Freezer Songs

By Josie Tolin

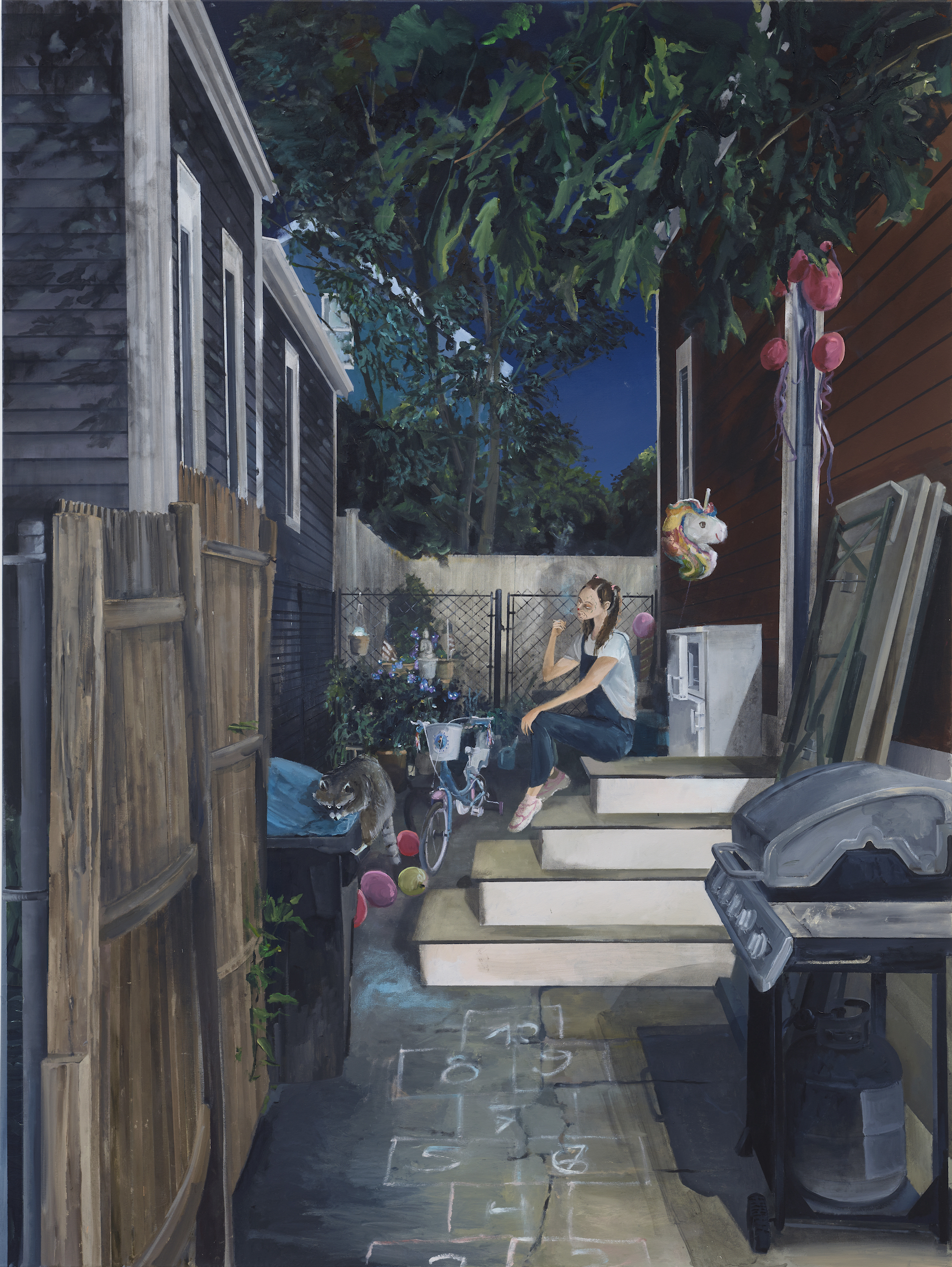

Piano Chesterfield Dreams, 2021, acrylic on canvas by Tim Sandow. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Droste

The summer Blake Shelton and Miranda Lambert finalized their divorce and a couple of months before I quit Jimmy John’s, I was complaining about the hoagie rolls to my coworker and almost-lover, Benji. “They’re bizarre,” I said. I tossed a tomato slice into the air and caught it on the tip of my serrated knife. “I don’t think this place would be so popular if people knew they were eating bread that’s been frozen rock-solid.”

