Plain Art

By Holly Haworth

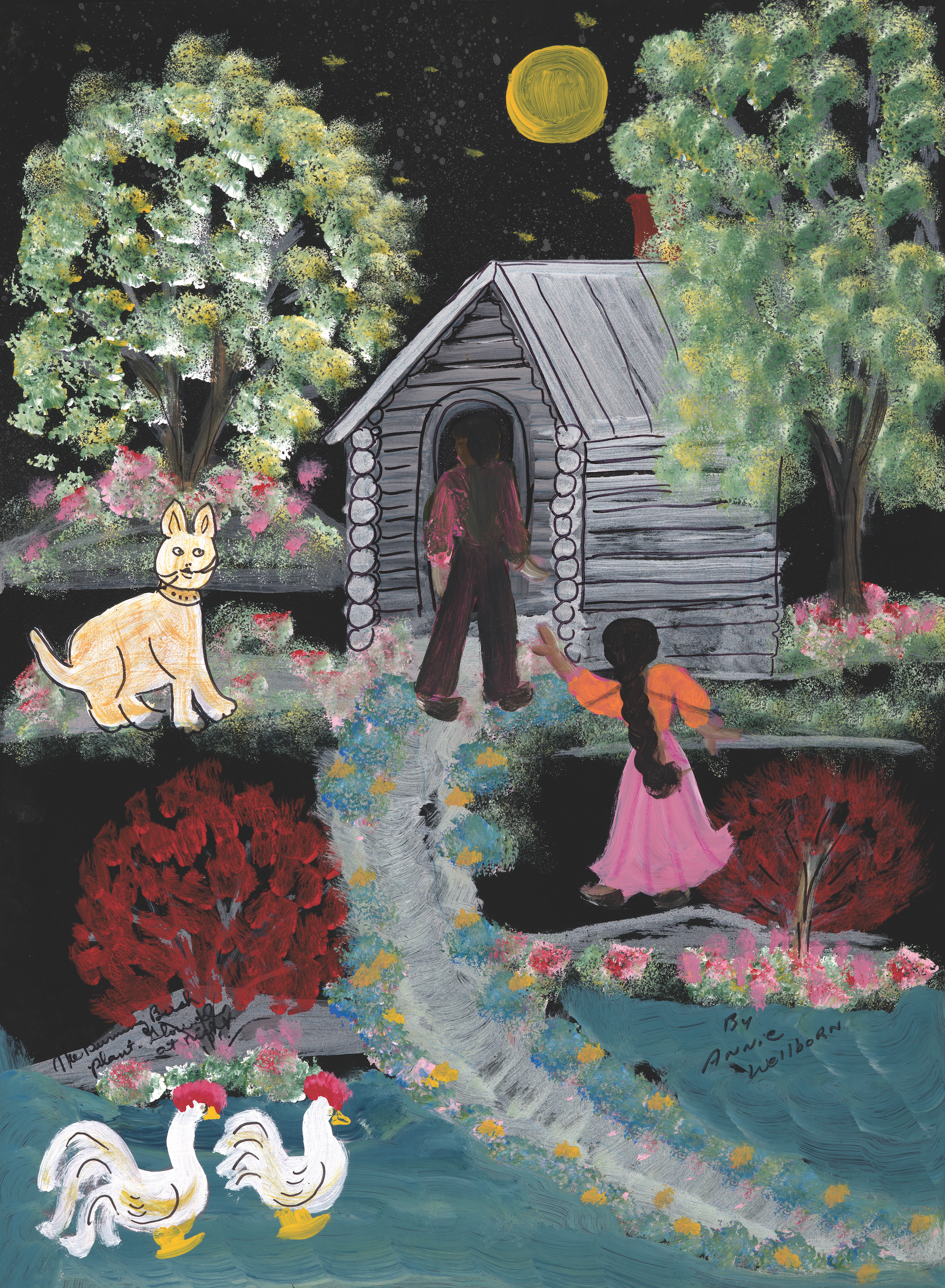

Painting by Annie Wellborn. Courtesy Robert Lowery

“Art happens—no hovel is safe from it.”

