Untitled, 1969, oil on Eucatex, unique edition, by Antonio Henrique Amaral. Courtesy Casa Triângulo, São Paulo, Brazil, and Instituto Antonio Henrique Amaral. Photograph: Filipe Berndt

Mobile’s Forgotten Banana Docks

An Alabama hub once brought the Caribbean fruit to the nation

By Ravi Howard

Among the Mobile, Alabama, stories my father still tells, the one about the Banana Docks keeps returning to me. In that story, my grandfather, a day laborer, joined the other men who carried the six-foot-long banana bunches from the United Fruit boats to the refrigerated railcars. When a banana boat came in, the longshoremen gathered at Miller’s grocery on the corner of Texas Street and South Franklin, hoping to join a gang and get a day’s work.

“There were these great big chalkboards attached to the outside wall with the name of the ship, the cargo, and what time it came in,” he told me. “They’d have this big truck to carry everybody down to the state docks.”

Miller’s was a short walk from the family house on Hamilton Street in Down the Bay, an urban grid of shotgun houses and railroad flats. The neighborhood was framed by the sites of labor—the Mobile River on one side and train tracks all around. For the domestic workers like my grandmother, labor sent them north to the Oakleigh Garden District and Government Street. On the neighborhood’s south end, Brookley Army Air Field awaited, with day work for Black women with the families of officers.

I knew Mobile from secondhand stories more than memory. I was born in Montgomery and raised there and in Jackson, Mississippi. My parents left Mobile for college, and my childhood journeys to the city included weekend trips and reunions. The Down the Bay stories came like clockwork as we drove down Interstate 10, the highway built on top of the old neighborhood. The Texas Street exit runs over what used to be my father’s yard. He reminded me of this when he pointed out the last remaining pecan tree.

I remember the descriptions of the Banana Docks as if the memories were mine—as if I’d seen it all firsthand. As vivid as my imagination was then, the scene I pictured seemed distant and hazy. In time, I would see the pictures clearly.

While I was writing my first novel, set in Mobile, I searched through city archives and online for photographs to guide my descriptions. Once the book was finished, I kept up the habit, returning to the segregation-era Mobile photos of Gordon Parks, the photographer, writer, and filmmaker who was a childhood hero of mine. Icons and heroes can often help me discover a wider ensemble of their peers. Parks’s Life magazine photos led me to his New Deal work for the Farm Security Administration, and I then found the work of Arthur Rothstein, whose Banana Docks photos became the slideshow that matched family lore.

