Hearing Aids

A Short Story

By Clyde Edgerton

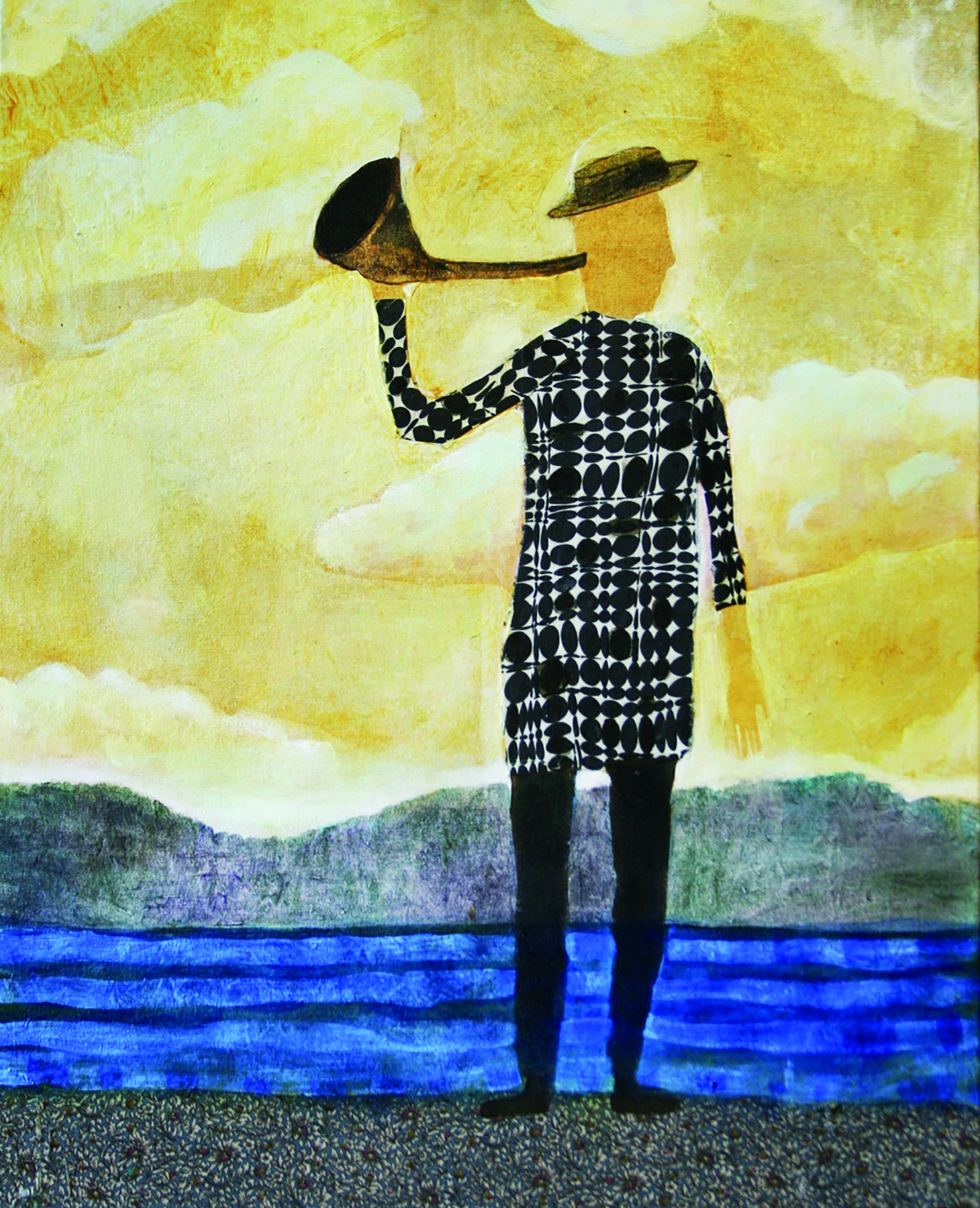

The Hearing Trumpet, 2015, mixed media and textiles on canvas, by Donald Saaf. Courtesy the Clark Gallery

It occurred to Forrest that he needed to think about who he should leave his hearing aids to. His first thought was his brother who had some cheap ones. But no, not him. He was thinking this while standing at the commode urinating. While his pee was hitting the water, making those sounds like a slow-running kitchen faucet into a pan of water, he sometimes liked to isolate one of the sounds and make a word out of it. Well, no. He didn’t exactly like to do that. It was just something to do while standing there.

He listened… “prosecute.” Then… “scrambled.” He finished, flushed the commode.

He thought about Van, his neighbor. He could leave the hearing aids to Van. Last summer, out by the driveway, Van had said he couldn’t hear shit. And then about two weeks ago, when they stood a short way down the road watching a bulldozer work, he said the same thing again.

If he left the hearing aids to one of his own children that wouldn’t work because by the time they were needed they would be extinct, like a DVD player. He remembered the old man who used to sit in the lobby of the courthouse holding what looked like a hollow elk horn in his lap. He’d pull it up to his ear when somebody talked to him, and on more than one occasion Forrest’s mother had said, “Go ahead over there, son, and say something to him. Say ‘How are you today, Mr. Umstead?’” His mother had gotten him to step up to a lot of things that he was kind of undecided about. She’d pushed him into piano, and art lessons, and theater. None of it stuck. He’d joined the army, served thirty years, and then retired. His wives had encouraged him to get involved in several hobby-things that didn’t quite work. All that—gone.

