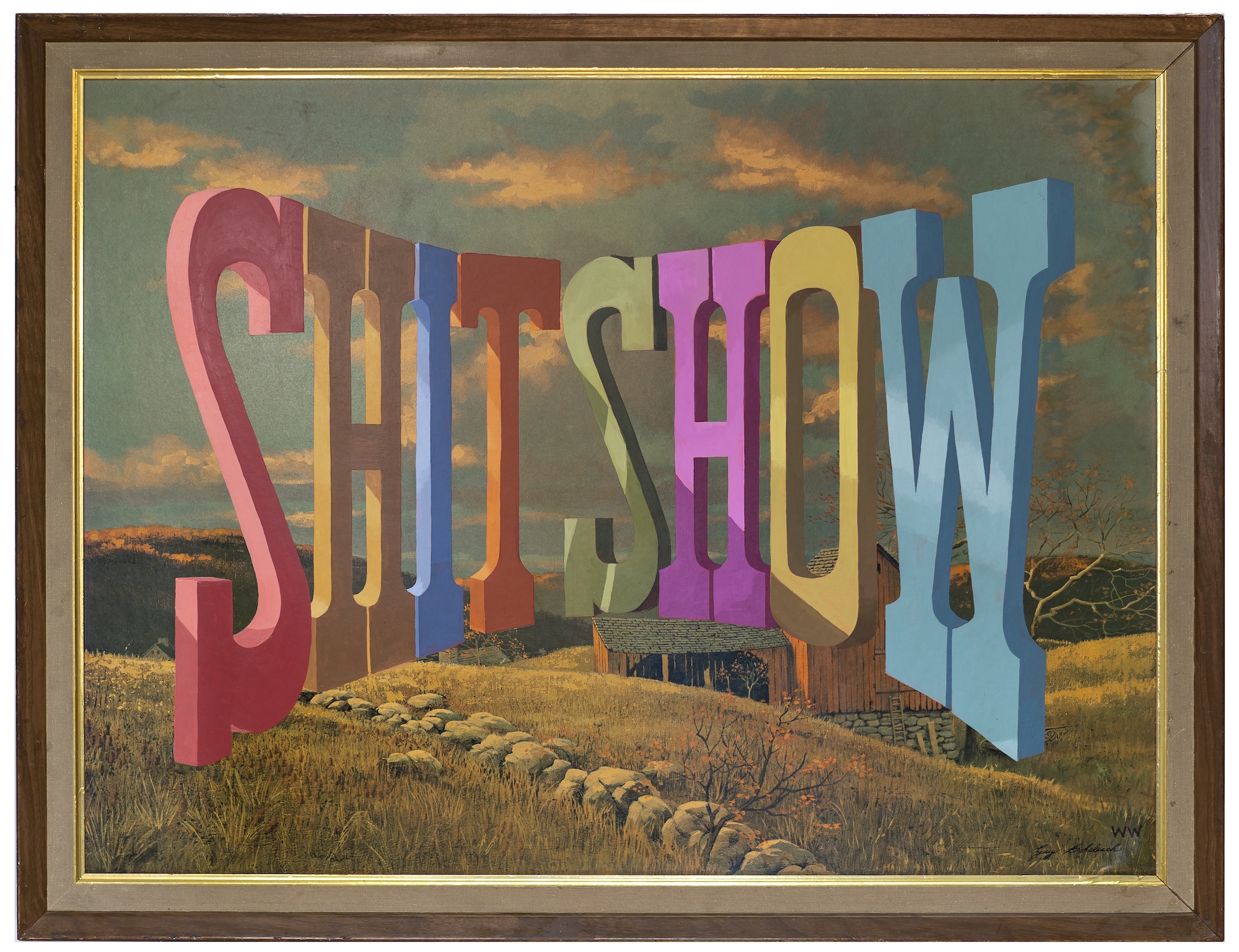

SHITSHOW, 2022, acrylic on framed vintage offset lithograph by Wayne White. Courtesy the artist and Joshua Liner Gallery

Secondhand Sublime

Junking with the weirdest landscape painter in America

By Paul Reyes

“From passive places his imagination sprang a harpoon.”

—Charles Olson, Call Me Ishmael

On a clear day, you can see seven states from Lookout Mountain, from the edge of a maze of boulders known as Rock City, perched seventeen hundred feet above Chattanooga, Tennessee. That’s the claim, anyway, that you can see this geographic shoulder of the South, and any driver within a five-hundred-mile radius of Chattanooga is practically bullied into visiting (to admire the view and other “wonders” Rock City possesses), thanks to a sign painter named Clark Byers, who for thirty years painted SEE ROCK CITY on the roofs and sides of nearly every barn he could find. The message is ubiquitous if not maddening, about as Americana as Rock City itself. And for every barn that has collapsed, or whose roof has faded, at least one billboard has risen along the interstate, so that heading south, say, from Nashville to Chattanooga on 1-24, these bright, geometric slogans leap up from behind the tree line with a jack-in-the-box rudeness—SEE ROCK CITY, SEE RUBY FALLS, SEE SEVEN STATES—one about every quarter mile. Like panels in a pop-up book, as incessant as Christmas carols. So many of them, I lost count after a couple dozen.

The South, its vistas, phrases, the hand of man, etc.—it was all coming together concretely now, these themes flitting around in my head like trapped birds after I’d had long conversations on the phone with Wayne White, a painter whose surrealist landscapes have hijacked my attention lately. Wayne had flown from where he lives in Los Angeles to his hometown of Hixson, just twenty minutes north of Chattanooga, and had invited me to visit, to meet his parents, meet his wife and kids, see the Civil War stuff, get a feel for the place. A private tour through the small chambers of an artist’s youth, where the land, code, mistakes, and triumphs all cooperated to mold an artist whose work has revealed to me the thrill of art.

I knew this thrill existed for others, having had some inclination of it as a student, though back then my experience was mostly limited to appreciation, nothing so visceral. I admired Vermeer's clean, melancholy light; and Lucian Freud’s portraits, painted in thick, geologic chunks, were a marvel to see up close; and maybe Giacometti’s Man Pointing was the first time high art communicated something, some tremor, though after many visits and much staring I gave up trying to articulate this statue’s effect (which was just as well, since any explication likely would have ruined the pleasure of that illogical zap).