—James Abbott McNeill Whistler

It was not a brilliant painting, really. It was technically unskilled, the flowers in the yard taller than the people, the perspective of the walkway leading up to the house all off. The lines of the boards of the house’s siding looked to be drawn with black Sharpie, as did the painter’s signature, scrawled childlike in the lower right corner: By Annie G. Wellborn. Who was she? Why did her painting hang on the wall? Even for all its faults, I was drawn to it inexplicably. It seemed to radiate something to me in that mysterious way that art sometimes does.

“Who’s Annie Wellborn?” I asked the neighbor, Robert, whose home I was visiting. He raised his eyebrows and pointed to the massive black-and-white photograph portrait he had taken of a woman in a floral cotton dress with a lace collar and a man in slacks and a plain cotton button-up shirt, both smiling with hands clasped in front of them, standing in front of a house with fading paint and crooked screen door, a cinder-block foundation. That was Annie, his friend who had lived nearby in Bishop, Georgia, he said. She stood with Carter, the disabled brother of her deceased husband Jimmie, who lived with her after Jimmie died, until her own death. “One of the most important people in my life,” Robert said. Late for an appointment, I had to leave. Days afterward, though, I thought of the painting and wondered again about the painter.

I went back to visit Robert a few weeks later. “Who was Annie Wellborn?” I asked him again. He sat down in a rocking chair on his front porch, and I sat in another one. He told me that nearly twenty-five years ago he had a dream of flying. “It was so real. It didn’t seem like a dream. I kid you not, I went somewhere. I went to some place.” He shared this with a mental health counselor. Soon afterward, he found himself in a psychiatric institution against his will, wrongfully committed. The whole debacle only lasted for a day or so, and after he got out, he was at a Tuesday-night town meeting, where “this little old lady walks up to me and says, ‘you need to come see me.’” He’d heard her name before. He was at that time the owner of a local art gallery and something of a collector, and she was a painter whose work didn’t interest him.

The next week he went to see her.

“I drove out to her decrepit trailer and sat down with her, and I asked her, ‘Why did you start painting?’” She told him she had nearly died of a disease that had killed her uncle. When she was hospitalized, doctors said there were too many risks involved to perform a surgery. That night, Annie told him, God came to get her from her hospital bed and took her to heaven, where people were flying. God said, “Annie, I’m not done with you yet.” The next day she gathered the nurses and doctors and told them of her visit to heaven. Instead of sending her to the institution, they agreed to perform the surgery.

Robert interjected to ask Annie how high they flew in heaven. He was just curious. “She’s sittin’ in this old recliner, and she says, ‘Just like this, right up off the ground,’ holding her hand just halfway up her shins.” That happened to be the same height Robert flew in his dream, though he hadn’t told her about it yet, and he never did tell her. “‘Me and you’s got somethin’,’ she told me. ‘I’ve been waitin’ on you. This ain’t nothin’ romantic, you understand, but me and you’s got somethin’.’ So me and Annie were super tight from that moment on.” Robert’s not a religious man, a fact he makes frequently and forcefully clear. “What does it mean?” he said. “I don’t know, probably not a whole hell of a lot, but what she said to me was somethin’ special.” He was blinking tears out of his eyes. We rocked in our chairs and looked out at the changing leaves on the water oaks in the yard.

When doctors saved Annie’s life with surgery in 1978, she was fifty years old and had never picked up a paintbrush. Robert told me, “That’s when she started painting, and that’s why she started painting. She said, ‘That’s why God keeps me around.’ She understood how important her life was because she almost lost it.”

Photo of Annie Wellborn and her brother-in-law Carter Wellborn by Robert Lowery. Courtesy the artist

In the house, Robert pulled out more of her paintings, tucked away in large drawers. Soon, I was sifting through a pile of some twenty canvases he had bought from Annie, or that she had given to him, refusing payment, during the ten years he knew her until her death. All that time, he said, she had painted every day.

