Unspooling Norma Rae

By Kit Duckworth

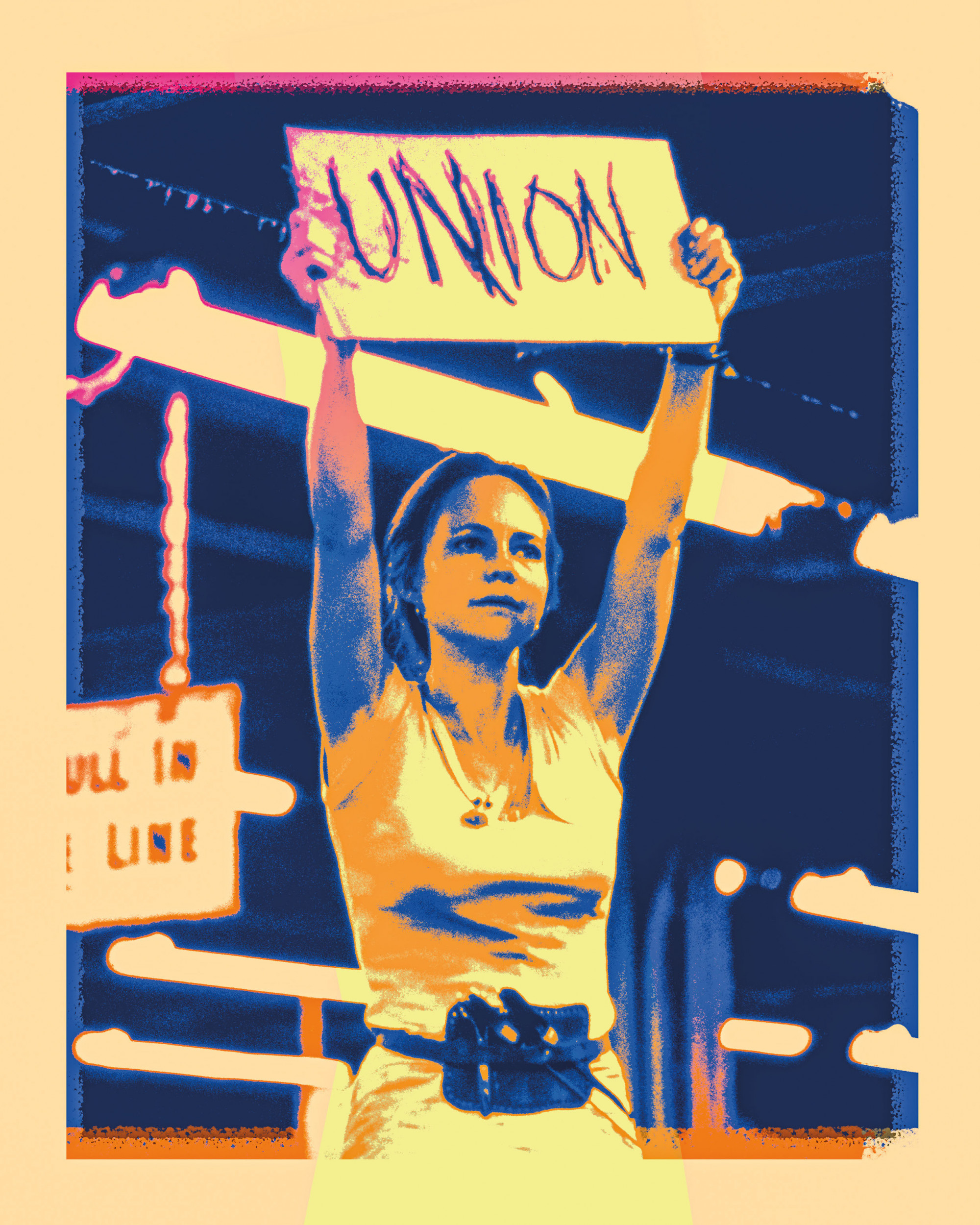

Sally Field in Norma Rae, 1979 © 20th Century Fox. Courtesy Everett Collection

Sometimes a single word can unfurl a whole history. For me, one such word is spool. Mawmaw, my maternal grandmother, wound thread around wooden spools, wound ink ribbons around typewriter spools. For years she scrawled diligent shorthand and typed up documents as a secretary in western North Carolina. Up north, another, anonymous secretary took the minutes for textile executives seeding stratagems against organizing millhands, mostly women (though called “girls” by their bosses and the classifieds, as in “girls wanted”). Some of these women rang the typewriter bell late into the night, keying union pamphlets so that underpaid workers need not pilfer their curlers from the five-and-dime, where shopgirls propped their bored chins up behind checkout counters until a patrolling manager made them stand straight and smile.

Mawmaw’s hair hung straight in childhood photographs but waved in those taken around her engagement, in 1955, when one brand on the shelf was Spoolies, favored by working women because the curlers could be left in while they slept. Come morning, the mirror would reflect how they wanted to be, or to be seen, just in time for them to clock in. The language of femininity coils: cotton and hair, labor and leisure, a living and a life.

In Martin Ritt’s 1979 film, the eponymous Norma Rae seems to have no time for curlers, or anything else. She lives with her parents, who work with her at the O.P. Henley Textile Mill in their small North Carolina town, and two kids whose two fathers are gone or worse, popping up pointlessly to beg off duty. She wears worn denim and scoop-neck tees, sweat-streaked because the windowless factory floor intensifies the stifling Southern heat. Often she pulls her hair up in a loose bun, lifting it clear of the thrumming looms—perilous to locks and limbs, and liable to catch fire from the kindling lint. Hence the pejorative “lintheads,” from the way cotton drifts, downy as doves’ feathers, cling to the body long after a shift has ended.

