Language of Hunger

By Clarissa Fragoso Pinheiro

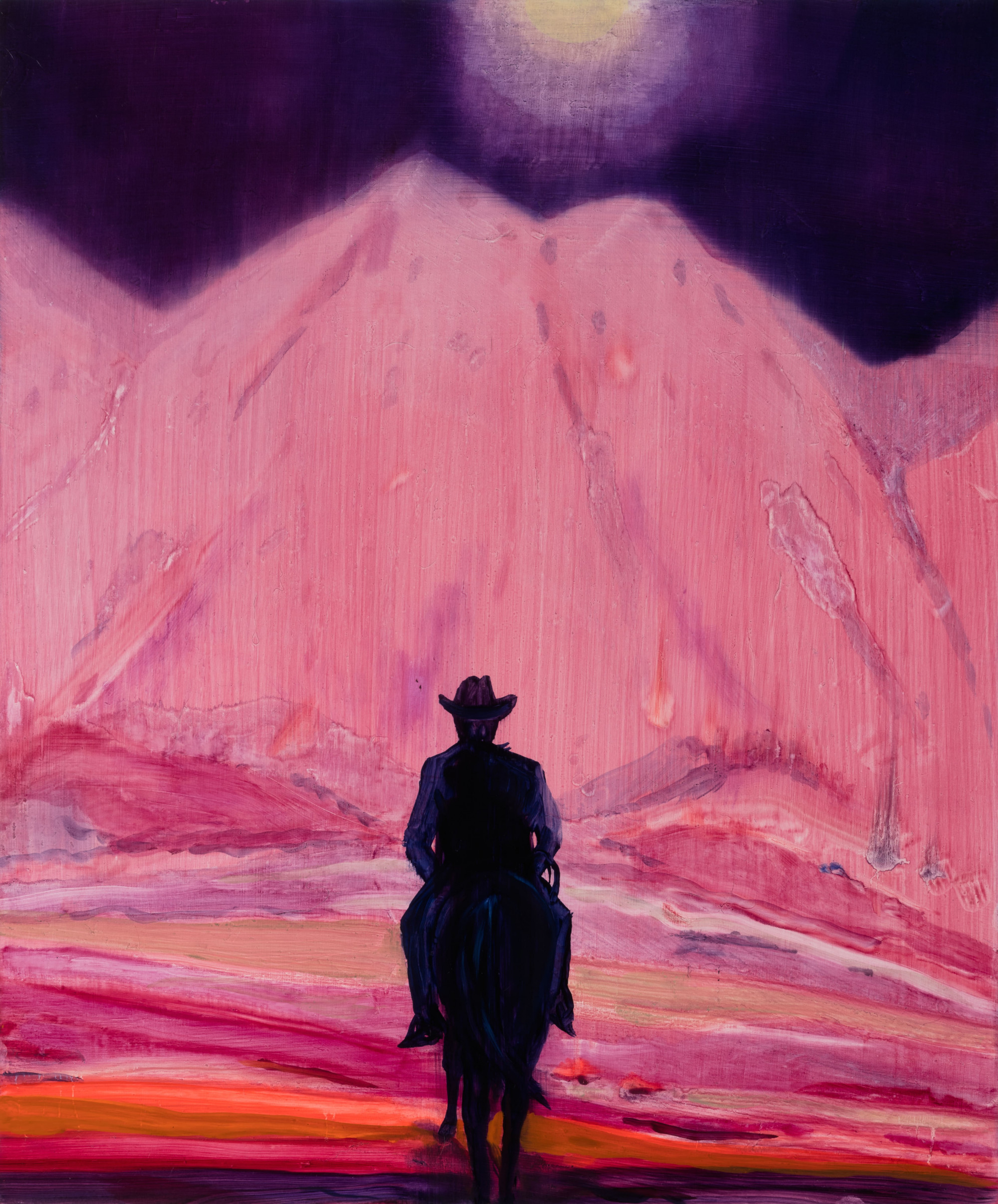

Looking for an Enlightened Cowboy, 2017, a painting by Jules de Balincourt © The artist. Courtesy Pace Gallery

After I finished high school, I did what a lot of Brazilians do: I moved to Canada to learn English. During my first nights in the small basement room of my homestay near the mountains of North Vancouver, I began an unusual ritual. I lay in bed with my eyes closed, tracing in my mind the details of my parents’ apartment where I had lived just a few days before. I started by slowly opening the door and noticing the dining room: the brown table with a glass top, the peace lily next to it, and the balcony where you could see a view of São Paulo. I tried to remember what it felt like to touch the furniture, to pull the long creamy curtains closed and sink into the black leather couch to watch a film.

