Welcome to Soul City

By Amanda Shapiro

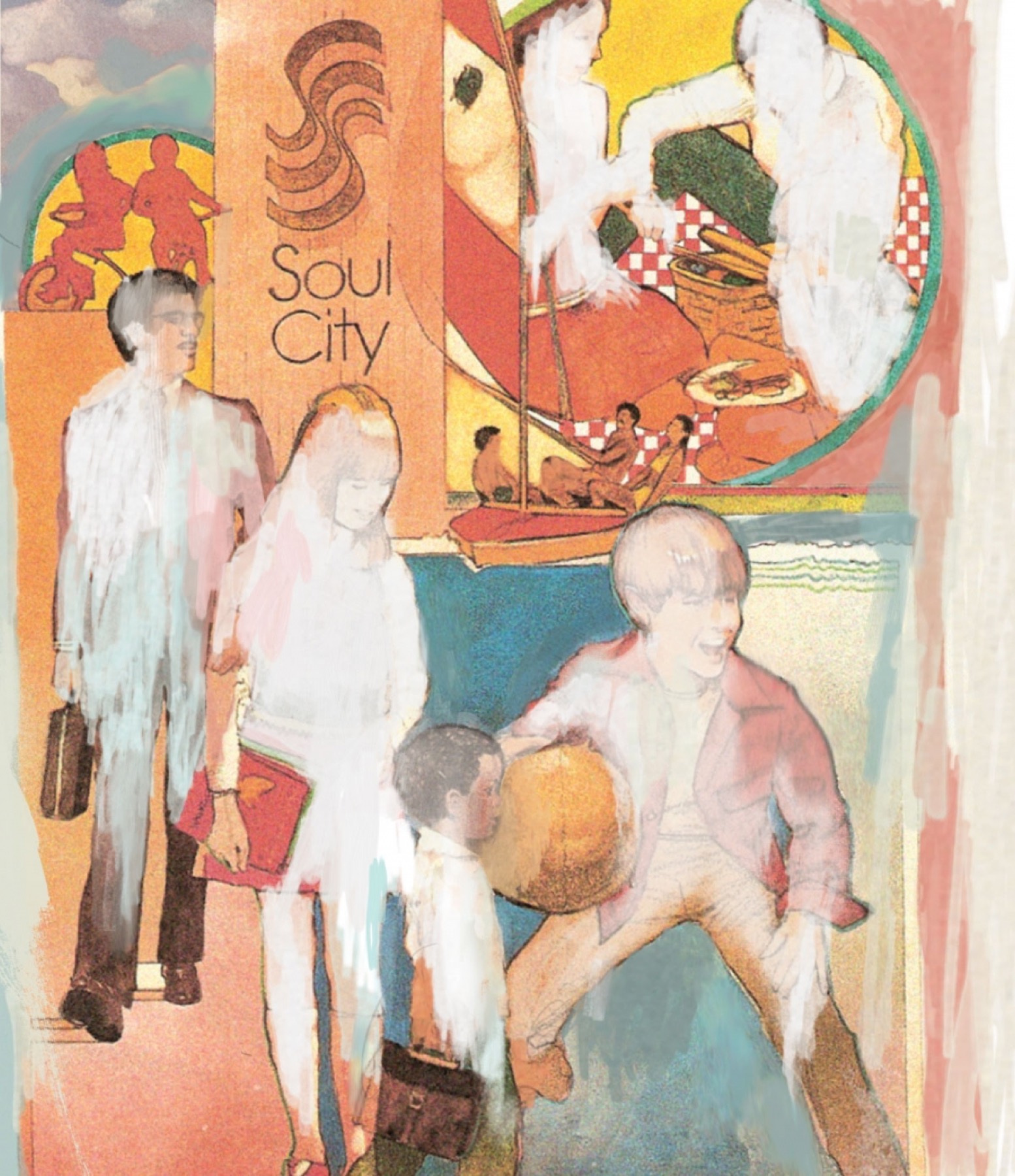

Illustration by Tom Martin, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development advertisement for Soul City, circa 1970

Drive north from Raleigh, North Carolina, a city that stands for all that is positive and prosperous in the New South, and you might feel that you’ve entered another world. Warren County is fifty miles away, past farms and hickory forests veiled with kudzu and preternaturally green. It is one of the most rural counties in the state. Also one of the poorest. The population is a little more than fifty percent African American; more than one in four people here live below the poverty line. Jobs are scarce, healthcare is limited, and schools perform below state levels.

