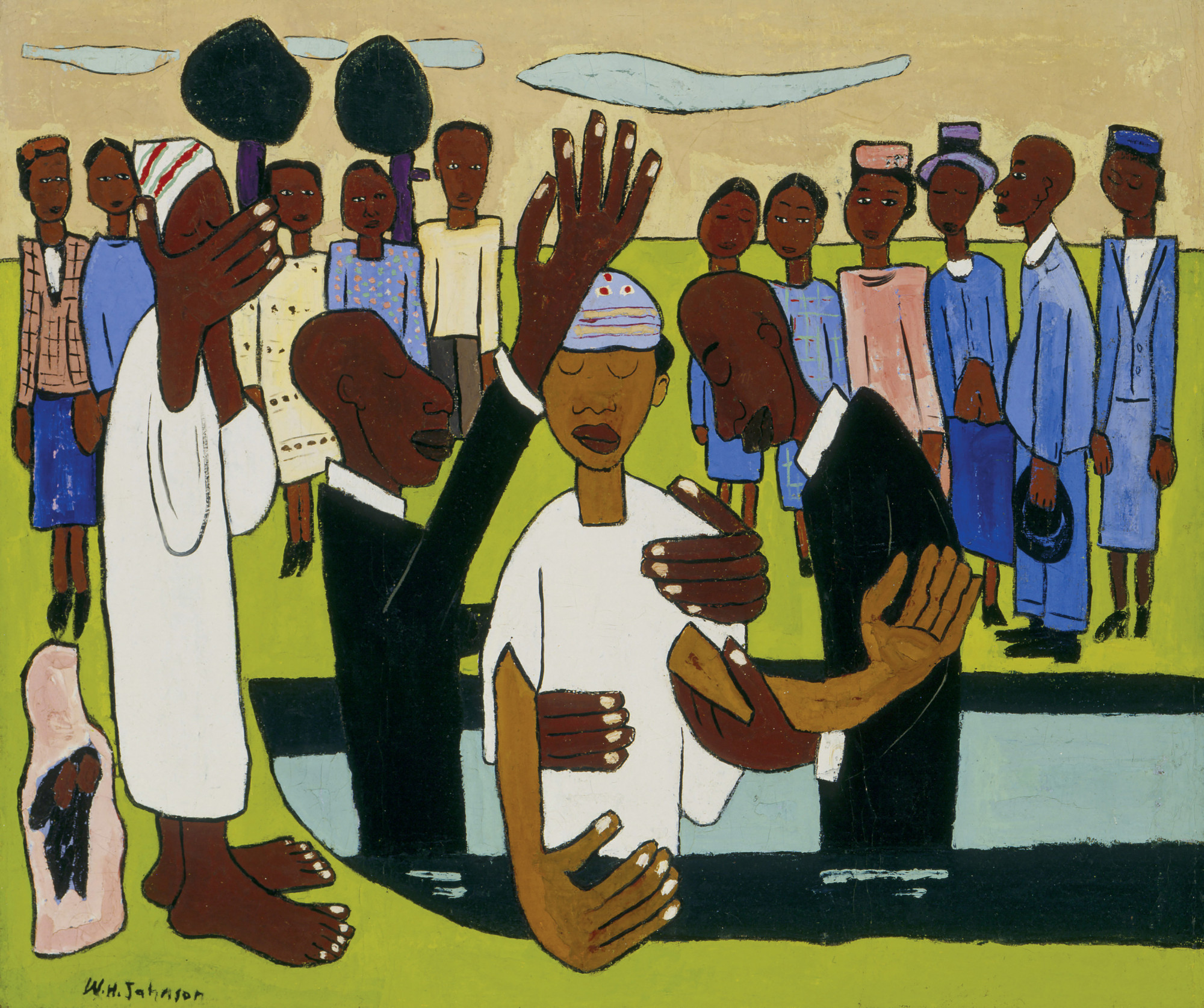

I Baptize Thee, ca. 1940, oil on burlap by William H. Johnson © The artist. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, D.C./Art Resource, NY

