© Nathan Alexander Ward

Fog Count

By Leslie Jamison

It’s early morning and I’m hunting for quarters. Downtown Fayetteville is quiet and full of stately stone buildings: mining money, probably. We’re in the heart of coal country. The corner diner isn’t open yet. The “Only Creole Restaurant in West Virginia” isn’t open yet. City Hall isn’t open yet. One of its windows displays a flier raising money to build a treehouse for a girl named Izzy.

I’m looking for quarters because I’m headed to prison, and I’ve been told they will be useful there. I’m going to see a man named Charlie Engle. We’ve been corresponding for the past nine months. He has promised that if I bring quarters we can binge on junk food from the vending machines while we talk. Visiting hours are 8 to 3. It makes me nervous to think about talking from 8 to 3. I’m afraid I’ll forget all my questions or that my questions are wrong anyway. I’m plotting my meals in advance: vending machine breakfast, vending machine lunch. I’m already thinking about what I’ll do—what I’ll eat, who I’ll call, where I’ll drive—once I’m out.

Charlie and I met two years ago at an ultramarathon in Tennessee, several months before Charlie was convicted of mortgage fraud and sentenced to twenty-one months at the Federal Correctional Institution (FCI) Beckley, in Beaver, West Virginia.

Charlie is a cat of many lives: once-upon-a-time crack addict, father of two, professional repairer of hail damage, TV producer, motivational speaker, documentary-film star, and—for the past twenty years—one of the strongest ultra-distance runners in the world. Charlie started running in eighth grade: I was awkward and gangly and self-conscious pretty much all the time, except when I was running, he wrote to me once. Running made me feel free and smooth and happy.

Charlie’s accomplishments are well-known in the ultra-running community: he’s run across Death Valley; he’s run across the Gobi; he’s run across America. He has trekked hundreds of miles through the jungles of Borneo and even more through the Amazon. He’s climbed Mt. McKinley. In 2006 and 2007, he ran 4,600 miles across the Sahara. The journey was documented in a film and it was this film, incidentally, that set his legal nightmare in motion.

The story of Charlie’s arrest and conviction is long and harrowing, but here are the basics: an IRS agent named Robert Nordlander started wondering about Charlie’s finances after watching the Sahara film. He wanted to know: how does a guy like that support all his adventures? I’ve tried to understand Nordlander’s curiosity as vocational instinct. Perhaps he wonders how strangers pay their taxes the same way I wonder how strangers get along with their mothers, or what secrets they keep from their spouses.

Nordlander opened an investigation, and he didn’t find anything wrong with Charlie’s taxes. But instead of closing the case, he pushed further. He authorized garbage dives. He authorized tactics that wouldn’t have been possible before the Patriot Act. He started looking into Charlie’s properties. He sent a female undercover agent—rigged with wires—to ask Charlie out to lunch. Charlie was single at the time. He said yes. He tried to impress. He said his broker had filled out a couple “liar loans”—standard shorthand for stated-income loans—and that non-confession pretty much sealed the deal. In October 2010, Charlie was convicted of twelve counts of mail, bank, and wire fraud. Nordlander had won his case at last.

Charlie’s case was also part of a much larger story: the fallout of the American subprime mortgage crisis. His conviction, one imagines, was largely fueled by the general knowledge that things had gone terribly wrong and the sense that people should be held accountable. So Charlie was held accountable. He was held accountable for something millions of people did, something he still alleges—with compelling evidence—he didn’t do. He became a convenient scapegoat for the inevitable collapse of a system fueled by recklessness and greed.

At the time of his arraignment, Charlie was engaged. His engagement didn’t survive the trial. He was imprisoned a state away from his teenage sons in North Carolina. He lost his corporate sponsorships. He lost two years of racing. He lost the right of motion. He lost—as he’d tell me later, quite simply—a lot.

I first wrote Charlie a letter because I was fascinated by his life. It gave me a sense of vertigo to know that when we’d met, in the hills of Tennessee, he’d had no idea what was about to happen, how everything was going to change. I wondered what incarceration was like for him. Running made me feel free and smooth and happy. His body was a body that found solace in moving itself across territory—across deserts and jungles and entire nations. The core of his life pointed its finger at the very fact of what incarceration does, which is to keep someone in one place. I wanted to know: what happens when you confine a man whose whole life is motion?