Work isn’t so easy to shake off. To rendezvous with her married lover, Norma Rae swiftly brushes out her hair, swaps shirts, slathers perfume across neck and chest—all sans sitting down. One evening she tells him it doesn’t “feel good” anymore, and we understand her dissatisfaction as something beyond sex. The man, humiliated, aims to humiliate in turn: “Why, you hick. You got dirt under your fingernails. You pick your teeth with a matchbook. I’ve seen your shit… You come outta that factory, wash under your armpits…and you’re dumping me?” In other words, she doesn’t deserve to say no. To him, Norma Rae is classed by her failure to meet gendered codes of propriety, and her class renders her disposable, a four-syllable synonym for trash.

Millhands are considered “trash, to some,” Norma Rae later explains to Reuben Warshowsky, the labor activist recently arrived from New York to help unionize her recalcitrant cotton mill. In the same conversation, he teasingly lists her so-called assets to the cause—“smart, loud, profane, sloppy, hard-working”—but her ears snag on “sloppy,” provoking playful protest. It’s a funny comment: Who would know better than himself that she, as common parlance goes, “works for a living”? In fact, they’re both sporting t-shirts and jeans, her from practicality and him in hippie-ish imitation of workwear, the distinction between sloppiness and style a matter of whether one can choose to play against type. (After all, Hollywood adores awarding actresses, like Sally Field as Norma Rae, willing to shed some of their polished poise on-screen.) The one time Norma Rae gussies up for a date, donning a red-and-white polka-dot dress with a sweetheart neckline, the effect is of an onstage costume change, like that of a keen contestant in a state-fair beauty pageant. And she does win the prize, a good-enough husband who promises, in lieu of romance, the one thing a man has never given her: commitment.

But Norma Rae’s commitment to the union is something she gives herself, and that no one can take away. One day Reuben, intending to pursue legal retaliation against the company, asks her to transcribe a bulletin alleging Black union members would dominate the mill and, by sly implication, their white coworkers. Norma Rae, who knows her bosses can’t technically fire her for organizing but can drum up some specious excuse to do so anyway, jokes that the task reminds her of when she shoplifted a lipstick from the five-and-dime. Nervously, Reuben asks if she got caught. No, she says: “I went back for curlers!” The line isn’t merely cosmetic. With identical gestures Norma Rae grasps for the union and for some dignifying scrap of glamour, by whatever means are at hand. This is her “bread, and roses too”—mere subsistence is not enough.