It’s hard to believe that these acres of farms and pastureland might have become Soul City, a Black Power experiment, one man’s quest to build a black-owned community from the ground up. If Soul City had succeeded, the county’s population would have quadrupled, attracting both blacks and whites who’d been fleeing the region for years. Soul City would have been a model for social and economic equality in the South. And it was more than a quixotic dream: the federal government backed it to the tune of $14 million. This was in the 1970s, when so-called New Towns with their own industrial bases were supposed to solve the dual crises of urban overcrowding and suburban sprawl. But like housing projects before them, the government’s New Towns were plagued with contradictions and most were shuttered within a decade. Soul City was one of the failures; industries could not be convinced to take a chance on Warren County. And despite the efforts of many well-intentioned people, Warren County’s economic circumstances have not improved much over the decades. The predicament is shared by rural communities across the South, many of which are struggling to catch up to an era that has already passed them by.

In Warren County people say there are more antique stores per square mile than there are people. It’s an impossible notion but everyone will tell you it’s true. The signs are everywhere—antique shops, antique malls, consignment shops, thrift stores—the same signs that proliferate across the rural South. Antiquing is a hardy business, it seems, a safe zone in a region with something of a fraught relationship with the past.

Before the Civil War, Warren County was a destination. People there were rich. It was the kind of place where Southern aristocrats came to relax. They bathed in the local hot springs and stayed at the Panacea Springs Resort and the Shocco Springs Hotel. The railroad came through in 1837; in 1860, slaves outnumbered whites two to one. Most worked on one of the many cotton and tobacco plantations. Warren County was home to the man who designed the original version of the Confederate flag.

People kept farming in the county after the Civil War—many former slaves became sharecroppers—but the old prosperity never returned. Throughout the twentieth century, the county’s economy was stagnant, and its struggles were hardly unique. Many of the South’s farm economies were collapsing because of declining wages and scarce work. Blacks in particular were leaving in droves for northern cities in search of jobs and a better quality of life. In 1969, the year Floyd B. McKissick announced his plan for Soul City, the average worker in Warren County was bringing home just $136 a month.

Those who knew McKissick describe him as a force of nature, an all-conquering spirit. He was driven, brilliant, and demanding. A lawyer born in Asheville, North Carolina, McKissick led sit-ins across the state and helped organize the Mississippi March Against Fear, the protest at which Stokely Carmichael made “Black Power” a political slogan. He moved to Harlem, where he helmed the Congress of Racial Equality through a radical transformation from peaceful integrationist group to militant black-nationalist organization. In 1968 he stepped down and embarked on what seemed like a dramatic career change. McKissick’s lifelong dream, he claimed, was to build a city, “a place of truth,” “a beacon of light,” “a place where man can develop himself to what he wants to be.”

Beyond the rhetoric, what McKissick envisioned was actually an extension of his Civil Rights work. He believed that protests and legal battles could go only so far toward achieving racial equality. In his 1969 book, Three-Fifths of a Man, McKissick wrote, “Unless the Black Man attains economic independence, any ‘political independence’ will be an illusion.” A new city like the one he imagined would intentionally put economic power in black hands. But McKissick chafed at the suggestion that it would be any sort of enclave. “I’m still an integrationist,” he claimed in 1973. “If it succeeded as an all-black town, it would be defeating my objectives.” He wanted to give blacks a reason to come back to the South, but he also wanted to give everyone in Warren County a reason to stay.

