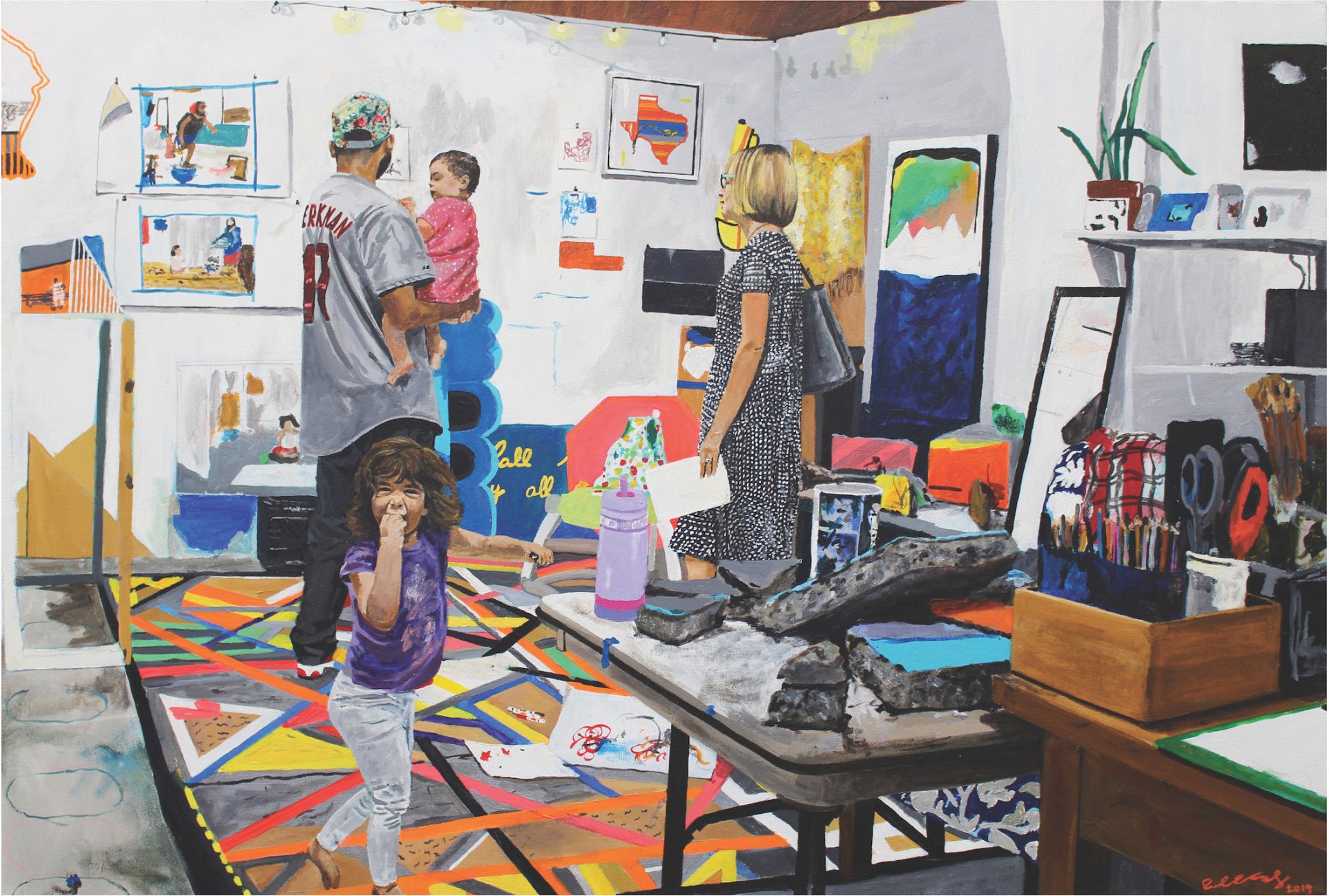

Studio Visit With My Gallerist Jill (Moment Captured by June), 2019, acrylic on cotton duck canvas. All artwork © Raul Rene Gonzalez from the series Doing Werk

