The Real First Lady

She Sang About Real People and Real Pain, Which She Had Damn Sure Experienced

By Julia Reed

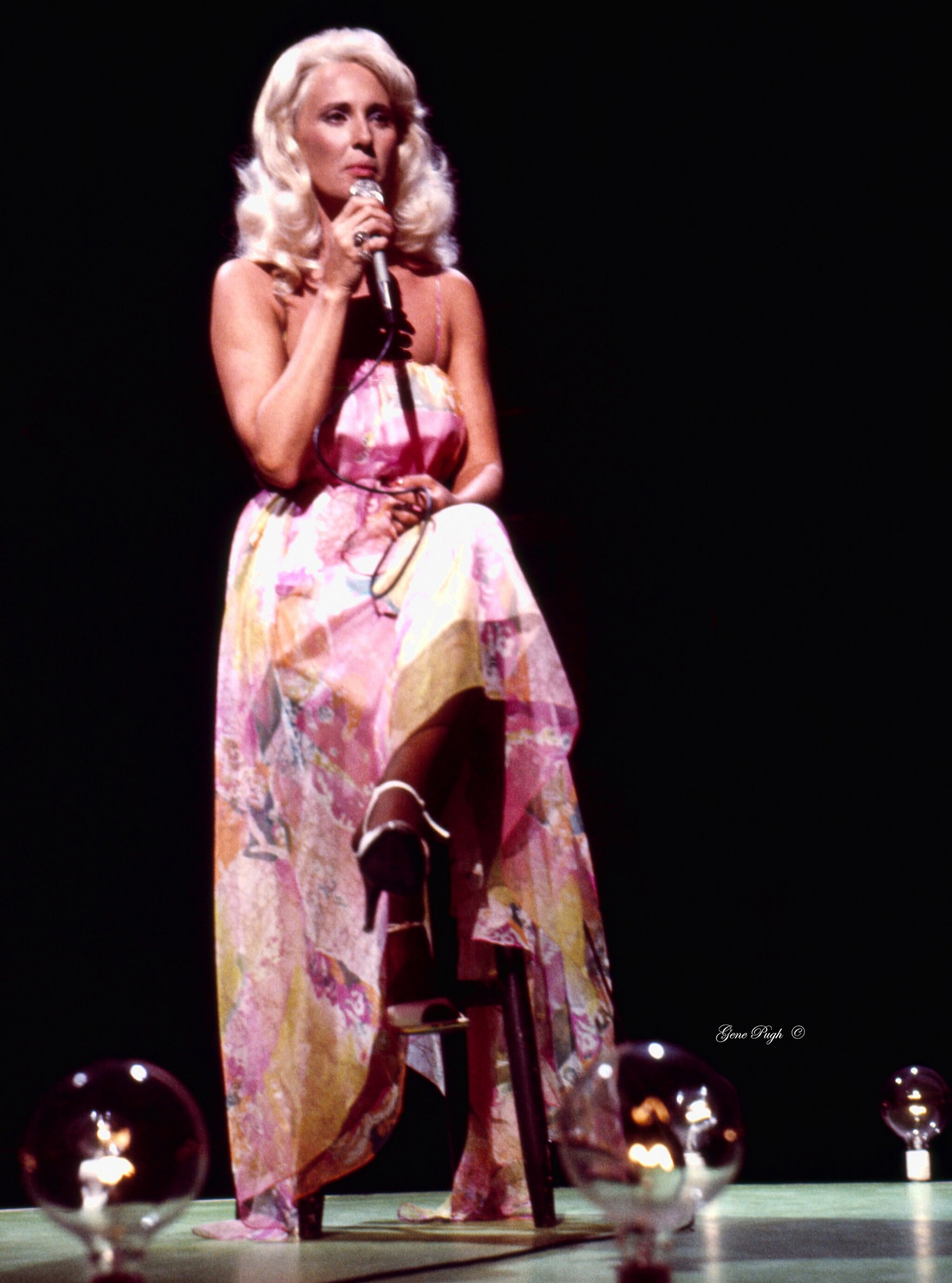

“Tammy Wynette at the taping of The Johnny Cash Show in Nashville, Tenn.” (1977) by Gene Pugh, via Creative Commons

It has reached the point that almost everything that happens in this country is somehow linked to Bill Clintons sex life. Tammy Wynette, the First Lady of Country Music, the possessor of one of the most unforgettable voices that ever existed, dies, and every obituary reminds us of the night Hillary Clinton appeared on 60 Minutes with her husband so he could acknowledge “causing pain” in his marriage. “I’m not sitting here,” Hillary said, “like some little woman standing by my man like Tammy Wynette.”

That irritated me then and it irritates me now because, aside from the incredible rudeness and classism of the remark, it is clear that Hillary never actually listened to the words of “Stand by Your Man.” Had she bothered, she would have known that the song is not about a woman hopelessly in thrall to her man but is an affirmation of the moral superiority of women—they are stronger and smarter and understand that “after all, he’s just a man,” which also happened to be a sort of inadvertent theme in Bill Clinton’s first presidential campaign. Every time something came up about Gennifer Flowers or dope smoking or the draft, George Stephanopoulos would patiently explain that his candidate was “a human being.” It would have been far more accurate if Hillary had said she was standing by her man like Tammy Wynette.

Also, if Hillary had read Tammy’s autobiography, she would have known that Tammy herself had not exactly been sitting around “like some little woman.” Unlike Hillary, Tammy always knew when to get up and go.

