In Old Wilmington

How the failed search for a silent film uncovered a lost musician of the Harlem Renaissance

By John Jeremiah Sullivan

Beauford Delaney (1901–1979) Untitled (Jazz Band), 1965, oil on canvas, 32 x 25 3/4 inches / 81.3 x 65.4 cm, signed; © Estate of Beauford Delaney by permission of Derek L. Spratley, Esquire, Court Appointed Administrator; Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York

John Jeremiah Sullivan's new column, “Fugitive Pieces,” gives space to ephemeral items that have turned up in his research.

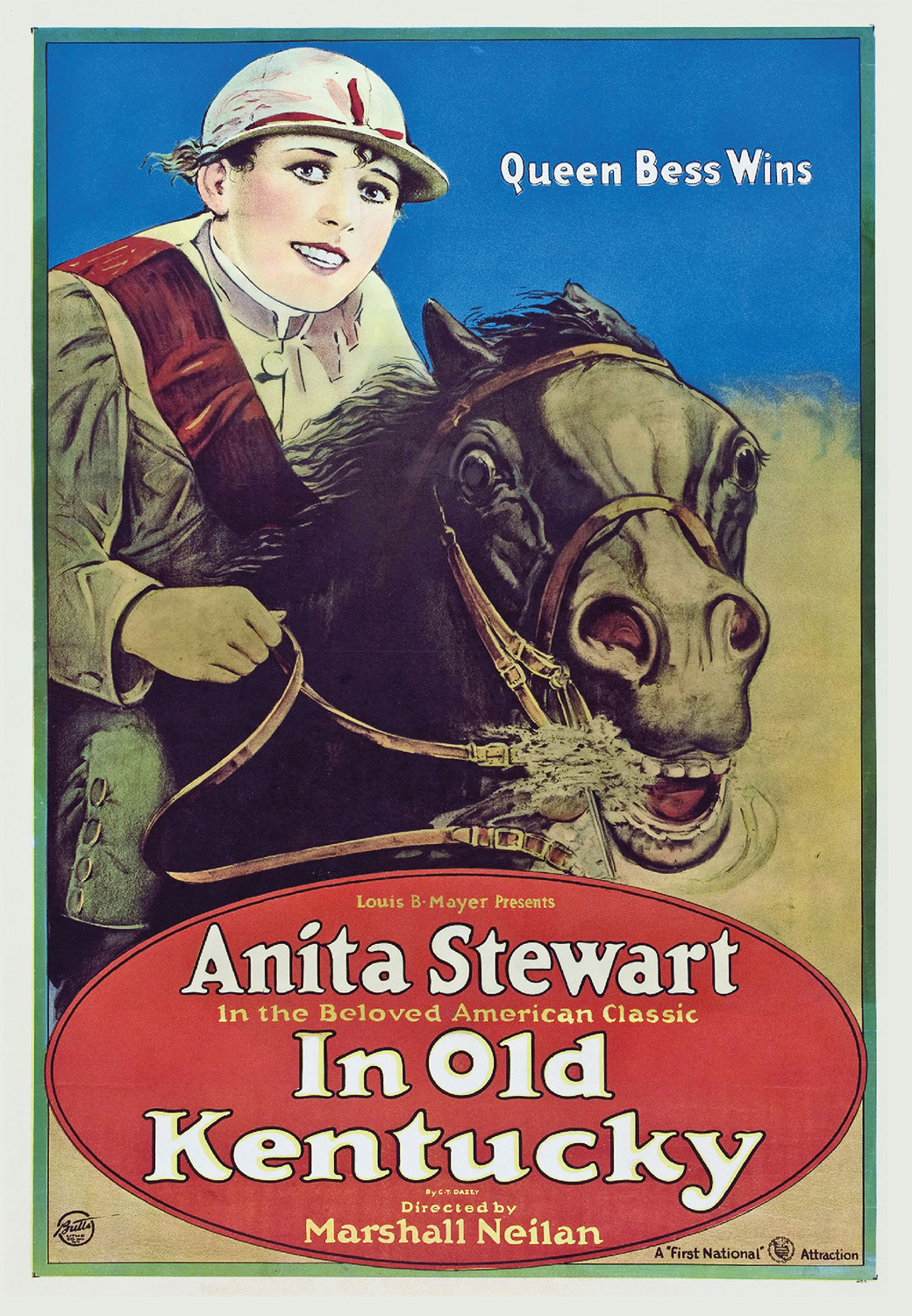

A few years ago, I got interested in a silent film from 1919 titled In Old Kentucky. A handful of period descriptions had led me to think that if a copy of the film survived, forgotten in a vault somewhere, it contained the earliest known footage (by at least a decade) of a Black jazz band performing. A few stray online comments by scholars of the early film industry indicated that a print did exist, preserved in one archive or another—an all but miraculous occurrence, if true, since the old silver-nitrate film stock on which those silent reels were printed is extremely perishable and likes to burst into flame—but it turns out that the film is in fact lost, or must be presumed so.

The way I learned of the film’s existence, or that it had once existed, was from a disturbing photograph in a 1919 issue of the early film magazine Motion Picture World. The picture shows a scene that took place in Wilmington, North Carolina, the city I’ve lived in for twenty years. An accompanying short article fleshed things out, slightly:

Although it is the closed season on “In Old Kentucky” stories, the stunt worked by D. M. Bain, of the Victoria, Wilmington, N.C., is worth the space. Mr. Bain knew of a local negro band of more than usual ability … When the picture came he put the boys on a horse drawn float and sent them out with a band of masked night riders to give concerts at the principal street corners. Wherever the band stopped the cavalcade drew up, and the sight of a band of masked men on blooded horses was almost as much of an attraction as the playing.

