Ballads Music Credits

By Oxford American

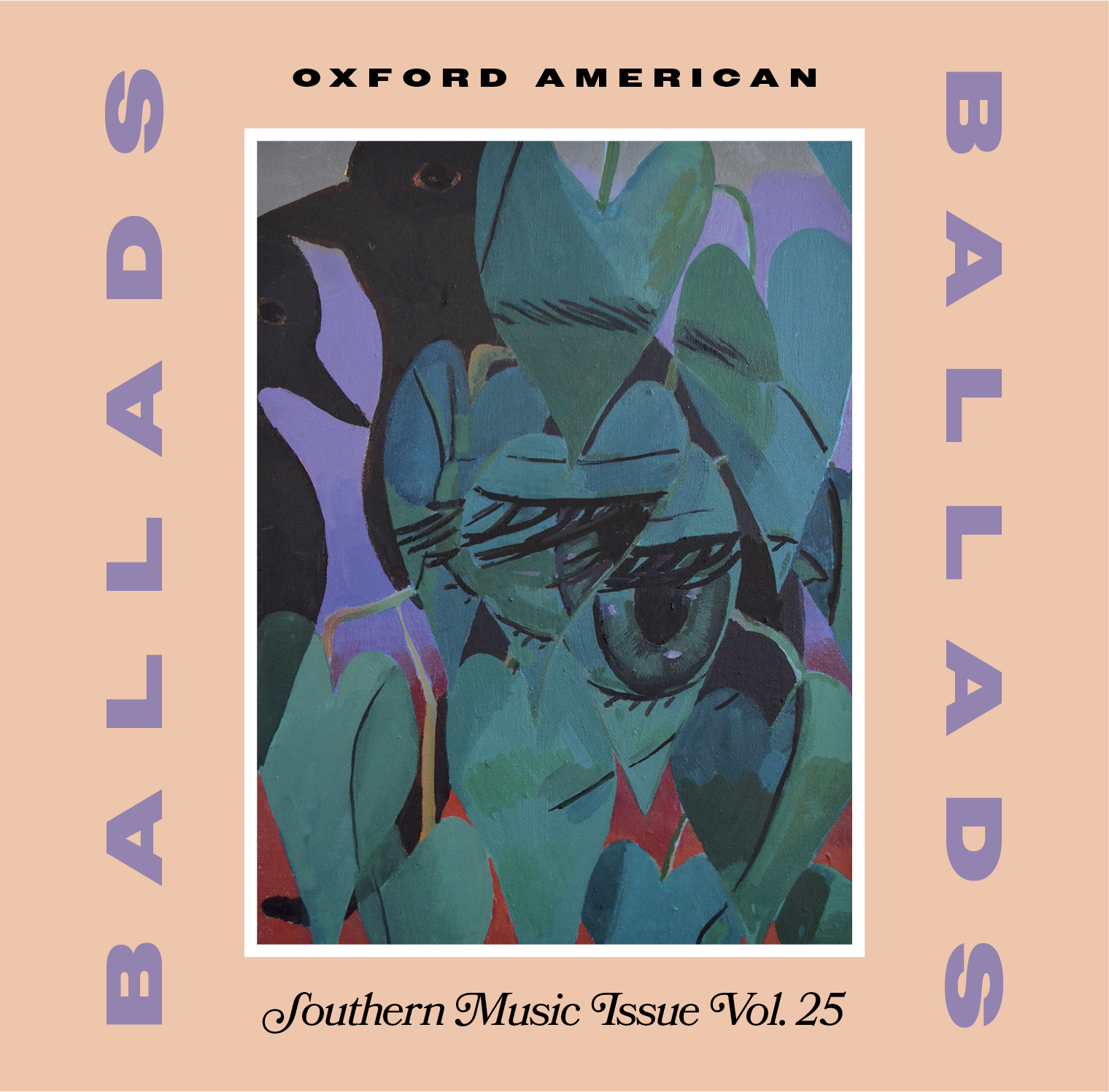

The Oxford American’s 2023 Ballads Issue sampler was compiled and produced by Patrick D. McDermott and the O.A. staff along with Andrew Rossiter (ORG Music). It was manufactured by ORG Music and mastered by Kern Haug. Its cover image is by Judy Koo, and the disc and jacket were designed by Carter/Reddy. The Oxford American believes artists and craftspeople should be paid for their labor. We are grateful to the artists and song rights holders who worked with our fee structures and, with their creativity, enrich our lives daily. We have credited them here.