“It’s fast food, baby. No need to reinvent the wheel.” Benji slid hot-pepper rings onto each of his nine fingers. He wiggled them at me. He was not my only coworker who called me baby, but he was the only one I didn’t want to punt when he did it. Benji was pimply and had very defined dimples on the rare occasions when he smiled. His tenth finger had been sawed off while he was making a wooden coffee table with his father. After he told me the story he showed me photos of the finished table. It looked lopsided, but I didn’t say so.

The door chime sounded, and the Fedora Man walked in. I wasn’t looking because I was still admiring Benji’s pepper fingers. My manager tapped my shoulder.

“To the freezer,” he whispered, pulling at the bill of his visor.

The Fedora Man was stalking me and all of my coworkers knew it. I shut myself in the walk-in and crouched next to a stack of frozen meat blocks. I felt cold, but it was a manageable coldness, not like those first few shifts after I realized the Fedora Man had memorized my entire work schedule. At this point I had committed the routine to heart, knew the exact amount of time it took the Fedora Man to pretend to ponder the menu before ordering a Beach Club on wheat, hold the tomato. It took Benji about thirty seconds to toss the sandwich together, peeling butcher paper from the turkey slices, layering them with guacamole. The Fedora Man would ask after me and Benji would say I wasn’t there. Then the Fedora Man would grab his sandwich and barbecue chips, scan the faces behind the counter, and, so long as I stayed out of his line of vision, would leave.

“He probably has a thing for redheads,” my sister Sylvie said later that evening. She was two years older than me, had just finished her senior year of high school, and would start at Ball State in the fall. Her limbs were long and her bangs were short. She didn’t have a lot of friends. “There’s an entire porn category for your hair color.”

“Fantastic,” I said. We were watching Spice World on the scratchy green couch in our living room. I got nauseous every time I pictured the Fedora Man, his skinny face and Mona Lisa eyes, which could follow a body in motion while the rest of him stayed still. My coworkers never brought him up except to signal that I should hide. At the time I was grateful for that. “Which Spice Girl are you, and which one is me, and which one is Dalia?”

“I’m Posh,” Sylvie said. “You guys can be whoever.”

We’d known Dalia since we were little. She was one of seven kids at our synagogue—a small, brown rectangle with Star of David window clings, located thirty minutes from our house in Boone Grove, Indiana. Often, Dalia joined us for family events, including our little cousin’s bris, a specific kind of intimacy. Like most people, she both feared and respected Sylvie.

About a week back, when Sylvie said we should start a Jewish country music trio, Dalia and I had had no choice but to agree. We were walking through the woods behind my house, which went on for miles. As we hiked, Sylvie counted the tree stands under her breath. If there was a hunter up there, it counted as two. She didn’t say why, and Dalia and I didn’t ask. Night had dimmed the spaces between the branches when Sylvie said, “I have an idea.” We all stopped walking. On either side of Sylvie, Dalia and I leaned in.

This is how Sylvie laid it out: she would be our lead vocalist; I’d play acoustic guitar. I hadn’t touched a guitar in four years and had played for just two in the first place. The only song I remembered was “The Star-Spangled Banner.” I didn’t say this to Sylvie because I knew she knew and after dinner that same night I dug an old guitar pick out of my nightstand drawer and practiced chords until my fingers hurt.

Dalia would fiddle because she’d been in the school orchestra since fifth grade. “I’m second-to-last chair,” she said shyly, but Sylvie either didn’t hear her or didn’t care. On our hike back to the house the ground squished beneath our gym shoes.