The Mythic and the Everyday

Artist Raul Rene Gonzalez finds the beauty and the iconic in domestic life

By Michelle García

We have ninety minutes, the length of the movie that artist Raul Rene Gonzalez has cued up to keep his two young daughters entertained while their father answers questions about the artist life, which to him is the stay-at-home father life, life as the son of working-class parents, and life as part of the artist community in San Antonio, Texas. In his work, Gonzalez reimagines familiar symbols and scenes to celebrate, even mythologize, everyday life. Artists are shown parenting in their studios; men who wear hard hats to work become iconic.

Midway through our computer-enabled discussion, the sound of Vicente Fernández’s classic “El Rey,” with the lines, “my word is law … I remain the king,” rings through my building in Mexico City. The next day, I notice on the subway platform a public service campaign with the slogan, “It’s time to change! – men are nurturers and homemakers.” It was as if the physical world was amplifying Gonzalez’s observations that artistic renderings can work to upend stereotypes of men of color and expose their absence in other areas of life.

News stories deliver almost daily reminders of the ongoing political erasure of Latino/a and Latinx. Politicos in Texas, where both Gonzalez and I were born and raised, brag about the booming economy and the scores of residents moving into the state. But left unacknowledged is the role of Latino/x as the engine of population growth. And that the ethnic group, now the nation’s second-largest racial/ethnic demographic, is the largest in a state that has made it easier to buy a gun than cast a vote, a state governed by minority rule.

Theirs is an existence that gives meaning to and complicates the phrase “representation matters,” which includes both families with generations-deep roots and recent arrivals, people who are revitalizing cities and towns, imbuing culture in their communities, whose unrecognized sweat and labor build our world. Gonzalez’s work encourages a reflection on what it means for a people to be everywhere—serving some of the best damn pupusas outside of El Salvador in Athens, Georgia; rebuilding New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina; working in a multi-racial coalition to defend democracy in North Carolina; transforming the poetics of Kentucky—and yet largely unacknowledged culturally.

But not to Gonzalez, who belongs to a generation of artists who care little for knocking at the door of acceptance when they can render their own doors to celebrate the beauty in the ordinary.

With paintings and sketches braiding together working life and parenting life, Gonzalez’s pieces remind me of the questions posed by poet Bertolt Brecht:

Who built the seven gates of Thebes?

The books are filled with the names of kings.

Was it kings who hauled the craggy blocks of stone?…

In the evening when the Chinese wall was finished

Where did the masons go?