One thing that happens is you turn him into a good pen pal. Over the course of our correspondence, Charlie was smart and funny and honest. He steered himself away from anger about his incarceration, but he did so with such intentionality, such earnest and visible effort, that the anger itself emerged as a negative shape carved in the margins. Charlie described it as a cliff; he had to pull himself back from the brink. My anger is immense and I hate the feeling that I am losing control, which happens mostly when I let that anger breathe. He looked for what he could salvage: Like all difficult things, if we can remain open ... something positive will come. That said, I am still a bit baffled about what good will come from this for me. I lost a lot.

He wrote about his mother, who was slipping into dementia: I miss her. I can say that it’s unfair for me to be away from her and it would be true. He wrote about women: I have never gone this long in my adult life without sex. I don’t think I could have ever gone a year alone out there.

“Out there,” incidentally, was a phrase I heard frequently at the Barkley Marathons, the ultra-run where I first met Charlie. It’s a brutal race through more than one hundred miles of briar-studded Tennessee hills. At Barkley, “out there” meant in the wilderness, on the course, getting lost or getting found or whacking your way through underbrush. “Out there” meant you were in motion, doing the thing, winning or getting beaten. “In here,” in prison, was the opposite of all that; it was never getting lost, never going where you hadn’t already been.

Some weeks Charlie’s letters were written from a low-down place: My mother is getting worse, my knee is getting worse, my attitude is getting worse. Or: Today I awoke full of fear.

He was forced to stop running on the prison track because of an injury that turned into a Baker’s cyst, a huge swelling behind his knee. He wrote about the incredible frustration of trying to get treatment: I have spent more than 90 days just trying to see the doctor. The neglect here is almost unimaginable.

At Christmas, he sent a photocopied cartoon: a bearded Santa behind bars staring at a puny tree. “Wish You Were Here” was crossed out and replaced by “Wish I Was There.”

Writing to Charlie often made me feel guilty. I wrote about something as simple as walking around my neighborhood, with its methadone clinic and its blossoming pear trees, and felt like there was no way to communicate my world to Charlie that wasn’t rubbing salt into the central wound of his life. I wrote about running in the rain—by the end I was so soaked I didn’t even feel separate from it—and how running in New Haven rain reminded me of running in Virginia rain with my brother, past a fish factory on the Chesapeake, after our grandfather died. Maybe I’m an asshole to write to you about running, I wrote, but sent the letter anyway. I thought it might connect to something Charlie had mentioned about running around the prison’s gravel track during a storm. It was the best time to run, he’d written, because everyone else went inside. It was the only time he got to be alone. Talking on the phone with Charlie was even stranger: a voice announced, at even intervals, You are talking to an inmate at a Federal Correctional Facility, and I walked down Trumbull Street in the twilight while he sat somewhere—in a little plastic booth? I couldn’t even picture it—and when we got off the phone, I ate roasted trout at the nicest restaurant in town while he headed off for another stretch of top-bunk reading into the late night.

I liked when we wrote about the past, because it meant we were on equal footing—or rather, he had more past than I did. As he put it, more life experience under his singlet. We both wrote about drinking and using, and stopping drinking and using. Charlie wrote about being an addict with twenty years of sobriety in a prison where he suspected no one else—out of more than four hundred men—had gotten clean before arriving. In his twenties, Charlie ran a hail-repair business that took him all over the country—chasing nasty weather and its comet trail of damage, chasing eight balls in the worst neighborhoods of shitty Midwestern cities. He hit bottom getting shot at by angry dealers in the wrong part of Wichita. He would have gotten more time for what he was guilty of back then than he got for what he’s innocent of now.

I wrote about the one-legged traveling magician I’d met in Nicaragua, years before, who was a drunk and whose drinking made me unspeakably sad; how I thought of him years later when I tripped, drunk, on a pair of crutches of my own. I wrote about trying to take a girl, newly sober, out to a raptor refuge near Iowa City—to see the wounded owls! I’d promised her, as if these broken birds were some wonder of the world—and how I’d gotten lost, and driven in circles until we finally sat on a bench smoking cigarettes instead, and how I felt like a failure because I wanted to make sobriety seem full of possibility but instead I’d made it seem full of disappointment.

