finally won that award.”)

And yet the quality of her singles from this period remains incontrovertible. Listening to “Love Me Like You Used To,” her number-two single from 1987, offers a master class in vocal restraint. Tucker’s plaintive vocals, delivering lines that cut to the emotional quick—we used to play around under the covers / but now it’s just a place to watch TV—capture a yearning that is at once emotional and sexual. The dark, bluesy groove of “Some Kind of Trouble,” which appeared on her album What Do I Do With Me and peaked at number three in 1992, sizzles with Tucker’s trademark sass. As she sings about being behind on her rent, learning her boyfriend is cheating, and losing her job, you can hear the lived experience in her voice. Her playful vocals on “Down to My Last Teardrop,” when she puts her straying man on notice with the suggestive lyrics I don’t care who or what you’re doin’ / Ain’t gonna be no more boo-hoo-in’, capture Tucker at her feisty best.

Beyond their commercial performance, songs like these endowed Tucker with an identifiable quality. In a genre that prides itself on creating and maintaining a close, personal connection with its listeners, it’s little wonder that Tucker’s songs were so successful. She had been there too, her fans believed. Her songs appealed especially to women—particularly single women and newlyweds—and to rural gay men, who recognized in her all the characteristics of a good fag hag: acceptance, campiness, a shoulder to cry on, and a wild streak.

This knowledge must have sustained Tucker in the late Nineties, when her long period as a chart powerhouse began winding down after the release of Complicated in 1997. Only the single “Little Things” reached the Top Ten. Although she continued to tour, her recording output became sporadic. Following the release of Tanya in 2002, the highest single of which charted at number thirty-four, and the deaths of her beloved parents, Tucker fell into a depression and lost much of her creative drive. She spent a lot of time on the beach in California and on her ranch with her beloved horses. My Turn, her 2012 album of country covers she had long wanted to make, proved a creative disappointment. Tucker didn’t know if she would ever record again. She was mistaken.

In The Return of Tanya Tucker: Featuring Brandi Carlile, a documentary that premiered at South by Southwest in March 2022, director Kathlyn Horan skillfully and tenderly captures Tucker’s return to the studio to record While I’m Livin’, her first album of original material in seventeen years. The night before the recording sessions began in January 2019, Carlile realized they should be documented. She had been talking with Rick Rubin, who had expressed regret that he hadn’t filmed in the studio when he helmed Johnny Cash’s American Recordings, which kickstarted a creative and critical juggernaut in the singer’s last decade. Heeding his advice, Carlile got in touch with Horan, whom she had met through her wife Catherine Shepherd. As a fellow fan of Tucker’s, Horan responded with an emphatic Hell yes.

“The moment I first spoke to Brandi, I hoped there would be a film,” Horan says. “As we began to roll, it was obvious there was something extraordinary happening…By day two, I knew we needed to keep filming beyond the recording session and there was an opportunity to tell Tanya’s story in a new way.”

The Return of Tanya Tucker is compelling, captivating in its portrayal of Tucker as an artist who, despite all the gold and platinum records and the decades of experience, is plagued with insecurities. “I’ve come back so much they don’t believe it no more,” she says. What emerges from the film is the courage it must have taken Tucker to enter the studio with new producers who are a generation younger than her and to be vulnerable in front of them—and the cameras.

Horan explains, “She didn’t approach this with the protections and preciousness one might expect from such a legend. Tanya is generally a pretty open person, which is one of the reasons she’s so compelling to be around and I think why her fans are so devoted to her. Tanya has always presented as tough, so I think the level of vulnerability we see [in the film] has an even bigger impact…I think revealing the artistic process in such depth is something she hadn’t done. She is a total perfectionist and vocal master, so having that access was pretty incredible and [something] we didn’t take lightly. I don’t think Tanya thought about allowing this to happen at the time, I think she just trusted us.”

Tucker was initially hesitant to make While I’m Livin’. Although she had known producer Jennings most of his life via his famous parents, Waylon Jennings and Jessi Colter, she was unfamiliar with Brandi Carlile and her music. (“I didn’t know who the hell she was,” she confessed to Entertainment Weekly.) She was also not convinced about the songs. A creature of the old ways of Nashville, when artists and producers would scour a stack of demos they had been given and attend guitar pulls in living rooms and writers’ nights at the city’s bars in search of new material, Tucker has long prided herself on being able to pick hit songs. Her track record, after all, speaks for itself.