What remains of McKissick’s town is less than ten minutes off I-85, through a ten-road town called Middleburg, clapboard farmhouses, squat brick ranches, double-wide trailers, and field after field, much of it fallow even at the peak of July. A mile or so past the railroad tracks one comes to Soul City. The land is flat, and the lampposts that line the streets seem new and out of place. The boulevard leads to Liberation Road, which leads to Freedom Circle, which leads to a cul-de-sac of small ranches and split-levels, not exactly tree-lined though some patches of foliage do exist. Soul City consists of about eighty buildings, in the middle of which sits a seventeenth-century white farmhouse called the Duke Green House, marked as a historic landmark, a Heritage Center, and a JobLink Career Center. The first time I visited Soul City, I went inside and found Jane Ball-Groom behind a very messy desk. Ball-Groom is a petite African-American woman in her mid-60s. She wears cotton dresses with sneakers and a headband to restrain her short, frizzed hair. She talks fast and with the kind of authority that comes from years of acting as Soul City’s informal spokesperson, defender, and keeper of memories.

“I was the first,” she told me. She moved her family from New York and came to work for Soul City before a single house was built, in 1970. There was no plumbing and no electricity, and everyone lived in white single-wide trailers. When it rained, the roads turned to mud and residents were stranded. Ball-Groom ticked off the names of other families, the original “Soul City people,” as she called them. They were all gone; Ball-Groom was the only one left.

Soul City was obviously a very personal subject for Ball-Groom. She was reticent at first, but the more I exposed my ignorance the more she felt compelled to set me straight, answering my questions with the exasperated tone of someone who has been answering these same questions for decades. I told her Soul City was listed as a ghost town on the Roadside America website. “People come through all the time,” she said. “They don’t expect to find anyone here but here I am. Here we are.”

McKissick’s goals for Soul City were grandiose. He intended to build a new industrial economy on top of 5,000 acres of forest and farmland in under 30 years, not to mention homes, schools, social services, and jobs for the 50,000 people he hoped would move there. The project had few investors at first, but McKissick received what seemed like a transformative gift in 1970 when the federal government promised him $14 million in guaranteed loans. The money came through the Department of Housing and Urban Development, headed by George Romney. At the time, the federal government was still actively engaged in urban planning, hoping that new construction could solve the nation’s social ills. For two decades, HUD had funded urban housing projects such as the notorious Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, which, by the 1960s, had become the symbol of a national failure. Meanwhile, privately funded New Towns like Irvine, California, were showing promising results.

McKissick had a knack for making the shoe fit; it’s no coincidence that his vision aligned with the New Towns trend. He preached the gospel of New Towns, calling them the answer not only to urban blight, but also to the “soul-shattering poverty in our rural areas.” “The roots of the urban crisis are in the migratory pattern of rural people seeking to leave areas of economic and racial oppression,” he said in a 1969 speech. And from a 1973 interview: “The force of the New Town concept is a strong sociopolitical-economic force that deals with every imaginable problem that we have in American society.”

Soul City was probably not “the first free-standing new community in America,” as McKissick claimed, but it was the only HUD project to truly fit the bill of a New Town. The other ventures were all within commuting distance of a city with an established economy. This and the fact that it was the only project with a black developer gave Soul City a lot of national attention but also upped the bar for its success.

It would be easy to draw a portrait of McKissick as a utopian schemer, a con man, as some of his critics did. But everyone who knew him at Soul City is adamant that he was sincere. One of these people is Lewis Myers, an African American in his mid-60s with a close-cropped salt-and-pepper beard. He recruits clients for a renowned architectural firm in Research Triangle Park, and I got the sense he’s very good at his job. He spoke purposefully but casually, and there was a professional warmth to his tone. Myers grew up in small towns in Pennsylvania where he was “aware of the Civil Rights Movement but did not participate in it.” He was in graduate school at Harvard when he met Joycelyn McKissick, Floyd’s oldest daughter. Myers dropped out of Harvard, married Joycelyn, and the two moved to Soul City at her father’s urging. “It was a mission,” he told me. “Like folk that went to Mississippi for the Summer of ’64. It was bigger than any one of us. We lived in trailers on the property, we lived it every day.”