I wanted to engrave every detail of home in my memory, so I retraced my steps through the apartment each night for several weeks, refusing to fall asleep until I knew exactly what home felt like. Later, I extended the ritual elsewhere—to my favorite streets in São Paulo or to the lines and creases on the faces of my loved ones. I longed to remember because I feared losing Brazil.

I left Latin America because I bought into the idea of English, believing that my country was insufficient and that this language was my pathway to a better life. But when I made this decision, I failed to anticipate the consequences of my choice.

To assimilate, I began to undo myself. I avoided spending too much time with Brazilians at school and stopped reading the few Portuguese books I had brought to Canada, though I couldn’t read books in English either. I no longer watched Brazilian films and replaced Portuguese subtitles with English ones. Before I noticed, I stopped retracing my steps. Assimilation required me to suppress my language and culture—it required me to trap the person I used to be within the body of who I was becoming. The more I settled into this new place, the more confined that old self became. The more my fear of losing Brazil turned real.

The Brazilian critic and director Glauber Rocha also began to wrestle with language at a young age, though his struggle had to do with the language of cinema. Born in 1939, in Bahia, Rocha grew up in a country dominated by the language of Hollywood. The most popular films in Brazil when he was a child were either low-budget comedies called chanchadas that parodied American musicals or imitations of American Westerns. Set in the sertão, a semi-arid region of the Northeast, these Westerns introduced the cangaço—a movement of social banditry—to world cinema. But to remain loyal to the original Westerns, these films, including the internationally acclaimed O Cangaceiro (1953) by Lima Barreto, sacrificed historical accuracy. They portrayed the figures of the movement, the cangaceiros, in the likeness of American cowboys—brutish and riding on horseback, even though the real cangaceiros traveled by foot. Rocha found these films profoundly inauthentic.

He was still in his teens when he started writing criticism for local papers. Much of his work condemned Brazilian directors for seeking commercial success by imitating Hollywood instead of depicting the reality of the Brazilian people. “[The Brazilian auteur] is castrated in relation to language, which is schematic, extrinsically prescribed as the grammar of American spectacle,” he wrote in 1963.

Rocha lived through an important historical juncture, which intertwined his creative practice with politics. As a child, he experienced the political tension caused by the Second World War and then lived through the Cold War. As a young adult, he saw the rise of social movements and lived through the CIA-backed military dictatorship in Brazil. Inspired by the idealism and radical thought of the period, Rocha saw Brazil’s loss of an original cinematic language as part of a political process—an outcome of colonialism. To him, the duty of Brazilian directors was to free themselves from their subjugation to Hollywood by developing their own language. “The first challenge of the Brazilian filmmaker is this: How can we win over the public without using American film forms?” he wrote in 1968. “Who are we? Which is our cinema?” With a group of young Brazilian directors that became known as the Cinema Novo movement, Rocha searched for answers. In the process, he developed a radical vision for Brazilians like me.

When I began taking my writing more seriously, my bilingualism tormented me. Nine years had passed since those days in the basement of North Vancouver. I was in my late twenties and preparing to relocate from Canada to New York to start an MFA program, in English. But I felt stagnant.

English was now my primary language. Yet I didn’t feel fluent, nor did I understand what fluency entailed. Ideas that once flowed through me with ease in Portuguese were stilted and lifeless in English. My thoughts came out fragmented, truncated. I began to collect false starts. I missed the intricate beauty and familiar rhythms of Portuguese, but I found them more difficult to access now that I had repressed that part of myself for nearly a decade.

So I started a different ritual this time: the one of desperately trying to rewind my life to the moment, years ago, before I said goodbye to my parents and friends in São Paulo. I wanted to undo what I had done to myself, to loosen the restraints trapping my old self within. I looked, urgently, for ways to reconnect with my culture. I began with Glauber Rocha’s Westerns.

Westerns are perhaps the most American film genre. In their classical form, these films romanticize American history and perpetuate the founding myths and values of American society, such as rugged individualism and the pursuit of freedom. The protagonist, typically a hyper-masculine frontiersman, travels through the vast landscape of the American West protecting the innocent, imposing his view of morality, and restoring order—often by violently eliminating Native Americans.

But Rocha’s Westerns were unlike anything I had ever seen. Rather than romanticizing conquest or distorting Brazilian history, Rocha appropriated the American genre, subverting its classic tropes to portray the reality of marginalized people. His films were deeply Brazilian, rooted in the history of the sertão, particularly the Canudos War and the social phenomenon of the cangaço.

