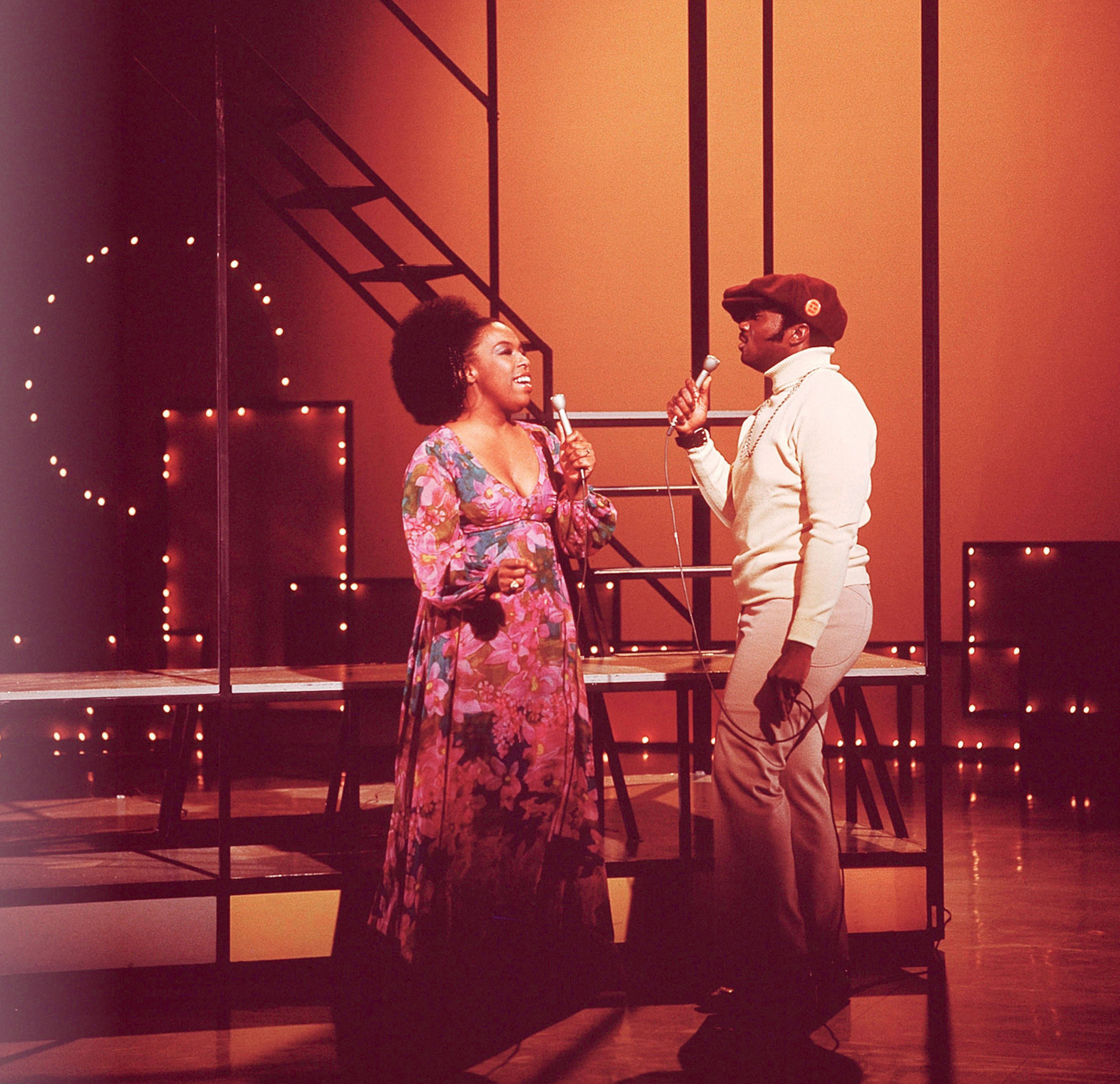

Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway performing on BBC TV, 1973 © Michael Putland/Getty Images.