For a week, in the spring, Charlie and I wrote letters every day. We made a ritual out of noticing. We focused on particulars. He described an argument about an unpaid debt, a bigger guy approaching a smaller guy: “Blood on my knife or shit on my dick, I will collect what I’m owed.” He wrote about the evolution of his Fridays: draft beers for a quarter in his drinking days, prerace rest days in his sobriety. In prison they were something else entirely: Every Friday for 15 months, lunch has been a piece of square fish of unknown origin, along with too-sweet cole slaw and potato chips I won’t eat. Friday means very loud inmates late into the night, playing cards or dominos. Fridays mean there will be another movie shown, a movie I refuse to watch because I never want to even pretend that I am comfortable here.

Charlie wrote about buying FireBalls and instant coffee at the commissary, about the correctional officer at lunch who yelled when inmates couldn’t decide quickly enough between cookies and fruit. He described how Beckley felt on Mother’s Day: Mother’s Day creates a prison full of zombies, walking around in a daze, hoping the day passes quickly. Mother’s Day reminded those men of how they were failing to be sons. Every holiday was an invocation of “out there,” the life none of them were living.

Charlie invited me to come visit. He put me on his visitation list and told me the rules: You probably shouldn’t wear Daisy Dukes or a tube top. Also best not to bring in drugs or alcohol. A woman once came in a skirt without panties. She was, he wrote, visiting a very young man with a very long sentence.