One of the pieces depicted a couple standing in front of a house with a white cat, daffodils blooming along the walkway. The house sat on stacks of bricks at the corners. On the painting, she had written “1946. Jimmie Wellborn, Annie G. Wellborn. Jim and I thought all we needed was each other. We worked together to make our home pleasant. Made almost everything we had.” This was one of what she had called her Memory paintings: scenes from the past with memories written at the bottom or on the back.

Another was on black paper. Again, it featured a house. Yellow, with two red-brick chimneys. A woman and man, a cat. Her words said, “We weren’t underfed and never wore ragged clothes. We might have, but Mama was a good seamstress and knew how to make a yard of cloth go a long ways. And she knew how to take a sock and rags or material and make beautiful quilts.” This was one of what she had called her Mysteries of the Night paintings: all of them on thick black paper, many of them with vivid, almost neon, acrylic paint. Also with memories written on them—Robert said he thought she began this series as a spinoff of the Memory paintings because one of her daughters worked at a sign shop and brought home the paper scraps. “She made use of whatever people gave her,” he told me.

Nearly every painting, whether Memory or Mystery, was a variation on the same scene: a couple of people, sometimes a child or two, standing in front of a house, in a yard with flowers, sometimes a cat or dog. This was true of the first of her paintings I’d seen, the one framed on the wall. It features a faceless woman and man, both dressed in blue, standing in a sloping yard, a house perched on the hill before them. Between a small shining pond lined with cattails and a rickety backyard fence, Wellborn had written in a messy script: “So many memories. Some good, some bad. Some very sad. Most good of Mom and Dad.”

The houses are all a little different, the doors and windows in different places, the red-brick chimneys slightly varied. But they are all houses, most of them flanked by a tree on either side. Her subject matter, I thought, as I looked through the paintings, revealed the very narrow limits of her abilities. She lacked skill, which kept her confined to these houses. But still, I was touched by something, and as I kept looking, I saw in the paintings, perhaps, a deeper obsession, a more deliberately chosen subject than I had at first imagined, one that kept her occupied—even inspired—as an artist, though her work was so plain and simple, and the word inspiration seemed a bit lofty.

One of the Mysteries of the Night paintings depicts a black house with white porch railings and window frames, trees aglow with golden leaves, a woman, a man, and a young girl that I take to be the young Annie with her mother and father (though she was one of eleven children, she had told Robert). They are all facing the house, waving at it. Faint stars speckle the black above the roof. Her words in cursive next to the people say, “The house is there. If it could talk it would have some pretty interesting tales. They wouldn’t be boring. Wish it could tell us the stories Grandma sat on this very porch and told us Grandkids.” If these walls could talk, a trope so common it’s cliché. And yet, the more I looked at the paintings and read her words, the more alive the houses seemed, almost humming.

Another Mysteries painting shows, again, a couple with a young daughter standing in front of a house. A round yellow moon rises above the pitched roof, polka-dot stars spangling the night. All the windows and doors of the house are gaping open, the house inside full of darkness. Her words, looping across the yard, say, “The homes are vacant. The memories of long ago. The homes wait for noise so I guess Annie occupies and breaks the silence. But this is not enough so they finally give up and collapse.” Her painting was a way to occupy the houses still, to break the silence of time and keep her memories standing, to show how her life, though it seemed as plain as it gets, had been vivid—after she understood how important her life was because she almost lost it. One of the Mysteries paintings has a bush in the yard with red foliage. The words say, “The burning bush plant glowed at night.” After the surgery that saved her life, she painted so prolifically and distributed her paintings so widely, giving many of them away, that the folk-art collectors Chuck and Jan Rosenak somehow caught wind of her work and featured her in their 1996 book Contemporary American Folk Art: A Collector’s Guide. Southern folk art was experiencing a boom at that time, and collectors from across the nation began to drop in on Wellborn at home to purchase her pieces.

