Project Pat performing at the Beale Street Music Festival, May 2022 © Patrick Lantrip/The Daily Memphian

Smile with the Sad

The hopeful melancholy of Project Pat’s “Life We Live”

By Ben Dandridge-Lemco

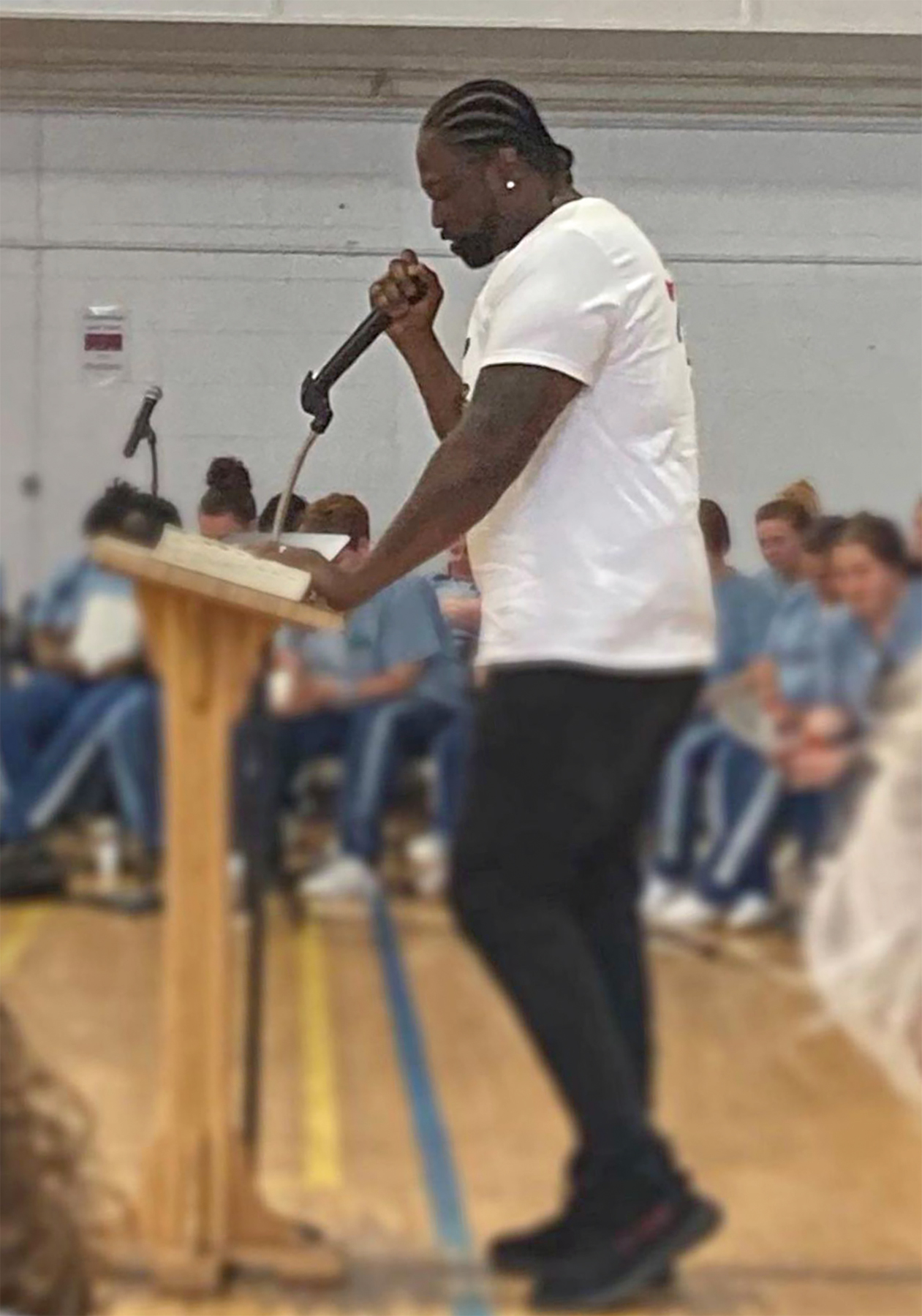

Anyone who follows Patrick Houston, better known as Project Pat, on Instagram will know that the Memphis rapper has spent the last few years visiting jails and prisons to preach the Gospel to the incarcerated. Best known in popular culture for his often-sampled and interpolated 2001 single “Chickenhead”—and for his visceral tales of street life in North Memphis—Pat began his path into prison ministry by asking God for guidance.