WALK WITH ME, 1963

Fannie Lou Hamer

“Walk With Me” is a congregational spiritual. As such, it is designed to be malleable. In this mainstay of African American churches, the lyrics change from singer to singer, making it ballad-like in that sense, but each variant depicts a sojourner pleading to Christ. The African Methodist Episcopal Church Hymnal emphasizes the weariness of religious pilgrimages, but Fannie Lou Hamer emphasizes Christ’s ability to comfort His followers. Whereas the hymnal writes of trials, heartbreaks, and sorrows, Hamer sings of a Christ who can, whenever His believers are in need, take on many forms: In her version, He’s asked to be a friend and then a way-maker. Hamer was a leading voting rights and food justice activist from Sunflower County, Mississippi, and she often lent her singing voice as motivation during meetings and rallies. In 2015, Smithsonian Folkways Recordings rereleased Songs My Mother Taught Me, an album of field recordings that includes songs (hymns, spirituals, and a lullaby), a brief narrative, and a speech, all given by Hamer. “Walk With Me” appears in the second half, which contains recordings from a mass meeting. Hamer belts the selection out as the attendees join or give the asides so dear to Black sacred song. At the beginning, as Hamer croons the titular line, one man hollers, “That’s what we need. We need Jesus.”

Traditional/Spiritual

PERFORMED BY Fannie Lou Hamer

Courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

CIGARETTES AND COFFEE, 1966

Otis Redding

In “Cigarettes and Coffee,” an arguably overlooked track from side one of Otis Redding’s fourth studio album, the singer is so in love that he appears to be in pain. The Soul Album came out the year before Redding’s unexpected death in 1967. Redding’s vocal performance was described by one critic as “sweaty,” and “Cigarettes and Coffee” is no exception. The song begins like the dawn, with gentle blaring horns backed by a simple drum rhythm and the tinkle of a hi-hat. Redding’s voice, with its signature combination of rough and warm, croons to the woman he loves about the simple pleasure of early-morning conversation with her. Though it’s a simple domestic ballad, Redding sounds tortured by just how long it took him to find this kind of bliss: And all the good-looking girls I’ve met / They just don’t seem to fit in / Knowing it’s particularly sad, yeah. At the song’s crescendo, the backing instrumentation stays steady, but Redding is nearly crying, trying to hold on to the moment with his voice: It’s so early / so early / in the morning / so early / so early.

WRITERS: Jerry Butler, Eddie Thomas, and Jay Walker

PUBLISHING: Warner-Tamerlane Publishing Corp., Mal Williams Music Corp.

PRODUCED BY Jim Stewart, Booker T. & the MG’s, Isaac Hayes, and David Porter

PERFORMED BY Otis Redding

℗ 1966 Atlantic Recording Corp.

Courtesy of Rhino Entertainment Company, A Warner Music Group Company

OMIE WISE, 2003

Okkervil River

“Omie Wise” is the indie and folk rock band Okkervil River’s take on a murder ballad, based on the 1807 (or 1808) killing of Naomi Wise by the father of her child, Jonathan Lewis. The song is featured on their 2003 album, Down the River of Golden Dreams, a split record with singer-songwriter Julie Doiron that preceded their 2005 breakout album Black Sheep Boys. As David Ramsey’s essay “Blood Harmony” lays out, the storylines of traditional murder ballads tend to evolve, and “Omie Wise” is no exception. Over the decades, Naomi’s character has gone from an unwed mother of ill repute to a more palatable innocent. Okkervil River’s arrangement begins as a soft and simple folk tune with sparing instruments but becomes a whirlwind rock ballad in the bridge, where the narrator, in the voice of frontman Will Sheff, screams for mercy. Don’t be fooled by Sheff’s sometimes-straining voice in the song’s folksy first half—once the snare drum picks up, Sheff is truly in his element, unleashing the angry pleading of one of folk music’s oft-silenced murdered girls.