Radical Light

The cosmic collision of Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway

By Ashawnta Jackson

There’s something called a kilonova, when two fast-moving stars collide with one another. It creates a brilliant light, brighter than anything each body alone could create. Physicist Albert Sneppen called it a perfect explosion because of the “simplicity of the shape” and its “physical significance.” And maybe that’s what made 1972’s Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway so special. It was something so simple, in its way: two former Howard University students finding the musical force of each other impossible to resist, colliding to create something so bright, so beautiful, so heavy in its significance, that even now, some fifty years later, all we can do is marvel at its weight and let its brightness cover us.

There is something cosmic about this pairing. The way their voices slide, tease, intertwine. Playing off each other in ways that feel both sharply studied and effortless. There is something about the way love flows between the two, letting it touch everyone in its presence. This wasn’t just an album for them, this was an album for us. “Black artists have a total sound and culture that sets their work apart from others,” Hathaway told an interviewer in 1972. And that sound comes through track by track. From the ache set upbeat soul of “Where is the Love”; to the elegiac “For All We Know,” where love is sensual and sacred; to “Mood,” a gorgeous, unclassifiable seven-minute meditation where the classical influences shimmer through, her acoustic piano and his electric one speaking to each other when their voices do not; to “Be Real Black for Me,” a musical ode to the idea that Black is Beautiful and to the love found in celebrating that beauty.

These celestial beings were always destined to meet.

While Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway were both still students at Howard, they dreamt of musical success. Neither knew what that might look like, but for Hathaway, who dropped out in 1967, it didn’t look like academia. After leaving Howard, he had first headed to Tampa, Florida, and later moved to Chicago to become a writer and arranger for Curtis Mayfield’s Curtom Records. He crafted an impressive résumé during this time. He arranged the Impressions’ poignant “Choice of Colors”; played piano on the Motown-esque “Girls Are Out to Get You” by the Fascinations, released through Mayfield Records, a Curtom predecessor; and wrote “Zambezi,” a lush, dreamy funk for the Soulful Strings.

Before leaving D.C., he’d been playing piano and singing in a church in the city, but it wasn’t paying his bills. “I considered how I really needed to earn some money to continue my studies,” he told Blues & Soul in 1972. “I joined a trio, the Ric Powell Trio, and we played the local supper clubs and cocktail lounges.” This was how he first crossed paths with Flack. “I knew Roberta way back when I was with the trio,” Hathaway said. Flack’s then husband, bassist Steve Novosel, was one of the trio’s members. It was Novosel who first suggested that the two might work well together. Hathaway recalls their partnership in such a matter-of-fact way that it’s almost easy to forget the beauty this pairing created. “Roberta was about to be presented to Atlantic,” Hathaway told Blues & Soul. “And Steve suggested I might do some songs and arrangements for her. Naturally, I was overjoyed and so I went down to Washington and presented my songs.”

Flack had stayed at Howard, and after graduation taught school in rural North Carolina, but she frequented D.C. often to play at local clubs. She eventually found a teaching job there and moved to the city full-time. Two of Hathaway’s songs appeared on Flack’s first album, 1969’s First Take. One, a sweeping ballad about a (at best) May-December romance and the other the absolute perfection of “Tryin’ Times,” a funk-jazz sliding soul song that manages to convey the hurt of injustice and encapsulate an ever-shifting landscape of political violence, protests, and a world that tries the soul a little more each day. The album was a critical and commercial success, hitting number one on both the Billboard pop and r&b charts, and number three on the jazz chart.

Roberta Flack and Donny Hathaway, 1972 © Jim Marshall Photography LLC.

By 1970, Hathaway was moving from the background with his own release, Everything Is Everything, which, like Flack’s album, was released on Atlantic. His debut reached a respectable number thirty-three on the r&b chart and number seventy-three on the Top 200 Albums chart, and its follow-up the next year, a self-titled album, went to number six on r&b and eighty-nine on albums. He wasn’t as successful as everyone—the label, fellow musicians, music media—thought he could and should be.

The idea of a duet album was one that neither one had to be talked into, Emily J. Lordi explains in her book on Hathaway’s 1972 album, Donny Hathaway Live. They knew each other well, respected each other’s work, and their previous work “reveal[ed] these two artists’ musical compatibility.” It also represented a step onto a larger stage for Hathaway. Pairing him with Flack was as much a business decision as an artistic one. The musical match was the brainchild of Atlantic Records executive Jerry Wexler, and as Hathaway told Blues & Soul, “He thought that Roberta and I could come up with some good ideas together because he knew how well we had worked.”