Myers ticked off some of the reasons why Warren County was the perfect location for McKissick’s New Town. The land was just a few miles from two major transportation corridors, I-85 and Highway 1, had a major rail line going through the property, was less than an hour from the airport, and was within 500 miles of two-thirds of the U.S. population at the time. Most important, land and labor were cheap. By the time he finished, I was convinced that he was right. So why didn’t more people agree at the time? Myers didn’t have a ready answer.

McKissick managed to wrangle neighboring counties and the Department of Commerce to create a nine-million-dollar water system that replaced water wells and provided Warren County with two million gallons of water a day. Then he built Soultech I, the first of numerous planned complexes on a 500-acre industrial park. By that point, McKissick was ready to turn to residential housing. He hired Hammer, Greene, and Siler Associates, a business consulting firm that everyone I spoke with referred to as “the folks from California.” The consultant told McKissick that without homes, industries were unlikely to bite. “People were there,” Myers said, “they just weren’t living where the industrial folks could see them.”

According to Myers, HUD had different ideas. Romney wanted industry in place first, a guarantee of at least 300 industrial jobs, before any houses were built. It’s hard to imagine how anyone could expect jobs to appear in Soul City when it was still unpopulated farmland. Then again, it’s just as hard to imagine 50,000 people moving to a city in the country without any prospects for work. “Everyone was talking about us like we were Don Quixote,” said Myers. “They said Soul City was just a boondoggle … nothing there.” The HUD money finally came through in 1974, but by that point political opposition to Soul City was mounting. Senator Jesse Helms called it “the greatest single waste of public money that anyone in North Carolina can remember” and told McKissick privately that he planned to “kill Soul City.” In 1975, Helms called for a federal audit of Soul City’s finances. The audit found nothing amiss but it brought construction at Soul City to a standstill for another 18 months.

The audit didn’t help Soul City’s image with businesses, nor did racist editorials in newspapers across the country, from North Carolina’s News & Observer to the Wall Street Journal. Even the name of the place became a liability. Consultants told McKissick that “Soul City” had “a sort of ‘less-than-solid’ ring to it,” meaning, presumably, that it sounded too black. “Well, they call it the White House and no one complains about that!” replied McKissick. Still, the city lost industrial giants like Honeywell and G.M. because of its name. North Carolina’s governor at the time, Jim Hunt, called the prevalence of blacks in Warren County a “major stumbling block” for industries looking at Soul City.

Eva Clayton is a former five-term Congresswoman from North Carolina; she was the first woman elected to the House of Representatives from the state, and the first black representative from North Carolina since the turn of the twentieth century. Before embarking on her political career, she worked with McKissick at Soul City. Clayton was in charge of creating all the social services the new city would provide: healthcare, education, recreation, religious life. Clayton is in her seventies now. She’d given me directions to her home, “a half hour from Soul City if you know where you’re going.” I was over an hour late. Her house was larger than it looked from the outside: three levels descend in tiers down to the shore of a wide lake. She served us tea in china cups. It was 97 degrees outside. “One sugar or two?” she asked.

Clayton told me that even if the homes had been built and sold and occupied, McKissick still would have had trouble attracting businesses. “We were saying that we could bring industries there, but the truth was we’d have to train people if they were to work there.” Blacks in Warren County had been farming for generations, putting them at a disadvantage even for “unskilled” manufacturing jobs. Clayton also pointed out that fundamental services like healthcare and schools would be top priorities for any prospective employer. These were areas that the Soul City Foundation was focusing on by the mid-1970s. They opened a Head Start and a daycare in 1974 and, soon after, a small health clinic. But with a total staff of around twenty-five and a small budget, Clayton admitted that the foundation’s mission was too ambitious. “We must have looked at the potential that nonprofits could do and thought, do we want to do all that? Of course we want to do all that. Why wouldn’t we want to do that? We want to build the best community we can.”