Traditional

PRODUCED BY Okkervil River

PERFORMED BY Okkervil River

Courtesy of Acuarela

AT MY MOST BEAUTIFUL, 1998

R.E.M.

Nestled within their 1998 album Up, “At My Most Beautiful” stands out in R.E.M.’s vast catalog as a ballad of piano notes and overlapping voices. The history behind its conception is as compelling as its lyrical depth. Michael Stipe, the primary storyteller behind R.E.M., shared an early chorus with friend and actor-activist Cameron Diaz. Despite the chorus resonating immediately, the quest for the perfect verse took Stipe a staggering year to complete. The song’s eventual lyrical epiphany is anchored in a line that speaks of counting eyelashes and whispering confessions of love—an intimate, captivating sentiment. This tale underscores the unpredictable nature of Stipe’s songwriting—and how a singular line can transform a good song into an unforgettable one. In Stipe’s words, it wasn’t just about crafting a “standard love song,” but about creating something with a deeply personal touch that “hooks you and pulls you in.” “At My Most Beautiful” is a love story, a journey, and a testament to the power of words.

WRITERS: Michael Stipe, Peter Buck, Mike Mills

PUBLISHING: Universal Music Publishing Group

PRODUCED BY Pat McCarthy

PERFORMED BY R.E.M.

Courtesy of Craft Recordings, a Division of Concord

THE TITANIC, 1956

Pink Anderson

Pinkney “Pink” Anderson was born in 1900 and likely would have remembered the sinking of the Titanic from his childhood in South Carolina. In the years after the 1912 disaster, the story became a global pop culture phenomenon, a slower-burning presage of the 1990s Céline Dion–fueled trend. Anderson’s version of “The Titanic,” recorded in 1950, is one of several folksongs that cropped up in the nineteen-teens to relate, comment on, and lament the tragedy. These songs, which became particularly popular with blues musicians like Anderson, are some of the most modern examples we have of the messy and meandering life cycles of folk ballads. Anderson’s lyrics give us a hint to how information about the Titanic was related orally—in one verse, he misremembers John Jacob Astor, the business magnate who was one of the Titanic’s most famous casualties, as “Jacobud Asker.” (Fellow bluesman Blind Willie Johnson, in his version of “God Moves on the Water” from 1929, similarly misremembers Captain E. J. Smith as “A. G. Smith.”) Anderson combines his localized version of the Titanic story with sparkling, up-tempo guitar that transforms the tragedy into a dance track. The insistent, questioning chorus—Wasn’t it sad when the great ship went down? Wasn’t it sad when the great ship went down?—catches and sticks in the ear and has hooked generations of listeners.

Traditional

PERFORMED BY Pink Anderson

Courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

HOW DO I LIVE, 1997

LeAnn Rimes

At the 1998 Grammys, fifteen-year-old LeAnn Rimes performed “How Do I Live,” a ballad written by Diane Warren and brimming with—to borrow a phrase from Lauren Du Graf’s feature from this issue—“codependent excess.” A few minutes later, Trisha Yearwood beat out Rimes in the Best Country Female Vocal Performance category for her version of “How Do I Live,” which was likely recognized by country voters as a more classic-sounding interpretation from a genre veteran; it was the first time in the award show’s history that two artists were nominated in the same category for the same song. But even though Yearwood’s version took home the Grammy and was preferred for the soundtrack of the Nicolas Cage action blockbuster Con Air, Rimes’s version—soaring and soulful, with falsetto flourishes that hint at her yodeling bona fides—spent sixty-nine weeks on the Billboard Hot 100 and is remembered fondly as one the ’90s premier schmaltz sing-alongs. (It spent some of those weeks directly competing with Usher’s “Nice & Slow,” further evidence of ballads’ omnipresence at the turn of the millennium.) Some reports suggested that the movie studio passed because they felt Rimes was too young to convincingly express the song’s grownup-grade yearning (a claim Rimes told Texas Monthly the film executives denied)—and yet, who understands romantic melodrama and unchecked devotion better than a teenager?