The Canudos War erupted in the late nineteenth century in the backlands of Bahia. It began when a group of peasants, many of whom were former slaves looking to escape poverty, formed a utopian community in Canudos led by a messianic figure named Antônio Conselheiro. The Brazilian government launched four military campaigns to suppress the growing movement, resulting in Conselheiro’s death and causing one of the largest civilian massacres in history.

The cangaço offered an alternative to war for those living in poverty: banditry. The cangaceiros, commanded by a fierce leader, Virgulino Ferreira da Silva, known as Lampião, roamed the backlands stealing and murdering. But, as legend goes, they stole from the rich to give to the poor until they were captured and decapitated by the police in 1938. Both the utopian community of Canudos and the rise of brutal banditry revealed the poverty and oppression experienced by those living in the arid region as well as the extent of state neglect and brutality. The events exemplify Brazilians’ fight for better living conditions and their pursuit of autonomy and dignity. Lampião became a national folk hero, representing both social resistance and the dark face of marginality. As I write this, a small statue of him wearing his iconic leather hat and carrying a rifle sits on the bookshelf behind me.

The first time I watched Rocha’s Black God, White Devil (1964), I didn’t know what to make of it. Accustomed to the pristine and meticulous shots of John Ford’s Westerns, I was startled by Rocha’s unconventional aesthetic. The film opens with an aerial shot capturing the barren, sun-drenched landscape of the sertão, followed by a close-up of a cow’s rotting carcass. The creature’s lifeless eyes stare into the camera while a swarm of buzzing flies feasts on the remaining flesh. The scene is harsh, quiet, and violent, unlike the majestic mesas and vast plains shown in the opening shots of American Westerns like Stagecoach (1939) or The Searchers (1956). Here was a Western set in a land not of potential prosperity but of decay and misery.

Released a few months after a military dictatorship took hold of Brazil, Black God, White Devil is set a few years after the Canudos War and the death of Lampião and his band. The film depicts the religious and violent past of the sertão through the story of Manoel and Rosa, a poor peasant couple forced to flee through the harsh region after Manoel kills his boss in a payment dispute. As they travel, they encounter characters who reflect the oppressive forces of their society. These forces are embodied by the powerful landowner (Manoel’s boss), a messianic figure called Sebastião, and Corisco, one of the last cangaceiros alive. They also meet Antônio das Mortes, a hit man hired by the local government and the Catholic church to suppress a peasant insurrection or the return of the cangaço. His role is to kill Sebastião and Corisco.

Disregarding Western conventions and narrative symmetry, Rocha creates a film with obscure poetry. Imaginative symbolism distinguishes the film’s dialogue, and the story is told through a singer-narrator, an homage to the popular cordel literature of the region. To reflect the reality of these characters, Rocha embraces visual discomfort. The camera jostles and shakes; scenes are deliberately overexposed to create the feeling of a hot, sunny land. Spectators witness both a baby sacrifice and genocide, but unlike the moralistic brutality of American Westerns, the violence in the film is but a consequence of the misery experienced by the characters. The result is a film that feels both surreal and hyperreal.

Black God, White Devil captures what Rocha came to call “the aesthetics of hunger.” The hunger Rocha refers to isn’t only the physical hunger felt by those living in misery but a more profound or metaphysical hunger that impacts colonized people—those who haven’t been allowed to develop a language to articulate their reality. Or as he wrote: “Herein lies the tragic originality of Cinema Novo in relation to World Cinema. Our originality is our hunger and our greatest misery is that this hunger is felt but not intellectually understood.” He believed that the purest manifestation of hunger is violence; therefore, an aesthetic of hunger comprises the aesthetic of violence. Only through the depiction of violence would the colonized be awakened to their condition and the colonizer be made aware of the colonized.