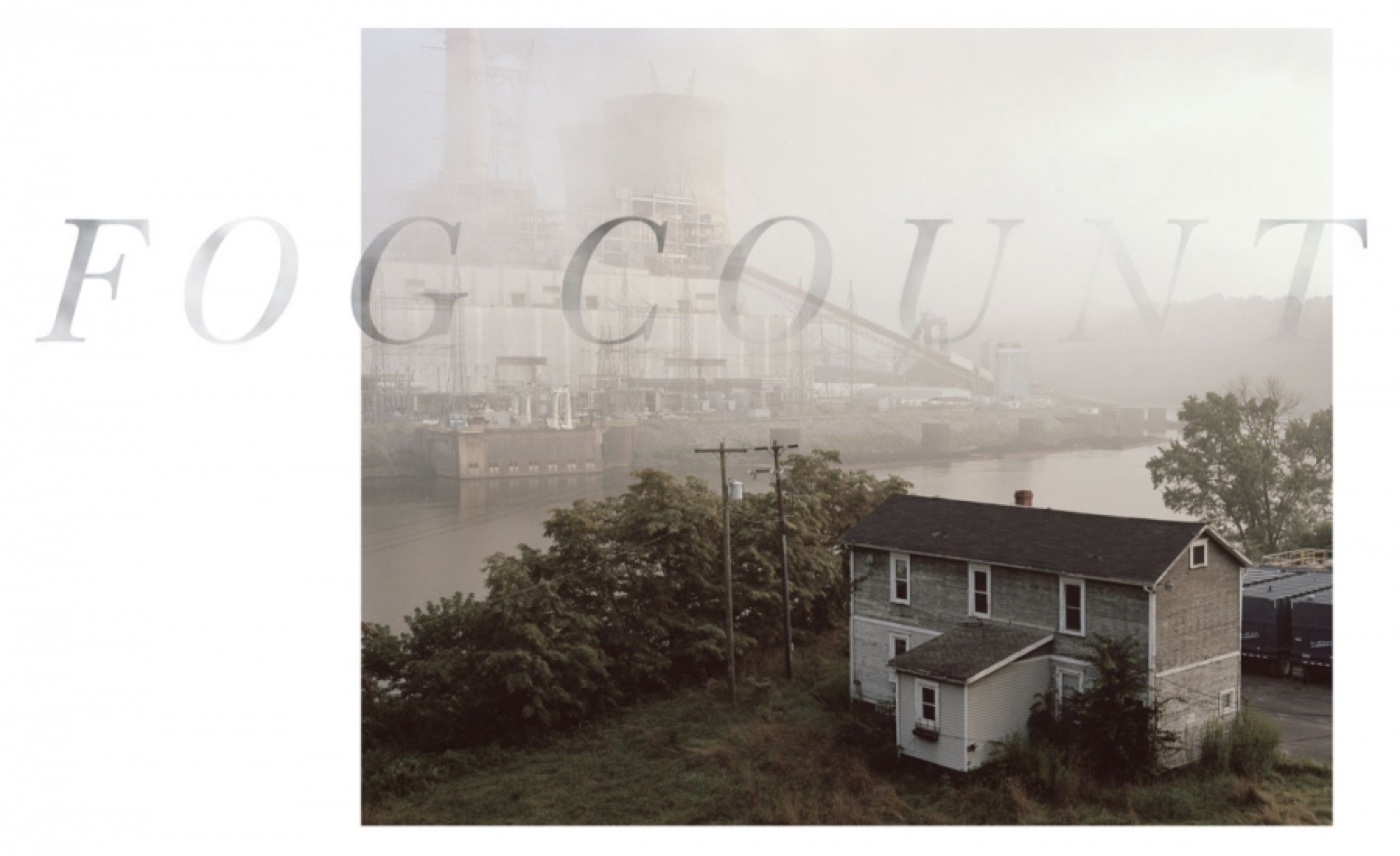

I found more guidelines online: I wasn’t allowed to wear camo gear or spandex or green khaki that looked like Beckley khaki, or boots that looked like Beckley boots. If there was too much fog, I might get turned away. Beckley gets strict in the fog. The inmates get counted more often. I pictured this fog—this mythic, West Virginia fog—in vast, billowing ripples, fog so thick a man could ride it to freedom like a wave. Every fog count is an act of protest against unseen possibility; Beckley clutches men close—tallies them up, keeps them contained, seals them off.

I found the commissary sales list online in a grainy pdf. You could get Berry Blue Typhoon Drink Mix, Fresh Catch Mackerel, Hot Beef Bites, or a German Chocolate Cookie Ring. You could get Strawberry Shampoo or something called Magic Grow or something else called Lusti Coconut Oil. You could get mesh shorts or a denture bath. You could get Religious Certified Jalapeño Wheels. You could buy Milk of Magnesia or Acne Treatment or Prayer Oil.

I found rules. There were rules about movement and rules about hygiene and rules about possession. Too many possessions could be a fire hazard. You were allowed five books and one photo album. Hobby craft materials had to be disposed of immediately after use. Finished hobby crafts could only be sent to people on your official visitation list. There would be no postal harassment by hobby craft.

I saw what happens if you follow the rules: there wasn’t just basic didn’t-fuck-up official Good Time (Statutory Good Time) but also Extra Good Time, further divided into Industrial Good Time, Community Corrections Center Good Time, Meritorious Good Time, and Camp Good Time. Camp Good Time. Not really.

"Original Site of Execution via Electric Chair, West Virginia" (2011) © Emily Kinni

"Original Site of Execution via Electric Chair, West Virginia" (2011) © Emily Kinni

Heading south down I-79, I feel the border between Maryland and West Virginia as smooth highway turning to sandpaper. The land is beautiful. Really beautiful—endless lush forests, pristine and unblemished, countless shades of green on hills layered back into drifts of fog. I start thinking maybe coal mining is just a notion someone had about West Virginia; or something they like to talk about on NPR. Maybe it’s just a theme for the twisted-steel sculpture garden I see to my left—Coal Country Miniature Golf—and not an actual series of scars in the earth. Because this place seems phenomenally unscarred, phenomenally pure. Freeway exits promise beautiful, luminous places: Whisper Mountain, Saltlick Creek, Cranberry Glades.

I spend the night with Cat, a friend from college, who covers Fayette County for a local paper. Cat lives in a ramshackle house strung with Mexican fiesta flags and skirted by an apron of oddly comforting debris: a pile of old dresses, a bucket of crushed PBR cans, an empty tofu carton with its plastic flap crushed onto the dirt. Cat lives there with her boyfriend Drew—a veteran of anarchist communal living who now works deconstruction and salvage, taking apart empty homes and selling their flooring to hip bars in northern states—and Andrew, a community organizer who works on land reform.

Their home reveals itself in dream-like pieces: a pile of crusted dishes, a bone on the floor, a giant spider lurking in a white ceramic mug, a fabric owl covered in sequins, a square of vegan spanakopita catching fire in the toaster oven, a dog to whom the bone belongs, a creek out back and a giant slab of rock for sunning and a garden too, full of beets and cabbage and spinach-for-vegan-spanakopita and blossoming sweet peas curling up wire lattice and even the tiny, barely sprouted beginning of a pecan tree.