Throughout the twentieth century, women were both the primary creators of commercial textiles and their primary consumers, though not often the same women at the same time. And yet they dwelled alongside one another, sometimes jarringly. If a woman at home in curlers opened the Charlotte Observer one day in 1937, she could gaze dreamily at an image of Olivia de Havilland—who would soon star as Melanie, the soft-spoken Southern belle in 1939’s Gone with the Wind—her lithe leg parting swaths of inked fabric. Below: “According to a cable from Paris, shorter skirts continue to be the highlight of fashion.” Then the woman’s eyes might wander down to a bulky advertisement for a Southern department store, boasting bargains on cotton muslin sheets. A narrow column would be squeezed on the page, which an idle reader might not even notice, never mind peruse, about a mill strike in Granite Falls and Hickory, North Carolina: “Distribution of food supplies to ‘emergency’ cases among strike families…was begun today…[by a] relief agent of the Textile Workers’ Organization Committee.” Were these blithely arrayed products woven by someone who—forget skirts, sheets, curlers—didn’t have enough to eat?

For some time Mawmaw’s mother, Ma Hall, worked at a hosiery mill in Granite Falls, during the 1937 strike, for all I know—she died before I was born. She must have been aware of it, could even have numbered among the striking or stricken millhands. I wouldn’t have thought to ask, even if I could have. For most of my youth, “union” suggested only marriage, “to form a more perfect,” and the blue-uniformed foes of the felled soldiers frozen in marble and granite outside Southern courthouses. Connotation can count for a lot in lives laden with history. When Reuben first knocks on their door, Norma Rae’s father fusses him off: “Every time you people come into town, folks get throwed out of their jobs, they get their heads busted in.” This isn’t, or isn’t only, bigotry; it’s also brute fact. Even Norma Rae, explaining local resistance to his overtures, labels Reuben an “outsider.” Easier to pretend the “threat” comes from “you people”—Jews, communists, union organizers, or all of the above—than stake a desire for more and admit the near impossibility of getting it, both of which leave one vulnerable. One editorial from 1937 read: “Bloodshed follows a Southern textile strike almost as inevitably as night follows day.” There’s little doubt which side was doing the bleeding.

Everywhere there were warnings of what workers could lose, and what they couldn’t afford to. In 1929, Ella May Wiggins, a pregnant mill worker, was shot to death en route to a union meeting in Gastonia, North Carolina. The unwed Ella May had long endured prurient gossip about her fatherless children and, in reply, banked on her more sympathetic status as a mother, as in her famous ballad “Mill Mother’s Lament.” Likewise Norma Rae sits her children down, in one scene, to detail their checkered parentage, fearing her union involvement will subject them to mockery and rumor. The moment is dual-purpose: to humanize her putative indiscretions while reminding viewers she’s a matriarch first. But it wasn’t enough to pose as a perfect victim. In 1934, the year Mawmaw was born, the General Textile Strike sparked up in Tennessee and in North Carolina, where the governor ordered the National Guard to murder any “Pickets”—as scornful newspapers othered them—trying to “infiltrate” the mills. The strike snowballed into the largest of its kind in American history. But absent institutional support, millhands trickled back to work. This time, the union was defeated in the South.

In many areas of the region, mills formed the fabric of everyday life. There were mill company towns and stores, company softball teams; the foremen could be church deacons or next-door neighbors. Norma Rae taunts one neighbor to spy through her freshly scrubbed, un-curtained window while she holds a multiracial union meeting in her cramped living room. By 1973, one out of every five Southerners in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, Florida, Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi were employed by a textile mill. So reported a 1973 New York Times article headlined “Trouble in the South’s First Industry,” which described the struggles of North Carolina millhand Crystal Lee Sutton—whose life more than inspired the character of Norma Rae.