Dalia and I weren’t sure where Sylvie got the idea. Sylvie only liked the old stuff anyway, Hank Williams and Willie Nelson. Dalia worshiped Kenny Chesney. Dalia’s country music obsession must have had something to do with coming out to visit us all the time, something in the stretches of cornfield that lined County Road 260 or in the vastness of the clearing we reached on our hikes out back, a spot we had to press through thorny tangles of branches to get to. When it came to country, I had always been conflicted. Three summers earlier, Sylvie, Dalia, and I had pulled on our cowboy boots and ventured to a Luke Bryan concert at the Porter County Fairgrounds. Sylvie and I swayed in the back with our arms crossed while Dalia whooped and hollered, waving her hands to the beat of “Country Girl (Shake It for Me).” After, while standing in line to purchase lemon shake-ups, a reporter appeared and asked for a comment on the show. I answered before Sylvie or Dalia could get a word in, telling the woman I enjoyed the lonely warmth of Bryan’s sound even though his lyrics were often redundant, often boring. For weeks Sylvie scanned every local news outlet for my quote, and when it didn’t show up, she told me I should step aside the next time we were approached by the press.

Sylvie had always been the ideas person, ever since the days when our parents used to drop us at the temple’s children’s seder. We were supposed to reach our index fingers into the Styrofoam cups and blot along the edges of our paper plates, one grape juice drop for each of the ten plagues.

“What if…,” Sylvie whispered, and everyone leaned in, all six of us. “What if we dipped our noses into the cups instead of our fingers?”

So we all stuck our noses into our juice cups and of course I knocked mine over. The rabbi was a mean Israeli woman who kept her short curls gelled, so they didn’t even move when she paused her Haggadah reading to whip around and glare at us. Then Dalia, always in her own little world, went and copied us while the rabbi was watching. She came up sniffling, purple droplets still falling from her nose tip.

“Outside,” the rabbi said, meaning Dalia and me. We shrugged, then waved goodbye to Sylvie, practically skipping as we made for the field behind the temple, which shared a border with a middle school playground. Boys were playing soccer, many of them shirtless. Our Passover was not without its little miracles.

Now, on our way to Friday night services, Sylvie goaded our parents into changing the radio station from rock to country. “I’m trying to educate Rachael,” went her all-time favorite justification, the same one she’d used for our screening of Spice World.

“Whose bed have your boobs been under,” I sang from the backseat.

Sylvie elbowed me in the side. “It’s boots, idiot.”

“I knew that,” I said, convincing no one but myself.

I spent some of Shabbos morning on my knees behind the Jimmy John’s dumpster, giving Benji a blow job. We played chess on our lunch breaks and whoever won usually got oral from the loser before the following shift. The pavement was peppered with sharp pebbles that felt like they might break skin if I shifted. Sweat pooled at my underboobs, trickling down my stomach. Gnats whizzed behind my head, less interested in us than the garbage, the damp sting of its stink.

“Maybe the loser could get head sometime,” I said, wiping my mouth on the sleeve of my t-shirt as he zipped his fly.

Benji had a serene expression. The whitehead between his eyebrows looked ready to pop, and it took all my willpower not to pinch it right then.

“Rules are rules, baby,” he said.

The Fedora Man never came in on Saturdays. Probably he had hat-related obligations, or other girls to terrorize. Business was slow. Our manager offered to give someone a hundred dollars if they ate the glob of guacamole off the side of the trashcan and Benji licked it up without missing a beat. For lunch Benji bought me a veggie sub with Dijon and I thanked him three times even though it came out to $2.75 with his employee discount. We parked ourselves at the corner booth, backs stiff against the laminated plastic. He pulled the chessboard from his bag and checkmated me in five moves. I flicked the cross on my king’s head and the piece rolled across the board. Benji smirked at me, flashing his dimples.

“Would you want to hang out this weekend?” I asked. “We could see a movie or go for a hike.”

“I’ll think about it,” he said. He packed up the chess set. We clocked back in and tossed a pickle back and forth for half an hour before our coworker Marco snapped at us. Marco had a lumberjack beard, so he looked like a natural on meat-slicer duty.

“If you guys keep this up, my hand will look like Benji’s by closing time,” he said. A thin sheet of roast beef fell onto the tray in front of him.

“Fuck you,” Benji said, then took a loud bite of pickle. The chime rang and we all stiffened. A short woman walked in with a toddler in her arms and a mean look on her face.

“Welcome to Jimmy John’s,” I said.

Besides the crickets in the evening and occasional gunshots from the hunters during the day, Boone Grove was very quiet. I did not always enjoy hearing my thoughts so clearly. I thought most about the Fedora Man when I was trying not to think about the Fedora Man. I had a lot of trouble sleeping that summer.