“D. M. Bain” was David Montrose Bain, a well-known Wilmington figure of the teens and twenties, the man in town to ask about anything movie-related. He had grown up in a flyspeck place called Harrelson’s Crossroads, about an hour west of town. In his teens he started working for the Wilmington Morning Star, our local paper (then and still), and eventually rose to the head of their circulation department. His colleagues considered him a “young man of sound business ability,” according to a profile of him that ran in the Star, “clever and industrious, obliging and courteous.” According to his World War I draft card he was tall and slender with dark hair and blue eyes. In 1911 he married Marcelle Smith, a druggist’s daughter. They eloped and very quickly had three kids.

Around 1915 Bain was hired as an “advertiser” by the Howard & Wells Amusement Company, which owned most of the theaters in the city. He was ambitious, not a person who just showed up for work. A photo of him was uploaded to Ancestry.com by one of his descendants. That’s why Motion Picture World was following him. The picture is from somewhat later in his life, although he did not live to be an old man, dying of colon cancer in his forties. Something went wrong with Bain. He’d divorced Marcelle and moved out to Rocky Point, up the river. When he died, he was estranged from his children.

What intrigued me most, on first encountering the Moving Picture World story, was the identity of that Wilmington jazz band, a “local negro band of more than usual ability” that Bain knew about in the spring of 1920. Why isn’t the band named? From a present-day perspective, it’s a painful omission. The history of jazz in Wilmington is sketchily documented. That’s the case with a surprising amount of Wilmington’s rich, nationally significant Black history. This city’s past has for so long been shadowed by the infamous racial massacre and coup d’état that took place here in 1898. That violence, and an ensuing exodus of Black families away from the city, opened a great crack of cultural disruption in Wilmington’s memory of itself, and all sorts of stories have fallen into it.