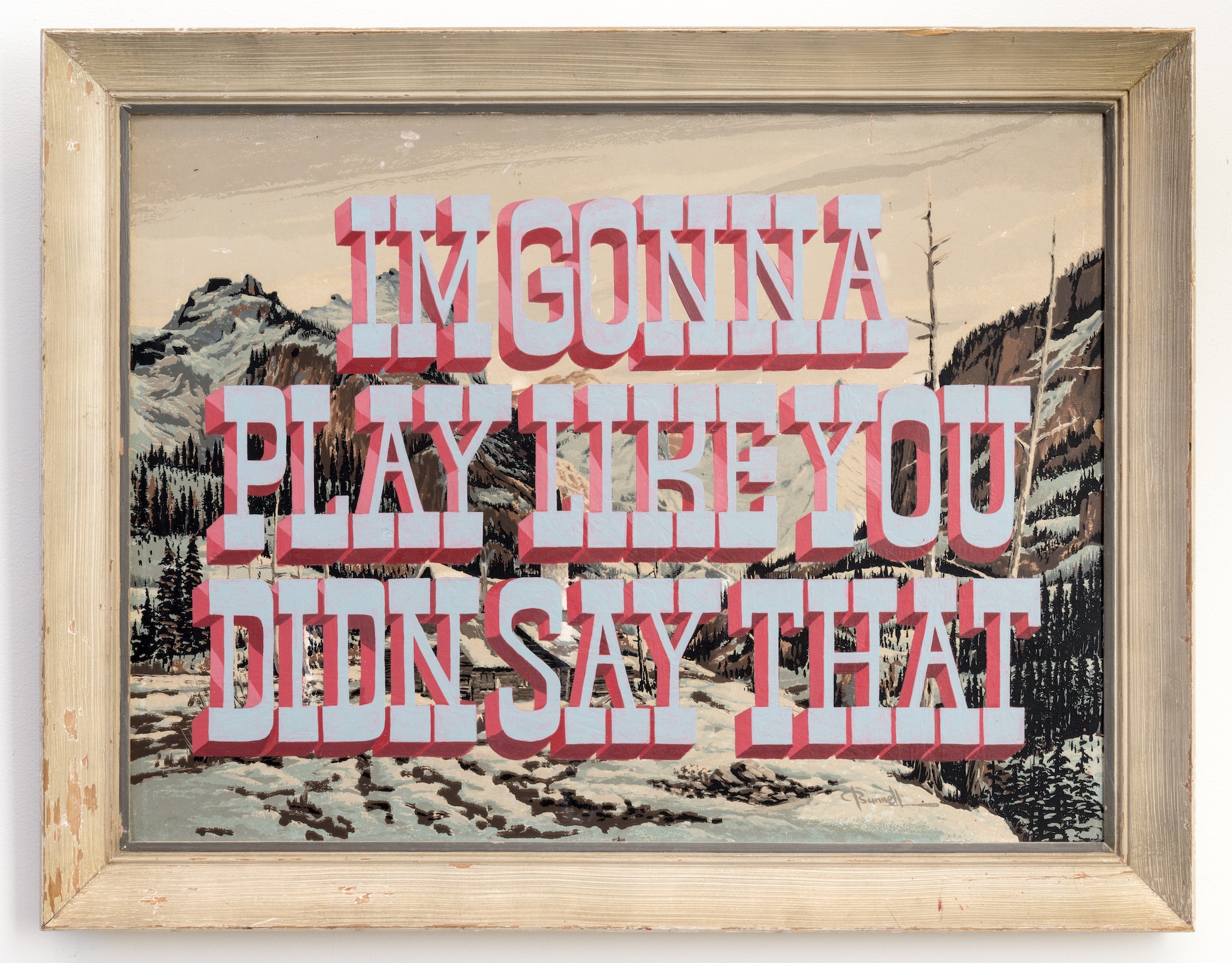

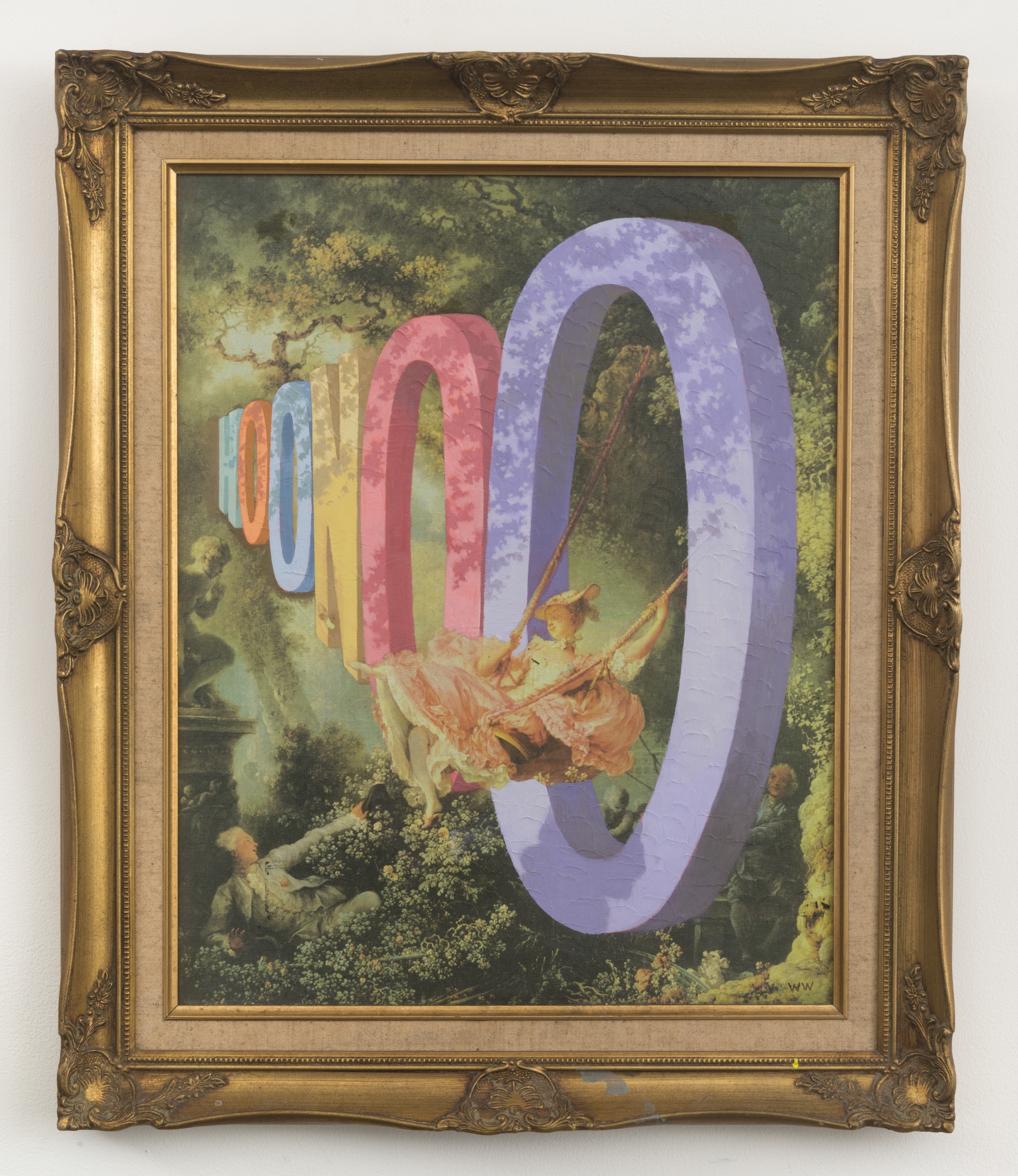

But Wayne’s paintings—for me, at least—they trigger a kind of logorrhea, an enthusiasm and gushing that seem appropriate (if not predictable) since language constitutes half the painting, pushing the surrealism, while the romantic landscapes that frame the language are the grand tradition reconsidered. Wayne doesn’t actually paint the landscapes, though; rather, he paints onto them—or into them— manic phrases, foreshortened or disassembled, on a scale to match the trees. They resemble Stonehenge letters arranged by the hand of a meticulous, nervous creator: acronyms standing in tall grass; a word balanced delicately above a glass-flat pond; a sentence stretching deep into a forest or curving around a cliff. Through this strange energy and juxtaposition, these paintings become an all-American conflation of traits: idyllic, ironic, childish, neurotic, confessional, land-obsessed—a country told in a painting each time.

Granted, I possess a layman’s eye. But genuine excitement from art—not the academic fuss generated by art’s inner sanctum, but an undirected experience, the jolt that registers somewhere between the emotional and cerebral, that outburns admiration and dips a toe into the holy shit!—this sensation is hard to come by for most of art’s uninitiated. It’s a rare moment in any expressive tradition, and far more familiar to music than painting. But Wayne’s paintings, through a curious approachability, get you there, prick the senses. The result varies, and is sometimes audacious, sometimes immature, but usually clever and always sincere, albeit a sideways sincerity. An honest irony.

Ergo Chattanooga. Because in every phrase floating in a vista is a tonnage of personality, perhaps genius. And given the chance, who wouldn’t want to learn what makes a genius tick?

Turns out that Chattanooga was full. A Harley-Davidson convention had taken over the city, and it was swarming with heavy, middle-aged suburbanites donning leather but looking altogether too clean to be riding Harleys. Yet here they were, making a racket as far north as Hixson, cranking-up as early as 9 A.M. at my hotel, where Wayne finally picked me up so he could show me around. He was almost indescribably normal looking—not too tall, vaguely late-forties, a hangdog charm—his stand-out feature being his unfashionable, thick plastic glasses. The drive was a little tense; Wayne was rough behind the wheel. And anyway his wife, Mimi, and kids, Woodrow and Lulu, were at his parents’ house and expecting him back by lunch for a family thing. So he was pointing out the old landmarks in a rush, cramming them between stops at thrift stores—where he finds all his landscapes, what he calls the “over-the-sofa” variety of chintzy waterfalls and snowcapped mountains—and fleshing out what he promised was a pretty good backstory.

We were on the subject of his father.

