Imagining Through Fabric

The textiles and memories of Cameroon's Muna Moto

By Qaman Omar

Romeo & Juliette 1, 2022, a painting by Fosso Jometio Féraul (Feraul Fosso). Courtesy the artist

It was the early 2000s, and I had no real interests aside from observation. While my siblings played group sports, I would sit on the park bench or the gritty asphalt, watching the promenade of elderly neighbors, the runners, the stroller pushers, the smokers, and the readers. I spent much of my preteen years simply looking—at magazines, at family photo albums, at the Bollywood and Nollywood films that my parents adored, which left me breathless from their sheer amount of visual information. More than anything else, I was looking closely at textiles.

Like every Somali woman, my mother holds a tacit kind of glamour that’s grounded in a deep knowledge of textiles and their make. As a pastime and an education, I watched my mother, her sisters, and their friends unfasten weather-beaten trunks that had endured the trek from East Africa to the American Midwest. The leather trunks were filled with stretches of linen, chiffon, organza, embroidered silks, and African wax prints stuffed into rectangular cellophane pouches. The women would methodically examine the stock, perfectly curated from textile markets in major American cities with larger Indian Ocean diasporas, namely New York and Chicago. They would grasp at the fabrics, tweaking and rubbing them to get a feel for their composition. The women were incredibly discerning, textile specialists unto themselves—“That’s an ikat from Indonesia.” “This is called a paithani brocade.” Scenes like these often went late into the night, with endless cups of spiced black tea, cross-continental gossip, and dance interludes to the Dur-Dur Band tracks of their youth. Even after being sent off to bed, I’d stay up and listen to their discussions. Based on their poetically descriptive dialogue, I would often animate my mother and her guests’ conversations, casting them in short films in my head. I lulled myself to sleep with cinematic images of these imaginary temporalities, populated by the women in the next room. Like my mother and aunties, I envisioned ways of living, remembering, and imagining through fabrics and the culture around them.

Over the years, my childhood connection to fabric has developed into a scholarly interest in how textiles—the labor of their production, their use, and their manifestations in art history—can ask and answer questions about aesthetics and politics. Cinema, as a portal for the sensorial, emerges as particularly fertile ground for exploring the feeling experience of textiles. And seldom does a film have as much ardor for how textiles are lived with as Cameroonian director Dikongué-Pipa’s 1975 feature Muna Moto, which translates to The Child of Another. (Dikongué-Pipa has since renounced the first name that the film’s credits list for him.) In late February 2020, days before COVID-19 stay-at-home orders would take effect, I attended the premiere of the newly restored film, part of the Wexner Center’s Cinema Revival program. The African Film Heritage Project, the brainchild of the auteur Martin Scorsese, along with other film organizations in Africa and Europe, painstakingly conserved and restored Muna Moto from existing 35mm prints, allowing the rarely seen early work of African cinema to be experienced by new audiences.