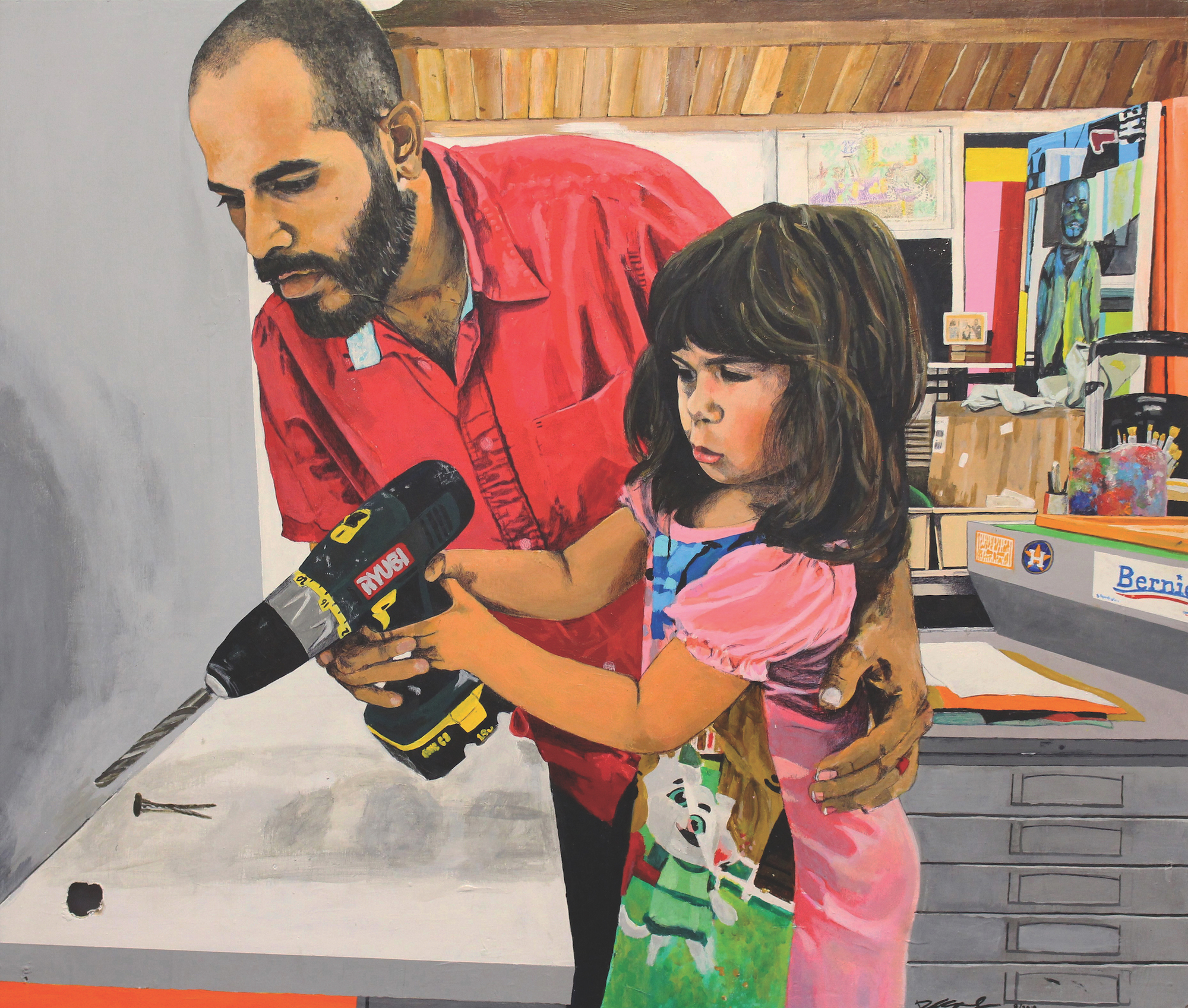

Morning Drill Lessons With June, 2019, acrylic, ballpoint pen, and colored pencil on wood panel