“The sidelong glance,” Wayne said, executing the look, “I learned it from my daddy, from Southern men. That deadpan humor, holding your cards close to the chest, that kind of thing." We were waiting at the exit of a parking lot, looking for a gap in the traffic. Wayne had gestured to the Baptist Church across the street, where a bowling alley used to be, where his father, Willis White, would bring him on Tuesday nights, league night, providing enough boredom that Wayne took to sketching caricatures of the team for about fifty cents a sketch. He cleared about five bucks a week this way, enough cash to buy junk food and comic books to tide him over until the following week when the league got together.

The Bethel Thrift Shoppe was somewhere nearby, but Wayne was having trouble finding it. Something was off. The barbershop he remembered was now an AutoZone. That parking lot over there was new. The map in his head wasn’t clicking with the actual street. How often did he visit Hixson? “About once a year.” And still, he hardly seemed to recognize it, or refused to recognize it.

Both of Wayne’s parents come from the town of Henagar, Alabama (pop. 2,400). Willis White was a high-school quarterback, the son of a farmer, while Billie Wilkes, fittingly, was the high school’s head cheerleader, and the daughter of the richest man in town, Roy Wilkes, whose Log Cabin Cornmeal helped create a respectable family fortune. “Then along comes my old man from the wrong side of the tracks,” Wayne said, “and he gets Billie Wilkes and moves on up in the world. My grandparents weren’t too happy about it.” Willis and Billie eloped and moved to North Georgia, then to Hixson, where Willis found a job at the DuPont nylon factory nearby and stayed on for the next thirty-eight years. After a daughter, Wayne was born in 1957.

He’d become an angry teen, of the small-town-angst variety, running with a group of country hippies who called themselves “freaks.” They were all from working-class families, and their rituals against boredom included dropping acid and backpacking through nearby Soddy Mountain, speeding along two-lane roads in muscle cars, scaring girls. Something about it felt disingenuous to Wayne, but he stuck with them. Whether it was out of fear of turning his back on such a tough clique or a genuine fraternal connection, he’s still not sure. “I was scared a lot of the time when I was with them, but I got kind of a weird thrill from it, too.” The freak spell included a few low points, including an arrest for stealing a mailbox (church property, one-year probation).

“I don’t know why,” Wayne said, “but I became self-destructive. I went through that mad-at-the-world phase, like everybody does, and then I went through a phase where I realized I had a right to be mad.”

Which lasted how long?

“Until I was about forty.”

The anger hadn’t completely evaporated; or, being back in Hixson, the old juvenile angst was being stirred up. At a gas station on the corner, schoolgirls hawked a car wash, and not ten yards away was a motley spread of junk for sale on the grass. He slowed down and scanned the pile. “My mother’s a junk dealer,” he said. “She junks all the time. She had a flea-market stall for years, and our home is crammed full of crap: some of it good, some of it really nice antiques, some of it the kitschiest stuff you can imagine. She’s obsessive with stuff. It’s not filthy or anything, but it’s crazy. It’s just this hodgepodge of Americana. And she kicked it into high gear after we moved away. Drives my old man nuts. I think she’s a frustrated artist.”