My mother owned a bunch of smutty books set in prehistoric times. I wasn’t supposed to read them, but my parents were heavy sleepers so sometimes I’d nab one from their closet during a bout of insomnia. My favorite featured a traveling caveman and his outrageously large “manhood.” We also had some cowboy erotica in one of those basement boxes no one had ever unpacked. The men on the covers looked like wax dolls. People had sex on horseback.

Books were good distractions, until I finished them for the third, fourth, or fifth time, and then it was just me, my lava lamp, and the ceiling, which had a stain shaped like a lasso that I loved to stare at. One morning my radio clock flashed 5 A.M. and I hadn’t slept a minute. I plugged in my lava lamp and began to pace. I felt the way you do when you walk out of a basement and into the daylight, only my body wasn’t interested in adjusting to the world. I heard the faint whistle of the shower and knew my father was up, getting ready for work at the steel mill. A clanging downstairs meant my mother was stirring sugar into both their coffees. I twisted the dial on my clock until I found 95.5, the country station, which was doing some sort of early-morning women’s hour. I rolled myself in a gingham blanket and listened in the fetal position. The songs landed differently this time. WASP-y as they were, the women of country music were not the repressed type of angry. They slugged their cheating boyfriends’ headlights with baseball bats. Their abusive exes were stalking them, so they went home and loaded their shotguns.

After the hour had passed I was sure I knew these women. For one, I knew they were scared.

“Good evening, everyone,” Sylvie said. It was the middle of the day, and this was our first real band practice. We’d opened the garage door, tuned our instruments, mic checked, and everything. “This song is called the ‘Hava Nagila.’” Dalia and I looked at each other, then at Sylvie. One, two, three, four, Sylvie mouthed.

I hadn’t known that it was possible to slow a wedding song to something so eerie and absent of joy. Dalia squeaked her way through it, wincing as though each bow stroke pained her. I ran through the same four-chord progression over and over and was proud of myself for doing it so cleanly. My callouses were back, my finger pads no longer soft.

The song did not showcase Sylvie’s range in the slightest. Still, she nailed the gravelly tone she was going for, her voice haunting in its low vibrato.

“Okay, Johnny Cash!” Dalia said when we finished.

Sylvie grinned, piled her hair into a bun on top of her head. “I think we’re onto something.”

“What exactly,” I began carefully, “would you say we’re onto?”

“We’re original!” Sylvie said, basically shouting.

“We’re gimmicky. None of us are even that religious.”

Dalia stared at us, holding her bow with her arm slack. She reminded me of a lazy fairy godmother. I widened my eyes at her, silently begging her to defend me.

“More people than just Jews should get lifted up on chairs,” Dalia offered, suddenly passionate. “We’d be doing the world a service.”

“I’m not worried about doing the world a service. I’m worried about being dishonest,” I said.

“Since when are you taking this so seriously?” Dalia asked.

“Rachael wants everything to be a poem,” Sylvie said. Dalia laughed, and I hated her for that. I hated them both.

“Forget it.” I snapped my guitar case closed and stomped inside, letting the door slam behind me. From my room, I could hear the whine of Dalia’s violin as Sylvie led them through a throaty rendition of “Shabbat Shalom,” the entire song a repetition of those two words. I starfished onto my bed and started touching myself, picturing Benji’s face, his nubby ponytail peeking out from above the strap of his visor. Then the visor became a wide-brimmed hat and Benji’s cheeks went concave. I stopped masturbating and pulled the covers over my head.

“I don’t mean to be a dick,” Benji said, “but could you go a little faster?”

With my mayonnaise scooper in hand, I flicked my wrist, using the spatula to smooth the glistening lump across the bread before I shoved the sandwich down the assembly line to Benji.

“Number four,” I said. “And no.”

We were in the middle of a lunch rush, worse than usual. A line leaked out the door and into the parking lot; every seat inside was taken. Outside, families lingered at plastic picnic tables, which were bolted to the sidewalk, candy-striped umbrellas sprouting from their centers. A girl in a bikini top and jean shorts mumbled her order, her chest dusted with sand.

“What?” my manager asked her for the third time. I could tell he was two inches from losing it right there at the register.

“This is the shit I won’t miss,” Benji said. He rolled a sandwich in parchment paper, stickered it, then yelled, “Dave!”

I turned to him, a delivery ticket crumpled in my hand. My head pulsed with the drone of customer voices, the sound of collective dissatisfaction. “You’re leaving?”

