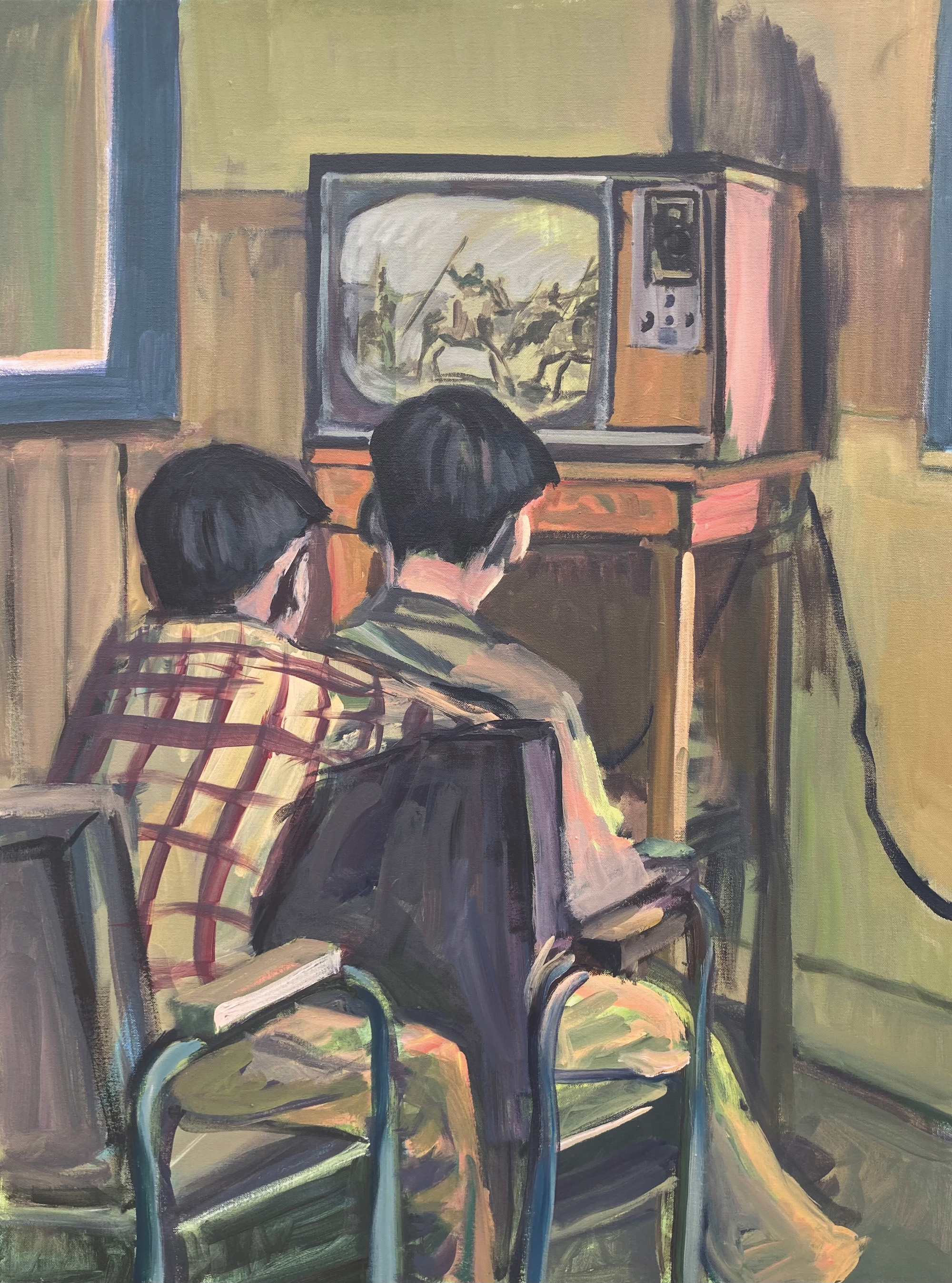

Blood Brothers, 2022, acrylic on canvas. All paintings by Marcus Dunn © The artist