The thrift store, finally, we could see it in the strip mall just ahead.

IM GONNA PLAY LIKE YOU DIDN SAY THAT, 2016, acrylic on vintage offset lithograph by Wayne White. Courtesy the artist and Joshua Liner Gallery

Thrift stores are goofy haunts, about as distinct as bars or shopping malls, but lonelier, and with that peculiar odor of the thoroughly neglected. The main pleasure here, of course, lies in findng the unappreciated prize.

I had never thought, in any of these places, to go straight for the knickknacks, the domestic junk. I usually snoop among the jackets or shirts, and maybe pick through a stack of books. Wayne, however, with the smooth premonition of a television detective, walked right up to a painting, no confusion, tucked between a popcorn maker and a bicycle helmet. It was a simple piece, about the size of a textbook: a water pump, a bucket of daisies, a weathered house in the back ground, maybe somewhere in the Plains. On the shelves were por traits of cherubs, still lifes of fruit, bland seascapes, etc. I thought this was a joke; it was too easy. He’d simply walked right up and grabbed it, no second-guessing. He brushed off the dust, tilted it— dull, anonymous, but that’s what works for him. “If it’s too famous,” he whispered, “it looks like you’re rippin’ on it.” He held it up. “This one’s kind of funky,” he said, rubbing a bald spot on the canvas, “but I think I can work with it.”

The thing looked blanched. I suggested he might brighten it up a little.

“No,” he said. “Not at all. I work with the patina that’s already on there, and the tone that it has. I sort of cue the color of the text to the tone. That’s part of the whole illusion, the right tonal balance. And the tone is always based on the dinge—there’s different degrees of dinge, of course. It also has to be a reproduction on cardboard. If it’s on paper, it won’t take the paint.”

This place had once been a small local department store, and he showed me where all the toys had been, where he spent hours as a kid. The aisle was mostly packed with blenders now. I was getting excited about the metaphorical angles here, but Wayne was ready to go. “These places are all pretty much the same,” he said. “Some people interpret them as the true receivers of culture. Like my wife, she loves these places, and can read all kinds of things into them. I just target what I want and get out.”

Back on Hixson Pike, Wayne took a shortcut to the next stop, the Dogwood Shop, by cutting through a neighborhood where the elementary school faced a cemetery directly across the street. You could exit the school doors and walk right up to a headstone fifty yards away. “I took my kids over to my elementary school yesterday,” he said. “We snuck into my first-grade classroom. I hadn’t been there in forty years. I think this might be part of my big myth: I liked drawing stuff, but I never knew what an artist was. My parents never really communicated to me that you could be an artist. Not until first grade, the first day of school. The teacher had us draw these crayon drawings of our lunch. And then on the second day of school, she goes...” (here he did a creepily affected impersonation of her, so that she sounded kind of like a barfly, but smitten with him) "You know, class, I’ve been looking at your drawings, and I want to get a young man up here. Wayne White? Wayne White? I want the young man to come up here. And she stood me in front of her and she said: This young man is going to be an artist one day. Man, that just seared into my memory. I remember the look on everybody’s face. So I stood on the holy spot yesterday with my kids, and I’m about to get all weepy. And my kids are like, ‘Yeah, okay, Dad. Let’s go.’ I’m, like, ‘Shut up! I’m trying to have a moment!' "

We found the Dogwood Shop, parked, and could see the prize right there in the storefront window: a snow-capped mountain with three waterfalls and a sparkling brook. A perfect canvas. Wayne stepped inside, grabbed it, paid for it, and was back at the car in about seven minutes, half the painting done.

Since that big moment in first grade, Wayne focused on cartooning, even through his freak phase, with work showing up in the pages of the school paper. Eventually he enrolled at Middle Tennessee State University, where he studied painting. By the time he graduated, though, he’d become disillusioned with it. “I thought painting was irrelevant. I saw the inherent class struggle in it, and, being a working-class kid, I was turned off by the whole upper-class game you had to play within it, getting into galleries. The stuff only winds up on rich people’s walls. Plus, I wanted to communicate more directly, and I knew I wasn’t going to make movies, and so the logical thing was comics.”

With this desire for a more potent form of expression, he happened across Art Spiegelman’s Raw magazine one afternoon at a comics book store in Nashville. The confessional power of the adult underground comic resonated with him. “It all just came together in a nice kind of synthesis,” he said. “I immediately saw something that was a fresh alternative to the art world. Raw had everything in it: the edge, the storytelling, the sophistication of painting. It was an art-world worthy object, yet it was comics. That cinched it for me. I thought, This is the wave of the future.”

Wayne read that Spiegelman was teaching at New York’s School of Visual Arts and decided to track him down. He loaded up his 1970 Maverick and drove to Manhattan, parked across the street from the school, and roamed the building until he found Spiegelman. “Just went in there and started stalking.” He was lucky: Spiegelman only taught twice a week, and Wayne just happened to go looking for him on one of his teaching days, between class hours. He spotted Spiegelman in a hallway and introduced himself. “He didn’t know what to think,” Wayne said. “I mean, I was a complete alien bird to him. A redneck boy from Tennessee. But he was very gracious.” Spiegelman was fascinated by the specimen from Tennessee, and over coffee critiqued the illustrations he’d brought with him, and afterward invited him to join the class. He even offered him a chance to volunteer as a studio assistant—fetching coffee, doing small errands, running photostats, posing for a few action scenes in Maus (hold a stick, pretend you’re shooting a rifle, etc.), which Spiegelman was just beginning to sketch out at the time. Wayne found an apartment in the West Village, got a job at the Empire Diner as a short-order cook on the graveyard shift, and committed himself to comics. He fondly remembers the salon atmosphere of the studio, the particular breed of intelligence these writers and illustrators shared—a group that included Mark Newgarden, Kaz, Gary Panter, Ron Hauge, and Wayne’s future wife, Mimi Pond, who was a part of Matt Groening’s circle at the time. “I hung out with writers and cartoonists much more than painters,” Wayne said. “I cut my teeth around those guys. And they were no-nonsense guys, too. They wouldn’t let you get away with anything.” To a large degree, the intellectual pressure this crowd generated chiseled Wayne’s own approach to craftsmanship, because with comics, he says, “there’s no ambiguity with the craft. It’s either working on the page or it isn’t. You can’t fudge anything like you can in painting. In painting, you can fudge all over the place. People will read into it, and you can rest on that. But with comics, everything has to be tight and resolved with a certain elegance and a certain refinement that cannot be faked. Painters can fake a lot. They really can.”