Sutton was one of many who worked to unionize one of the seven mills in her hometown of Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, run by J. P. Stevens, a notorious offender before the National Labor Relations Board. Stevens’s mills had entangled Sutton’s family, as they did many others. When an irate Norma Rae complains of her mother’s hearing loss due to the thundering machines, she’s told to get another job. She counters: “What other job in this town?!” Sutton’s parents were both mill workers, and she had witnessed its impact on their minds and bodies, from alcoholism to brown lung, a disorder in which minute cotton fibers lodge in the chest and progressively strangle breath. In high school, she sought escape by enrolling in shorthand classes, which would place her in a quieter, cleaner, more lucrative office, but felt too exhausted after school and her night shift at the mill to study. She was then only seventeen, and her family needed the money. She dropped the classes.

By working at a hosiery mill in Hickory, Mawmaw paid her way through business college, where she did learn shorthand, invaluable in her lifelong career as a secretary. Such a slim line separates lack and luck, that sliver of circumstance that shakes us free of inherited patterns. But Mawmaw was also seeking escape. She was raised on a farm where her five-person family grew cotton, which paid back their rent and afforded them clothes, books, shoes, and not much else; they grew most of their food but craved sandwiches of thick tomatoes on pillowy, store-bought white bread—the lunch of rich folks’ children. For the many Southerners who still worked the land, the proliferating mills provided opportunities for better living conditions and higher pay. If cotton was in their hair, anyway, better to not have dirt caking their boots, too.

After the devastations of the Civil War, most textile mills were located in the more industrialized North and only moved south to chase lower wages, given the region’s laxer labor laws. Southern mill workers in the twentieth century were often paid only half of what their equivalents up north had made. But it’s important to understand that Southerners felt they were gaining jobs, ones more lucrative than farmwork, making the wages at first feel sufficient even if they were comparatively scant. Meanwhile textile companies paid off politicians, who fomented anti-union sentiment through the legislature and cannily boasted about bringing jobs to the community, framing unions—which sought to improve conditions—as an enemy to the South’s competitiveness in the national labor market. Yet many of these corporations were still headquartered in the North, including Stevens’s, which was based in Massachusetts and New Jersey, far from where laborers’ grievances could be heard.

Unionization in the South was in part provoked when these Northern companies imported the “stretch-out” method, a form of “scientific management” demanding more efficiency from fewer hours and thus fewer workers. The South was being made to speed up. Speed drives Norma Rae, too. First there’s the spotty accent of Sally Field, okay in pronunciation but with a paradoxically quick drawl. It reminds me of how Mawmaw, when I was visiting home from college in New England, asked, “When’d you start talking so fast?” The film traces Norma Rae’s shifting priorities—from her asking Reuben, “Who’s got the time?” to, later, her snowed under faxes and fly sheets, proclaiming to her fellow workers, “If I got the time, you got the time!” Meanwhile, Norma Rae tells Reuben, “Things move slow around here,” by way of apology for the sluggish trickle of union membership, even though it’s the privilege of being slow the union is trying to fight for.

Before joining the union, Norma Rae, one of the most strident advocates for her fellow millhands, is bribed by her bosses with a managerial position they hope will hamstring her: spot-checking. Equipped with a billowing overshirt and clipboard, she earns an extra $1.50 an hour to walk around the factory floor watching and monitoring pace and productivity. Eventually she provokes her daddy by telling him to speed up, and his stonewalling spreads to the other workers, who subject her to the silent treatment. The foremen made a miscalculation: in a small town, community is as important to survival as hard currency.

Much of Norma Rae is taken up with the fish-out-of-water contrast between Reuben and Norma Rae, who has never met anyone Jewish before but is offhandedly curious. Jewishness is distilled to a handful of signifiers: the Metropolitan Opera, kosher hot dogs, Yiddish words like mensch and kvetch. Yet the film follows a preestablished script of how the South is depicted in Hollywood—only ever through an outsider who guides the presumed non-Southern viewer, like Virgil leading Dante down into somewhere about equally hot, through a layered land of suffering, punishment, and difference. In fact, Reuben is based on Eli Zivkovich, who had joined up with the cause as a coal miner in West Virginia. This could have been a story in which Southerners helped each other get free, but by scripting Reuben as a Northerner, the filmmakers chose not to tell it.