I sit with Cat and Drew in a cozy room, under a bare yellow light and its fluttering density of flies and moths. A tiny flying thing dies in my spanakopita. I ask Cat what she writes about for her newspaper. She says one of her first stories was about Boy Scouts. Leaders in southern West Virginia fought hard for the Boy Scouts to locate a new retreat center here. They offered to build roads. They offered tax breaks to local contractors. They were eager for an industry that wouldn’t involve plundering the land.

The Boy Scouts built their retreat on an old strip mine. When Cat was interviewing the flocks of scouts who came to clear trails, she asked if they knew how surface mining worked—the blasting of entire mountaintops, the razing-bare of the earth, the turning of forest into dirt-brown vistas. The Boy Scouts didn’t know. They were horrified. But why would you—? That’s when a bigger Boy Scout arrived. A Boy Scout in charge of other Boy Scouts. He said the conversation was over.

Cat and Drew tell me how to pronounce Fayetteville—like Fay-ut-vul—and they also tell me about bigger stuff, like how most of West Virginia’s forest has been cleared at some point since the 1870s—in multiple waves—for the sake of salt and oil and coal and lumber and gas. But it looks so green, I say. I tell them about my drive south—those lush hills, their lovely curves receding into the middle distance.

Drew nods. Yep, he says. There’s no surface mining near the highways.

Potemkin Forests! I feel like an idiot. Cat tells me to look out for what they call beauty lines—rows of trees planted along hill crests to mask the vast moonscapes of mine-ravaged land beyond. I am one of the Boy Scouts. I am being told about the wrongness right in front of me. Drew says that some of the land here has been mined so much it’s essentially on stilts, barely holding itself up. They call this land honeycombed. West Virginia is like a developing nation. It has so many resources and it has been screwed over again and again: locals used for labor; land used for riches; other people taking the profits.

How can I explain the magic of that house? It was a paradise on damaged land, with its fiesta flags and its flutter of moths, its sequined owl and mounds of embryonic squash rising from whatever earth was left between the stilts—and Drew and Cat so full of goodness, their nerves so awake to this world, explaining it so patiently, inhabiting with utter grace their small fraction of a torn territory.

In their hallway the next morning, I find a different dog than the one I saw the night before. This dog seems friendly too. I don’t feel like I’ve gotten much sleep but I can remember what I dreamed: I was interviewing a man in a dingy diner and I had just gotten through my chitchat questions and was preparing to get into it—though I wasn’t sure what “it” was—when the man rose to pay the bill. I woke with a feeling of panic: I hadn’t asked any of the questions that mattered.

It’s a dream so obvious I feel betrayed by it. It neither dissolves an extant fear nor illuminates a new one. It simply tells me I’m afraid I’ll say stupid things (as I’m always afraid of saying stupid things), that I will ask questions that are beside the point, that my curiosity will prove little more than useless voyeurism, a girl lifting her sunglasses to peer between the bars, stuttering What’s it like here? What part hurts the most?

I end up finding quarters in a coffee shop tucked under the gray stone wing of a church. I drive to Beaver. I watch for beauty lines from the highway. I can’t pick them out, which I suppose is the point. NPR runs a segment on rural schools in dirt-poor mining counties, while local radio plays advertisements from mines looking to hire.

Mining and incarceration are both looming presences on the West Virginia landscape—both willfully obscured and misrepresented, their growth slopes neatly inverted. Mining is an industry in decline; incarceration is on the rise. The number of inmates in West Virginia has quadrupled since 1990. People with political influence and powerful economic interests allow the state to be exploited by new industries in order to repair the damage old industries have caused.

In the false American imagination, West Virginia is a joke or else it’s a charity case; but more than anything it is unseen, an invisible architecture of labor and struggle; and incarceration shares this invisibility, hidden at the center of everything; our slipshod remedy for an abiding fear, danger pinned to human bodies and then slotted into bunk beds you can’t see from any highway.

© Nathan Alexander Ward

© Nathan Alexander Ward

Charlie is one of these bodies. His story is the story of a system that strip-mined the American housing market and peeled away whatever it could, leaving the economy on stilts—land on stilts, subprime-hollowed earth—and balancing an impossible future on dreams and greed. Now we try to live in the aftermath. We punish where it’s possible. We take a systemic tragedy and turn it into neatly packaged recompense: time served.

I follow my GPS to 1600 Industrial Park Road. I don’t make a right turn into Beckley or a left turn into Beckley. The road simply becomes Beckley. I pass an empty guard’s hut and find myself curving between strangely manicured banks of lawn and clusters of forest that remind me of nothing so much as a country club.