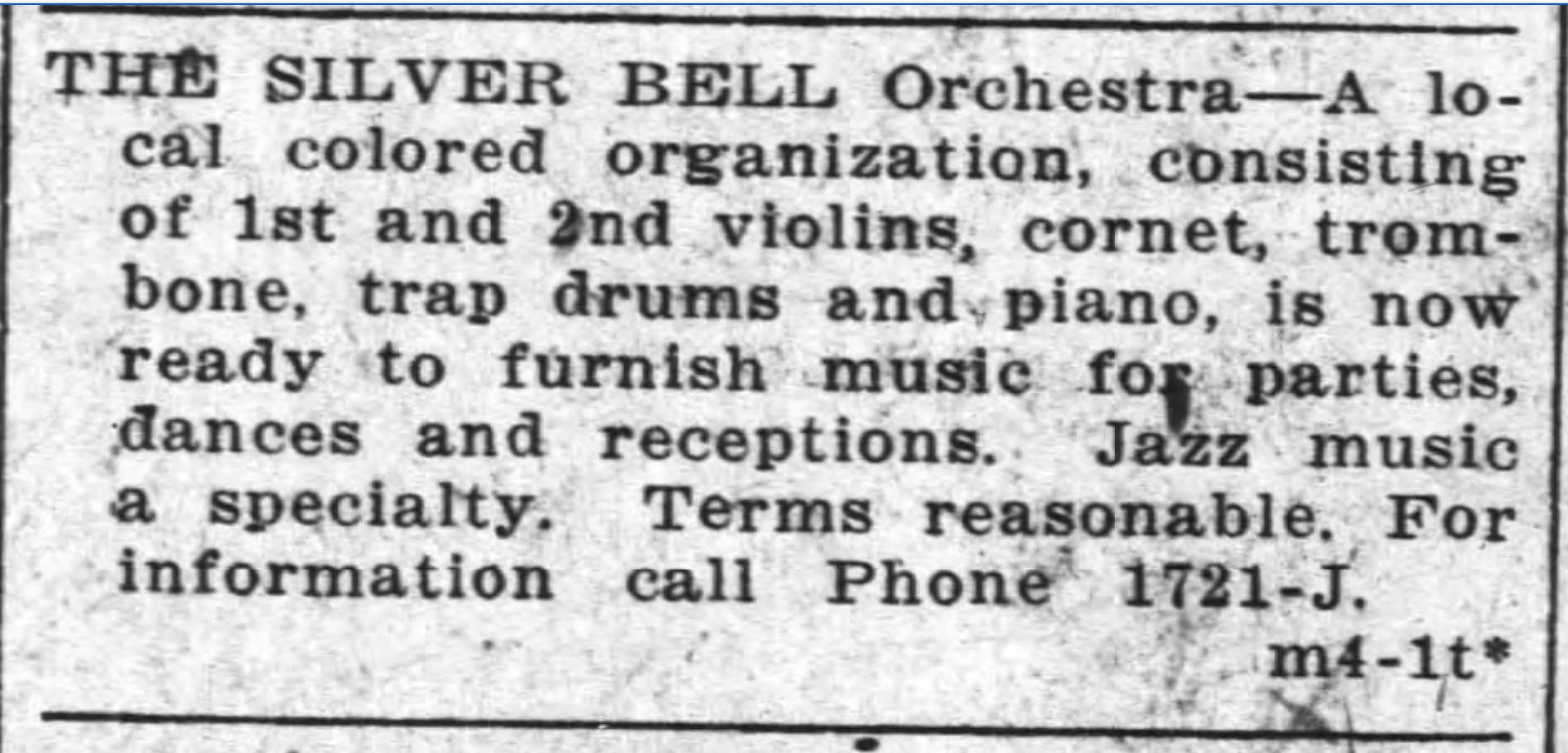

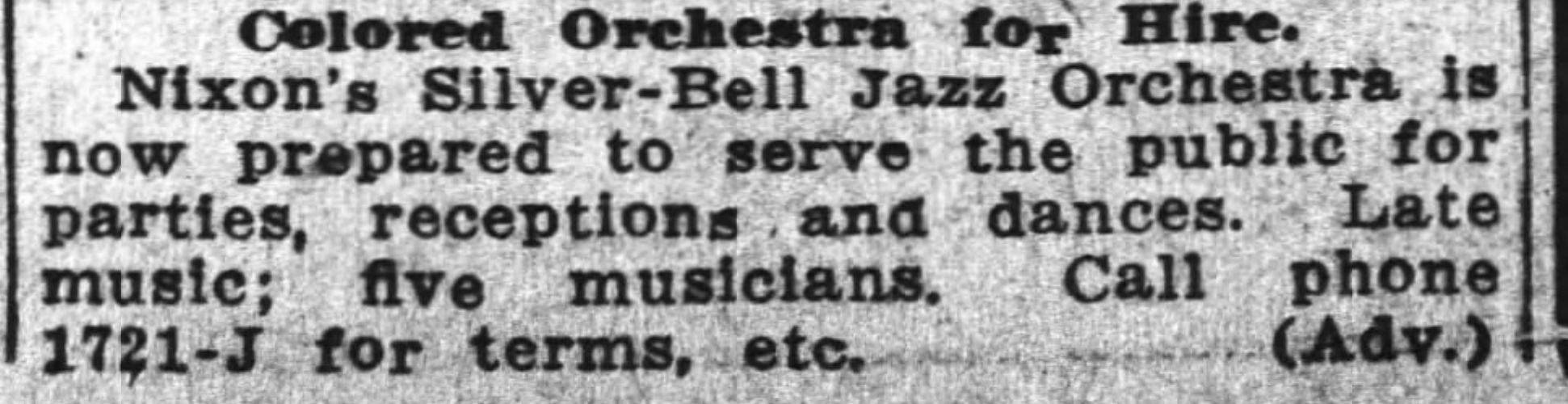

Nevertheless, it is possible to say with some confidence who was playing the music in the horse-drawn float that day, moving slowly through the streets while the horses, carrying hooded riders, surrounded the wagon as if in a phalanx. There was only one jazz band operating in Wilmington in the spring of 1920, or at least only one that has left textual traces.