How Memphis Gave Gospel the Holy Ghost

Chicago gave it form; Detroit gave it choirs; Philly gave it showmanship—but Memphis gave it Soul

By Robert F. Darden

On the evening of October 7, 1952, gospel promoters booked the Spirit of Memphis for a concert in Memphis’s Mason Temple. The lone known recording from that evening is the two-part 45 record, “Lord Jesus, Part 1 and 2” (King 4576). While the composition is credited to Wynona Carr, “Lord Jesus” isn’t really a song; it’s more of an extended prayer chant, with quartet leader Jethro Bledsoe shouting over the group, which harmonizes wordlessly behind him in what author Opal Louis Nations calls an “old church moan.” The track begins abruptly, as if the engineer has suddenly decided to turn on the tape recorder, so we don’t know how long the song has already been going on. The congregation at Mason Temple knows, though—they’re already deeply, intimately involved.

Side 1 of “Lord Jesus” is punctuated with voiceless shouts and exclamations from the crowd, pushing, urging Bledsoe onward as the quartet centers its harmony on an eerie E dominant 7th drone (or pedal point) chord. At about the one-minute mark, he slips into a remarkable glissando. At about the 1:30 mark, Bledsoe erupts into a sharp, spooky bark of laughter. As the background shrieks and wails continue, the other members of the Spirit of Memphis somehow resolve into a single chanted, harmonized word—“Jesus”—even as Bledsoe continues to shout, testify, and beseech the Holy Spirit. The vamp continues on Side 2, raging on with more of the same until the fade.

I can’t remember a time when I wasn’t passionate about gospel music. Since I got into academia, that’s all I’ve researched and written about. Nearly twenty years ago, concerned about the accelerating disappearance of vinyl from gospel’s “golden age,” I co-founded the Black Gospel Music Preservation Program at Baylor University. Among the more than 50,000 digitized holdings of the BGMPP, there is simply nothing else like “Lord Jesus.” During the 45’s 6:24 total run time, ethnomusicologist Kip Lornell says that Steele employs “melismatic, falsetto, and sforzando vocal techniques” and that the song “literally pulsates with a fervor that would have been impossible to replicate in a studio.” Historian Horace Boyer adds, “The delight at this exchange is apparent from the shouts, encouragements, and screams of the audience…providing an indication of the kind of ecstasy apparent at live performances of beloved gospel groups.” This is clearly not entertainment. Composer Stephen Newby calls it “an engagement with the Holy Spirit, fueled by Bledsoe’s otherworldly prayers on the congregation’s behalf.”

Listening to that song on repeat has led me to make a series of sweeping generalizations:

Chicago, through Thomas Dorsey, by way of Charles Tindley and Lucie Campbell, gave modern gospel music its form, both in performance and—soon thereafter—on vinyl.

Detroit, through Mattie Moss Clark, gave gospel its choirs.

Philadelphia, through the Dixie Hummingbirds and the Clara Ward Singers, gave gospel its showmanship.

But it was Memphis, through the Church of God in Christ and East Trigg Ave. Baptist Church, that gave gospel music the ecstatic spirit—the Holy Ghost. Of course, in evangelical Protestant religious music, the supposition is that the Holy Spirit has always been present in sacred music. But it was the churches, denominations, and artists themselves of Memphis that were the catalyst for the Holy Ghost to dramatically manifest through twentieth-century gospel music, both in worship services and, occasionally, on a recording.

In the Stax Museum of American Soul Music, one of the first exhibits visitors encounter claims that the Stax studio was the result of the “Three Rs—Race, River, and Religion.” But that can also be said more generally of the city of Memphis itself and its utterly original place in American musical history.

Of those Three Rs, Memphis is Memphis, in part, because it is a unique transportation hub (and under “River” I’ll include “Roads and Railroads”). If you drive into Memphis on Interstate 40 from the west, just past the massive chocolate ribbon that is the Mississippi River, you pass by St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, thrice-blessed for its unrelenting war on childhood cancers. From the south, Interstate 55 barrels up from Mississippi, right into the heart of the city.