“People say, ‘God got something for everybody to do but, if you don’t seek Him out, you’ll never know,’” he explained in a 2021 interview with a Memphis pastor. “The Lord told me: ‘Go back in there.’”

Pat had already served three years of a nine-year sentence for aggravated robbery by the time he released his debut album, Ghetty Green, in 1999. But many years before that, he was saved at his father’s church on Jackson Avenue. His father, an evangelical Baptist pastor, instilled in him a belief in heaven and hell. In the church, he saw members of his father’s congregation putting blocks of government cheese on the offering plate. Outside, in the Hollywood neighborhood of North Memphis, he saw poverty and desperation, but he also saw the money some of the men around him were making through crack sales: the Lexus cars they drove and the gold chains they wore. Faced with a pious life of going without and the perilous road of something more, he made an easy choice.

It was Pat’s younger brother, Three 6 Mafia’s Juicy J, who showed him a third route. Driving J around one day in the early ’90s, dropping off his brother’s mixtapes at stereo stores around the city, Pat watched as J collected more than $20,000 in a matter of hours. Pat has never been shy about saying he got into the rap game for the money—he’s said as much in nearly every interview he’s ever done. It’s tempting to feel disappointed at this admission, as if every artist’s craft should come from a divine spark of inspiration. But this point of view has always been part of Pat’s appeal; he was at once an everyman and a neighborhood superstar. He taught himself how to rap by listening to nursery rhyme CDs and replacing the words. He took sayings from the pimps around the city and infused his music with their ism and their cadence. He told the story of his robbery arrest, and the revenge fantasies it evoked, on Ghetty Green’s “528-CASH.” When he rapped, he was to be believed.

As he told one interviewer: “I’m gonna either rap about something I know, something I been through, or something I know that happened.”

In his 2003 book Stagolee Shot Billy, author and educator Cecil Brown traces the lineage of one of America’s most popular and enduring ballads: the story of a St. Louis pimp who shot and killed another man in a barroom argument. The ballad has been present in nearly every form of American music, from jazz to rock & roll to rap. Among the folksong’s multitude of influences on rap, Brown notes, are its creation of an archetypical Black folk hero (one that the ballad initially imprinted in Black cinema of the ’70s) and—in a shift that took place during its performance in the 1960s and ’70s—a change in narration from the third person to the first person, which would become the genre’s staple. “The audience sees through the eyes of the character the rapper creates,” Brown writes. “It is the ‘I’ that makes the bridge between the ‘I’ of the rapper and the ‘I’ of the character.”

Project Pat’s first-person perspective brought his listeners onto the streets of a city where it seemed like death and betrayal lurked around every corner. The details of his stories, and the details of his own life, were part of a larger shift in rap’s narration toward a singular “I” of perceived authenticity. In a 2013 interview, he credited the success of his Ghetty Green follow-up Mista Don’t Play: Everythangs Workin, released in 2001, to the fact that he had left his past behind him. “I spoke in more details, because stuff had been over with and I was coming out of that street life and leaving it alone,” he said.

In this way, Pat helped advance a rap archetype that persists and pervades today—one that extends through Gucci Mane, the progenitor of Southern rap’s stylistic dominance throughout the 2010s, who has cited Pat as one of his main inspirations: the rapper who’s not really a rapper, who puts their experiences over a beat in the hopes of immediately changing the circumstances they find themselves in.