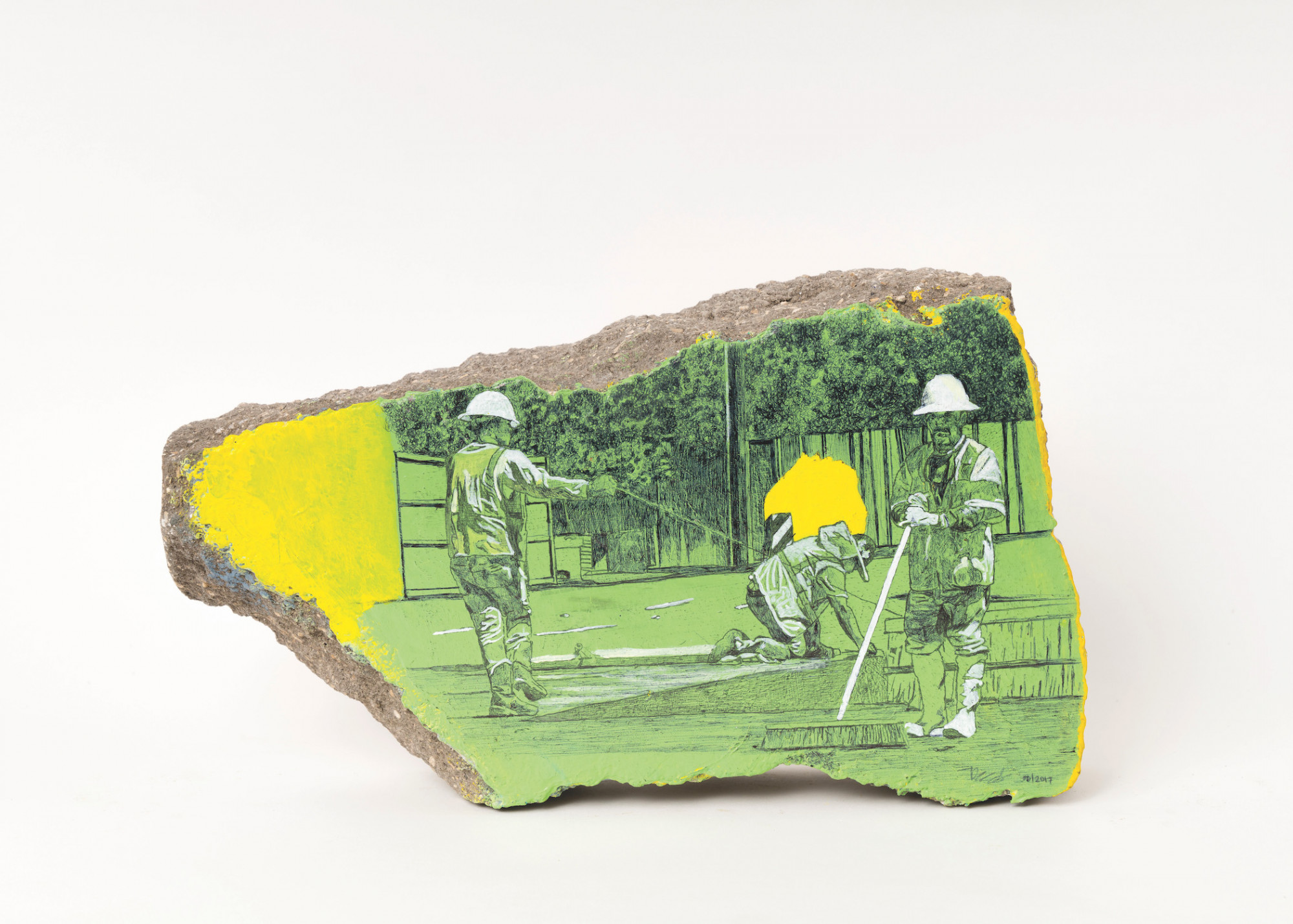

Michelle García: Your piece Work Vest and the pieces painted on concrete slabs I see as an honoring and mythologizing, doing for the Mexican American, Latino, Latinx workers in Texas what previous generations and artists have done for dock workers in New York or Dust Bowl migrants and railroad workers. I wanted to talk a bit about that sense of creating a mythos.

Raul Rene Gonzalez: My dad is sixty-eight years old and he is a machine operator, [using] the loaders, the bulldozers, basically heavy equipment. My first official summer job where I got a paycheck was working construction with him. But, it’s funny, I wasn’t really inspired by it until I was in my twenties, [back] when I was a delivery driver for a printmaking company.

I used to drive around Houston four to five hours a day seeing construction everywhere and listening to people talk about it. Most people complained about construction, and I got really annoyed by it. Why are people not respecting this work?

I started making work about construction because I wanted people to think about [the labor] when they’re driving around and they’re at a stoplight and they see these people working. I want them to be like: “I respect what [those workers are] doing, I see what they’re doing.”

Once I started using the concrete pieces, it was almost like I was making pieces of a long mural that should have been made in the first place. Like each one of these is a piece of a big[ger] picture. If you put them all together, you’re going [to] see the scenes of construction being built everywhere.