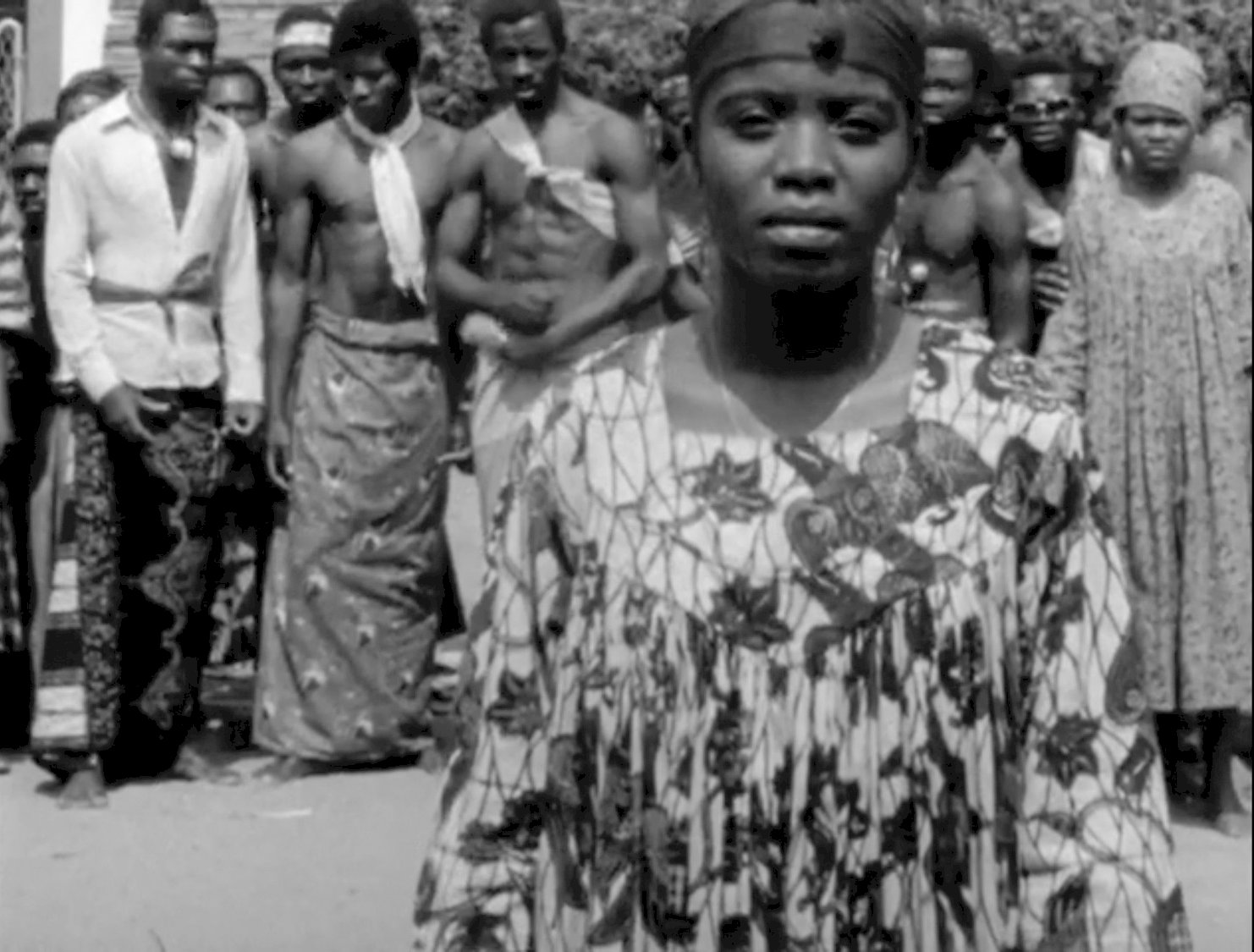

The film follows Ngando (David Endene) and his passionate courtship with, and ultimately doomed betrothal to, Ndomé (Arlette Din Bell). Ngando, a day laborer with a gazing expression, is at an impasse. He desperately wants to marry Ndomé but is stymied by his inability to provide an appropriate dowry to her parents. Ndomé’s father sets a high dowry hoping to ease the impact of the exponential inflation plaguing Cameroon in the wake of European colonialism. The dowry tradition, once a symbolic gesture, had become a means of income for Cameroonian families bound by France’s enduring economic domination in the country even after it gained its independence in 1961. The film uses the melodrama of Ngando and Ndomé’s corrupted engagement as a microcosm that presents a polemic against the colonial perversion of intimate life. Dikongué-Pipa wrote Muna Moto in 1966, just five years after Cameroon’s independence, but couldn’t begin production until nearly a decade later due to funding issues. His film captures a moment in Cameroonian, and African, history in which experiments of living outside of the colonial context were being undertaken.

One place where Dikongué-Pipa most potently captures that moment is in intimate experiences related to textiles. He constructs his thesis on the African cinematic language by revealing the granularity of lived experiences on the continent. In one scene, Ngando’s mother makes a modest addition to the dowry with a length of well-worn, paisley-printed cotton and simple earrings. I was struck by how the film establishes the passage of these heirloom materials—not only as sufficient to their purpose, but as true to precolonial custom. Later, Ndomé is seen with her head wrapped in that same cloth even after her engagement to Ngando falls apart.

Still from Muna Moto

Looking back, I now recognize that my own family’s relationship with fabric contains traces of the complex economic history of Somalia. My mother and aunties knew how these fabrics were made on the loom, understanding their precise warp and weft formation. This intimate knowledge was likely inherited from Somalia’s long historical encounters with South and East Asian textile producers. With its auspicious location on the Indian Ocean, materials have passed through Somalia for centuries, leaving textural residues behind that inform how most Somalis dress today. The wax prints worn by my mother and most African women were evidence of the textural exchanges of colonialism on the continent, having actually originated in the Netherlands as imitations of Indonesian batik. The fabric took hold in Africa’s larger material culture as it was sold back to West African consumers en masse.

But, as it does with my family, fabric in Muna Moto also holds more personal memories. Dikongué-Pipa complicates the established image of Africa with both searing verité, revealing unvarnished truths of life in Cameroon, and with rhapsodic reverie. Ngando’s wistful dreams of Ndomé are the film’s most textile-involved moments. A linen shirt hangs, threadbare, above Ngando’s bed. The camera drifts from the shirt and the shadow it casts on the wall to Ngando’s now despairing, entranced face—as if his memories are accessed through the textiles that remain. Textile and memory have always been entwined in African culture, as I experienced firsthand in my little Somali enclave in Ohio. My mother and aunties would organize those living room gatherings, sorting through their fresh trove of textiles while remembering their shared past and making designs for their futures: “Did you know I was gifted five yards of block-printed silk for my wedding in 1985?” “This will go perfectly with the scarf I will wear to my son’s wedding!”

Dikongué-Pipa organizes Muna Moto around a handful of daydream sequences that, astoundingly, look a lot like my own did. I left the auditorium reoriented. I had just seen a film that, with incredible subtlety, echoed my understanding of textiles as totems of memory. Muna Moto shattered my arrogant assumption that the mythical cinematic mode of my childhood was unique to me and my preoccupation with close looking. My archival and art historical practices have been forever inflected with the profoundly realized images of textiles in the film. Years later, I remain under the spell of Muna Moto, searching for other imagery that centers on the feeling-quality of textiles, affording them a cinematic language.