“I put in my two weeks a couple of days ago,” he said without looking up. He pressed four provolone slices together, then slathered them in mustard. “A buddy of mine is working for this meat and seafood company where all you have to do is get people to sign up for a co-op membership, then boom.” He peeled off his gloves, which were coated in meat juice, then snagged a new pair from a box in the cabinet below us. “Money.”

I told him it sounded like a pyramid scheme. He said I was too young to know anything. Sometimes I forgot Benji was Sylvie’s age because I felt a lot older than him. Marco placed a hand on my arm. I jumped. A stack of order tickets had piled up next to me.

“Freezer, baby,” Marco whispered.

By the time I stepped out of the walk-in shivering, the crowd had thinned. Benji was on the register now. Briefly, he glanced at me before continuing to snap the band of his glove, a red splotch blooming at his wrist.

“I’ve always hoped you’d do something,” I said finally, my words slicing through the whir of the vent above us. “About the Fedora Man.”

“Tell him off. Kick his shins. I don’t know.” I rested my elbows on the steel island. Marco was next to me, working the meat slicer like an erg.

What I didn’t tell Benji was this: Anything would have been enough.

“I’m just trying to make it through my shifts,” he said. “Same as you.”

For the rest of the day, Benji and I tried to avoid one another, magnets lined up at identical poles. We stayed at least one person away from each other every time we were on the assembly line. He fielded calls and handed the delivery tickets to anyone but me.

My mother picked me up from work that day. She wrote for the local newspaper’s police beat in an office just minutes away. She had a police scanner in her car. The low rumble of staticky voices on the emergency channel always filled me with dread.

I slumped into the passenger seat and peeled off my visor, massaging my temples in circles. In the rearview, I caught a glimpse of a black Honda Civic, the same car the Fedora Man drove. We made a right out of the parking lot and the Civic followed. A pickup truck merged into the space between us, so I couldn’t see the driver, couldn’t know for sure.

“Rough day?” my mother asked. I was turned all the way around at this point, squinting out the back window, which was coated in a dusty film.

Two-thousand-ten Ford Escape, not registered to him, came the mumble over the radio. Suspect in the stabbing of a woman in the lot across from Dogwood Park.

“Can you please turn this off?”

“That bad, huh?” My mother lowered the volume only slightly, then sped through a yellow light. The truck behind us lurched to a stop.

Last seen westbound on U.S. Highway six. Unknown weapons.

“Hey!” she said. “I was listening to that.”

I stared out the windshield, tried to slow my breathing as the houses became more scattered. Striped with mower marks, fields unfolded before us, green and green and green.

I started to take my father’s truck on nights when I couldn’t sleep, winding my way along pothole-strewn county roads, always a sudden dip before the impact sent me up, my head centimeters from the ceiling liner, which was as gray and pocked as the ground beneath me. Windows down, country station blaring, my hair whipped around my face to the twang of the guitar, to lyrics about hell and high heels and heartbreak and revenge, always revenge. The way the stars splattered across the sky reminded me of a video Sylvie showed me once, of someone sneezing under a blacklight. I slammed the brakes at every stop sign, in love with the feeling of falling forward and being caught.

In Boone Grove, we had a post office, a fire department, an auto parts store called Rusted Knuckles, and an enormous white church off of 550, which hosted an annual antique car and tractor show in the parking lot. Often my drives led me to that parking lot, Carrie, Reba, and Faith guiding me through night’s blank expanse as they proclaimed their mellifluous devotion to Jesus through the truck’s speakers.

One night, I examined the church in my headlights, thinking how it was boxier than the churches I’d seen in my European history textbook, whose peaks appeared as though they might puncture clouds. The placement of the windows created the illusion of a wide, cartoonish face, the door its screaming mouth.

I stared at the massive black cross on the front of the building, which stopped right above the door frame. If this were a conversion story, I would’ve gone in, gotten on my knees in front of the crucifix, and touched Jesus under the loin cloth.

Instead, I let the truck idle. I slapped the dome lights and pulled my notebook into my lap, which I usually saved for when I wanted to consider the girthy possibilities of the caveman’s manhood, or how I was jealous that my sister got to be the angry one.