WRITER: Diane Warren

PUBLISHING: Real Songs (ASCAP)

PRODUCED BY Chuck Howard, Wilbur C. Rimes

PERFORMED BY LeAnn Rimes

Courtesy of Curb Records

IT HAD TO BE YOU, 1975

Milt Hinton and Friends

Milt Hinton—better known as “The Judge,” for his legendary timekeeping—was the heartbeat of 1950s jazz, laying down bass line rhythms for the likes of Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie, Count Basie, and Cab Calloway. Despite being one of the most recorded bassists in history, few recordings were released under Hinton’s own name. “It Had to Be You” is featured on Here Swings The Judge, a rare LP released with Hinton at the helm. Alongside Jon Faddis’s mute work on trumpet and John Bunch’s tickling piano, Hinton’s bassline shines through in their arrangement of the American songbook classic. In 1919, when Milt Hinton was nine, he and his family moved from Vicksburg, Mississippi, to Chicago, away from the oppression and lack of opportunity facing many Southern Black families. Immersed in Chicago’s church choirs, Hinton began piano lessons and later enrolled in the National Black Music Association and Wendell Phillips High School, gaining a rigorous music education and catapulting himself into the jazz world.

WRITERS: Isham Jones and Gus Kahn

PUBLISHER: Famous Door Records

PRODUCED BY Harry Lim

PERFORMED BY Milt Hinton

Courtesy of GHB Jazz Foundation

ABILENE, 2022

Plains

Not all country music is about heartbreak, but country music does heartbreak pretty well. The music of Plains—the collaborative project featuring Alabama-raised Katie Crutchfield (aka Waxahatchee) and Texas-born singer-songwriter Jess Williamson—tackles the heartbreak that comes with choosing yourself over the relationship, the place, the vibe, that is not working for you. Their twangy harmonies reveal the sadness and the hope that comes with major life change: I’da stayed there forever, ’til death do us part / Texas in my rearview, plains in my heart. Crutchfield has said that “Abilene,” written by Williamson, was the song that “solidified” the duo’s debut album, and there’s no doubt that this downtempo, three-chord ballad earns its spot among the best country collaborations, calling to mind Trio, the Judds, and the Chicks.

WRITER: Jess Williamson

PUBLISHING: Orgasmic Bliss (BMI) c/o Covertly Canadian Publishing

PRODUCED BY Brad Cook

PERFORMED BY Plains

Courtesy of Epitaph Records

BE REAL BLACK FOR ME, 1972

Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway

In 1969, Billboard changed the r&b chart’s name to “Best Selling Soul Singles,” calling the new genre a kind of “musical Americana” that drew on gospel, jazz, pop, and the blues. The sound was urgent, crackling with vitality and truth-telling. It reflected the vicissitudes of the decade, when victories like the Voting Rights Act had been won, but had also been met with violent retaliation. Weary leaders urged an inward turn. The word “soul” became shorthand for Black authenticity and pride. Before long, there were “soul brothers” and “soul sisters,” “soul food” and Soul Train.

In the fall of 1971, former Howard University classmates Donny Hathaway and Roberta Flack collaborated on their first of two albums of duets. Both had come from smaller Southern towns to Washington, D.C., and had been child prodigies. Both played piano with gospel and classical training. Flack described Hathaway as “very shy, very self-conscious about his weight”; she said that when they were starting in the music business, they both were. Their albums together vibrate with the tender intimacy of being seen.

