Every Hillbilly Can Govern

By Danielle Chapman

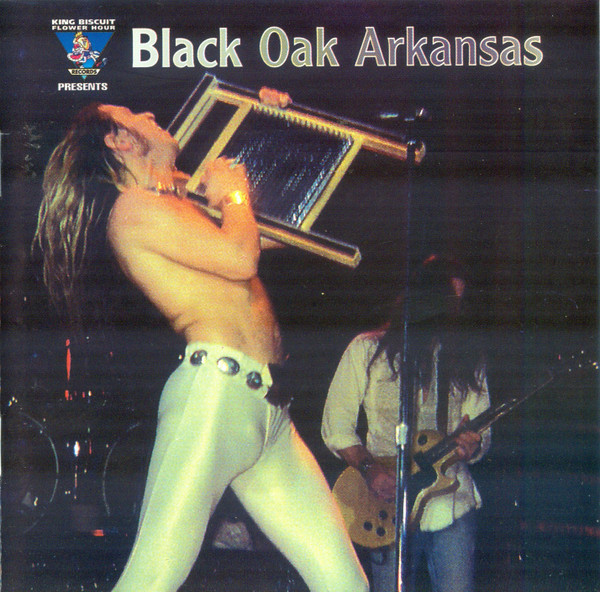

“Black Oak Arkansas – Live On The King Biscuit Flower Hour” CD Cover (1998)

In the Michigan neighborhood where I was raised—the ethnic composition of which my mother succinctly defined as “cracker”—Elvis Presley came as no surprise. Some of my earliest memories are of kids on the block who bore the cracker brand: the hooded eyes and goop-slick hair and shackled jeans; young men whose idea of making an extended remark consisted of slowing their native Kentucky—or Tennessee or Arkansas—drawl even further, turning the most laconic sentences into taffy. Or the blues.

Certainly not into culture. Those transplanted Southern kids, who had come north with their parents who worked in the auto plants, tool-and-die shops, and various post-war industries, knew as well as we Yankees that people like us did not know how to do that. None of us had ever heard that Lenin once proclaimed, “Every cook can govern.”

If we had, there probably would have been a lot more bands like Black Oak Arkansas, a lot sooner.

Who?

Why, the original generic Southern rock band of the early ’70s, the one that hailed from a small town (current pop.: 277) deep in the Ozarks. This band, self-taught if not self-disciplined, conquered that small section of the world, or at least of rock ’n’ roll, that exists between heavy metal and the Allman Brothers.

Black Oak Arkansas were the Rodney Dangerfields of rock, so lacking in anything approaching esteem (except, of course, self-esteem, which was a problem for another decade and another class) that the liner notes to their greatest hits album, The Best of Black Oak Arkansas, describe them as “gallopingonstage like escapees from a Dogpatch nut-house, cavorting with the physical abandon of the mountain men in Deliverance, buggering their audience with the raunchiest rock to be heard on this side of the moon.” In short, Black Oak Arkansas were not mere rednecks, or even crackers, but a breed even more feared by the middlebrow—actual hillbillies that rare kind of white people whom their own record company doesn’t have to treat as human. Not that Black Oak could exactly complain, their stage act being essentially a parody of the whole hillbilly yokel thing, in its post-’60s format (i.e. with pot instead of corn liquor fueling the indolence).

From 1971 to 1976, Black Oak found an audience while incessantly touring, pausing just long enough to release a prodigious stream of albums—ten in under six years. Onstage and on vinyl, Black Oak celebrated its hick background as the colossal anti-hip it was and made the guys in Bon Jovi look like pampered prep schoolers. Around this, lead singer and songwriter Jim Dandy Mangrum twisted a bizarre post-psychedelic pagan-Pentecostal religiosity directly connected to the band’s fixation on sex at its barnyard crudest, the pleasures of reefer and alcohol, and the glories of laid-back country living, barefoot and bad-ass. All this set against a background of abrasive sub-metallic noise from their three-guitar lineup, fronted by Mangrum (whose stylistic thrust could perhaps be seen as the inspiration for David Koresh), and sometimes supplemented by Ruby Starr, a no ’count wannabe blues babe from Milwaukee.