Spiegelman’s class ended, and Wayne slipped into a deep funk. The job at the diner had overwhelmed him so much that he’d failed to complete his final project for the class. Embarrassed, he avoided the studio for a while. He needed fresh inspiration, and so he eventually tracked down another of his heroes living in New York—a fellow Tennessean, sculptor Red Grooms. Meeting Grooms turned out to be even simpler than meeting Spiegelman. Wayne walked into the Marlborough Gallery, which represents Grooms, and left a note for him; within a couple of days, Wayne was invited to lunch, and by the end of it was offered a job painting one of Grooms’s sculptures. Like Spiegelman, Grooms took to Wayne quickly. He seemed fascinated by his cartooning background, and peppered him with questions about it. He even drew a portrait of Wayne called The Cartoonist. The mentorship had a profound effect. “I learned a lot just from hanging around Red,” Wayne says. “I learned how to act. Just the way he would talk to people about art, the way he could do it without being pretentious. His whole style, I really admired it. He was the the kind of role model I needed back then, because I was confused about how to be both real and sophisticated about art at the same time. And Red could find merit in everything. He wasn’t uptight or sniffy; he was receptive to the world. That was eye-opening. Most of the art teachers or artists I’d known up to then were very exclusive in taste, trying to climb up into the tower somehow. And here’s this guy who’s well-respected yet completely ready to experience everything, and very unprejudiced.”

While working for Grooms, Wayne’s cartooning gigs followed at a steady pace: Work for the East Village Eye lead to a spot with High Times magazine, which led to spots with The Village Voice and Rolling Stone. “That kept on till ’85, when the puppet thing started slowly creepin’ back.”

Apparently, a puppet thing had begun in college, a punk-rock skit he continued to put on at East Village nightclubs and keg parties. The skit, with a cast of puppets Wayne crafted himself, opened innocently enough, but would end up with puppet veins bursting open to a punk rock score. “We had these tubes that pumped out big, chugging drafts of blood all over the audience. We’d trash the stage at the end, run out into the audience, just be obnoxious. Real weird, confrontational theater.” The puppetry picked up speed when an old friend called from Nashville and helped Wayne land a spot as a puppeteer and set designer for a public-television children's show called Mrs. Cabobble's Caboose. (That the Nashville school board saw in Wayne's punk puppet ethos a model for its children’s programming attests to some very forward-thinking liberalism among the board.) And this gig, in turn, was enough to impress producers at CBS after Wayne returned to New York a year later. Hiring was underway for a new show starring actor Paul Reubens, whose character Pee-wee Herman would be the star of Pee-wee’s Playhouse, the freaky, brilliant children’s variety show that made Reubens a pop-culture icon. Wayne helped design the set, a Groomsian, expressionistic assemblage that came alive in fits, in which actors, robots, a genie, and puppets all mingled with cartoons and stop-animation creatures in a kind of lithium-induced obliviousness. Wayne also handled a few puppets, including Mr. Kite, Randy, and Roger the Monster. Three Emmy awards came out of this work. “That was just like a completely new second act,” he says. “A new world in which I was known as a set designer.” Wayne had married Mimi by then, and the two of them moved to Los Angeles where she continued to work on comics while the set-design jobs came at a good pace, some gigs better than others: Shining Time Station with Ringo Starr, Peter Gabriel’s “Big Time” video, and the Smashing Pumpkins’ video for “Tonight, Tonight,” with smaller jobs in between.

The painting habit resurfaced in 1989. Wayne rented a downtown studio and began exploring an obsession with American history through Civil War battle scenes—crowded, fussy, glum—and more Romantic landscapes. “I was trying to go for a heroic effect,” he says, “with attention to the majestic clouds and the trees and the mountains just so. But really, a lot of them were just exercises in learning how to paint realistically, because I never really even trained that way at all. I never had any academic training. My art-school experience was all Abstract Expressionism and just making sloppy messes.”

The work evolved into more surrealistic scenes, from grim battle field aftermath to soldier-ghosts to soldier-hillbillies to allegorical scenarios involving werewolves, his primal fear. “Mimi and I argue about this all the time. She thinks the Mummy is the scariest thing out there. But fuck that, the Wolfman’s the scariest. He’s my idea of terror. If I want to scare myself, I can always think of the Wolfman’s face. It all comes together with him.”

This awkward self-confrontation began to wear on him, and as with his pilgrimage to New York, and meeting Grooms, and going against whatever grain dulled him, Wayne made a radical adjustment based on instinct. While painting yet another Civil War scene, he noticed a thrift-store lithograph he’d bought some time back for its frame. On a lark, he grabbed it and put it on the easel and began articulating the insecurity that had been grinding him down. The surrealistic elements of his work so far, he admitted, rang hollow. “I said to myself, You’re trying to be an intellectual. You’re not an intellectual. Just face it. I got angry with myself, and I suppose the whole thing was born out of disgust with absolutism and intellectualism. I realized there’s a limit to knowledge. There’s a point where it drops off and nobody can say a word. A no-man’s land when it comes to being human, an absurdist point where if just you relax and give in to it, there’s a truth and a beauty there.”

He was already stuck on how to incorporate text into the painting he’d been working on (“putting it on top of a building or something, I wasn’t quite sure”), and when he switched paintings, the dime-store lithograph seemed to open up to him. “I’d always painted landscapes that became a stage for this little action that I’d put right in the center. And that’s when I noticed that these cheap-o landscape reproductions had the same kind of structure. They had a center stage where you could put the action. But I also knew I wanted to create something that was completely out of time and place. I wanted to get it to that weird dream state that I’d felt very close to, but I didn’t need all this theory behind it. Just something that exploded right off, right at you, and you got it. I knew the painting should be able to work cold.”

Letting go, he began painting a phrase directly into the woods of the lithograph in front of him. The result was his first textual landscape, Human Fuckin’ Knowledge, a comparatively straightforward piece in which the phrase disappears in a straight, foreshortened line through a clearing of Northern pines, the white plastic letters reflected in a small pool at the foreground. He knew he’d hooked into something, that finally the threads of his obsessions were coming together. But it wasn’t until friends and colleagues saw the work that he realized he was communicating with the right intensity. “People saw them and went nuts. A lot of times you don’t know what you’ve got until somebody else sees it. And that’s something artists have to rely on sometimes, and have a hard time admitting. Sometimes your breakthroughs aren’t apparent to you. But I’d never had a reaction like that to anything I’d painted before, so I was off to the races with this one.”