In the film, the two puncture each other’s illusions. Norma Rae is descended from those scrappy, no-nonsense Southern women represented in Hollywood by Scarlett O’Hara and Ruby Gentry. When Reuben, a Jewish New Yorker with a girlfriend from Harvard Law, ices Norma Rae’s nose, bloodied from that aforementioned married man, he reveals his own references: “I thought everybody down South was Ashley Wilkes.” (But Norma Rae is hardly Melanie, and Ashley never marries Scarlett.) And she witnesses a long history of Jewish leftist organizing and solidarity with the civil rights movement; at one point, Reuben preaches in a Black church, the only one willing to hold a union meeting.

The idea of solidarity among the many becomes not just a political question but a question of how to represent the South, how to represent not just one but many Southerners striving for a better life. As a mill worker, Sutton both saw herself in the movie and didn’t; liked it and didn’t. She didn’t fully trust the film or that particular union, but she knew the world was imperfect and was willing to work imperfectly for the cause. Her ambivalence was echoed in an article for the Roanoke Rapids newspaper, describing the lackluster box office for Norma Rae in Sutton’s own hometown. (Though the theater, like most local institutions, had mill bosses on its board.) In the article, one woman complains that the film portrays them as hicks; her husband agrees, but says it also feels true. What could be a better illustration of the double bind of how the South views itself?