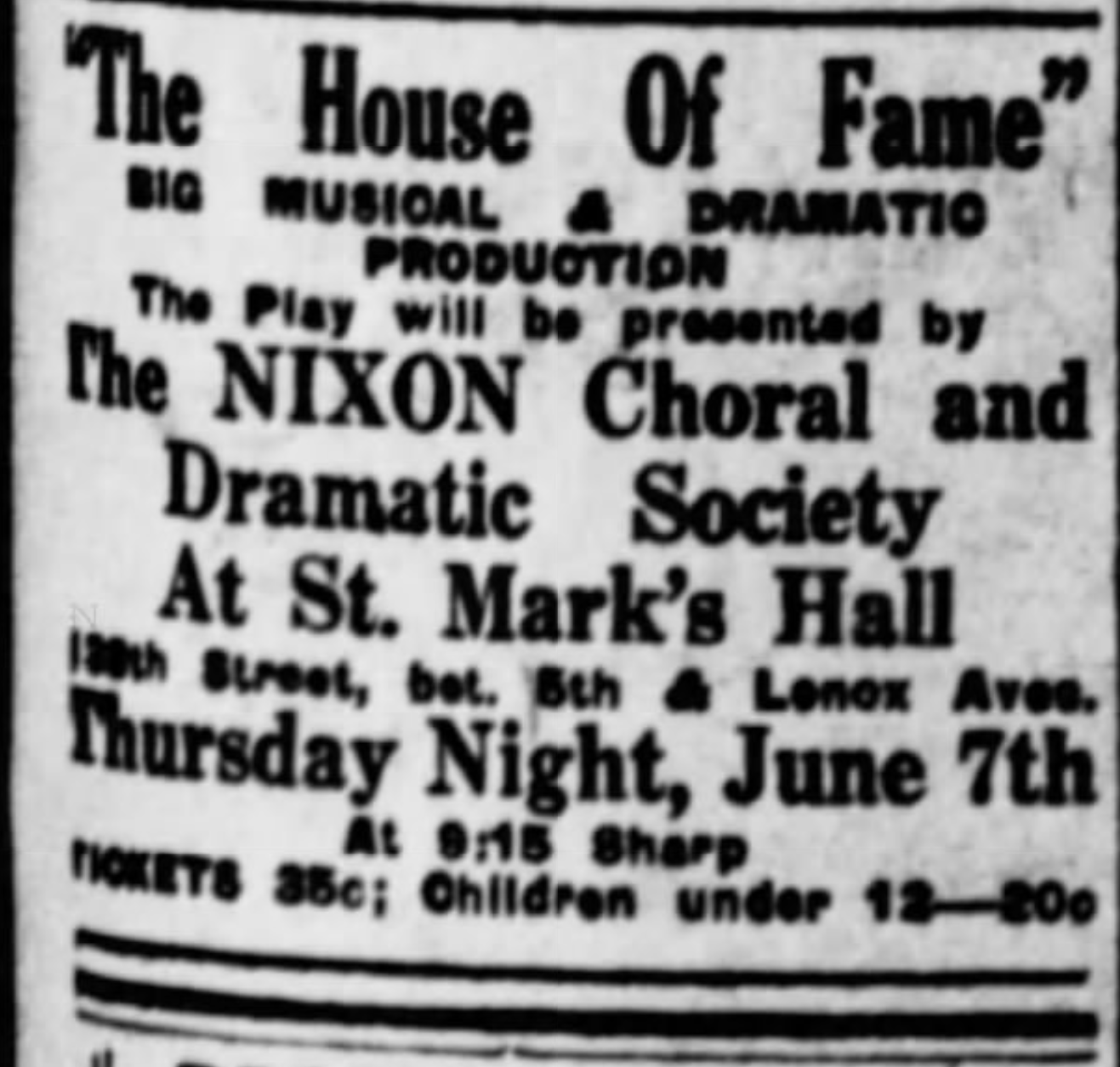

Here’s another classified ad, from later in the year:

This time we have a name, Nixon. Nixon’s Silver-Bell Jazz Orchestra. And it’s a “colored” orchestra, as the Motion Picture World article specifies. So, was there a highly skilled Black musician with the last name of Nixon in Wilmington in 1920 who can be identified in the sources—one with whom a suburban white guy like Bain might easily get in contact?

There was. His name was Arthur Eugene Nixon. The investigation of this photo gives us a chance to recover his extraordinary life. He was a pure product of the Black intellectual world that developed and flourished in Wilmington during the roughly three decades between Emancipation and the massacre of 1898. In fact, his father, John, who died when Arthur was still a teenager, had been considered by many a kind of unofficial mayor of that world. The Nixons were “a large, thrifty, and influential family,” according to an obituary of the father that ran in the New York Age in 1906.

From the April 3, 1920 issue of Moving Picture World.

John Nixon had been a vestryman at St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, one of the founding Black congregations downtown. When he died prematurely and left his sixteen-year-old son fatherless, a young preacher at St. Mark’s—a dynamic Antiguan man named Robert Bennett, who’d guided the flock through the horror of 1898 with a steady hand—took the boy under his wing. Bennett was the “first teacher and instructor” of Nixon, who as a child had been “a boy soprano soloist in Dr. Bennett’s choir.” (That’s from the Baltimore Afro-American in 1929.) It was in this early church context that Arthur began to study music and attempted his first compositions. He played several instruments but excelled most on the violin. In 1914 he was identified as “chorister” at St. Mark’s, which is to say, in this case, choir master.

In that same year, an original musical comedy Nixon had written was performed:

In 1917, he got married, to a young woman named Marion Hill. She was a few years younger. I have been unable to learn many facts about her life, not for lack of effort, apart from that she finished the course at Williston School in 1911 and St. Thomas, downtown, in 1916.

And there is this, which is probably, of all the little documentary flies-in-amber, the one that brings us closest to Arthur, and to her, for that matter: the announcement of their engagement, from November of 1916:

We get a faint sense of Arthur here. He’s “a good mixer” (easy to get along with). We know from his World War I draft registration card that he was tall and solidly built, with brown eyes and black hair. He and Marion both had “a wide circle of friends in several northern and southern cities.” They were not provincial people, certainly not provincial-minded. The very fact that their engagement was announced in the New York Age helps us to place them. They were extremely well-educated, and they had traveled. Arthur was, in short, just the sort of person to bring jazz to Wilmington.

In April of 1920, when David Bain needed a local jazz band to “boost” his movie In Old Kentucky, he could find the number for the Silver-Bell Jazz Orchestra in the newspaper. He wouldn’t have needed any Black music–world connections that he is unlikely to have had.

Look closely and you can see the fuzzy faces of a few of the band members peering around or over the banner, looking back at the camera.