Tammy Wynette, born Virginia Wynette Pugh in Itawamba County, Mississippi, was married five times. She left her first husband, Euple Byrd, when she was twenty-two, after five years of living in a log cabin with no stove or refrigerator or running water. She already had three children (she was kicked out of high school for being pregnant with the first one), and when she put them in the car to head for Nashville and a career in country music, Euple laughed and told her, “Dream on, baby, dream on,” which irritated Tammy. "Don't tell me that I can’t do something,” she said, “ ’cause I’ll show you I can.”

She left her second husband, failed songwriter Don Chapel, after her singing partner, George Jones, interrupted an argument between them, kicked over the dining room table, and declared his love for her. She got in the car again, this time with Jones and the kids, and they drove all night to Georgia. When their marriage fell apart after an heroic six years, Tammy generously took half the blame, attributing their breakup to “his nippin’ and my naggin’,” but there had been plenty to nag about. In addition to serial bouts with booze, cocaine, and women, Jones had a penchant for guns. When a friend, the songwriter Earl “Peanut” Montgomery, found the Lord and quit drinking and urged Jones to do the same, Jones pulled out a .38 and said, “See if your God can save you now.” One night he shot up his and Tammy’s Lakeland, Florida, mansion with a rifle before aiming it at her. He was finally hauled off in a straitjacket.

A year after her divorce from Jones, she married Nashville realtor Michael Tomlin and divorced him forty-four days later. She had an affair with Burt Reynolds, whom she saved from drowning in her bathtub, and finally married producer and songwriter George Richey. When she died, she’d been married to Richey for twenty years, and I don’t blame her. He co-wrote one of her best songs, “ ’Til I Can Make It on My Own,” and the first time I ever met him he was making homemade biscuits with sausage gravy for breakfast.

After the 60 Minutes slur, Tammy declared that Hillary Clinton had “offended every country music fan” as well as all the folks like herself who have “made it on their own, with no one to take them to the White House.” Tammy grew up on her grandparents’ farm picking cotton and later went to school to become a beautician. Once in Nashville, she co-wrote most of her songs and became the first woman to sell a million records.

She demanded and received an apology from Hillary, and agreed to perform at a Clinton fundraiser, but she never got over her private anger. At her death, the Clintons and the Gores sent flowers, and the president said, “Her trademark style has filled our hearts and made her a legend,” which was one of those tributes that doesn’t actually mean a thing.

One of her trademarks was an enormous grace and generosity that not only benefited the president but also made her funeral seem like a Nashville version of Princess Diana’s. Fifteen hundred people crammed inside the Ryman Auditorium for the public memorial service, which was televised worldwide on CNN. She had sung about real people and real pain, which she had damn sure experienced. She said her stint on the short-lived soap opera Capitol was a natural: “My whole life’s been a soap opera.” In addition to the multiple marriages, she had more than thirty major surgeries. She survived an infection that put her in a coma, and she did a stint at the Betty Ford Clinic for an addiction to painkillers, which was interrupted by emergency surgery at the Mayo Clinic. She was once abducted from a Nashville shopping mall and beaten, her daughter Georgette was the target of death threats, her tour bus, the Tammy I, burned up, and she was forced into bankruptcy when a crooked savings and loan cheated her. It’s no wonder that one of her favorite gospel songs was “Death Ain’t No Big Deal,” which Jake Hess sang at her private church funeral.

She could also carry feeling other people’s pain to heights not even Bill Clinton could match. A few years ago after an outdoor concert in Nashville, she was changing clothes on her bus when her former bus driver appeared at the door asking to see her. Tammy had first met the man at the local homeless mission, where she was serving Thanksgiving dinner and where she later offered him a job driving the Tammy II. One day he had a Vietnam flashback and literally jumped off the bus in the middle of the road. He surfaced a few months later to sell the details of Tammy’s personal life to the National Enquirer. Tammy had not heard from him since, and she was on her way to visit her husband in the hospital where he’d just had quadruple bypass heart surgery, but she spoke to the former driver for more than an hour. “He needed me to talk to him,” she explained. “He needed me to forgive him.”

An over-the-top press release once said, “She’s the fabric of legends, but cut from soft cloth.” She was certainly fragile. Her former masseuse, the video producer Joanne Gardner, told me Tammy was covered with so many scars “it looked like Zorro had gotten after her.” She was so tiny—five foot four, size two—that I once saw her put on one of the beaded dresses she wore onstage and fall down beneath the weight of it.

But she was also a trouper. The night her mother died in 1991, Tammy was hosting a fan club cookout at her house, First Lady Acres. “Meemaw” was unconscious and hooked to a respirator in a spare room off the kitchen as the fans arrived outside. Entertainment Tonight’s Leeza Gibbons prepared to interview Tammy, who was in turn “introducing” Leeza to her mother. Meemaw took her last breath, and Tammy fell apart, her mascara melting down her face. Gibbons offered to go and greet the fans in Tammy’s place, but Tammy would have none of it. She pulled herself together, went out and mingled, and at midnight got on the bus to drive to Canada for a single show, returning in time for Meemaw’s funeral. “You tell Tammy two hundred people want to see her in Branson, Missouri, and boom, she’s on the bus,” said her friend and publicist Susan Nadler at the time. She was of the generation of country entertainers who never stopped touring until the end, always thinking that but for the grace of God she might still be picking cotton.

She kept a crystal bowl full of the cotton she had picked in Itawamba County in her living room as a reminder. She also kept her beautician’s license, just in case. In her book, she ran a photograph of her enormous gold-fixtured bathroom at First Lady Acres next to her first bathroom, an outhouse. Tammy’s life was a lesson in grace and humility that the First Lady would do well to learn. Considering Hillary’s current circumstances, she might do even better to learn the lyrics to some of Tammy’s other songs—like “Your Good Girl’s Gonna Go Bad.”