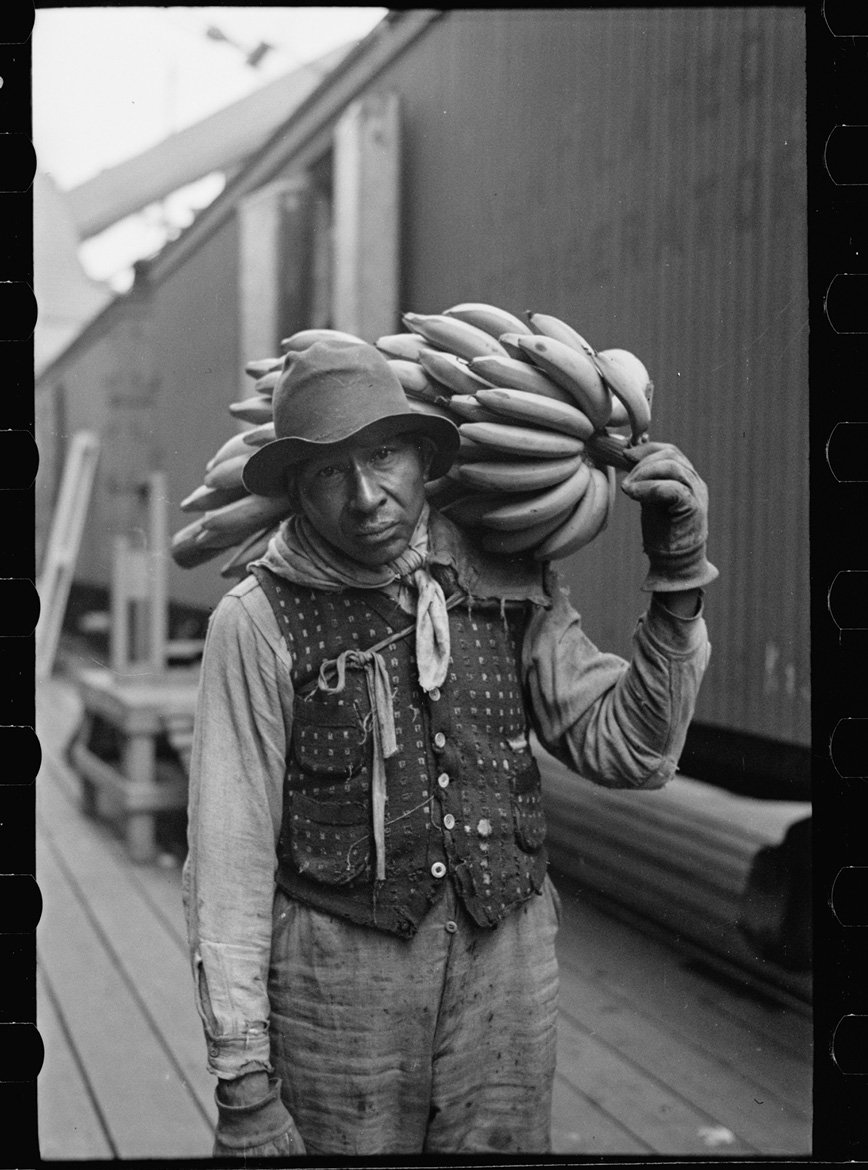

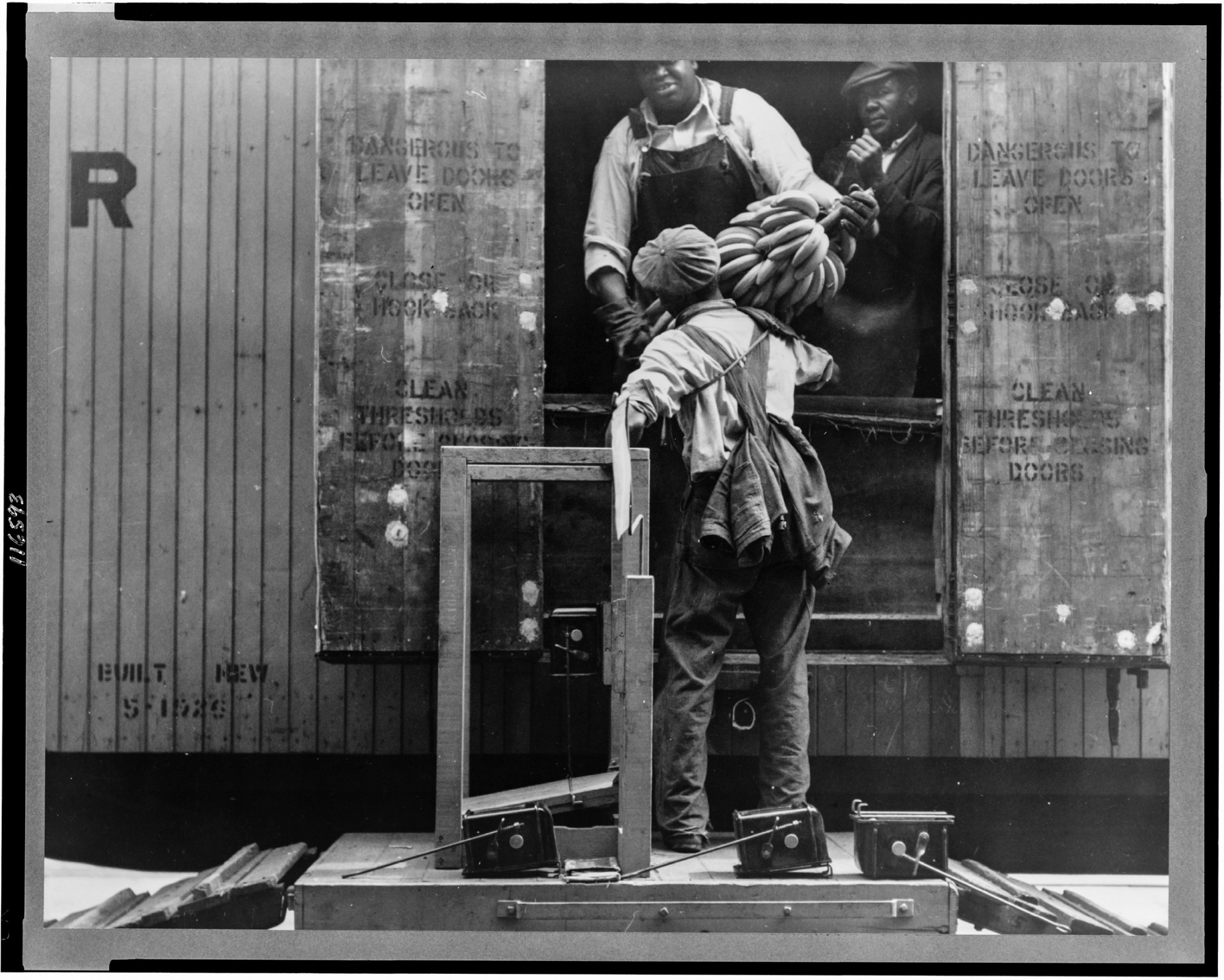

The picture I most often return to, dated 1937, shows three men at the moment of exchange, bananas from the hands of one worker to the shoulder of another. Two men stand in the shadow of the cargo door, and the third stands in the light as he takes the weight. The pad on his shoulder is secured with a piece of string that crosses his chest, knotted under his arm. He braces to balance the load, each banana hand weighing as much as eighty pounds. His stance looks practiced from the many trips and days of carrying.

The man’s jacket, laced between overall straps, shows how he prepared for the cool wind coming off the water, or maybe he’s ready for the chill of the refrigerated cars. The photograph speaks to the senses the viewer imagines. The weight of the cargo. The feeling of the air.

A worker at the banana docks in Mobile, Alabama, February 1937, a photograph by Arthur Rothstein. Courtesy the Library of Congress

A photography student at Columbia University, Rothstein joined New Deal–era photographers and writers like Parks and Dorothea Lange, as well as Works Progress Administration writers like Zora Neale Hurston and Eudora Welty. Rothstein’s journey through Alabama took him to Gee’s Bend, Birmingham coal mines, and the Tuskegee Institute, where he photographed George Washington Carver. Rothstein took over 80,000 photographs in his five years with the FSA, including the images of Down the Bay, the waterfront, and the day laborers along the Mobile River.

This picture has become a portal between the workers’ contemporary moment and mine. The depiction of work is not empty nostalgia or lip service about blue-collar identity, but instead shows the realities of what it meant to be Black and working in the Depression-era Jim Crow South. The subjects could be blood kin or spiritual kindred. I didn’t see my family among the men in Rothstein’s images, but I didn’t need to. The day laborers are unnamed, but their postures and gazes define them, telling so much about their lives and times.