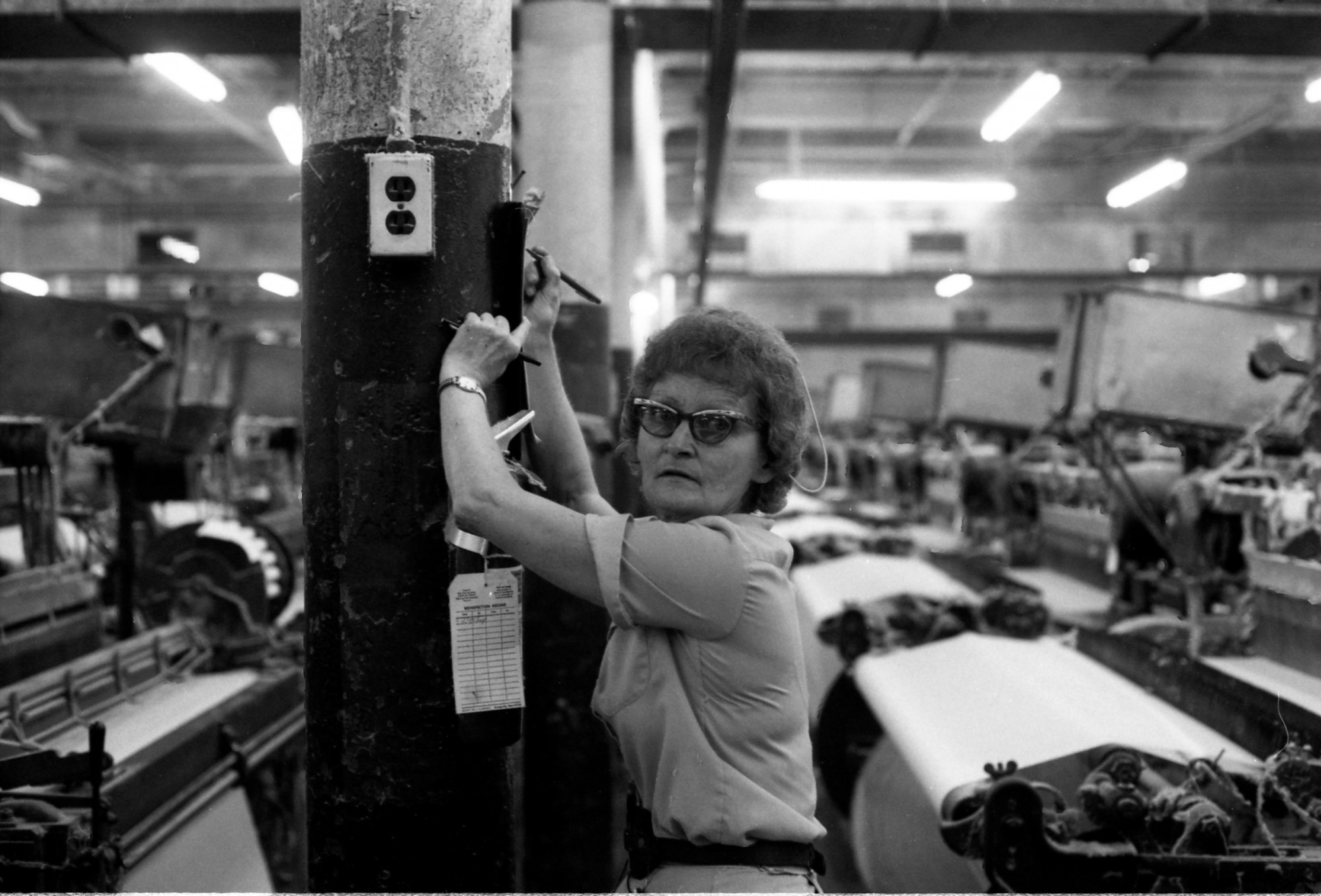

Textile plant worker, Tennessee, late 1970s. Courtesy Special Collections and Archives, Georgia State University Library