Re/Educated

On painting a new record of Indigenous history

By Marcus Dunn

My Native community, the Tuscarora Nation of North Carolina, assimilated very early in the era of colonization: first, after the Fort Neoheroka Massacre of our people in 1713, and then, when our Tuscarora reservation in Bertie County, North Carolina, was sold/taken from us in early 1828. Over time, after migrating to the Southern swamplands, we had to learn to survive by adapting to local trends in farming and agriculture, and our gradual disconnection to our traditional ways led to forgetting our languages and sacred ceremonies. Over the years we have worked to bring back things that were lost. In the late 1920s, some of our leaders worked with the Mohawks from Akwesasne, New York, to re-establish the Longhouse tradition and bring back the culture. My great-grandfather Isaiah Locklear was involved at that time, but traditional practices were later dismantled in the 1950s by local churches within our Native community. Today we are working hard to revitalize all facets of our culture, through language, songs, dances, and ceremonies, and through building our relationships with the Haudenosaunee up north.

Girls on the Back Path, 2019, acrylic on canvas

My paintings are based on the long history of removing, conforming, and killing Indigenous people in the United States. This work is also a way to decolonize the historical narrative of indigenous boarding schools. Colonel Richard Henry Pratt was the primary organizer of the boarding school system. He was known for his mandate: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.” Carlisle Indian Industrial Boarding School was opened in a former prison barracks by the federal government under Colonel Pratt. It was called an “industrial” boarding school, designed to prepare boys for manual labor and farming and to prepare girls for domestic work. Children were not only introduced to a new style of learning curriculum but also exploited as a labor resource, forced into factory work at the school. The schools were a new path to “cleanse” Native people in addition to the construction of the “reservation,” which was designed to assimilate all Native peoples across Turtle Island (America). Reservations placed Indigenous people in underdeveloped or unwanted areas, prevented natural migrations, and reduced the surveying of the land for traditional ways of hunting, fishing, agriculture, and trading. It was a way of killing the people: physically, mentally, and spiritually.

I began the RE/EDUCATED series in 2017, covering the problematic history of indigenous boarding schools, which has become increasingly more visible today. Over the past several years, investigations of unmarked grave sites at many of the former boarding school locations have found over 1,000 unmarked graves in Canada, and it is estimated that over 40,000 children died at Indian boarding schools in the United States. These numbers will likely continue to rise as more research is done. Nearly all residents, children between six and eighteen years of age, were involuntarily transplanted to locations away from their homes without the consent of their parents and other family members. RE/EDUCATED is a glimpse into this episodic realm of traumatic circumstances, the forced re-education of children who attended boarding schools, and the current re-education of the public about the schools’ problematic past. My paintings are composed of images that reimagine what may have been and may spark reflection on memories entirely unrelated to these traumatic situations.

Cowboys & Indians, 2022, acrylic on canvas

Left Ajar, 2022, acrylic on canvas

The art I am making has been a way of re-contextualizing this painful past to give a voice to the individuals who were not allowed to live as human beings by giving them an identity. The survivors are people who have fought to retain what cultural knowledge they had and have worked to revitalize their languages, songs and dances, and ceremonies. The paintings confront feelings of displacement, loneliness, sometimes joy, but more often trauma and sadness: a need for escape. I frequently paint my figures in moments of isolation, sometimes seen from behind. This first-person perspective enables the viewer to enter the paintings’ space, as the subject enters theirs. One example is from Left Ajar, showing a figure standing in an empty room with a door ahead of her slightly open, suggesting two paths, two choices. These images often stem from my interest in cinema and the kind of narrative storytelling that invites the viewer to follow the subjects while they are most vulnerable, which allows their emotions and thoughts to resonate on an even more personal level. My work aims to adhere to those emotions, to open a window into the world of happenings, conflicts, and relationships that were built during the boarding school era.

One of my goals is to travel to former Indian boarding school locations and reservations impacted by the removal, relocation, and thieving of their children. This would afford the opportunity to meet some survivors of the schools and their descendants, and to learn more of the truths of those that were taken from all that they knew. They were youth who were stripped of their culture and way of life, and obliged to learn contemporary non-Native societal norms. I want to visit different Indian reservations throughout the United States and Canada that were targeted for forced removal of children to the schools. I want to explore old remains of the schools to use for references when creating narrative scenes in my paintings to further address the psychological effects of space and place. While many of my paintings are based around the time the schools were in operation, I intend for the new works to reflect those Native communities today.