I do everything wrong.

First, I go to the wrong prison. FCI Beckley consists of two facilities: a medium-security prison and a lower-security Satellite Camp. I know Charlie is housed at the Satellite Camp—along with the other minimum-security guys, mostly there for drugs or white-collar crimes—but for some reason I think I still have to get processed at the main building. This is not the case. The guard on duty shows his irritation at my ignorance. Before we discover this large mistake, however, he has the opportunity to point out smaller ones: I’m carrying my purse. We’ll need to put that in a locker. I’m wearing a skirt. He was a very young man with a very long sentence. I want to tell the guard: “My skirt is long! I’m wearing underwear!” I feel my body as an object and agent of violation. I feel suspected and imagined.

I fill out a visiting form alongside an elderly couple. I notice the woman has a plastic baggie full of quarters and dollars; I feel a kind of kinship. She is also looking ahead to the vending machines—has come prepared to offer her son snacks, at least, and company, if she can offer him nothing else.

I wait while the guard gets off the phone. It seems like he’s talking to someone who is about to check himself in. “Self-surrender?” The guard says into the receiver. “You can bring a Bible and your medications.” Strange to imagine a man at home, or wherever he’s calling from, being told the terms of how he will be systematically stripped of almost every possession, a thousand freedoms.

Once he gets off the phone, the guard resumes telling me things I have messed up: I don’t have Charlie’s number written on the form, because I don’t have it memorized. But he can look up his name, which I have also spelled wrong because I’ve gotten so flustered, and that’s when the guard tells me I need to go back down the road to the Satellite Camp.

At the Satellite Camp, the guards are nicer, but I am still doing things wrong: I park on the wrong side of the lot. I still have my purse and I need to put it in my car. I feel like saying: But up there they had lockers! I want to show off my knowledge of something. Anything. My purse is a black canvas bag with a yellow dinosaur on it. Officer Jennings is almost ready to make an exception. “A dinosaur exception,” I say. Jennings likes this. The guys down here at the Satellite Camp seem open to speaking this way—as humans, joking around. Jennings asks me whether Charlie ever got that cyst drained. I say I’m not sure. I have also failed at being a good pen pal.

I hear them call Charlie’s name on the loudspeaker. I am thinking of all the families who never mess up anything, who’ve got the routine down cold, have its every motion committed to muscle memory. There’s a certain heartbreak in knowing this minutiae so well: the inmate number, the plastic bag of quarters, the jeans and the hard chairs and the faces of the guards, each one’s particular tolerance for humor, the twist and curve of the roads, the eventual selection of barbecue chips or gummy fruit snacks; the motions of greeting and exit, how you might carry yourself differently saying hello and saying goodbye.

Charlie stands at the visiting room entrance: a handsome man nearing fifty with short silvering hair. He’s wearing big black boots and an olive uniform, his number printed over his heart. I’m not sure about the rules. Can we hug? Turns out we can. We do. But there are other rules: Charlie isn’t allowed to use the vending machines, only I am, so he has to tell me what he wants; and we’re not allowed to sit next to each other, only across from each other, for reasons I’d rather not consider. When I look at all the chairs arranged around the room I see there is often one singled out, apart from the others: the inmate’s chair, facing everyone.

Over the course of our visit, my Fay-ut-vul quarters buy us the following: a block of peanut-butter cheddar crackers, a bag of M&M cookies, a bag of Cheez-Its and one of Chex Mix, a Snickers bar, a huge “Texas”-sized cookie as big as a child’s face, a Coke, a Diet Coke, and two grape-flavored waters—the second one a mistake, or else a free gift to me from the Bureau of Prisons. Our table turns into a miniature landfill.

It’s a Monday, not a weekend, so the visiting room isn’t crowded. Nearly everyone stays until three. We’re an ecosystem. The family sitting next to the vending machines reminds me to take my leftover twenty cents. Two little girls are obsessed with the thin line of ants near the window. One of them starts telling Charlie about a sorcerer, and something about her birthday, a monologue that remains largely unintelligible until she pauses to say, quite clearly: “I hate evil.”

Charlie says, “I do too.”

When these girls first came in—with their pretty, dark-haired mother—Charlie told me he heard their father got reduced time for telling on an innocent man. I hate evil. What do we call a government with marijuana laws so strict that one man has to tell on another so he can get out in time for his daughter’s fifth birthday?