But if you drive up from the south on old Highway 61, particularly at dusk, you’re traveling in the footsteps of a million African Americans on the Great Migration. The new Highway 61 will take you straight downtown. Along the way, you’ll cross in short order the streets that are home to several of the spiritual centers that help define the city: East Trigg Ave. (home of East Trigg Ave. Baptist Church), Lucy Ave. (birthplace of Aretha Franklin), East McLemore Ave. (home of the Stax Museum of American Soul Music), and if you look to the east, just north of Walker Ave., you might just see the top of Mason Temple, a three-story edifice that serves as the headquarters for the Church of God in Christ.

Mason Temple is the Mecca of the Church of God in Christ, better known by its acronym, COGIC. It even has its own hajj—the annual Holy Convocation—most recently held in early November 2024. Mason Temple is the spiritual home of the denomination’s millions of members, spread across about 12,000 churches in 112 countries.

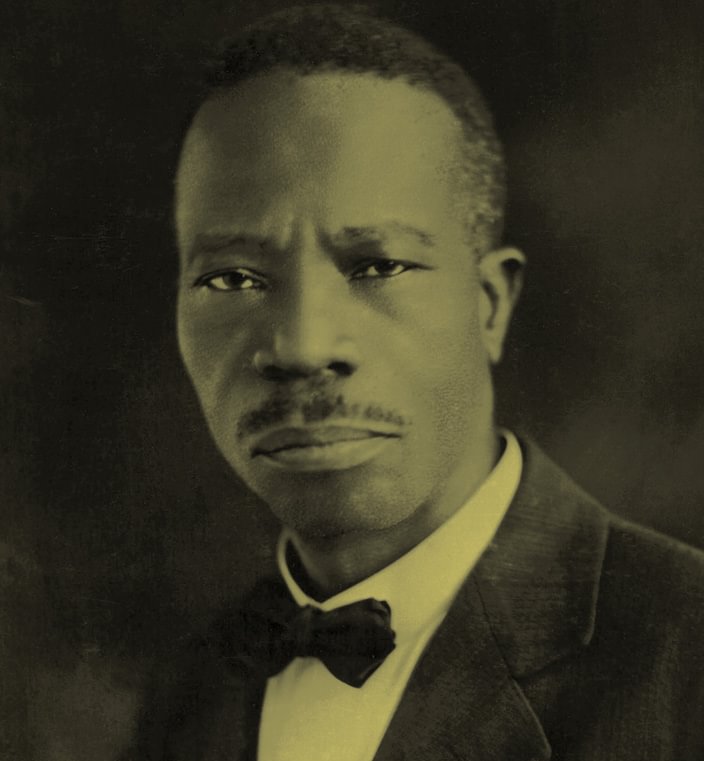

Mason Temple is COGIC founder Charles Harrison Mason’s vision. In 1907, deeply disillusioned with what he saw and heard in mainstream Black churches, he traveled to hear speakers at what was already being called the Azusa Street Revival, off a sleepy side street in Los Angeles. Once there, Mason experienced what participants called “baptism in the Holy Spirit.” The revival at humble Azusa Street remains one of the most significant such religious events in the twentieth century, a nearly unparalleled explosion of a doctrine that emphasized highly emotional services, speaking in tongues, prophecy, healing and other “gifts” of the Holy Spirit, and an intensely personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

Led by African American preacher William J. Seymour, several major denominations emerged from the movement, including the Assemblies of God, the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel, and the various Holiness and Pentecostal denominations. All differed dramatically from the largest African American denominations, Baptist, Methodist, and African Methodist Episcopal, which at the time resembled their white counterparts in decorum and doctrine, and also in a restrained musical presentation, usually accompanied only by piano or organ. Thrilled by what he experienced, and filled with a holy fervor, Mason returned home to Memphis where he prophesied, saw visions, preached an all-inclusive doctrine, and established his first church off Beale Street. Among the poor and dispossessed, many recent arrivals from the increasingly mechanized cotton fields of Mississippi, he founded what would become one of the largest African American denominations in the world.