On “Be Real Black for Me,” the two trade lines of devotion, beginning with Hathaway, who describes the moment: “Our time, short and precious.” He means shared time, with the beloved, but also, perhaps his time—our time—on the planet. He loves the person in spite of what everyone else says is wrong: their luscious lips and crinkly hair. Black, formerly an insult spewed on hateful tongues, became, on Donny’s and Roberta’s, something lovely, with value. In my head I’m only half together, the two sing in unison, harmonies lilting over a soaring bridge. I fall short of this love, they seem to say, and so do you. But we need each other more than all the earth’s riches. “There is something about the way love flows between the two,” Ashawnta Jackson writes in this issue.

WRITERS: Roberta Flack, Donny Hathaway, Charles Mann

PUBLISHING: WC Music Corp. / Universal Music Publishing / Microhits Music Corp.

PRODUCED BY Arif Mardin, Joel Dorn

PERFORMED BY Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway

Courtesy of Rhino Records, A Warner Music Group Company

THE DAY IS PAST AND GONE, 1964

Buna Hicks

“They have new songs and they’re right pretty—some of them is—but I still hold to the old songs,” Buna Hicks says in Tom Burton’s book Some Ballad Folks. As Justin Taylor explains in this issue, some of the songs Hicks and her Beech Mountain, North Carolina, contemporaries sang were very old indeed, with roots in Renaissance poetry. “The Day is Past and Gone” is a relative neologism by those standards—its lyrics were written in 1792 by John Leland, a Baptist minister from Massachusetts. But by the time Hicks recorded her version of the hymn for Smithsonian Folkways in the early 1960s, it was thoroughly integrated into her own musical tradition. The liner notes for The Traditional Music of Beech Mountain, North Carolina Volume 1, on which the recording initially appeared, note that the hymn was sung harmonized in the local church. Hicks sings it solo, to an austere, knobbly tune that seems to summarize the dense chords of “Idumea,” the shape-note melody written by Ananias Davisson in the nineteenth century. Her voice renders the lyrics, already dire, into something apocalyptic, adding in time-worn grace notes and the “yips” that “Orphan Girl” author Melanie McGee Bianchi in this issue still hears in the ballad singing of western North Carolina today.

WRITER: John Leland

PERFORMED BY Buna Hicks

Courtesy of Smithsonian Folkways Recordings

HAWK FOR THE DOVE, 2022

Amanda Shires

From Amanda Shires’s seventh solo album Take It Like a Man, “Hawk for the Dove”’ is an Americana power ballad about a woman who knows what she wants. A Nashville-based singer, songwriter, and fiddle player, Shires—also known as one-fourth of the country music supergroup the Highwomen—says of “Hawk for the Dove” that, “I want people to know that it’s okay to be a forty-year-old woman and be more than just a character in somebody else’s life.” Written by Shires and Lawrence Rothman, the song explores “the emotions that turn prey into predator.” Shires, who was born in Lubbock, Texas, has Southern roots that come out in her music. From her tremulous voice to her skilled fiddle, the markers of her West Texas upbringing are evident across her discography, including her most recent release, Loving You with the late Bobbie Nelson, featuring vocals from Bobbie’s brother, Willie Nelson.

WRITERS: Lawrence Rothman and Amanda Shires

PUBLISHING: Little Lambs Eat Ivy Music, BMI

PRODUCED BY Lawrence Rothman

PERFORMED BY Amanda Shires

Courtesy of ATO Records

THINK OF LAURA, 1983

Christopher Cross

Laura Carter was an eighteen-year-old college student who was killed by a stray bullet in Columbus, Ohio, while sitting in the backseat of her father’s car. The Texas-born singer Christopher Cross was dating her roommate, and he wrote “Think of Laura” as a tribute. It’s a tender tragedy ballad, with somber chords and unfussy elegiac poetry: “Hey Laura, where are you now? / Are you far away from here? / I don’t think so / I think you’re here / Taking our tears away.” It’s an unsubtle yet effective tearjerker, thanks in large part to the Grammy- and Oscar-winning songwriter’s trademark serene timbre, which is imbued here with a genuine-feeling melancholia. True to the spirit of the ballad tradition, Boyz II Men would later reimagine the track as “Think of Aaliyah”—in memory of the late, great r&b singer who died in a plane crash in 2001.