“Night riders” is a somewhat ambiguous term. It can mean simply Klan. It can also mean “whitecaps,” i.e., one of any number of loosely organized vigilante groups throughout the South and Midwest who carried out lynchings and other sub-lethal acts of mob violence, typically racially motivated, for half a century. Here in Wilmington, when the massacre and coup of 1898 happened, we had a paramilitary group called the Red Shirts. They were basically night riders. Except they didn’t wear masks. That was part of the message they sent that day in November: We don’t have to wear masks. And they operated in the daytime. Of course, this grotesque little parade shown in Moving Picture World is likewise happening in the daytime. The overtones are so grim. And when you think about musical theft—this is the very city where the Black string-band tradition was all but physically stripped from its great master, Frank Johnson (a figure I spent years studying while writing about Rhiannon Giddens for the New Yorker). That music was handed over culturally to “old time” white players. It’s all too perfect, as metaphors go. You wouldn’t concoct it. It would seem at once too exotic and too obvious.

Luckily for our story—for its not being a total bummer—it doesn’t end there, and the real ending is the best part. Arthur Eugene Nixon spent a couple more years in Wilmington, but in 1923, when he was thirty-four years old, he and Marion moved to New York City, to Harlem. And in Harlem, obscure young Arthur Nixon of Wilmington became Prof. A. E. Nixon, a figure of real artistic importance. He opened a music-instruction academy, Nixon’s Music School, which featured Nixon’s Choral and Dramatic Society. It was among the most successful Black institutions of its kind in New York during those years, from 1923 into the 1950s.

Nixon was right there in the heart of Harlem when the Jazz Age and Harlem Renaissance were in full flower. He lived on West 137th, across from the Mother African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, aka Mother Zion. Within a very few years, the Nixon School was able to boast of “a large army of pupils.” Who knows who passed through his studio and under his guidance? The Nixon choir became famous. Reading through the old newspapers, you get the feeling that, in some years, a New Yorker was as likely to see them, at a major cultural event in the Black community, as not. In 1928 they were on the radio, on WABC, a program called Who’s Who in Colored America, which was “devoted to Negro Achievement.”

In 1927 the Nixon Music School choir did an “all-Negro musicale” at the Grace Congregational Church on West 139th. Nixon sang as part of that performance. He had a good baritone voice. His old friend from Wilmington, Felice Sadgwar, did a piano solo. The program focused on works by Black composers, and Nixon identified himself as a composer. He studied music during those first years in New York—at City College, Harlem Conservatory, and the Virgil School of Music. In 1929 a sacred cantata that Nixon wrote, “The Nativity,” was performed in six New York churches. The Baltimore Afro-American reported that it had been “lauded by music critics” in New York.

Somewhere along the way Arthur and Marion separated. In 1930 she was living with her mother. Neither ever remarried. In the 1950 census she is a “Nutrition Teacher,” working for the New York Health Department.

In 1947, in celebration of his “golden jubilee in the field of music,” Arthur Nixon conducted a high choral mass at St. Augustine’s Church on Lenox Avenue. Golden Jubilee, fifty years, meaning that he considered his musical career to have begun in 1897, the year before the massacre, when he was eight years old. That’s when the Rev. Robert Bennett had directed him as a boy soprano in the St. Mark’s choir. I think it’s beautiful that Nixon considered that his entry into the field of music.

The record starts to fuzz out as he ages. He lived a long time, into the 1980s, that is, into his nineties. No kids, no family in New York. People forget. I can’t figure out where he’s buried.

It strikes me that if the little rabbit-quest that kicked off this whole series of questions had succeeded—if the existence of the 1919 version of In Old Kentucky had been confirmed and I had been able to watch that “lost” footage of an early jazz band, the first ever shot—I might never have paid attention to those faces peering around the banner, in Wilmington, certainly not enough to get interested in the identity of those musicians, and so might never have known about A. E. Nixon, whose real life turns out to be at least as interesting as any sequence in a film strip.

The peak of his career came late, as it does for the luckiest. In 1952 and ’53 he directed large choirs at Carnegie Hall, on behalf of the Metropolitan Baptist Church. In 1953 the critic at the New York Age singled him out. Even if I could write a better ending I wouldn’t.

Of exceptional merit in Monday evening’s performance was the choir and the artistry of its director, A. E. Nixon. Mr. Nixon directed this unit with a type of finesse and dignity that brought prolonged and admirable applause from the audience of 3,000 which filled the main floor and the first and second balconies of the vast hall.