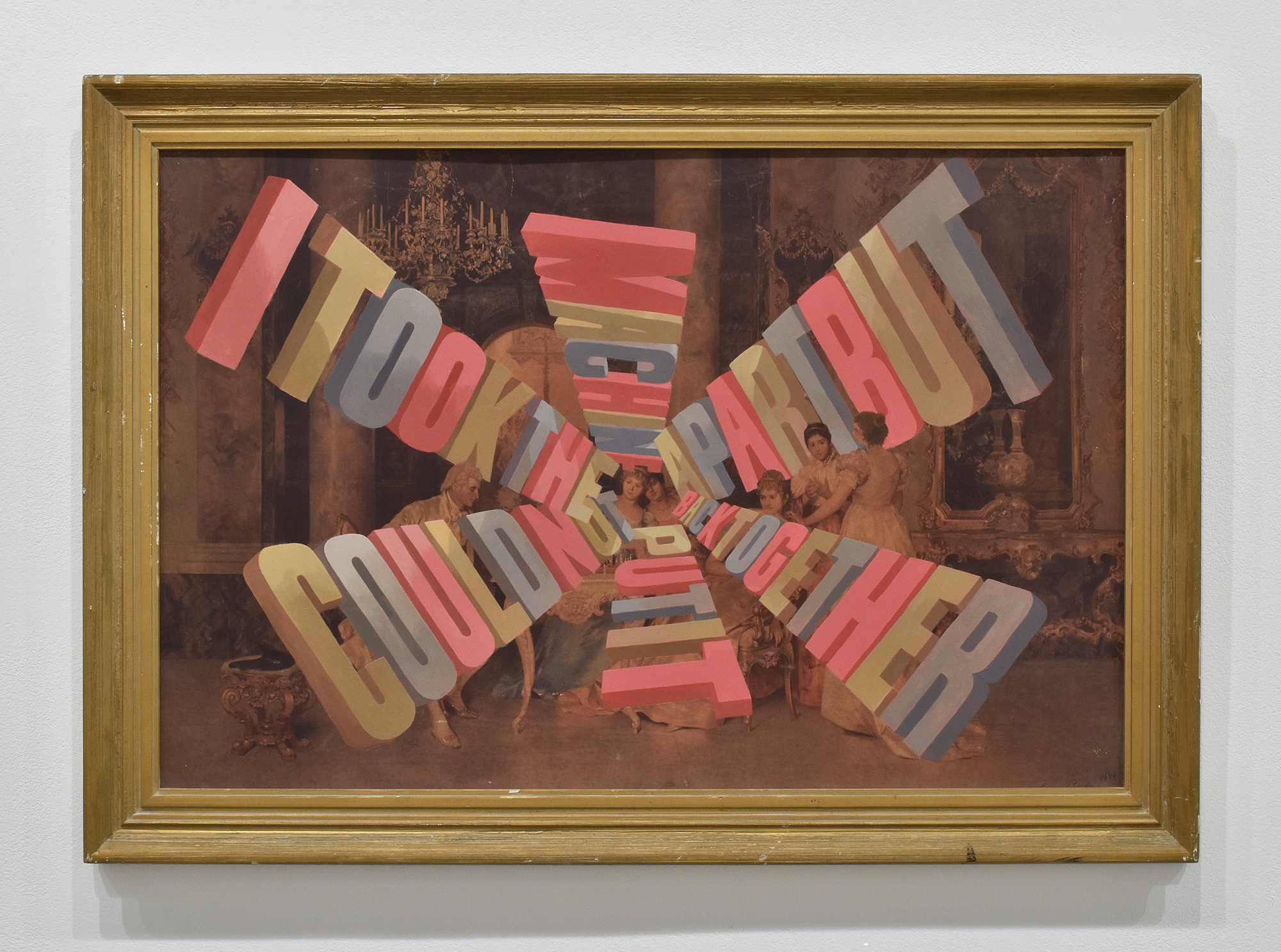

I TOOK THE MACHINE APART BUT COULD NOT PUT IT BACK TOGETHER, 2017, acrylic on vintage offset lithograph by Wayne White. Courtesy the artist and Joshua Liner Gallery

Nudes, dogs, landlords, saints. Until the nineteenth century, the landscape was merely a functional backdrop for more important, “elevating” subjects, if not a means of topographical study. Adopting Edmund Burke’s theory of the sublime, and spurred by the transcendental philosophy of the Romantic movement, landscape painting began to reflect a self-sustaining energy, whereby Nature, in its scale and range, its complexity and harmony, offered proof of a divine power. The tradition in America owes its seriousness to Thomas Cole and his successors—Asher Durand, Frederic Church, Albert Bierstadt, et al.—whose work provided the means by which the American wilderness was transmogrified from the primitive, dangerous otherness of Puritan imagination into an aesthetic touchstone, a symbol of the aspirations of Americans themselves.

Wayne credits these painters as important influences, but, like any good artist with eclectic interests, draws from a wide range of other sources: Marcel Duchamp, Edward Hopper, Winslow Homer, Thomas Eakins, Francis Picabia, Stuart Davis, Edwin Dickinson, Bruce McCall, Philip Guston, Robert Crumb, Ed Ruscha, Jack Cole, Ralph Steadman, Charles Burns, Elizabeth Murray, Mark Tansey, David Salle, Neo Rauch, Ad Reinhardt, Roy Lichtenstein, Claes Oldenburg, Max Ernst, Paul Rand, Tex Avery, Winsor McCay—to start with. This range can be distilled when sieving each painting’s curious elements: the tight phrasing (from years of inching ideas into comic thought-bubbles), and their confessional tone (ditto the comics tradition); the reverence of Nature; the fact that the landscape itself is borrowed—not famous, but nearly anonymous, in the same “ready made” spirit in which Duchamp stuck a bicycle wheel on a stool, signed it, and called it art; the exploration of language as an aesthetic object (Ruscha's famous turf)—all of it mixed together with a crazy, disciplined joy.