WRITER: Christopher Cross

PUBLISHING: Get Ur Seek On (ASCAP) c/o Universal Music Publishing

PRODUCED BY Michael Omartian

PERFORMED BY Christopher Cross

Courtesy of Seeker Music

THE CARRIER LINE, 1942

Sid Hemphill

Known as a talented instrumentalist (of the fife, panpipes, fiddle, mandolin, drums, and more) and instrument maker, Sid Hemphill, a blind man from Mississippi whose father was at one time enslaved, was also a prolific balladeer. His ability to come up with lyrics on request built him a reputation across his region; as explained in Jim O’Neal’s essay about Hemphill from this issue, locals would approach him to commission songs about events worth memorializing. Songs like “The Carrier Line”—a ballad detailing the wreck on the Sardis & Delta Railroad owned by Sardis lumber baron Robert Carrier—exemplify his uncanny knack for turning true stories into lively, lasting music. It also exists in conversation with other train wreck ballads, like “Engine One-Forty-Three” and “The Ballad of Casey Jones.” Alan Lomax and Lewis Jones sought out Hemphill in 1942 as part of a historic project, supported by Fisk University and the Library of Congress, to create an archive of songs from the South. When Lomax joined him at a summer picnic, Hemphill became the first person in Mississippi to record fife and drum music with his band.

WRITER: Sid Hemphill

PUBLISHING: Mississippi Records

PRODUCED BY Alan Lomax

PERFORMED BY Sid Hemphill, Alec Askew, Lucius Smith, and Will Head

Courtesy of Mississippi Records

DEAD HORSES, 2022

The Local Honeys

“Dead Horses” appears on the self-titled album by the Local Honeys, a folk bluegrass duo based in Kentucky. The song is, obviously, about dead horses: The narrator, voiced by Linda Jean Stokley, recounts a buckskin pony that mourns beside her dead mother. The narrator mourns with the pony, as she “never got used to watching horses die.” The song is intimate, with Stokley’s lead vocals and Montana Hobbs’s cascading fiddle, and offers a bittersweet view of rural, Appalachian life. Here, animals and humans are connected in both love and grief. Madeline Weinfield writes in this issue of a similar connection to the horses of her own youth, the memory of which, “like a first love…burns sometimes still.”

WRITER: Linda Jean Stokley

PUBLISHING: Gerle Travis Publishing, BMI

PRODUCED BY Jesse Wells, Linda Jean Stokley, and Montana Hobbs

PERFORMED BY The Local Honeys

Courtesy of The Local Honeys

PA’LANTE, 2017

Hurray for the Riff Raff

In Clarissa Fragoso Pinheiro’s essay on Chilean folk artist Violeta Parra, she writes that the artist never had the chance to “witness the profound impact her songs would have on social movements in Latin America, particularly the Nueva Canción, a movement of politically engaged music inspired by folk traditions.” We can trace a line from this movement in the ’60s and ’70s to the work of New Orleans–based Alynda Mariposa Segarra, aka Hurray for the Riff Raff. Segarra has said that this song was a means of connecting with both their Puerto Rican heritage and activists of the past who have challenged the status quo, especially the status quo that excludes queer people and people of color. In many ways, the song’s simple melody and straightforward lyrics of protest hearken to the revolutionary work of Violeta Parra. Though the lyrics speak more directly to our contemporary world, “Pa’lante” feels kindred to “Gracias a la vida,” with its yearning for a simplicity and freedom of life that so many struggle to experience. “¡Pa’lante!” literally urges listeners “onwards” and “forward”; they sing To all who had to survive, I say, ¡Pa’lante! / To my brothers, and my sisters, I say, ¡Pa’lante!