Tucker had recorded some of the biggest-selling country singles of the 1980s and 1990s. Over the course of her career, she has released ten number-one singles, a staggering forty Top Ten hits, and eight Top Twenty recordings on the Billboard country charts. The songs Carlile brought along were different; they hit especially close to the bone. Carlile, along with her bandmates and songwriting partners Tim and Phil Hanseroth, had studied Tucker’s life and career, and then set out to write songs that built a near-mythical narrative around her. Except for a few notable tracks like “Changes”—which Tucker co-wrote in the aftermath of her breakup with Glen Campbell and which stands as one of her finest, if largely forgotten, songs—she had typically steered clear of memoiristic material, preferring to immerse herself in character. This time, the character would be her.

While she considered these songs, evaluating their messages and quality, Tucker knew in her bones this would not be a commercial record that would blaze up the country charts. Were she to proceed, she would need to let go of her entrenched expectations and learn a new way to work.

“Mustang Ridge,” the album’s spirited opener, captures the pull of the road for Tucker—and her ambition to leave her native Texas behind in pursuit of her musical dreams. “The Wheels of Laredo,” an epic track that is one of the album’s highlights, captures vivid scenes from along the Mexican border that are infused with equal measure of beauty and longing. Tucker’s devotion to her beloved father is present throughout the album, but especially on “The Day My Heart Goes Still,” a ballad of unconditional, undying love. For good measure, she covers Miranda Lambert’s “The House That Built Me,” easily one of the finest mainstream country tracks of the century, and plumbs new depths of emotion with her gravelly vocal. While I’m Livin’, of course, wouldn’t be a Tanya Tucker album without a boot-kicking track, in this case “Hard Luck,” which could easily serve as a summation of Tucker’s artistic drive and stubborn will: Hard luck, keep truckin’ / I was born to a hard luck world.

As Carlile and Jennings coaxed her into the process, Tucker finally saw she had little to lose. The last twenty artistically fallow years had been a struggle. She knew she had more to say, more to give. Maybe she called up a memory: the spark of ambition she felt as a child back in St. George, Utah, one day when she and her father Beau were on the way to Los Angeles in search of a recording contract. The young Tucker had started to enjoy school and had momentarily placed it before her music. As they were leaving St. George, Beau Tucker pulled over and asked his daughter a question. “What’s it gonna be, Tanya? We can keep on trying or go home and you can have this regular life you’ve started to love so much.” Her reply was emphatic, if silent. She pointed in the direction of L.A., and her father began to drive.

That spark, Tucker decided, was still there. It just needed to be kindled—and Brandi Carlile was just the person. It helped that Carlile had been raised on Tucker’s music and knew her extensive catalogue inside and out. Although Tucker was unfamiliar with the younger artist, at their first meeting she recognized in Carlile a kindred spirit, someone she could trust, and she slowly began to let down her guard.

An acclaimed singer-songwriter with a cult following, Carlile had seen her own career explode to stratospheric heights after she sang her song “The Joke” on the Grammys in 2019, a performance so riveting that she went from playing small theaters to Madison Square Garden almost overnight. Like Tucker, Carlile is also a consummate student who enjoys paying homage at the feet of her elders, including Joni Mitchell, Elton John, and the Judds.

While she treated Tucker with the respect she deserved, Carlile was also determined to challenge her. When Tucker doubted the quality of her vocals—wishing she had held a note longer, or pushed her voice higher—Carlile reassured her, and even tenderly laid down the law, a moment that is captured in the documentary. This album was a portrait of Tanya the Vocalist, not Tanya the Entertainer. What mattered most were the layers of emotional authenticity that were naturally present in each take.