Bishop Charles Harrison Mason. Photograph courtesy Church of God in Christ

Women attendees of the 46th convocation of the Church of God in Christ, Mason Temple, Memphis, TN, November 25–December 15, 1953. “Photo by R. Earl Williams, 567 Beale Ave., studio 37-5022, res. 8-1073, Memphis, Tenn.”—stamped on back. Courtesy the Center for African American Church History and Research, Inc., and Glenda Williams Goodson

COGIC worship services are characterized by a joyful, spirit-fueled abandon, where pastors emphatically exhort or “invite” the Holy Spirit to join the services. Gospel music, as Horace Boyer writes, was the “illuminating force behind this theology.” By the 1930s, even existing hymns were “gospelized” and COGIC church services “were nothing less than ecstatic, with forceful and jubilant singing, dramatic testimonies, hand clapping, foot stomping and beating of drums, tambourines and triangles (and pots and pans and washboards when professional instruments were not available).” Even when pianos could be “begged, borrowed or bought,” Boyer writes, “a barrelhouse accompaniment served to bring the spirit to earth.” Older, slower, sometimes dirge-like hymns beloved by older Black denominations simply did not fit the needs of these new congregations. Members of other churches, hungry for this kind of spirit-filled music and preaching, soon began attending COGIC services as well. In short, the beloved verse that declared “make a joyful noise unto the Lord” didn’t exclude any musical instrument—even guitars and drums. Boyer’s brother James, also a historian, posits that the close proximity to Beale Street meant that many of the early converts were already intimately acquainted with the beat of the blues and (later) rhythm & blues. It was not the instruments that were sinful, COGICs believed, rather the men (and occasionally women) who played them. Mason also spontaneously composed numerous up-tempo, high-energy songs, also called “chants,” including several (“I’m a Soldier in the Army of the Lord” and “Yes, Lord,” among others) that are still performed today.

The denomination’s emphasis on musical evangelism meant that a startling array of uncommonly talented musical evangelists spread out across the country in the decades that followed. Known as “planters,” these musicians were tasked with establishing new congregations. James Boyer has identified (among others): Ernestine B. Washington (1943), Marion Williams (with the Ward Singers, 1940s), Marie Knight (1940s and ’50s), the Boyer Brothers (1951), the Gay Sisters (1951), Kitty Parham (1953), Charles Taylor Singers (1954), Cassietta George and Gloria Griffin (mid-1950s), and the O’Neal Twins (1962). Other well-known COGIC gospel artists include Mattie Moss Clark; the Clark Sisters; Myrna Summers; Timothy Wright; Walter, Edwin, and Tramaine Hawkins; and Andraé Crouch.

In the early 1920s, Mason sent out two extraordinarily talented young women as planters: Blind Arizona Dranes of Texas and Sister Rosetta Tharpe of Arkansas. Their work is still hugely influential in gospel music—Dranes for her pumping piano stylings and Tharpe as gospel’s first “cross-over” artist, who popularized swinging versions of both old spirituals and Thomas Dorsey’s new gospel songs. While Tharpe’s career has started to be chronicled and celebrated in recent years, less is known of Dranes and her unique “choral style” of piano accompaniment. In 2003, writer Michael Corcoran interviewed a ninety-year-old woman who vividly remembered Dranes in performance: “She’d get the whole place shouting. She was a blind lady, see, and she’d let the spirit overtake her. She’d jump from that piano bench when [the spirit] hit her.” Corcoran describes her as the Holy Ghost’s “favorite” singer.

That’s not to say that Mahalia Jackson or groups like the Golden Gate Quartet or the Roberta Martin Singers were not emotional. Jackson occasionally performed a sanctified shuffle, but she was careful to never let her feet leave the floor. She had, after all, listened as a child outside a Pentecostal church near her home in New Orleans. But in the throes of the spirit, there was no telling what a COGIC artist would do. According to Horace Boyer, “Pentecostal/Holiness singers sang with more passion, seeming abandon, and consequently more improvisation than was sanctioned in the Baptist and Methodist churches.” It wasn’t long before even the most straitlaced, flat-footed gospel a cappella group was inexorably drawn to the more ecstatic expression of the COGIC artists. This “heated exchange” between gospel artist and congregation was called, as Kip Lornell writes, “getting happy” or, more tellingly, “feeling the spirit.” Certainly not all congregations were comfortable with the COGIC style, but most gospel music audiences cheerfully embraced it.