Sylvie, who tore through life phases at lightning speed, had hit her rebellious streak around twelve. Her first-floor bedroom allowed her to drop right out of the window and onto the ground. I remember watching overhead as she untangled herself from the bushes, her spindly silhouette racing into the night, fast on her way toward God-knows-where. She chugged my father’s 3 Floyds, tossing cans into the trash haphazardly. She chain-smoked menthols while Hebrew school was in session, lying with her legs up the seatback of the bathroom’s dusty plaid armchair such that she could blow smoke directly up at the detector, as though tempting a higher power. And strike her down He did—well, “she” in this case, the rabbi administering a suspension after Sylvie finally set off the alarm. I could hear my parents hiss her name through the wall at night, strategizing in hushed voices. Sylvie had grown out of it on her own but kept her mercurial edges. So far, I’d kept my ability not to make things worse.

I stayed in the church parking lot until I’d written a song, six pages of scratch paper balled beneath the driver’s seat. I called it “Amen, I Win” because it was about fighting God outside a Burger King and had lines like “Couldn’t even take a hit / He owes me French fries and my wits.” I was sixteen and thought I was onto something. The world hadn’t squeezed the earnestness all the way out of me yet.

The next morning, my father noticed his gas light was on and I got grounded for a week, no longer allowed to leave the house except for work, which was fine. Besides in the dead of night, I’d stopped going anywhere anyway.

Since Sylvie was leaving for Ball State in a few weeks, she’d been picking up extra shifts at Little Caesar’s. I hadn’t seen her much in the days since our argument, but when I pressed an ear to my bedroom floor I could hear her singing downstairs, her shaky contralto somehow delicate. It sounded to me like she was digging for something, reaching for the bottom of a well that just wouldn’t end. Listening to her croon like that alone in her room gave me a heavy feeling, but I stayed wide awake.

A couple of mornings after I’d been grounded, Sylvie and I both had the day off work. When I woke up she was already in the kitchen, slurping sweet milk from her bowl of Golden Grahams. I fixed myself peanut butter toast, peeled off the crusts, and dangled the brown strands in front of Sylvie. She snatched them, balling the crusts between her palms before shoving them into her mouth.

“Dalia’s coming to practice a few songs today,” Sylvie said between chews. “If you want to join.”

I tried to shake the hurt that they’d coordinated without me by thinking about the sadness of Sylvie’s voice in the nighttime.

I grabbed my notebook and flipped to it, my handwriting slanted and spidery. As Sylvie read, I bounced my knee. I could tell she was pinching back a smile because a couple of snorts came out while her mouth stayed pulled into a line.

“This could work,” she said. She shoved the notebook back across the table. I seized it quickly, nervous the pages might flutter and she’d see something I’d written about her, that we might slide backward on our journey to mending our unspoken weirdness before she moved to Muncie.

Dalia arrived a couple of hours later, this time with her father’s tambourine and a harmonica she’d discovered in an antique store, which struck me as hygienically risky, though it worked like new. She found Sylvie and me crouched out back by the barbed wire fence, wrenching weeds from the earth and tossing them into a pile.

“Watch this,” Dalia said. With the sun behind her head, she fluttered her hands against the harmonica. The sound warped and wavered; the moment went fragile. If Sylvie and I had moved, we might’ve poked a hole in it.

When Dalia finished, we gave a standing ovation. “I didn’t know this about you,” I said. Sylvie laughed and shook her head. Her wispy bangs bounced.

“I’d sort of forgotten about it too.” Dalia passed the harmonica between her hands, re-memorizing its weight.

Sylvie sang my song for Dalia, and Dalia cackled through it. She sang it again, then again, trying on tempos and keys. Eventually, Dalia joined in on the harmonica. I started strumming—mindlessly at first, wanting to linger in the moment, a moment where my sister was taking my words seriously. My fingers found a chord progression that stuck, and soon my song was alive—my sad, Jewish fight song. I hoped God was listening.

When I finally became un-grounded, I gave myself permission to start taking the truck again, so long as I drove straight to the church and didn’t idle long enough to tip the fuel gauge into suspicious territory. The rules I’d laid for myself gave my songwriting a new urgency. In my lyrics a girl sculpted a golem from mud and sent it after her enemies. In another song a girl sat in the freezer at work, reciting the Shema, until one day she decided not to hide anymore, reaching over the register to deck her stalker.