It is difficult to imagine an artist investing so much effort in knockoffs of the very thing he aims to perfect, but Wayne insists that his affection for these kitsch arcadias is genuine. “I was interested in this element—big, beautiful landscapes and such. People call it kitsch. I’m often saddled with that term, and I guess I was asking for it. But I don’t really see them as kitsch; I don’t really judge them like that at all. And I'm not trying to be snarky about it, either. There’s simply an element there that’s up for grabs. Plus, these paintings are so ubiquitous. That’s one of the reasons why people have been so responsive to them. Everybody has a personal association with these pictures. They were either at grandma’s house, or your aunt and uncle’s house, or in your own house or your friends’. They’re everywhere. So I’m definitely more interested in what they share than in their differences.”

Throughout his body of work, the secondhand landscapes have remained consistent, while the text has evolved in complexity, through three phases: sentences running along a straight trajectory, or curved, exiting stage right or left, or coming in from the void; words of the same scale but now creased or bent, like damaged cardboard displays; entangled abstractions, loose, Cubist, or like Constructivist sculptures scattered over a beach, the long leg of a T drooping over a rock. The frustration in reading these is like trying to decipher a vanity plate, and often I’ve given in to simply reading the painting holistically, enjoying the bewilderment they trigger, the trompe l’oeil confusion over how a tangled, alien declarative cooperates with a view of Mt. Shasta, or with a glen.

But why these particular paintings? Why not, say, more Abstract or Expressionistic landscapes, something less kitschy, or even something closer to Ruscha's atmospheric backgrounds? “Well, you do have to go through Ruscha any time you use words in painting. But I’m interested in something else, thematically; and on a technical level, all these paintings gently lead your eye into the composition. The foreground and middle ground are always wide open, so your eye follows this visual path. There’s literally this lane of space where words fit naturally. It’s an old trick, a restful-eye trick. All the complications are at the edges, and you serenely float through this space. There’s nothing jarring or jagged. It’s an unencumbered space in which to put some structure. It all fits.”

This still leaves the question of kitsch’s inscrutable appeal. Perhaps it resides in over-precision. One hardly criticizes abstract work as kitschy. It could be that the confluence of beautiful phenomena is an obvious stacking of the deck. A waterfall or two, or three, foregrounding a snow-capped mountain and a sparkling stream accented with wildlife...one might as well paint a unicorn with doe eyes, its white flanks brushed with moonlight. A grotesque example, but the proliferation of this and other schmaltz does suggest a profound cultural impatience; that these shortcuts attend to deeper needs, not the least of which is the close proximity to beauty, however we can get it.

War came to Chattanooga, and here on Lookout Mountain, just on the other side of Rock City, you get a clear sense of the staggering advantage General Bragg had over Hooker’s Union army scrambling in the valley below. Bragg’s unraveling was hidden in the weather, in a cloud cover that shrouded the valley now and then, and which appeared on the morning of November 24, shrouding Hooker’s position below. The fog stuck, and you could imagine Hooker’s tactical wheels spinning and the sick panic Bragg must have suffered upon discovering, once the haze had evaporated, that Union troops had advanced far enough up the mountain that the cannon couldn’t get an angle on them. By morning of the next day, Hooker had taken the mountain.

An embarrassing loss, sure, but with all the doodads for sale at the gift shop here, celebrating the Battle Above the Clouds, you had to wonder: What other political entity gets so much mileage out of defeat? Chattanooga makes good money off Bragg’s gaffe, making the battle for Chattanooga seem almost, well, romantic. The view helps, of course.

Our trip to Lookout Mountain got a late start, and once Wayne and Mimi and the kids picked me up, there were a few sights to squeeze in on the way: the tow-truck museum, the Chattanooga Choo-Choo, and, at the base of Lookout Mountain, the World’s Steepest Passenger Railway—a slow train that hauled you up the mountainside at a sickening angle.The stops at each were brief if they occurred at all; Wayne wanted to reach the summit to show me the vista.

In the car, I saw his sketchbook there on the console between us, and he let me snoop through it, just a pocket-sized thing with phrases scratched in it: WONDERFUL ORGANIZATION; STILL HOT; FUNNY ART IS NOT FUNNY; HE DIDN’T TAKE IT TOO GOOD; KUMPUTERS; YOU HAVE TO BE STONED TO GET INTO IT; WE WERE IN AWE OF HIS WORK BUT HE WAS A GIANT ASSHOLE; THE RIDICULOUS FLOWERS OF MANHATTAN; ONE AS SENSITIVE AS I FORCED TO DO THE THINGS I HAVE DONE; including a handful that seemed to get away from him: I TOOK THE MACHINE APART BUT COULD NOT PUT IT BACK TOGETHER AND WAS FIRED; HE STARTS IN ON THAT BUSINESS ABOUT THE PASSIONS OF THE SHAMAN AND THEN HE GRABS THE KEYS TO THE DODGE AND HE’S GONE; WHEAT TOAST, CAR KEYS, ETC.; WE’RE OVER HERE PERCEIVING THINGS AT THIS REALLY HIGH LEVEL AND NOBODY SEEMS TO CARE.

I asked if this was a first-thought-best-thought process. “Some are. Some are very spontaneous. Some come up in conversational bits. Some just come full-blown out of the air. And some of them I work over like any writer would—boil it down and boil it down and boil it down.”

What threaded them together? “I couldn’t really sit down and write a thesis about it or anything, but I think one of my themes is vanity. Human vanity is hilarious; the ego is hilarious. That’s one of my ongoing obsessions, trying to get humor into fine art, because it’s very, very rare, and I see it as open territory. Sort of an unplowed field that I can go to. They’re almost, like, antithetical to each other, you know?”

I looked up at the houses gliding by. We kept making sudden turns. Predictably, despite the signs and painted arrows, Wayne just couldn’t find that one crucial turn that would lead us to the entrance to the park.

“That’s a big can of worms about humor and art,” he said, “because most people want their artists to be like these suffering saints. They love crazy, suffering madmen. Jackson Pollock, Vincent van Gogh, Jean-Michel Basquiat. They all suffered and died for their art. That whole suffering-saint thing still hangs real heavy over picture making, and its just more nineteenth-century Romantic silliness.”

We twisted up the mountain; the houses improved with the elevation, though we saw several of them twice. “There’s that girl again,” Lulu said, and yes, there she was a third time. Harley conventioneers were beehiving all over the mountain on those farting, abominable machines that fouled-up the solitude. Wayne moaned and squinted; the maps were smoking apart in his mind. “Why don’t you turn right here?” Mimi said, down a street we’d followed already but had given up on.