Sister Rosetta Tharpe performing in an MGM studio, 1961 © Everett Collection/Alamy

Rare photograph of Blind Arizona Dranes. Rights unknown

At 7,500 seats, the art moderne Mason Temple, the cornerstone of the seven-building COGIC headquarters complex, was one of the few venues in Memphis large enough to accommodate denominational convocations, multi-artist gospel “extravaganzas,” and national speakers, including Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Built in 1940, the three-story building once included a nursery, salon, photographic booth, first aid and emergency ward, post office, and even a baggage-check room.

Today, Mason Temple is a stop on Memphis’s Civil Rights tours. Inside, flags representing every country with a COGIC church enliven the expansive sanctuary. Mason himself is entombed there. On April 3, 1968, King delivered his extraordinary, largely improvised “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” sermon there.

Before traveling to Memphis recently, I listened to “Mountaintop” again and again. I was repeatedly struck—or maybe a little awestruck—by the sheer musicality of the words and declamation, how often King alludes to spirituals and hymns, and especially how the tone shifts so dramatically in the final sentences. The evening of April 3 was stormy, and King was fighting a cold and exhaustion; he hadn’t originally even been scheduled to speak that night. But with the words, “I don’t know what will happen now. We’ve got some difficult days ahead. But it doesn’t matter with me now…,” his world-weary voice suddenly tingles with an otherworldly crackle. It’s the Prophetic Voice, the voice of the Holy Spirit speaking through him. His final words quote a line from a beloved hymn, “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” “Mine eyes have seen the glory!” Those who were in attendance that night must have remarked, even then, that something had happened. This was not King’s standard “stump” sermon—his entire demeanor changed. In Mason Temple, the Holy Ghost yet again suffused the man and the moment.

Memphis has, it seems to me, an uncanny ability to do that.

Besides Mason Temple, the other most significant religious structure in Memphis, at least as it relates to gospel music, is East Trigg Ave. Baptist Church, home church of the man who historian Anthony Heilbut calls a “magnificent songwriter,” the Reverend William Herbert Brewster. The son of sharecroppers, Brewster came to East Trigg in 1930 and built it—and the adjoining seminary where he trained ministers, including Rev. C. L. Franklin—into an absolute national powerhouse. The original building at 1189 East Trigg still stands, though the congregation eventually moved to a larger sanctuary around the corner. It’s difficult to imagine now, but this small, shuttered church building is where the first two million-selling gospel songs, “Move on Up a Little Higher” by Mahalia Jackson and “Surely God Is Able” by the Ward Singers, were first composed, performed, and packaged to profoundly change gospel music forever.

Brewster’s literate, biblically based compositions were among the very first to consciously include a closing vamp, that repetitive, riff-based conclusion now found in so many gospel songs. In doing so, Brewster captured and gave his blessing to what COGIC artists had spontaneously been doing for years. The vamp is wholly given over to musical improvisation and spontaneous ecstatic utterances. In the right circumstances, such as the last song of an evening, the vamp—which can last many times longer than the original composition—becomes something more than a gospel song. Stephen Newby says the origins of funk music can be found here, where both artist and listener become lost in a celebratory holy dance, just as participants describe their experiences in a rave. It has all of the hallmarks of a possession.

How did the Baptist-ordained Brewster come to popularize what Heilbut calls “a seamless blend of Baptist and Methodist decorum and sanctified ecstasy”? Writer William Ellis suggests that Brewster “not only came under the spell of W.C. Handy but was exposed to the charismatic, emotive expressionism of Pentecostalism.” By the late 1940s and into the ’50s, every gospel artist, including the Soul Stirrers, Aretha Franklin, Marion Williams, the Blind Boys of Alabama, the Swan Silvertones, Sam Cooke, and more, clamored for Brewster songs—“Packing Up,” “Lord, I’ve Tried,” “How Far Am I from Canaan,” “Weeping May Endure for a Night,” “These Are They,” “I’m Getting Nearer My Home,” “How I Got Over,” and nearly 200 others. The Ward Singers recorded so many of Brewster’s compositions that they established a publishing house for them. Heilbut even dubbed the Ward Singers’ version of “Surely God Is Able” as the “biggest shout number of all time.”