And seventy to eighty percent of those construction workers in Texas are Latino, Latinx, Mexican American. But the Texas construction workers are also among the least paid, [and they perform the] most dangerous work. You feel the sense of political disposability in the backdrop of these pieces.

At the same time, you appear to be part of a generation and part of a movement of artists who are honoring working-class life. I’m thinking of Arleene Correa Valencia in California, who made sweatshirts with stripes of construction reflectors on the back and printed on the front: “Somos Visibles” (we are visible); Jenelle Esparza in San Antonio with her work on cotton (which generations of Texas Latinos picked, including my mother). And you guys seem to be saying, “We are not going to be shamed for where we come from,” right?

There are a lot of us artists who are acknowledging our past. Our past is what made us who we are, and each aspect should be recognized. There should be no reason to be ashamed of it or to let it go. I should be proud. And the same goes for, more recently, making work about artists who are parents.

Smooth, Like Criminal, 2017, acrylic, house paint, and archival ballpoint pen on concrete. Private Collection. Courtesy grayDUCK Gallery

When I first came across your work on parenting, such as Artist Teaching Daughter How to Use Power Tools or Hammer Time With Cecelia, they made me think: These are images of Latino men nurturing and parenting and caring. And I began to wonder if my reaction was itself a stereotyping.

We think it’s not common because we just don’t see it. And that’s the problem. I feel like, okay, I will be that guy. I will show my life story because other people need to see it to realize that it’s okay. I’m [a father, too], and I don’t have to be ashamed of it.

But there’s a backstory. When I was fifteen years old my first official job was as a babysitter. I used to babysit my [younger] cousins, and I did that for a long time. After babysitting them for a little while, I thought I could share some babysitting advice with my mother. And my mom would be like, oh, you don’t know what you’re talking about. She was like, when you get older and have a baby, you’re going to be calling me all the time: Mom, I don’t know how to do this, Mom, I don’t know how to do that. I never forgot it.

Once my wife and I had our first daughter, we had a conversation and decided that I would put off being a professor. I decided to be the best dad I can be, knowing that I needed to learn a lot of stuff and I needed to grow as an individual.

My daughter and I would do things, and I thought, oh, wow, that was a nice moment that we shared. Maybe tomorrow we’ll do the same thing, because I’ll set up the camera.

There seemed to be a whimsical aspect, but also a kind of designed architectural element to the work as well. In The Golden Age of Construction and in the parenting series.

When I was a kid, when we used to just drive around the city, I used to just stare out the window and think, how would that be drawn? What would the lines look like if it were a drawing? When I was in high school, before I thought I was going to become an artist, I was really into math. I was in a math club and I thought I was going to go into architecture or engineering. It’s always been there for me, drawing things with design elements, like a blueprint.

You create images of other fathers, not just of yourself. There is one of Houston-based artist Robert Hodge sitting on the porch with his daughter, and he seems to be imparting a lesson to her, right? The one of Matt Manalo and his son at a loom? I come away too with the sense that they are not separate—the parenting and working series—they’re integral to each other. Here are these men of color, Black men, Asian men, Latino men who are performing a service for their families and are also imparting wisdom.

I wanted, with all the series, [for it] to feel like [the men are] on the same level as their kid. Like they’re not trying to be talking down to them. There’s not always an embrace, but there’s that moment of sharing. Like, this is for you. The intimacy.

Raul Rene Gonzalez is an award-winning multidisciplinary artist who incorporates a wide range of media and methods in his paintings, drawings, sculptures, clothing, murals, installations, and live and recorded dance and performance-based work. Largely autobiographical, his work explores topics such as fatherhood, gender roles, labor, identity, pop culture, science, and abstraction. Gonzalez’s work is included in permanent collections of the McNay Art Museum, National Museum of Mexican Art, National Hispanic Cultural Center Art Museum, and many more.