Painting by Annie Wellborn. Courtesy Robert Lowery

There is a long and wide-ranging debate about what folk art is, but I am of the mind that Wellborn’s work—not carrying on a cultural or community tradition, not of a lineage of artists—would be more rightly called naïve, a class of art characterized by a lack of training and technique. Naïve painting like Wellborn’s, or the work of Mose Tolliver or Jimmy Lee Sudduth, for example, is childlike, untrained.

Robert placed her notebook before me. She had bequeathed it to him sometime before she died in 2010. She had wanted people to read it, he said. There was a page titled Mysteries of the Night. And so I read it as a kind of key to unlock her Mysteries series, something to explain to me what was in all these houses filled with darkness. I read the following:

The old houses are still standing, but they will soon get lonely and die. If each one could talk they could tell some more mysteries. They would tell us how they miss the chit chat around the big fireplaces. Also the memories of music that was played by the family on Saturday night. Didn’t have TV then or not many radios. Mama sang Put My Little Shoes Away and I’ll Meet You at the River. Her voice was so beautiful. Dad played the violin. His sister played piano and organ. Grandpa played the saw. Boy could he make it sing. The other brothers played banjo, guitar, mandolin. I beat the spoons. I had to have a certain kind to sound right. But I could beat the sound out of them. I was small but dad said no one could get the sound like I could. The echoes are still there. But the buildings are all gone now. The mysteries are still in my mind.

Family bands were still common in the 1930s, when Wellborn was a child. People still sang and danced at home in the evenings when they did not yet leave it only to the machines to play their music for them, and art was not something they had to go to a museum to see. I understood, then, finally, what all the houses meant. What she had tried to preserve in her paintings was the memory of the art made by those who lived in the houses—how she and Jimmie made almost everything they had, how her grandmother spun stories on the porch, how she banged on the spoons and her mother sang, how her mother made beautiful quilts from scraps and her grandpa bent the saw into wild notes.

Even more, I realized that her paintings were made during the last thirty-two years of her life, the life she lived in a trailer, and then, later, in a house that was falling in on itself, Robert had told me, with the brother of her dead husband and almost no money as she struggled with her failing health. A very plain life by all outward appearances. Even drab, even difficult. But her paintings were so colorful, joyful, innocent, naïve. Robert told me he had a memory of visiting her late at night near the end of her life. As he climbed the steps to the porch, he looked in the front window of the house and saw her sitting inside at the kitchen table, hunched over a painting, dabbing her brush at the foliage on the trees that flanked a house, and smiling to herself. These paintings I was looking at were, in a way, just objects, created within the limitations of her life’s confines and her skill. They weren’t the feeling she got when painting, immersed in both the memory and mystery that are inherent to making art, however plain it may be.

One of the definitions of naïve is “artless.” We have lost a lot of the plain and everyday way of making art even as we have worked to preserve collections of paintings in museums of those we consider true artists. And we have called untrained artists naïve. We have left art to the masters and overlooked the houses in which plain people live as being artless. Wellborn was working to preserve the memory that every house might be full of artists. She was continuing in her mother’s lineage of making quilts from scraps as she used sign-shop leftovers for her paper canvases—she was, then, a folk artist, carrying on a vital tradition. The brother-in-law Carter, inspired by Annie, also began painting, and Robert showed me one of his, on plywood: childlike, but not naïve. Not artless. Whimsical, strange, a medley of people and animals replicated in multitudes. Folk-art collectors acquired his paintings, too. By painting her memories of how her family made art out of plain life, Wellborn was continuing to do just that in the present and inspiring her family to do the same, and we don’t speak often enough of the profound substance and sustenance that art can provide to the artist.

Seeing the paintings Robert showed me that day, I worried that collectors have fetishized “folk art” while we have forgotten to keep the lived practice of plain art alive. Robert agreed. I left with the memory he shared of seeing Wellborn through the window of her house. On the outside, as I had seen in the black-and-white portrait on his wall, the house had looked like nothing much, maybe even downright ugly. But inside, in the dark night, there was Annie, painting on paper scraps and smiling. I imagine she had a feeling a little like flying, just right up off the floor, maybe—which, it turns out, is a very common dream.