Brewster’s influence reached further still. He hosted two regular radio programs, Gospel Treasure Hour on the famed WDIA in the mornings and Camp Meeting of the Air in the evenings on WHBQ, which was broadcast live from East Trigg and—shockingly for its time—attracted a large multi-racial audience both over the airwaves and in person, including a shy young man named Elvis Aron Presley, who regularly sat in the back.

Thanks in part to the research of Kip Lornell, the influence of the community-minded WDIA, which billed itself as the “First—and only 50,000-watt station programmed exclusively for Negroes,” has been extensively documented. By 1949, it was the first station in the United States with exclusively African American DJs. WDIA raised money for African American charities and schools, hosted civic-minded events and concerts, sponsored fundraisers for emergencies, built baseball fields, and bought buses to transport children with disabilities.

Brewster especially championed numerous Memphis-based artists on the show Gospel Treasure Hour, including his own Brewsteraires and the Brewster Singers, which featured Cassietta George and the incomparable Queen Anderson. Because the Bluff City’s blues and gospel roots run so deep, Brewster was able to draw from a fathomless well of talent on his program. The first recorded Memphis group was the I.C. (Illinois Central) Glee Club, who—hired by the railroad—rode the trains and entertained passengers with a cappella renditions of old spirituals and pseudo-spirituals. Other notable Memphis quartets, though not all from the COGIC tradition, included the Southern Wonders, the Middle Baptist Quartet, the Dixie Nightingales, the Golden Stars, the Harps of Melody, the Gospel Writers, the Pattersonaires, the Songbirds of the South, the Sunset Travelers, and—most importantly—the Spirit of Memphis Quartet.

Ah, the Spirit of Memphis (they soon dropped the “Quartet”), gospel’s most dynamic all-star singing aggregation—only the Caravans could consistently compare with their array of talent. Lornell’s essential “Happy in the Service of the Lord”: African-American Sacred Vocal Harmony Quartets in Memphis name-checks all of the city’s most beloved quartets, but the focus is on the Spirit of Memphis (named for Charles Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis). The group first recorded in 1949 with a lineup that included co-leads Silas Steele and Jethroe Bledsoe, Earl Monroe (bass), and James Darling (baritone). The hits began almost immediately—“Happy in the Service of the Lord,” “On the Battlefield,” “Days Passed and Gone,” “Blessed Are the Dead,” “How Far I Am from Canaan,” “Automobile to Glory (1 and 2),” “Atomic Telephone,” and others—reliably keeping accountants happy at Syd Nathan’s Cincinnati-based King label, which released their music.

The personnel turnover continued and by 1952, in addition to Bledsoe, Steele, Howard, and Malone, the roster included the preternaturally high tenor of Wilbur “Little Axe” Brodnax, Robert Reed, and WDIA’s Theo “Bless My Bones” Wade, who served as the group’s live emcee, promoter, and booking agent, and hosted the daily 10 A.M. radio program on the station. Few quartets could match the Spirit of Memphis’s twin leads of Bledsoe and Steele, whose urgent, powerful vocals all but defined the “hard” gospel style popularized by COGIC quartets, in which one or two singers would take the lead vocals on the song, with the rest of the quartet backing them. Author Opal Louis Nations writes that they were “the leading and certainly most influential church-wrecking quartet” of gospel’s golden age, from 1945 to perhaps 1965, when gospel artists performed in virtually every town in America every Saturday or Sunday. On vinyl, the Spirit of Memphis’s energy still comes through, despite the often haphazard studio sessions they did for King, where the group would have to record an entire album’s worth of songs in a single day.