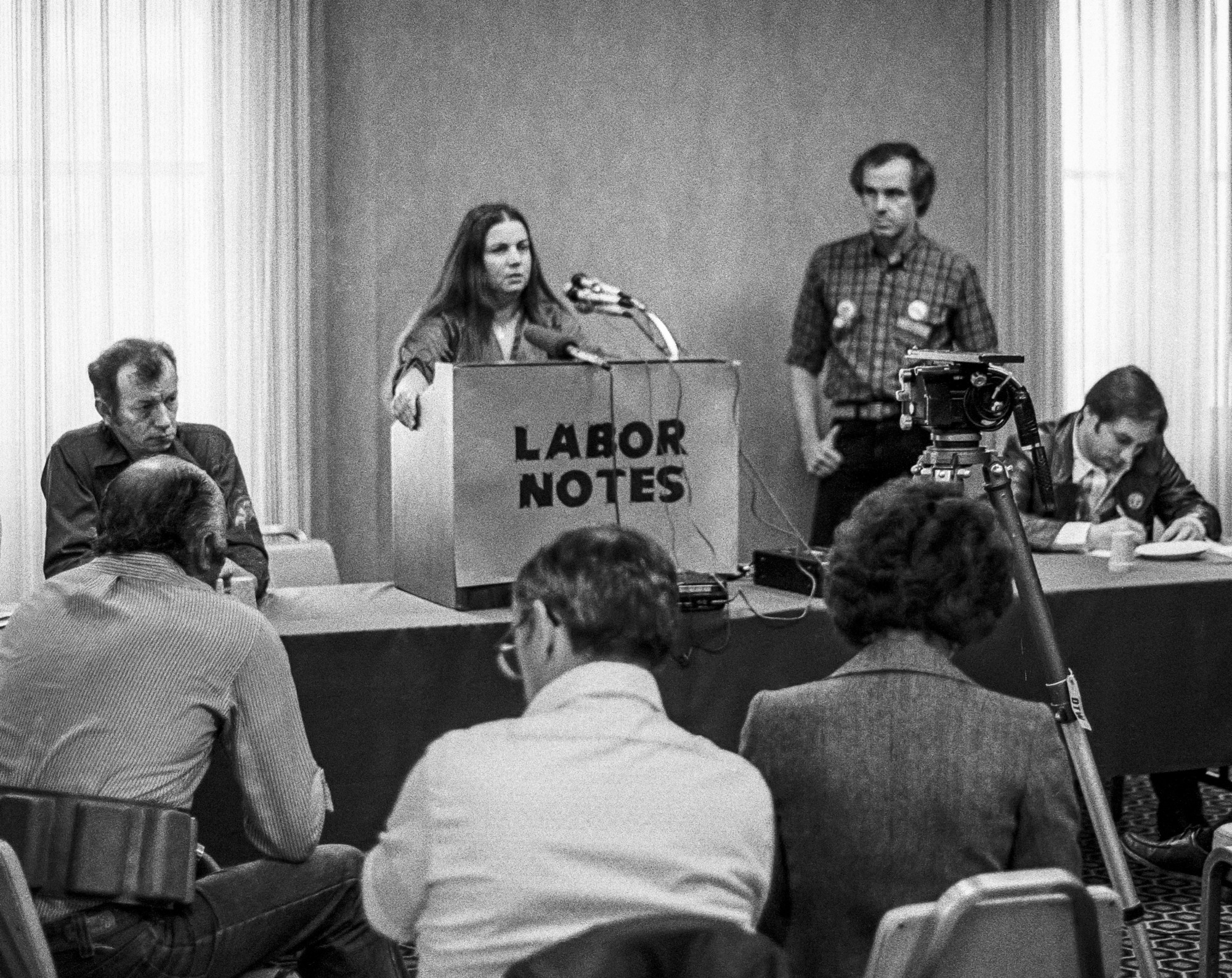

Crystal Lee Sutton addressing the first Labor Notes Conference, 1981. Photo: Courtesy Labor Notes and Jim West / jimwestphoto.com

Sutton’s and Norma Rae’s hope that unionizing would make things better in the mill for their children proved too optimistic. Textile companies, enabled by free trade acts and chasing even lower wages, have shifted to the Global South. Today, North Carolina is one of the least-unionized states in the country. Other low-paid, feminized industries—teaching and nursing—have replaced textile manufacturing as leading employers of women. In 2020, at a drive for a nurses’ union in Asheville, one of the organizers said she first learned about unions through watching Norma Rae. If industry once provided some semblance of community, and thus solidarity, then how can an atomized South knit itself together again?

Near the end of the film, Reuben asks Norma Rae what she’s going to do next: “Live!,” she replies. But for Sutton, it wasn’t so simple. She was fired from J. P. Stevens in May 1973, and the union voted for a contract in 1974. Norma Rae was released in 1979, and Sally Field won an Academy Award for Best Actress in April 1980. The union at J. P. Stevens did not secure a contract until fall 1980. The tidy arc Norma Rae presents, of millhands cheering after a successful labor vote, is belied by the final shot of Norma Rae looking small and lonely against the red-brick exterior of the mill, triumphant in her cause but wondering how she was going to feed her family. Sutton struggled to survive, finding herself mysteriously fired from job after job, trying and failing to unionize the motel where she worked as a maid.

A woman working with spools is paid by the piece or the hour or the year. Regardless, spools take her minutes. It strikes me that films unspool, suspending and giving back time. In the film’s most iconic sequence, Norma Rae, at last fired, clambers up on a table in the middle of the mill and writes UNION in bold black marker on a scrap of cardboard. She holds it up and slowly spins for a few tense moments, a gesture with no clear purpose other than its message—a word that unfurls a whole history. This is what audiences remember, the pose struck in Academy Awards montages, but its power lies in what follows: one by one, her fellow millhands switch off their machines, until for the first time the mill is quiet and stilled. In the first scene, Norma Rae’s mother is shown to have been deafened by years of loud labor; in the last, Norma Rae makes an active choice, along with the others, to stop the noise. Such silence opens a space for the workers, who otherwise must shout, to speak to each other and to listen. Maybe then the shared history of women workers wouldn’t unfurl but would unravel, fraying into enough raw material to weave a new way of being. At one point, referring not to the union but to her run-ins with men, Norma Rae says: “One of these days, I’m going to get myself all together.” That she does—but she doesn’t do it alone.