He thought now about how Mr. Umstead, the man with the ear horn, must have, as a boy, seen old men, maybe old women, sitting somewhere with an ear horn, and how then those people, as children, had seen old people with ear horns…and so on for no telling how many generations back—without change. Just plain and simple steady human stuff through time. He thought about his iPhone and the misery that had brought on, his hearing aids, his prostate, his dick, his elbow, his eyesight—about how his handwriting had started getting shaky, and then shakier, and how he’d clearly noticed the same thing when it happened with his mother, his father, and finally Frances. He wondered how many of those motherfuckers with ear horns in the last thousand years had been happier than he’d been. How many had died happy? Who died happy? Happy in general. How many had stayed happy all along? Had had somebody they were intimate with and laughed their asses off with right up to the end. If Frances were alive, he might mention that to her in front of the fireplace. If his army buddy, Talmadge Cochran, were alive, Forrest could call him and say, “Talmadge, you want my hearing aids?” They’d laugh about it.

By now he was in the backyard. He sat down in the outdoor lounge chair facing the morning sun, and he felt the warmth on his face and knees and chest. The morning was cool. An intense wave of sadness came upon him, then ached in his chest.

He couldn’t get the hearing aids out of his mind. It occurred to him that there should be a long list of people to leave them to, but nobody much was coming to mind. And who would clean them and prepare them for the gift box? Maybe he should think of an organization, an organization that would give them away. He thought of Goodwill—some old lady shopping in there and looking into the glass case up front and saying, “Is that a pair of hearing aids?” And there they’d be, light gray, beside the necklaces and rings and earrings—there they’d be, all cleaned up, each with the little plastic string that you’re not supposed to see, and the tiny speaker the size of a match head that goes into your ear canal. And the saleswoman says, “Oh, they’re special. I think they retail for several thousand dollars and they are…what? Two hundred?” She and the old woman look into the case but the price tag has been turned over, so she pulls out her key ring and opens the glass case and turns over the price tag, and says, “Two hundred dollars. Yep, two hundred dollars.”

Why isn’t there a hearing aid bank? he thought. Think of how many perfectly usable hearing aids become available in funeral homes, for crying out loud. And think about what you go home to if you’ve got a job at Goodwill. Thank God he avoided that.

Forrest started to get up but sat back. He thought about how in the last year everything was going downhill. That song: “I’m on the Downside of the Downswing.” He had noticed that even with the hearing aids in, he was hearing less and less well. But they were very fine ones, adjustable in sensible ways.

Think of how many perfectly usable hearing aids become available in funeral homes, for crying out loud.

He heard the eleven A.M. train whistle. That was the slow train. The fast train was usually somewhere between two and two-thirty. The slow-moving morning train would have all these clank and scrape sounds, and the fast train would have a kind of simple, very loud rumble-roar. It hauled ass. That’s the one he liked to watch from up close. He wondered how those sounds compared with the ones from 1850 or whenever that final rail spike had been driven, in the middle of the country. And how many people on that very first cross-country passenger train ride had ear horns in their laps? He wondered if some people back then used ear horns that had been in their families for hundreds of years. Surely, they got passed down. Why didn’t you see them in antique stores?

He thought about all those hearing aids that were the size of a pack of cigarettes and fit into a shirt pocket and had a wire running up to one ear. Back in the fifties. He didn’t recall ever seeing a woman with one. They must have had them.

His helper, Sarah, would be by at noon, with his lunch and some paperwork to leave off. She was very faithful and a good worker. Finally… He had had to let three others go. He went back inside to wait for her.

He remembered that time he was getting an MRI for his prostate cancer—to see if, or how much, the cancer had advanced—and he thought of the sounds coming from the machine, a machine that had swallowed him. The sounds were unlike any other sounds. A high-pitched sound would be repeated for maybe fifteen seconds and then it would switch to a loud popping or some other sound, but the next sound might sound like two words: go man go man go man go man go man, over and over.

The doorbell rang. Forrest greeted Sarah. They walked into the kitchen and she set his lunch on the table and beside it placed the papers she had been working on. She asked him if he felt okay, and he said, “Fine.”

Then he said, “Let me ask you an odd question, Sarah. Is there anybody in your family who is hard of hearing and might be interested in a pair of hearing aids?”

He got Sarah to write down her mother’s name on his notepad and when Sarah left he wrote out a little codicil and paperclipped it onto his will—where there were several others clipped on. He’d told his children he’d be doing this from time to time. His lawyer had approved.

Suddenly he was very nervous and shaking some. He walked to the bathroom, took off his hearing aids, and placed them beside the sink. He looked at himself in the mirror. He saw and felt the great wide valley, the great wide, dark valley between him and Mr. Umstead, who was sitting way over there beyond the valley, on that hill. The valley had grown so deep and wide and was crammed so full of so many things, all those things that his mother saw for the first time, airplanes and automobiles, telephone wires, electricity, jets, wars, and wars, and his war, and marriages, and children. The valley had been expanding as if alive. If he could count on somebody to love him. If he gave a shit anymore for making love. If there were somebody to help him have experiences that he was kind of undecided about. If he could go back, or if he could only move forward a little bit.

Out back, he walked past the chair he’d been sitting in, and went to meet the train.