Carlile and the Hanseroth twins also managed to draw out a song from Tucker, one she had begun composing decades before but had never quite been able to finish. The Return of Tanya Tucker captures the moment when Tucker offhandedly sings the chorus, fully formed except for a word or two, and provokes an immediate, emphatic response from Carlile: “That belongs on this record.” The track, “Bring My Flowers Now,” becomes the album’s beating heart, telling the story of a woman who, after a lengthy career spent in the public eye—enduring dizzying heights of phenomenal success and periods of being undervalued and written off—is insisting on her due here, now, while she is still around to appreciate it. Don’t spend time, tears, or money / Over my ole breathless body, Tucker warns. If your heart is in them flowers, bring ’em on.

When it was released in August 2019, While I’m Livin’ received widespread acclaim, with the New Yorker opining that it “might be the best record of Tucker’s career; it is certainly one of the albums of the year.” While I’m Livin’ appeared on a slew of year-end lists, including those of Billboard, Variety, NPR, Stereogum, Paste, and No Depression, and topped Rolling Stone’s ranking of Best Country and Americana Albums. This reception, coupled with Tucker’s triumph at the Grammys, revitalized her career and introduced her to a new generation of admirers. Among music fans and industry insiders alike, there was a newfound respect for Tucker and her talents; the New Yorker heralded her as “one of America’s great vocalists.”

Although Tucker hadn’t changed, the times had. She had made the right album at the right time. Despite mainstream country’s continued domination by Bro-country acts, whose songs about beer and trucks are nearly indistinguishable, the growth and success of Americana over the past twenty years has opened up space for artists like Tucker. Instead of relegating them to “Legacy Artist” status, a pejorative death knell for those considered to be no longer commercially viable because of their age, Americana welcomes seasoned performers and songwriters with open arms. Album releases by the likes of Emmylou Harris, Rosanne Cash, and Lucinda Williams are treated as Events. The genre places a premium on honoring both tradition and artistic innovation, and its listeners and record executives alike have a finely tuned ear for rich narratives and characters.

What’s more, American culture itself had finally begun to change. After all these years, Tucker was finally being valued not in spite of being country’s Original Female Badass, but because of it. Her wild streak, for which she had previously been essentially slut-shamed in some quarters, was now seen as pioneering. She was embraced as a feminist icon who had owned her sexuality at least twenty years before Shania Twain scandalized Nashville in the mid-1990s by revealing her navel. She had survived a relationship fraught with domestic violence. She had given birth to three children while refusing to marry their fathers, and what’s more, she had taken the vice president of the United States to task when he condemned single mothers. She had more than earned the moniker emblazoned on one of the t-shirts available in her online merch store: Tanya Mother Tucker.

In demand for the first time in years, she slowly began playing higher-profile gigs. Tucker also returned to acting. (A little-known fact is that, as a child, she gave an affecting performance in a critical scene with Robert Redford in the film Jeremiah Johnson and later took acting classes with Lee Strasberg at the Actors Studio.) In September, she appeared in a cameo on the new television series Monarch starring Susan Sarandon, Anna Friel, and Trace Adkins, and she recently wrapped a six-week shoot on a holiday film.

Tucker has also expressed her appreciation to her gay fan base, who have stuck by her through thick and thin. An icon to rural queers since she first began recording, Tucker had become an ally in the 1980s—quite the risk for a mainstream country star these days, with the genre’s largely conservative fanbase, and even more so then. In Nickel Dreams, she movingly recounts her friendship with Michael Tovar, a hairdresser who came to be counted among her best friends, and his death from AIDS. Recent years have seen Tucker starring as a guest judge on episodes of RuPaul’s Drag Race; recording “This Is Our Country,” a twangy track with RuPaul that celebrates empowerment and inclusion; appearing at gay country singer Ty Herndon’s groundbreaking Concert for Love and Acceptance in 2020; and headlining the Nashville Pride Festival in 2022.

But her rekindled love for music remains her focus. She and Carlile, along with Jennings, have completed a highly anticipated follow-up to While I’m Livin’ that is set to be released in 2023. This time around, Tucker has recorded a duet with Carlile of “Breakfast with Brown Eyes in Birmingham,” a song given to them by the legendary Bernie Taupin. The pair have also continued their own writing partnership on a track that features one of Tucker’s finest vocal performances. Titled “Ready As I’ll Never Be,” the song offers a poignant, gospel-tinged reflection on her relationship with country music and all those she has lost—her parents, but also her heroes in the industry, like Loretta Lynn—and the process of pulling herself together in the wake of grief. Her voice, deep and resonant, glides over Jennings’s placid piano, a gorgeous pedal steel, and background vocals from Carlile and the Hanseroth twins, as she addresses all you outlaws and the Opry queens. The song’s placement over the end credits of The Return of Tanya Tucker offers a stirring coda to the film. To Horan, it’s a song felt in the chest, recalling Tucker’s early work, along with “a little TNT edge [and] a distinct Elvis gospel crescendo.” “Ready As I’ll Never Be” seems crafted to receive an Oscar nod for Best Original Song.