My go-to scholar for questions about Mobile is Kern Jackson, director of African American Studies at the University of South Alabama and a friend of mine for years.

“We have a tendency to start wherever our feet are, learn about Black life and culture, and build out,” he told me.

I’ve listened to Kern’s oral histories in lecture halls and during our get-togethers with friends and family. He lives near the sites we both write about—the bygone docks and what remains of Down the Bay.

Start wherever our feet are. Build out.

When the open-air Banana Docks opened in 1857, Mobile was the fourth-largest city in the South, behind New Orleans, Charleston, and Richmond. It was the backdrop for compelling moments in emancipation. One of the last known slave ships, the Clotilda, carrying 110 enslaved Africans, docked in Mobile River in 1860. Across the bay, just five years later, Black Union soldiers helped to defeat one of the last Confederate strongholds at the Battle of Fort Blakeley.

This is backstory to what it means for Black dock workers to labor freely but unequally in the American South. The banana trade embodied the kind of exploitation that made it, like cotton and sugar, precarious for Black folks. Dead-end work was plentiful. An industry started during slavery continued during Jim Crow and the Depression. It offered only short-term survival and became a barometer of evolution and regression as the South moved into the industrial age.

The term “New South” first appeared in the Atlanta Constitution newspaper in 1874, urging a new era of Southern industry, including rails, ports, and factories. The future would surely hold a new wave of manufacturing and imports. At the 1876 Philadelphia World’s Fair, one of these imports was unveiled. In addition to new offerings like Hires Root Beer and Heinz Ketchup, the exposition introduced an odd-looking fruit called the banana. It slowly caught on, and by the beginning of the twentieth century, Mobile had become the third-largest banana port behind New York and New Orleans.