Prematurely, since we shortly found the entrance to the park. It was full of bikes, of course, a long line of them leaning at precarious angles, begging for a push.

Though cooler up here, you were still fair game under the sun. The only shade, really, was along the ledges. And the air was thinner. We had the family’s pace, slow, dislodged, confused, and made our way carefully along the stone steps to where the cannons were, and peeked over the edge and marveled at how awful and awkward the close combat must have been, at how one could gain any advantage with a rifle while having to clutch a limb on the side of a rock to keep from falling off. We took pictures; the river glistened.

It really was breathtaking, the panoramic spread of the city and woods. You could see the peninsula that sheltered the psychiatric hospital, and it was tempting to try to imagine the land without so much of the man-made stuff, in its virginal purity, and perhaps the flora below would’ve been brighter without all the haze interfering. One of those phrases kept appearing—WONDERFUL ORGANIZATION—curving across the valley, dipping into the river. The geometry suggested a higher mathematics.

The kids were getting restless. We took a few more pictures and headed toward the gift shop, where we found replica Civil War pistols, replica swords, Johnny Reb bobblehead dolls, a tub of old crock marbles. I bought a small birdhouse with SEE ROCK CITY painted on the roof. The family was scattered about, and Wayne called me over to where he stood by a door, and led me through it into a dim, cool space with a dozen pews that faced a mural—James Walker’s thirteen-by-thirty-foot rendition of the battle of Lookout Mountain, which Hooker commissioned, and which Walker began to sketch as the fighting was taking place. The thing was marvelously detailed, almost microscopic, but overwhelming up close. So we found our separate spots in pews on opposite sides of the room, and stared at the battle, mesmerized for several long, peaceful minutes.

“It’s such an audible painting,” Wayne said. As if on cue, a kid slipped in and pushed a button on the wall, triggering an audio lecture, its narrator interrupting the lovely, reverent silence. The painting seemed to shrink a little.

“There’s this painting in Atlanta,” Wayne said, “the Cyclorama. It’s this gigantic painting in the round, three-hundred-sixty-five degrees, depicting the Battle of Atlanta. Not many people talk about it. It’s got all these little diorama elements in the foreground, little soldier figures and bushes and artillery that all blend in perfectly with the painting as it recedes. We’d visit it all the time when I was a kid, whenever we passed through Atlanta. We’d go there and the zoo, to see a gorilla named Willie B. He was a hit. He died a while ago.”

“You should do one,” I said. “A cyclorama.”

He seemed distracted, daydreaming. “I’ve been thinking about it.”

Mimi walked in, the kids in tow. They looked frustrated and bored and sweaty; the trip had worn out its excitement. It was time to go home.

HOONOO, 2017, acrylic on inkjet print on canvas by Wayne White. Courtesy the artist and Joshua Liner Gallery

The Whites—Willis, Billie, young Wayne and his sister, Melissa—were the first family to build on their street, a planned neighborhood on the outskirts of Hixson that at the time was still woods and fields and just a farm or two. Now it’s typically suburban, the houses all akin to the ranch style, middle-class, nothing flashy. The only anomaly, really, was suggested by the White’s side yard, which had an excessive amount of lawn furniture, a birdhouse, a bird bath, some bicycles. We were walking around, and Wayne made a wide, sweeping gesture to show where the tree line marked what was once all woods. He talked about the thrills of growing up here, the decrepit, century-old log cabin tucked way back in those woods, which he found creepy and fascinating, and, in particular, a house long gone that used to be down the street, where a couple and their blind daughter had lived, but which the neighborhood kids thought was haunted after the family moved away. Wayne remembered invading the house and discovering all the Braille books the family had left behind, and, after a flood, the dozen or so paint cans that were floating in the living room. “Better than anything they can come up with today, man.”

He was feeling giddy. We cut through the yard and made our way to the porch, where the stuff scattered about was a prelude to the house’s clutter: dollhouses, birdhouses, statuettes of dogs and ladies, various baubles, a washstand, rifles, pistols, photos, farm equipment. (It was pointless to try to catalogue the garage.) Here, he said, was the antecedent to Pee-wee’s world, and you could clearly see the same friendly mania that was projected through the set.

Everybody was wiped out. Lulu and Woodrow moved to the kitchen table to resume a game of checkers they’d abandoned for our field trip. Wayne’s parents hosted us in the living room, and we enjoyed some small talk, and they shared a few stories of their courtship and Willis’s brief, scary time working for his father-in-law. Mrs. White showed me Wayne’s first painting, too, which hung above the sofa, a portrait of himself and his sister. Woodrow and Lulu were concentrating. There was a family vibe. We drank water. Everywhere you turned, there was some strange object that surprised you.

And then Wayne gets up and reaches behind the sofa. “One more thing,” he says. I’m thinking he’s going to fetch a puppet from the old days, but instead he pulls out a banjo, sits on an egregiously decorated recliner, and starts ripping through a rendition of “Foggy Mountain Breakdown,” all in one fluid motion, no introduction. I’m exhausted, and this sudden plucking is too much to process, and I can only sit and listen, dumbfounded. It just so happens that John Hartford, who famously picked this song as well as “Gentle On My Mind,” and who also happened to be a longhaired riverboat captain on the Mississippi River in the 1970s, is another hero.

Wayne, my God, he plucks like firecrackers! I notice the statue of the Doberman next to him, sitting attentively above the statue of the frog, and slip into a nostalgic warp: For years I could’ve sworn that, as a toddler, my best friend was a beagle, always calm, very attentive, and only when I was sixteen or so, rummaging through old photos for something else, and seeing a picture of us together, did I learn the dog was made of porcelain, never alive. This truth was cold and indisputable. It proved that the pattern of dogs entering and abruptly exiting my life (four so far) reached back to infancy—and worse, that my mother has a thing for fake dogs (her latest is a golden retriever made of wood). This really has nothing whatsoever to do with what’s happening in the living room, it’s just an uncontrollable memory breach. But it produces a Zen-like sensation of communion with the artist, the past alive and loud and in full color. We are surrounded by decades of attachment reflected in wild, animated crap, in toys and tools and art. He picks up speed, pinching that banjo so fast that I worry he might flub the song, but he doesn’t, and the tension is thrilling, the nostalgia is thrilling, and amid this din it becomes clear: Sure, the boy dragged himself out of Hixson, but Hixson still won’t leave the boy alone. Crazily, this is how he likes it.