“Is this about you?” Sylvie asked, lowering the page.

“That’s not how you’re supposed to read the work of a songwriting maestro,” I replied. “Did Bob Dylan have to answer to the question of autobiography?”

“Possibly not.” I didn’t know, either.

We set up in the garage again, found time for a routine we could commit to almost nightly—Dalia slapping her tambourine, Sylvie belting my angry lyrics at a newly upbeat tempo, me training my fingers to hold their arches as the sunset bled across the sky. Facing the dirt road that led to our tiny corner of the universe, I felt achingly aware that this was not a place people came back to, that once Sylvie was gone, she was gone for good, this map dot just a funny origin story.

“From where you came the earth was wet / Go get ’em now, go make ’em sweat,” Sylvie sang. She sang it with her whole face—eyes squeezed shut, mouth so open I could see inside of it.

I turned and sprinted to the freezer, pushing past my new coworkers, their faces smeared with confusion.

We started to call ourselves the Ugly Sisters. The joke was that none of us were ugly and not all of us were sisters. Dalia’s brother worked at Cliffy’s, an old dive bar by the train tracks, and he was able to book us a Sunday night gig.

“Is it still a gig if we’re doing it for free?” I asked.

“Shut up,” Sylvie said.

We were nervous and sweaty about it, but mostly we were excited. Our band practices stretched into the wee hours, the crickets chirping their backup vocals.

Indiana law prohibited us from even entering the bar until we turned twenty-one, but Cliffy’s was not the kind of place to give a shit. The walls looked like floorboards and were covered with tacky aluminum signs that said things like LAST DANCE WITH MARY JANE and EVERYTHING IS FINE. As we climbed the stairs to the second floor, I hugged my guitar case and trembled a little. But the crowd ended up being tiny—a group of lanky guys in oversized t-shirts and a couple of old ladies gossiping in whispers.

“I thought there would be more people,” Sylvie whispered as she adjusted the mic stand. Realizing this audience would have made its way to Cliffy’s tonight with or without the promise of live music, my nerves ebbed slightly.

“Hey, everybody,” Sylvie said into the mic this time, her voice deep and smooth. She wore knee-high boots and a striped dress that hung loose around her shoulders. A couple of people clapped. “We’re called the Ugly Sisters.”

We began with my freezer song, arguably our most serious. The melancholy of Dalia’s harmonica, combined with the lyrics themselves—“I hide from you ’cause I’m afraid / You’re fifty and I’m in tenth grade”—left the room in an unsettling silence. Dalia’s brother cheered from behind the bar when we finished, probably out of pity. I felt sorry to bother everyone with my suffering.

But by the time we were halfway through “Amen, I Win,” the energy shifted, our audience relaxing into lyrics they knew they could laugh at. At the end of the song, a drunk guy stood up and punched the air. A woman whistled with her fingers in her mouth.

Buoyed by their approval, we floated through the rest of the set in a trance, Sylvie working the audience with her mellow voice and comic timing, Dalia and I riding her coattails. No one lifted anyone on a chair, but we all walked out buzzing.

A few nights before she was set to leave for Muncie, Sylvie walked into my bedroom while I was changing.

“Would it kill you to knock?” I threw on my softest t-shirt, which came down past my underwear, then lay across the width of my bed, my hair fanning out like a wreath.

“Oh, you’ll miss me,” she said. My mattress creaked as she fell onto it, belly-first.

“Never said I wouldn’t.”

“I’ve been thinking about our music, how we’ll probably stop forever if I go to college.” She sounded congested. She turned to me, puffy-eyed.

“What do you mean, if?”

“I think we should focus on the band. We could be smart about it, really commit ourselves and build a following before we take it on the road. What do you think? Actually, we should call Dalia—”

I softened my voice. “We’re not that good, Sylvie.”

“I thought you believed in us.”

I propped myself on my elbows. It didn’t feel right, big-sistering her. “It’s something we did for fun.”

“Maybe I don’t want to do things not-for-fun.”

“If you don’t go to college, and music backfires, would you want to stay in Boone Grove?”

Her gaze shot toward the ceiling stain as she thought about it, which made me feel more related to her than usual. “No.”

“Then get out of here,” I said.