Like a character in one of the story songs she began singing all those years ago, Tucker has finally—almost—come full circle.

Years ago, when Tucker was raising hell in bars on Nashville’s Music Row, the legendary songwriter Harlan Howard told her she was “a writer trying to get out of a singer’s body.” Since then, Tucker has sometimes proven Howard’s observation true.

In the late Seventies, when she was recording her notorious rock record TNT, Tucker co-wrote “I’m the Singer, You’re the Song,” a tender ballad that reached the Top Twenty on the country charts and marked only the second time she had recorded one of her own compositions. After the now-classic barn burner “Texas (When I Die),” it’s the finest track on the album, telling the story of a young woman determined to defy the odds and reach the top, accompanied hand-in-hand by the boy she loves. We won’t hear a word they say, Tucker croons in her velvety, yearning voice. We’ll just do it our own way / And I know we’ll show ’em all someday.

Looking back, there’s more than a hint of prophecy in those words, which foretold how Tucker would chart her own course and confound the naysayers, and in other lyrics that follow: Ain’t had much time to look around / But I know I’ve found / A place in space where I belong / I’m the singer, you’re the song.

It’s clear that one place Tucker belongs is on the road. She thrives on touring and lives to be onstage. But after fifty years in the business, after millions of singles and albums sold, hundreds of concerts, there’s another place where she belongs.

The rotunda of the Country Music Hall of Fame is filled with legends—creative pioneers and artistic innovators who have made “significant contributions to the advancement of country music.” Connie Smith is there, inducted in 2012 as “one of country music’s premier vocalists.” So is Loretta Lynn, whom the hall celebrates as “one of country music’s most popular performers [who] broke ground for numerous female singers who followed her.” Tucker’s idol Elvis Presley is a member as well, honored for his country roots and “strong influence” on the genre and country charts “for his entire career.”

Garth Brooks and Alan Jackson are there already, despite the fact that they began recording almost twenty years after Tucker’s debut album was released. Randy Travis is there, inducted in 2016 for a career that began in 1985. Other stars of the Eighties and Nineties have been honored: Reba McEntire and Vince Gill and Ricky Skaggs. The Judds are there too, finally inducted in 2022 after being shamefully excluded for at least two decades—despite being one of the bestselling and most popular duos in country music history.

In considering Tucker’s exclusion from the rotunda, it’s possible that over the years her remarkable commercial success has counted against her, leading her to be dismissed as a mere hitmaker and entertainer, and not properly recognized and appreciated as the groundbreaking, influential artist she is. To some degree it’s an almost understandable error. Tucker is just so damn good, and she has been around for so damn long, that she has made it all seem effortless. And yet it hasn’t been. “I’ve been kickin’, fightin’, scratchin’ all the time,” she observes in The Return of Tanya Tucker. Later, she offers a revealing aside: “If I were to pay attention every time my name wasn’t mentioned I’d be upset all the time.”

The fact is that, like mainstream country itself, the Hall of Fame membership continues to be dominated by men, whose numbers outrank women to a shocking degree. Of its 175 members—a tabulation that includes individual members of musical groups—only twenty-four are women. For a genre and industry that was built on the sound of Maybelle Carter’s guitar, on the defiance of Loretta Lynn’s voice, on the lyrics of Dolly Parton, this is a travesty.

Even in the absence of this grossly lopsided gender disparity, Tanya Tucker merits a plaque on those walls alongside her heroes and peers, as well as the performers who followed in her wake, their paths made easier by the trail she blazed. If country music is indeed about truths expressed in unvarnished language with voices that pierce the heart, then Tucker surely ranks as one of the genre’s greatest storytellers.

Bring her flowers now.