The girls seem so comfortable with their father—eager to sit on his lap, laugh at his funny faces, gratuitously court his already-granted attention—but this ease feels deceptive. They must associate this place with long drives, nebulous fear, men in uniforms, and their mother’s sadness.

Two frail old white women arrive. One hangs her pink cane on the back of a chair. The cane matches her lipstick. The women are eventually joined by a large black inmate. Charlie watches my face. He smiles, “Not what you were expecting?” He tells me these women are raising the man’s kids. They show him photographs. They buy him a bag of pretzels. Caitlin, the little girl who hates evil, tries to grab the pink cane. “Not a toy!” her mother shouts. The old woman doesn’t appear to notice. She calmly reaches two orange-dusted fingers into a bag of Cheetos, brings another one to her dry painted lips, and watches her tall friend stare at the changed face of his own child.

Charlie and I spend the first few hours talking about his case. He offers a couple theories about Nordlander: probably Nordlander was a kid who got his head flushed down the toilet; maybe he thinks Charlie was the kid who flushed it. I find myself growing restless. Why is that? I feel like I’m in the middle of a story Charlie has already told—which is probably true, but it’s also the story behind his confinement. It’s the story that shapes everything about his life. Of course he’d want to keep telling it.

I feel a pressure to separate my stance from Charlie’s—to make myself author, and him subject—but I also feel it as an act of violence to disagree with him about his own life in any way. I want to talk about his life here. I want to talk about who he has become in this place, what it has summoned from him. But I realize my interest betrays the privilege of my freedom: life in here is novelty to me; for Charlie it’s day-in, day-out reality. For me it’s interesting. For him it’s terrible.

Charlie indulges my curiosity. He tells me he sleeps on a bunk bed in an open room divided into fifty cubicles, like a corporate office, only the partitions are cinder block and no one can leave. He tells me about the black-market currency (stamps) and where the fights usually happen (the TV room and the basketball court). He tells me how life is different across the street, in medium-security, where he’s heard footballs full of coke are tossed over the fence and guards get paid to pick them up. Across the street guys are owned and rented. Sex acts aren’t seen as gay. “Suck a dick here in camp, it’s because you want to,” Charlie explains. “Across the street it’s because you needed the money, or you were forced.” He’s speaking softer so the old women behind us won’t hear.

I can’t figure out if hearing all this brings me closer to Charlie or simply illuminates the gulf between us. Am I learning his world or simply perusing its memorable specifics, shopping like a tourist in the commissary? Sometimes Charlie says, “I’m giving you this,” before offering an anecdote. His prison life is only mine at his bequest. I’m giving him my attention and he’s giving me something else—not the currency of stamps but rather specifics, intimate access—or its texture, at least—granted by way of details.

Charlie is generous with specifics. He tells me he spent two days running 135 miles around the prison’s gravel track back in July. He timed it to coincide with the Badwater Ultramarathon, a race “out there”—through the flat, baked reaches of Death Valley—that Charlie has finished five times. Charlie only stopped running laps for mandatory count, at four o’clock, and then to sleep. These days he organizes a workout group: a guy named Adam, a guy called Butterbean, and the camp’s only Jewish man, Dave, who has an incarcerated wife and a six-month-old baby born in prison. Butterbean has lost fifty pounds since he started training with Charlie, Adam more than a hundred.

But Charlie isn’t popular with everyone. He tells me some of the white guys don’t like that he doesn’t like their racism; and a black guy called him a “white cracker motherfucker” after UNC beat Duke last March. The guy was a Duke fan, and Charlie had been gloating. But Charlie is generally tactful. He knows he has to let the older black guys shush the younger black guys when they’re playing poker too loud; a middle-aged white guy has no place telling them to be quiet. But he also tells me he’s not afraid to get in another guy’s face. You have to be an asshole—just a little bit—if you don’t want to get pushed around.

Not getting pushed around is a relative concept when the government is telling you where your body can and cannot be.

“I’m easy to ignore in here,” says Charlie. He’s learned that weekends are especially difficult—people are busy with their own lives and aren’t in touch as frequently. He feels it most on Fridays. I remember how he described Fridays in his letter: squares of unknown fish, rowdy dominos late at night, no race to look forward to the next day. He can’t do the smallest, simplest things—send a text, for example, or leave a message on someone’s phone, or have a conversation that isn’t punctuated by the constant automated announcement of his incarceration. He lives in another world, and speaking to him always involves speaking across the border between that world and the one we call ours, the one we call outside, the one we call real.