WRITER: Alynda Segarra

PUBLISHING: Mariposa Gang Publishing (BMI) administered by Domino Publishing Company of America Inc. (BMI)

PRODUCED BY Paul Butler

PERFORMED BY Hurray for the Riff Raff

Courtesy of ATO Records

THE GLORY OF LOVE, 1965

George Lewis & the Barry Martyn Band

First, get that Peter Cetera song “Glory of Love” from the Karate Kid II soundtrack out of your head. “The Glory of Love,” written by Billy Hill in 1936, is one of the twentieth century’s most durable love songs and has appeared on soundtracks from Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner to Beaches. Composed by Hill during the Great Depression, at first listen, its lyrics feel like jaunty platitudes: You’ve got to give a little / take a little / let your poor heart break a little / That’s the story of / That’s the glory of love. But when you consider that the song was written during one of the nation’s longest economic downturns and you consider how difficult it must have been for most people to survive, let alone thrive, the lyrics gather greater meaning: As long as there are two of us / We’ve got the world and all its charms / And when the world is through with us / We’ve got each other’s arms. This 1965 instrumental version by New Orleans jazz clarinetist George Lewis and the Barry Martyn Band, swings with joy, and feels like the stroll of two lovers who’ve just had a lucky break and are on their way to celebrate, even with the knowledge that the win may be fleeting. For now, they will seize the moment.

WRITER: Billy Hill

PRODUCED BY Barry Martyn

PERFORMED BY George Lewis and the Barry Martyn Band

Courtesy of GHB Jazz Foundation

LIAR, 2023

Paramore

Maggie Boyd Hare writes in this issue that when pop punk outfit Paramore wrote in the 2000s about love, “it was dark, cynical, and it went hard.” While much has changed for the band since the release of their 2009 hit ballad “The Only Exception,” they’re still unafraid to confront love’s sharper edges. Like “The Only Exception,” “Liar” is a quieter, more reflective moment in the band’s catalog—but it’s also easy to hear the fourteen years of ballad-writing evolution between the two tracks. Rather than what Hare calls the “worship band strum pattern” of “Only Exception,” “Liar” opens with a stuttering guitar arpeggio, a melody like falling water drops. Lead singer Hayley Williams, rightly known for her powerhouse vocals, forgoes the belting in favor of airy high notes that showcase her bell-like timbre and pinpoint intonation. Meanwhile, the song’s lyrics echo the almost transgressive vulnerability Hare finds in “The Only Exception,” releasing both singer and listener to fully feel their messy, inexplicable, inelegant emotions: Love is not an easy thing to admit, Williams sings, but I’m not ashamed of it.

WRITERS: Hayley Williams, Taylor York, and Zac Farro

PUBLISHING: WC Music Corp., Hunterboro Music, Zac The Wolf Music, But Father, I Just Want To Sing Music

PRODUCED BY Carlos de la Garza

PERFORMED BY Paramore

℗ 2022 Atlantic Recording Group LLC

Courtesy of Atlantic Recording Corporation

The Final Gift, 2023

Dom Flemons

The ballad is a form we love because it refuses categorization. Is it a poem? Is it a song? Is it a story? Is it a lyric? Yes, and. From Chaucer to B. B. King, Langston Hughes to Lydia Mendoza, Westerners have bent the millennium to carry this ancient form forward to teach, grieve, and heal. For this issue, we commissioned a new traditional ballad from Dom Flemons, Grammy-winning “American Songster” and a bearer of this country’s rural music inheritance. “The Final Gift” is presented here just as it is: a poem and a song, a story and a lyric, a work of art that is both nascent and old. Written in the formal style, with an iambic pulse and hard rhyme patterns, “The Final Gift” reminds us of true love’s most common story: true love, missed. Marie would walk the sea to meet her rambling beloved, but when she finds him he is already gone to regret’s many deaths. It’s a heartbreaker. Flemons seems to ask us, is true love only ever valued after it is done? Can we still awaken to its power in our lives, before it is too late? As if to hope for a different ending, this poem-song edits itself as it sings, with Flemons making slight adjustments in the parallel refrains, his raw voice breaking across the tide of notes. A work of living tradition, “The Final Gift” draws from murder ballads and dying verses, only this execution is brought by the wicked hand of missed chance. True love’s most common story—made new, by honoring its age.

WRITER: Dom Flemons

PUBLISHING: American Songster Music, ASCAP

PERFORMED BY Dom Flemons

Courtesy of Dom Flemons