Black Oak didn’t make millions. At their biggest, the hit single “Jim Dandy to the Rescue,” a remake of Laverne Baker’s ’50s r&b hit, lifted them only to #25 on the singles chart. None of their albums made it to the million-selling platinum mark—only three snagged gold for selling half that much, and even High on the Hog, which contained “Jim Dandy,” peaked at #52.

Critics despised Black Oak. “They have never achieved competence—they are actively untalented,” wrote Robert Christgau, while the renowned Rolling Stone Record Guide declared the group (in a review not penned by the editor—me) “the pits of hard-rock senescence.”

The only critic who got it was proto-punk Lester Bangs, who commented, “There is a point where some things can become so obnoxious that they stop being mere dreck and become interesting, even enjoyable, and maybe because they are so obnoxious.” But of course Bangs would be the one to get it: he was a second- or third-generation California Okie and, therefore, pretty much a cracker himself.

Today, being obnoxious is the banal occupation of almost every new performer who comes down the video tube. The utter narcissism of Mick Jagger and David Lee Roth has begun to seem an almost poetic pose next to a generation of children who seem willing to swing from the chandeliers, overdose on command, or ’fess up to any false sin so long as we won’t take our eyes (who cares about the ears?) off them for more than a few seconds during their starburst, which blessedly never lasts more than an album or two. In a period such as this you’d think there would be a powerful Black Oak Arkansas revival. Or, at least, you would think so once someone reminded you of the formal precocity of their stab at stardom, or, presuming you weren’t there because still toddling or yet unborn, convinced you that the stories are really all true.

Because the stories pretty much are all true. (“There are many people whose police confessions begin with the words, ‘Black Oak Arkansas invited me to come out and party,’ ” the Minneapolis Star Tribune wrote just last February). It is the truth that Jim Dandy would harangue the audience with a spiel equal parts Elmer Gantry hellfire, Little Richard shriek, Dylanesque incoherence, and ahead-of-its-time psychedelic psycho-babble. It is an incontestable fact that in 1976 Black Oak Arkansas sued a local fundamentalist preacher for libel and beat him in open court, on the grounds that the bandmembers were not (a) going to “corrupt our young people,” (b) getting away with the equivalent of “set[ting] up a whorehouse down here in town”, or (c) “a mongrel group of satanic origins promoting drugs, sex, and revolution.” And they certainly did not deserve to have the preacher ask God to send a rainstorm to cancel the show they were playing—a benefit scheduled at the request of county officials to raise money for a new county health building—and then have him claim that they wouldn’t cancel the show if it did happen to rain, because “they love their sin too much.” (The band won $59.75 in court costs.) It is even true that Black Oak Arkansas was among the first popular rock bands who tried to interest their audience in political issues, campaigning to ban offshore drilling, legalize marijuana, and get kids registered to vote, while declaring, “Taxes is just a high level of protection money.” Any of which would be considered significant today, if not noble, were the same positions to be taken by an art-schooled pop singer from London or New York.

Alas, Black Oak Arkansas did not have any such credentials. Their attachments to the land and to the people who inhabit it (and listen to such scabrous music) did not have the gleam of irony or, for that matter, anything else that smacked of the “proper” distance between artist and society. Black Oak may have been uneducated and uncouth, but they were well aware of being more than “outsiders,” which is a good word to describe transvestites, anarchists, and artists, but will never do to describe what America (or, at least, the part of America with a public voice) thinks of the hillbilly, the cracker, the redneck. They may have lived hundreds of miles from a cultural center, but Jim Dandy and his clan were not outsiders at all. They were pariahs, as proved by their accents, their excessively (by the hipster standard) long hair, their bare chests and tight-crotch Levis, their roisterous tributes to sweaty orgies, and perhaps, above all, their clear connection to Pentecostalism, not as something learned from gospel records but as something experienced in the flesh, on home ground. Indeed, what drew the picture of their pariah-hood most clearly into focus was their allegiance to the Ozarks themselves, the band’s commitment to going up in the mountains between tours and living collectively like a bunch of Beverly Hillbillies with the sense to stay put and let the bankers come to them.