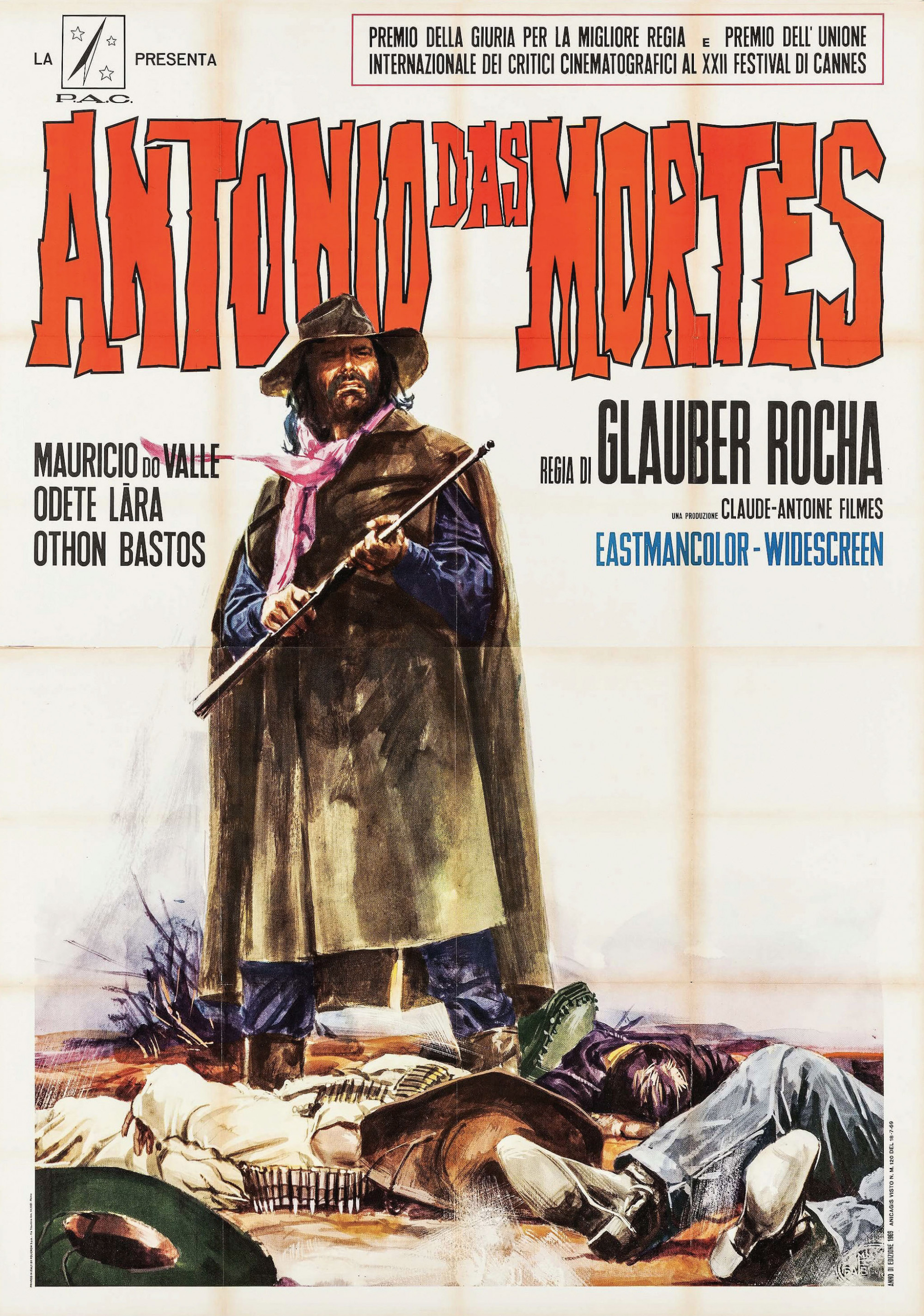

In Rocha’s second Western, Antonio das Mortes, we meet the title character again, years after his encounter with Manoel and Rosa and what he thought was the end of the cangaço. He has retired, but the colonel of a small town in the sertão wants him to complete a final job: to kill a man called Coirana, who claims to be a new cangaceiro with a large following. Antônio accepts the task but refuses payment. He agrees to search for Coirana because he cannot believe he failed to end the cangaço. The protagonist is lost, experiencing an existential and spiritual crisis that will eventually transform him into a rebel himself.

Like Black God, White Devil, the film is extremely inventive. Take, for example, a standoff that happens when Antônio das Mortes finally confronts Coirana face-to-face. Instead of remaining silent, like most men in American Westerns, Coirana recites a list of demands that, in Portuguese, rhyme like a poem. He says: “Prisoners will be released, and jailers will be locked up. Prostitutes will get married in the church wearing wedding veils under the full moon. I want money for my misery, and food for my people.” When he is done, he leaps and twirls like a comic madman. Instead of drawing their guns, the two men brandish machetes; a pink cloth between their teeth measures the distance between them. In the scene, the tension escalates through the incessant Afro-Brazilian chanting of the peasants, not through the actions of the two men. When Antônio das Mortes finally stabs Coirana, the chanting grows even louder. Then a close-up of Antônio’s face captures his regret.