Why did Soul City ultimately fail? Was it HUD’s fault? Racist politics? The national recession that bottomed out the housing market in 1973? McKissick’s hubris and naïveté? Everyone I spoke with had a different answer. Officially, when HUD foreclosed on Soul City in 1979, it was because they concluded that the project was “not viable and would not become viable.” At that point only thirty-one houses had been built and the industrial park had a single tenant: a duffel bag manufacturer for the U.S. Army.

According to the foreclosure announcement, Soul City had trouble attracting residents because it “lacked commercial and industrial development.” It goes on to note, in perfectly circular logic, that “there is little potential for industrial growth in Soul City” due to the “lack of available workforce.” Most people left Soul City after that, but McKissick stayed in the house he built for his wife and children. He preached at the First Baptist Church of Soul City until his death in 1991. For a while he fought for funding to continue developing his dream, but national attention had shifted away from New Towns and black capitalism, and there were no other sources of support.

Fifty miles from Warren County, the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill Triangle has consistently garnered accolades from the national media. The area frequently appears in top ten lists among the best places to do business, the best cities for young professionals, the country’s biggest “brain magnets,” and its public schools are highly ranked as well. In 2010, when Warren County’s unemployment rate hit 14.8 percent, the Raleigh-Cary area was ranked the number one job market in the nation. The Triangle’s successes are due in large part to the presence of Research Triangle Park, or RTP, which sits at the nexus of the three cities. RTP is the kind of place one can easily end up in accidentally—three highways intersect it—though it’s nearly impossible to escape once you’re inside. Roads wind mazelike through tall woods, interrupted by driveways adorned with corporate signage that seem to extend forever. The signs say Inanovate, Sequenom, and Triumfant. They say Zenalux, Avioq, Cheminova. It’s a country with its own language; it’s the largest planned research park in the world.

Before the 1950s, North Carolina was the second poorest state in the country—most of it looked a lot like Warren County today. RTP was 5,500 acres of worn-out farmland, “nothing but scrub pine and opossums,” as one local described it. But it was surrounded by three established cities and their universities—Duke, North Carolina State, and UNC-Chapel Hill. And its founders were a lot of white men. Still, the venture was shaky for more than a decade and might have flopped without the support of the schools, wealthy textile magnates like Carl Robbins, and Archie Davis, the chairman of Wachovia bank. In 1965, IBM committed to building a massive research facility, and everything fell into place after that. Today RTP epitomizes the rise of the New American South, an economic powerhouse with more than 170 companies that together employ twice the population of Warren County. Because its emphasis has always been on research rather than manufacturing, the Triangle has adapted well throughout a half-century of change. RTP is now promoting itself as an epicenter for enterprises like cleantech, biotech, and advanced biomedical research.

A 2010 report published by the Manpower Development Corporation, a nonprofit research and policy group based in Durham, shows that, of the 20 million jobs added in the South in the last twenty years, nine out of ten have been in metropolitan regions like the Triangle, along with Atlanta, Charlotte, Houston, and Tampa. Those jobs have turned out to be fairly recession-proof too. But what’s worked for the cities and their suburbs has done little for rural areas just miles away.

Dr. John Beck is a North Carolina Humanities Council Road Scholar and professor of Southern history. He calls places like Warren County, which have been left out of the South’s much-touted success, “the Other South.” Beck stressed that widespread poverty is a long-term phenomenon in the South, one that’s deeply embedded in the culture. He sent me a map of U.S. county poverty rates with the top quartile in red. A red streak extends down the Eastern Seaboard from D.C. to southern Georgia where it pools west across the Deep South. “That’s the old plantation belt,” Beck told me. “Once home to millions of slaves, then later to millions of sharecroppers, and now to millions of poor people living in poor counties.” Today, every state south of Virginia has a higher poverty rate than the American average. In this sense, “the Other South” seems to be a misnomer; places like Warren County are the South, while places like RTP are the exceptions to the rule.