The album came into being in a time of revolution. There were the loud, visible, public kinds—the marches and rallies, the sit-ins and boycotts. But revolution can also happen in the places we don’t expect. There is a revolution in the sway of the hips, in holding each other closely, in a syncopated rhythm helping us find our voices as we chant “I’m Black and I’m proud,” in the freedom that comes from a body in possession of itself. Black music provided the soundtrack, but it was also its own weapon in the fight. As Phyl Garland, Ebony editor and author of the landmark 1969 book The Sound of Soul, explains, Black music contains “a defiance and rejection of things as they were.”

Concert Flier, Sunday, September 16, 1981. Courtesy the Maynard Jackson Mayoral Administrative Records at the Atlanta University Center Robert W. Woodruff Library.

Music helped us find our way to freedom, a spiritual guiding feet northward. It helped build churches, powerful spaces of resistance where music helped steel the soul and the body for the fight ahead. And in 1960s and ’70s America, Black music was transforming not just the way others saw us but the way we saw ourselves. For Flack, her music represented not just a display of her talent but her contribution to this ever-growing fight for rights. “As strongly as I believe in the black struggle,” Flack once told an interviewer, “I know that my best bet is to express this through music.” And for Hathaway, Black music was at the center of American musical culture, and like it was for Flack, his way to contribute. His songs displayed this passion, including “The Ghetto” (“I felt it was a song that all Black people could relate to,” Hathaway wrote in the liner notes of his 1973 album Extension of a Man) and “Someday We’ll All Be Free,” a song that represents a promise, a devotion, an eternal hope.

Their music, together and separately, was a defiance and a rejection, but it was also an assertion: We see you. They saw the shifting hues of Blackness in its beautiful arrays. They saw that there was value, and spirit, and love in all of it. And then, as now, Black love was a radical act. Their album of duets, each track, each in its own way, explored the fragility, the contentedness, the softness, the hurt, the complexity, and the simplicity of love. This wasn’t just a musical action, it was a political one.

But maybe the one track that is most defiant, most steadfast in its refusal to accept things as they are, is “Be Real Black for Me,” a track written by Flack, Hathaway, and songwriter Charles Mann. It’s an album track, deep on the first side. Not so much buried as discoverable, a treasure waiting for you. The song is a celebration:

Your hair, soft and crinkly

Your body, strong and stately

Not only does it celebrate what Blackness is, it celebrates what it is not. You don’t have to wear false charms, Hathaway croons. You don’t have to search and roam, Flack responds. It’s not just that each is safe with one another. It’s a rejection of the expectations society has placed on this love, and a reflection on the ethos of revolutionary Black art.

In a 1971 interview with Ebony, Flack said, “I like to say that two preachers came from Black Mountain [North Carolina]. Billy Graham and I. He’s preaching in his way and I’m preaching my way.” And for me, a failed church girl who, for a part of my life, was made to sit on worn pews in an effort to save my soul, I understand. Religion, at least in the way that my parents hoped for, didn’t stick. It wasn’t the words that kept echoing in my head, it was the music. I love the way a hymn can make me feel, like a soft breeze on warm skin. A whispered affirmation. And once I realized that music—any kind—can feel holy and sacred, I knew I’d found my religion. I found it in notes and hooks and soulful choruses. I found it in a voice bending a note, sustaining it, caressing it. Preach, Roberta, preach. Give your sermon of star-crossed lovers, hopeless romantics, and joyful noises. I believe. “I think music does save you,” she told Essence magazine in 1989. “[The arts] can save your life if you’re able to reach out and touch them and hold on.”

We may not all be able to hold on, but when Flack’s voice finally met Hathaway’s, these two stellar beings, moving faster and faster toward each other, it felt like the universe was becoming something understandable, something graspable. “I’ve never stopped being amazed at Roberta,” Hathaway told Blues & Soul. And in this album, in “Be Real Black for Me,” we can feel that amazement, and a shared wonder of being in each other’s presence, in each other’s creation.

Two stars hurtling toward one another, toward perfection. And for one electrifying moment, the collision was blinding.