Entranced by the rhythms and colors of my country, I first watched this violent scene in tears. Seeing Antônio’s face stiffen with remorse and watching him succumb to anguish throughout the film awakened in me a connection to Brazil that had long seemed dormant. For most of his life, Antônio detached himself from the roots of his culture, aiding those who tried to subdue its power; by suppressing Portuguese, my native tongue, and my culture, I realized I had done the same.

For Antonio das Mortes, Rocha won the 1969 Best Director Prize at Cannes. In 1971, as the military dictatorship grew more oppressive, Rocha joined other Brazilian artists in exile, moving throughout several countries. He never permanently returned to Brazil, and with his departure, the Cinema Novo movement dwindled, becoming only a part of history. During his exile, Rocha wrote criticism and directed four films, but critics considered the period mostly unproductive and riddled with political controversy.

Isolation and a lack of resources for his films took a toll on Rocha. In letters, he mourned his separation from his mother, friends, and Rio’s cultural scene. He was lonely, struggling to make ends meet, working day and night as a critic to pay his bills, and relying on the support of European friends. In a final desperate act, in 1974, he wrote an article praising the military junta of President Ernesto Geisel. It was an attempt to secure a possible return to Brazil and, with it, state funding for his films.

His plan succeeded. In 1976, Rocha briefly returned, but he was now ostracized by the Brazilian left. He soon began working on what would be his last film, which was funded by a state-owned company, further infuriating his critics.

Released in 1980, The Age of the Earth lacks a narrative structure or clear form. It was conceived as a blend of fiction and documentary, and without a preassembled order; unnumbered film rolls were shown at the discretion of the projectionist. The central theme is the global struggle against imperialism, the force of which is personified by an evil American. An anti-Hollywoodian poem of sorts, the film is Rocha’s most ambitious attempt to deconstruct cinematic language, to strip it down to its purest and most original form. Despite his innovative vision, it was poorly received by critics at the Venice Film Festival. The American director George Stevens Jr., for instance, called it “2 hours and 45 minutes of ranting chaos.” Enraged, Rocha reacted by organizing a march at the Lido and accusing jury members of selling themselves to capitalist Hollywood.

Feeling misunderstood and further isolated, Rocha left for Portugal in 1981. But after becoming suddenly ill, he returned to Brazil in August in a comatose state. He died in Rio twenty-four hours later at the age of forty-two. His doctors attributed his sudden death to a lung infection, but his mother believed he died of another ailment: “He died of sadness,” she said in an interview. “My son died of Brazil.”

Perhaps her somber assessment captures more precisely the issues that ignited him—that led him to try so intensely to articulate his, and our, hunger.

Hundreds of weeping artists surrounded Rocha as he was buried. His death softened the blow of his final years, and despite the failure of his last film or the fact that he never drew a large audience to the theater, Rocha is still considered one of Brazil’s most important filmmakers. As anthropologist Darcy Ribeiro said at his funeral, “Rocha’s films were this: a lament, a cry, a scream. What remains of Glauber is the legacy of his indignation.”

Throughout his life, Rocha resisted the forces that led me to abandon my country and language in search of another, and that made me believe my life’s worth was attached to my ability to belong to someone else’s vision of the world. I don’t know what to make of his tragic end or how to measure his success. Rocha insisted it was possible for colonized people like me to transcend the creative stagnation caused by “the unconscious admiration of colonial culture.” But his radical idealism led him to die misunderstood and isolated—and Hollywood certainly won the dominance over cinema’s language. Perhaps his complicated legacy is a testament to his success, the price he had to pay to remain true to himself.

My truth is that I don’t know if I am willing to sacrifice as much as he did, and I’m not sure what that says about me as a writer, or as a Brazilian. What I do know is that since I watched his films, home feels closer. Whenever I reflect on our shared struggle to find a language, I think back to my initial reaction to the chanting of Brazilian peasants as Antônio das Mortes plunges his blade into the cangaceiro. It makes sense to me now that I would cry.

From the place in my body where I have trapped Portuguese, a memory surfaces. I am in a classroom with a group of children learning to sing and clap to the rhythm of a song composed by the bandit leader, Lampião: Olê muié rendeira. Olê muié rendá. Tu me ensina a fazê renda. Que eu te ensino a namorá. Olê muié rendeira. Olê muié rendá. Tu me ensina a fazê renda. Que eu te ensino a namorá. And with this memory comes another. My cousins are playing capoeira in my grandparents’ backyard. I’m sitting on the grass watching them. I look down at my little hands. I’m singing. I’m clapping. I’m back in Brazil.