Charlie tells me about his notion of “inner mobility,” something he picked up from Jack London, which involves just that—going somewhere when he’s not allowed to go anywhere. For Charlie, inner mobility means reading books, but it also means following his imagination into other places, other scenarios: “I don’t treat it like fantasy,” he says, “where I always end up naked with the beautiful woman.” Instead it’s something trickier, less like wish fulfillment and more like making himself vulnerable to circumstance—one of the many subtle liberties this place denies: the freedom to be acted upon by many frames, many scenarios, rather than the single abiding context of incarceration. The principle of inner mobility is double-edged, opportunity and consequence: “I am free to nap when I want, go for a run when I want, fall in love, jump from a building, or eat cake till I puke,” he says. “The most important rule of my inner mobility is that I must follow the trail where it leads and sometimes that is not going to end well.” This articulation of desire fascinates me—to follow the trail wherever, not just someplace good. Incarceration doesn’t simply take away the ability to get what you want, it takes away the freedom to screw up—binge on cake or jump from too high or fuck the wrong folks.

Charlie tells me he stopped asking friends to come because it felt too painful to watch them leave. Wish You Were Here is just a Band-Aid over Wish I Was There; Wish You Were Here is never quite enough. When he tells how that moment of departure hurts, we both know we aren’t exempt. No matter how much we talk, or what we talk about—no matter how well Charlie describes prison, or how well I listen—our visit will end. Every moment we spend together gestures toward this horizon of departure—like the perspective point in a painting, everything refers to it. Confessing it does nothing to dissolve it.

Three o’clock is just another hour in the day but it is also the difference between me and Charlie, between our clothes and the dinners we’ll eat that night, between the number of people we’ll touch in the next week, between those liberties the state has deemed appropriate for his body and for mine. Every guy inside has a dream for when he leaves, Charlie says: one guy wants to sell workout videos based on his prison fitness regimen; another guy wants to run an ice-cream boat.

Three o’clock is when one of us goes, the other one stays. Three o’clock is the end of the fantasy that his world was open or that I ever entered it. When the truth is we never occupied the same space. A space isn’t the same for a person who has chosen to be there and a person who hasn’t.

The neglect here is almost unimaginable—and it’s not just neglect from the Beckley staff but from the world itself—the world that has carried on with its daily business while keeping all these men invisibly deposited elsewhere, in a slew of the nation’s most obscure corners. On the outside, you can think about prison for a moment and then you can think about something else. Inside, it’s every moment. It’s impossible to ignore.

The fog count comes at three o’clock—on a perfectly clear day—and some of us exercise our right to disappear and others are reminded that they no longer can. One man exercises his right to run 540 times around a gravel track. What happens when you confine a man whose whole life is motion? I guess that, those laps.

Maybe tonight I’ll dream those endless acres of moonscape beyond the beauty lines. Maybe I’ll meet that stranger again. Maybe he’ll come back to the greasy diner. Maybe I’ll buy him a Coke, or a cookie the size of his face, and he can stand for every man who’s ever had a story and I can stand for everyone who hasn’t listened hard enough. I’m easy to ignore in here. I’ll ask that stranger every single question any person ever asked another person. I’ll ask enough questions to dissolve rhetoric and cinder block partitions; I’ll ask him enough questions to make him visible again, so many questions we’ll have to stay in the dream of that diner forever.

Fog counts come when the sky goes opaque and movement feels possible, when the boundaries between the free and the quarantined are harder to see—never dissolved, only hidden—and so the tallies arrive with greater urgency: those who have done wrong are tallied, those who haven’t are tallied beside them, and all around the perimeter is a border backed by guns—or the threat of extended sentences—and this border runs like a scar across already scarred land. Prison is a wound we keep tucked in those parts of the country that can’t afford to turn it away, who need its jobs or revenue, who must endure the quiet violence of its physical presence—its “Don’t Pick Up Hitchhikers” warning signs, its barbed-wire fences—the same way a place must endure the removal of its mountaintops and the plundering of its seams: because a powerful rhetoric insists that we can only be delivered from our old scars by tolerating new ones.

© Nathan Alexander Ward

© Nathan Alexander Ward

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.