Photograph by Arthur Rothstein. Courtesy the Library of Congress

The bright side of this industry was that new Black residents found city work away from the fields. It was not ideal, but it was a start. Men made money on the docks and sent it back home to family members trapped in the debt of sharecropping. Those family members often followed, bringing more migrants into Mobile looking for work. The smaller regional migrations of port cities paralleled the Great Migration north. Life was better, but theirs was still a world of day work, landlords, and Jim Crow limitations.

In a Southern Foodways Alliance short film about her Savannah restaurant, The Grey, chef Mashama Bailey used the term “Port City Southern” to describe the African, European, and Caribbean influences that shaped the local food culture. The flavors, cultures, and techniques of the port city and region connect to ingredients and crafts from around the world. The Banana Docks echo that meaning, with small coastal cities along the Atlantic and the Gulf Coast becoming part of a gateway that reshaped the American palate. Coming through that gateway, bananas would become the most consumed fresh fruit in America in 2023.

The hero of the Gulf Coast banana trade was also the villain. Sam Zemurray immigrated from what was then the Russian Empire to Selma, Alabama, and got his start reselling overripe bananas that other merchants discarded. His first step toward prosperity would be the refrigerated train cars and cargo holds that let green and yellow bananas travel longer before ripening. His next step was dubious. When he moved to New Orleans, his fledgling fruit company, Cuyamel, found an ally in Manuel Bonilla, the former president of Honduras living in exile there.

According to his New York Times obituary, Zemurray “outfitted an exiled Honduran president and two soldiers of fortune with rifles, ammunition and a yacht.” Six weeks later, Manuel Bonilla had retaken his office, thanks to his ally, Zemurray, who owned 5,000 acres in Honduras. This would become standard practice, with companies owning their plantations and nearly owning the politicians. The term “banana republic” emerged from this moment, describing fruit executives’ control and influence over Central America and the Caribbean’s affairs. However unscrupulous, the strategy worked. By the time of his death in 1961, “Sam the Banana Man” had amassed a $30 million fortune.

In Zemurray’s lifetime, the banana went from oddity to staple. The World’s Fair exhibitors displayed their offering with a knife and fork, a signal that no recipe or standard yet existed for its consumption. Banana pudding was a sweet resolution to the question of what to do next. My father remembers his grandmother’s pudding, a good use for cheap, overripe fruit he brought home from his grocery job.

Though not beloved like Christmas fruitcakes with their pricier candied ingredients, bananas only required the packaged convenience of vanilla wafers and pudding—Nabisco or Jell-O or some off-brand versions. Whatever worked. Opening a box allowed for an affordable treat after a long day of work. The dessert only needed what time, money, and energy life in Down the Bay allowed.

Photograph by Arthur Rothstein. Courtesy the Library of Congress

In The Gift of Southern Cooking (2003), Edna Lewis and Scott Peacock included a banana pudding recipe with better ingredients. Still, they noted that the original dish was often made with whatever was on hand. The section heading was: It doesn’t have to be fancy. This language is much like grace notes on sheet music, instructing the soloist to play what they feel, what they are able to. For some, simplicity. For others, ornate lushness in celebration of what’s available now.

My father’s latest story mirrored the latter celebration. When I called to talk about these memories, he mentioned that at Thanksgiving, already stuffed, he was presented with a familiar dessert that was hard to resist.

“Somebody brought this great big banana pudding out there. I stopped eating everything else because I wanted some.”

The story of this dish mixes nostalgia and reality, which leaves room for lightness about a family history that was difficult but often hopeful. My grandfather’s trips to the chalkboard were the same. Sometimes there was work, and sometimes there wasn’t.

The final chapter in the banana years came through my uncle, Eddie Howard Jr., who tended bar at events held on the old Banana Docks years before they were demolished to make way for the convention center that opened in 1993. This was the newest version of the New South, where many of the old wharf spaces have been replaced by tourist attractions and cruise terminals. Before the final days of the Banana Docks, I imagine the shared space of a father and son, a generation later, working under the same roof that Arthur Rothstein captured.

Those photographs depict a moment while helping me to conjure so many others. It’s easy to see my grandfather and uncle just outside the frame. They are rendered not through a camera lens, but through legends and memories full of good times and hardship. Though the images include the ups and downs of Black Southern history, there is still a sweetness in revisiting the stories and pictures of a time and place that has come and gone.

This story was published in the print edition as “Down on the Banana Docks.” Buy the issue this article appears in here.