Photo courtesy Patrick Houston and Go Foundation

M ista Don’t Play: Everythangs Workin is the pinnacle of Project Pat’s catalog. By his second album, he had mastered the syllable-extending flow and cinematic storytelling that made him stand out even among Three 6 Mafia’s dark world of rappers and affiliates. There are buoyant, set-claiming chants; vivid details of licks gone awry; pimp anthems; weed homages; and some of the most ominous and forceful beats that DJ Paul and Juicy J ever produced. Pat balances out his hard edges, and his creative descriptions of causing bodily harm, with his sense of humor; the violence of “Gorilla Pimp” is somewhat offset by the back-and-forth playfulness of “Chickenhead.” Only Pat could make yelling “Bawk, bawk, chicken, chicken” sound as glorious as it does.

And then there’s “Life We Live,” the thirteenth song on the album, which strikes a noticeably different tone than the rest of Mista Don’t Play. As the strings and bells rise and fall, Pat wonders how he was able to “survive all this foolishness off in the street” and reflects on the recent death of his cousin, who Pat says was judged unfairly during his life. He makes more explicit references to God—the “only one who I’m fearing”—and the Bible than he does anywhere else in his catalog, offering the story of Lazarus’s resurrection as a counterpoint to those who think they’re invincible in the streets.

In the vast majority of his songs, Pat is always on the front foot, even when confronted with treachery and the confines of prison. On “Life We Live,” however, he allows for small moments of vulnerability that permeate the song. It’s not that Pat breaks character, but, alongside aggression and confidence, there are other emotions: pangs of regret, extensions of gratitude, words of encouragement. The simple truth of the hook—“This life we live / See it’s oh so beautiful”—is revealed through the plaintive chord progression: Often, this world is anything but beautiful, yet there’s so much in it that makes life worth living.

Listening to Project Pat may have granted voyeuristic access to a sinister side of Memphis, but it also brought the city’s language into a tradition where it could be repeated and repurposed. His early-aughts ascent led to more than a few go-go versions of his songs in the D.C. area. In recent years, Pat’s lyrics and cadences have shown up in songs by some of rap’s biggest names: J. Cole, Drake, and Cardi B. In true contextless fashion of the 2020s internet, samples from his verses and hooks can be heard as the backbone to an electronic subgenre coming out of Eastern Europe known as “phonk.”

“Life We Live” is not one of Pat’s storytelling raps—“We Can Get Gangsta” is his premier example of that strain—and it’s not one of his often-sampled or interpolated classics. But the song might have hinted at a nuanced “I” that was part of Pat’s lineage from the beginning. In Pat’s verses, we’re taken out of the cunning internal monologue that characterizes so much of his music. The tempo slows slightly, the sounds of the melody are softer, and reactionary actions are replaced with emotions. Pat asks us to have some faith in ourselves and, when we don’t know the way, in a higher power.

The song’s melody and chorus are lifted from “Oh So Beautiful,” the last song on the last album Curtis Mayfield ever made. Paralyzed from the neck down after he was hit by a falling lighting rig during a 1990 performance in Brooklyn, Mayfield recorded 1996’s New World Order one line at a time, lying on his back so air could more easily flow into his lungs. Like “Life We Live,” the original song dwells in the ups, downs, and in-betweens. There’s an overarching melancholy and a feeling of hope. As Mayfield sings, “To see the sun do shine / You gotta come out sometimes.”

On the third verse of “Life We Live,” Pat expresses a similar idea: “Gotta take the good with the bad, smile with the sad / Love what you got and remember what you had.”

A Google search of these lyrics brings up digital versions of inspirational quote posters, the kind you might find on the walls of a schoolteacher’s classroom. Some of them place plain white text over images of a wide-open road or horses riding off into the distance. Many of these images present the source of the quote as “unknown.” It’s possible the rhyme is something Pat heard from his grandmother or in church growing up, that it’s a saying that’s been floating around for decades, but it’s more fun to think that the seekers of meaning out there online, those scrolling by and looking for some inspiration, are being led to the words of Project Pat.