More civilized sorts may like to protest that Jim Dandy couldn’t sing—except that his gravelly tones sound more like Captain Beefheart than a truly unlistenable wimp whiner like Morrissey or that wheezing idiot from Blues Traveler. They can claim that the guitarists couldn’t play—despite the fact that the band was first signed as the Knowbody Else to the Stax label by the redoubtable Jim Stewart, and were found for Atco by Ahmet Ertegun, neither of whom was known for tolerating the inept. They could claim, with a great deal of justification, that the rhythm section was way too weeny for a band inhabiting the boundary between the Allmans and Black Sabbath, and they’d be right. But then they’d have to explain why civilized sorts tend to like the rhythm sections of, say, Björk, or just about any other alternative-rock group of the past fifteen years, all of which are weenier.

Or the civilized could claim that this whole genius-yokel act was a mere prelude to Lynyrd Skynyrd, whose Ronnie Van Zant was the quantum Jim Dandy, a redneck (if not a hillbilly) with poetic and forensic skills sufficient to fling the likes of Neil Young into the dust. And they’d be right, because Lynyrd Skynyrd was, let’s face it, the greatest hard rock group in American history. But if that happened, the civilized would have to deal with what Skynyrd was saying in its records, which were mostly about a bunch of guys with excessively long hair, bare chests, and tight-crotch Levis paying roisterous tributes to sweaty orgies in accents that bespoke a clear connection to not just Pentecostalism but also honky-tonks, including the fistfights that spilled out into the parking lots. Lynyrd Skynyrd is to Black Oak Arkansas what Franz Kafka is to the Marx Brothers, so there’s no getting out of swallowing this particular dose of reality medicine. The civilized media can ignore it, but both Black Oak Arkansas and Lynyrd Skynyrd will tour the United States this summer, and audiences will find them. They will find them because these bands are still of a perfect design that can awaken us to the fact that crackers are about as dumb as we treat ’em, and about two percent as inbred as the royal families over whom the civilized drool, and not any more likely to bugger anyone against their will than this week’s flouncing Limey starboys.

The fact of the matter is, we don’t listen to crackers (or the people who live next door to ’em, in case you’re wondering why I sound so aggrieved), and this is what rock ’n’ roll was invented to correct—invented, as it was, by white people from Mississippi and Louisiana and even Arkansas like Johnny Cash, Ronnie Hawkins, and Levon Helm, and by black people who were just that much more invisible...to the civilized.

I have no illusions, nor would I leave you with any. Sure, Black Oak Arkansas represent rock ’n’ roll at a very low level, but then again, that kind of makes them futuristic, since that level is pretty close to most of what passes for the top today, only with a sweeter temperament and more overt purpose. At the very least, Jim Dandy and his yeomen wanted to be heard telling tales by, about, and for the kind of people who need them. They also had the courage to hope that, in the process, they might change the world some. At the very least, they didn’t fall for the phony drug war, and they understood that while sex, drugs, and rock 'n’ roll make a lousy long-term political program, they are an aesthetic statement of vast power. In short, I think that preacher was right, and that’s what’s great about Black Oak and what was so great about rock 'n’ roll before it was taken over by tasteful makers of video advertisements and other marketing experts.

So y’all should listen to this stuff sometime. It will convince you that, if you got right down to it, every cook and every cracker could run the world, with a little assistance from the neighbors, and run it just as well as the “civilized” (you know, middle-class folks from Little Rock). Along the way, it will endeavor to murder your pretensions and allow you to dance on their graves. Give it a try. You have nothing to lose but your chains of respectability.