Reverend W. Herbert Brewster, Sr. (standing, rear) and Queen C. Anderson (third from right) at East Trigg Baptist Church, Memphis. Photograph by Ernest C. Withers © Dr. Ernest C. Withers, Sr. Courtesy the Withers Family Trust. Memphis Brooks Museum of Art purchase with funds provided by Ernest and Dorothy Withers, Panopticon Gallery, Inc., Waltham, MA, Landon and Carol Butler, The Deupree Family Foundation, and The Turley Foundation

That crackling energy is even more heightened on “Lord Jesus,” the 45 recorded live at Mason Temple in 1952. Nathan, whose King/Federal roster included James Brown as well as the Famous Flames, the Ink Spots, Hank Ballard & the Midnighters, Etta Jones, and dozens of other r&b, blues, and country artists, paid little attention to his gospel artists. But for some reason, on this date, he assigned a recording crew to capture the quartet’s Memphis concert. In 1952, live recordings were both technically challenging and expensive, and consequently exceedingly rare in gospel music. No one remembers why Nathan ordered one this time.

“Lord Jesus” caught fire and sold exceptionally well, sweeping the country and becoming one of the most influential gospel 45s of all time. After the release of “Lord Jesus,” Bledsoe told Lornell that once King Records “put that thing out…that record went out all over everywhere; we made all kinds of money and that’s the way we got to go on the road and make appearances. We would pack every auditorium everywhere.”

(The Spirit of Memphis, with an ever-changing lineup, continued to perform for decades. One member, Joe Hinton, had a short-lived pop music career, highlighted by his memorable performance of “Funny How Time Slips Away” that ends with one of the highest, scariest notes in the history of popular music: a stratospheric B-flat, one octave plus a minor 7th interval above middle C that would have been the perfect close to “Lord Jesus.”)

Still, Lornell’s comment that the spirit-filled trance-like experience of “Lord Jesus” could not have been replicated in the sterile confines of a studio troubled me. In most Christian faith traditions, the Holy Spirit pretty much goes wherever it wants to, whenever it wants to. When Newby and I interviewed singer Howard McCrary about his experiences recording vocals with Andraé Crouch, McCrary said that Crouch implored the Holy Spirit to enter the studio before each recording session:

When we sang it in the studio, the Holy Spirit came down on us. The Shekinah Glory was right there in the studio that day when we sang. We couldn’t stop crying, we couldn’t stop singing, we just kept singing over and over again, “Jesus, something about that name.”

There are, of course, dozens of recording studios in Memphis, most notably Stax Records and Sun Records. According to Memphis music historian Robert Gordon, perhaps even as essential as the sublime music they produced (and continue to produce), the importance of the studios is based on how they “generated human cultural collisions.” In those studios, Black and white musicians made universal music. Memphis music, he adds, “is a concept, not a sound.”

Through the Church of God in Christ and East Trigg Ave. Baptist Church and W. Herbert Brewster and the Spirit of Memphis and so many others, Memphis infused and empowered gospel music with the unconditional freedom of the Holy Ghost. After attending a service at Al Green’s Full Gospel Tabernacle, I finally managed to track down Bro. Al himself some days later for a phone interview for a Christian music magazine. After we’d talked for a while about his then-current album, Love Is Reality, the impact of the Holy Spirit on gospel music—naturally—came up:

Once on stage, I have no control. When I get that feeling, that anointing, that extra something, I can’t hold back. Once you’re up there in front of God and all those people, you get a sixth sense about things—you’ve got more than your regular five senses. You’re going to give it all you got. And when I finally have to say, “Good night, y’all,” it’s because that’s all I can do.

That’s the gift of the Holy Spirit to gospel. The freedom, the blessing to the gospel artist to give yourself wholly over to it—even if just for the vamp—and to bask in unbridled, unfettered joy.

That’s what makes gospel music at its best so sublime: To stand (or not) and sing (or not) in total transparency, enraptured in something or Someone bigger than yourself, unashamed and uninhibited.

This story was published in the print edition as “Where Gospel Caught The Holy Ghost.” Subscribe to the Oxford American with our year-end, limited-time deal here. Buy the issue this article appears in here: print and digital.