Three days later my father pulled out of our garage and turned onto the dirt road with Sylvie in the passenger seat. He’d used bungee cords to secure her belongings to the truck bed, and her mic stand poked through the mess like a spear.

There’s still time, I thought about saying. We could call Dalia, we could take it on the road.

My next shift at Jimmy John’s began the same as all the others. I punched in my ID number, Velcroed my visor around my head, and pulled my ponytail over the strap. No one was on the register, so I stood behind it and drummed my fingers at the edge of the cash drawer. Benji was gone, probably messaging Facebook friends from his parents’ basement with reasons why they specifically should sign up for a meat and seafood co-op membership. My manager had moved to Kokomo with his wife, and Marco had picked up a part-time job at the sawmill, slicing his JJ’s hours in half. I didn’t know today’s crew well at all, and they didn’t seem to know each other. The AC had broken the night before. We rubbed our faces on our t-shirt sleeves. It was a quiet morning, disrupted momentarily by the bleating oven timer. Out came the hoagies, hot and fresh. Or just no longer frozen.

Customers jangled on their way in and out—bells chimed, bracelets clacked, change clinked into the tip jar. I was in a chatty mood thanks to my new status as an only child. I asked little kids their favorite colors and gave an elderly couple my last two sticks of gum. The change kept coming.

I saw the Fedora Man see me as soon as he opened the door. I searched the faces in the kitchen for some flicker of awareness. My new manager moved toward me on his way out of the freezer, carrying a block of turkey, cold vapor encircling him. He had the meat cradled in his arms as though it were a baby he’d saved from a burning building. I snapped back around to meet the Fedora Man’s eyes, strikingly blue behind thick-framed glasses. He had his wallet open, and in the ID window I saw a photo of myself in my Jimmy John’s uniform, eating a sandwich.

“Where have they been hiding you, beautiful?” He leaned in like he thought he might find the answer in the details of my face, and as he ordered I felt every warm syllable of tomato against my nose. Then he pulled a pink handkerchief from his pocket and ran it along my sweaty forehead—slowly, which was the worst part I think, the imagined romance of it all. I considered swiping his fedora. Without it he might have been just a man, a man with an aversion to tomatoes. But I didn’t have a baseball bat, much less a shotgun. No one was going to save me.

I turned and sprinted to the freezer, pushing past my new coworkers, their faces smeared with confusion. Once inside, I stretched out on my back, the cold of the aluminum panels the first familiar sensation in days.

I stayed like that for an hour at least. At one point my manager opened the freezer, saw me lying there, then let the door fall shut. No one bothered me other than that.

When I found the will to stand, I looked around for something to break, but everything was too sharp, too metallic. I picked up a box of hoagies, ripped off the packing tape, and turned it upside down. The frozen breads thundered against the aluminum. I stared at the pile of them. Not quite satisfied, I picked one up, gripped it with both hands, and whacked it against a shelf until it split into two.

Only three of my coworkers remained in the kitchen when I emerged from the freezer. The sign on the door had been flipped to CLOSED and my new manager was sweeping up some shredded lettuce. He nodded when he saw me. “Hope you got some rest in.” Then he held out the broom. “I’ve got to make a couple of calls.”

I ripped my visor from my head. “I quit,” I said. I tried to use the mayonnaise-flick of my wrist to toss the visor like a Frisbee, but it barely cleared the plexiglass. The man mopping near the entrance paused to glare at me.

I had thought it would be more exciting, that someone would yell or chase me out the door. But my new manager just said, “Your final paycheck will be available on Tuesday.”

That night, I called Sylvie. We talked about Muncie and the colorful storefronts along the downtown strip, how stoplights reached like arms into the road. I could hear her crunching on chips as she spoke. Her roommate, who had just broken up with her high school boyfriend, wept intermittently in the background.

“Reba McEntire and her husband just announced their separation,” I said.

“Oh, wow. Not a great summer for the country music girls.”

“He was her manager too, so I wonder what she’ll do now.”

“Yeah, well.” Sylvie paused. “I guess I haven’t been paying attention to that stuff.”

I stared at my guitar, which I’d leaned against the washing machine, wondered how long it would be before it started gathering dust. There’s still time, I thought about saying. We could call Dalia, we could take it on the road. But then the roommate’s sobs began to crescendo.

“Shhhhh,” Sylvie said. “You’re going to be fine.” I pretended she was talking to me.