Since 2003, an initiative called Triangle North has been working to brand Warren County as an extension of Research Triangle Park. The centerpiece of the initiative was a one-million-dollar grant from the North Carolina General Assembly that Warren County received for a new industrial park. According to the Triangle North website, the park is located in the northern part of the “Research Triangle Region of North Carolina, home to The Research Triangle Park and one of the most economically competitive regions of the world.” Triangle North also touts the county’s “research and development resources” and its “internationally recognized quality of life.” Despite the hype, industries have yet to bite. When I went to the address listed for the park, I found myself at an empty field right across from what used to be Soul City’s health clinic, a beige brick building with a weed-filled parking lot. A small sign by the road advertised, triangle north warren, tier i incentives, development-ready, full utilities, 860 acres expandable to 1,000+.

I drove to the county seat of Warrenton, population 856, to ask Linda Worth about Warren’s economic woes. Worth is the County Manager. We met in her plush-carpeted office inside a squat brick barrack, one of a cluster of county offices at the edge of town. Worth is fifty-five and African American. Like her parents, she’s lived in Warren County her whole life. She was neatly dressed in black, her hair cropped close around her ears and spritzed at the top. She wore little makeup, though her eyebrows were flawless twin arches. Everything in her office was red. There were turtle figurines arranged on the desk and the shelves behind her chair.

“I just like turtles,” she told me. “I’m very much like the turtle. Tenacious. I keep plugging at it. I don’t stop. Just keep on looking forward.” Worth’s emphasis on progress defined our conversations—that and her voice: smooth, almost hypnotic, with the wide-open vowels of a North Carolina drawl. She told me about working in tobacco fields when she was a child, back when the leaves were picked and dried by hand. She was the oldest of eight kids, and helped raise her siblings while her parents worked, her mother in a tobacco factory and a pickle-packing facility, her father as a brick mason. Well-paying jobs were hard to come by in Warren County, but when Worth was nineteen she got a job as a secretary at Soul City. It was 1976. “It was a wonderful place to work,” she said. “We were all treated like we were Soul City family. That’s the way the McKissicks wanted it.”

Worth was one of the last employees to leave Soul City after HUD announced the foreclosure. She now has a bachelor’s degree in business administration and a master’s degree in public administration, and framed on the shelf behind her desk are numerous public service awards. As County Manager, Worth is in many ways engaged in the same struggles as Soul City’s founders were forty years ago. When I asked her what she sees as the most pressing problem in Warren County, she replied, without hesitation, “Jobs.” In the time she has lived in Warren County, she has seen plenty of jobs disappear. The tobacco and the pickle factories where her mother once worked are both closed now. The largest employer today is the school system, followed by the prison and the county government.

A few manufacturing plants remain—“performance fabrics,” cardboard boxes, wooden crates—that rely mostly on an unskilled labor force. But it’s become painfully clear that this kind of manufacturing isn’t the way forward, not for Warren County or for anywhere else in the United States. A survey by the Institute for Supply Management from August showed the manufacturing sector shrinking at its fastest rate in three years. Despite claims by Washington politicians that manufacturing is coming back to U.S. shores, the unskilled jobs that used to come with that sector are not. Most economists agree that the industries that are returning will rely more on advanced technology than manpower, and the jobs they create will require very specialized skills.

Worth acknowledged that such companies just aren’t very likely to set up shop in Warren County. “Our workforce is not the most highly trained,” she said diplomatically. Although some people are moving into the county, they are mostly retirees rather than educated young people looking for work. Warren County remains stubbornly behind the arc of history. In September, when the national unemployment rate fell to 7.9 percent, Warren County’s unemployment rate was above 12 percent. That number isn’t out of the ordinary for rural Southern counties. Minorities are still the hardest hit. The unemployment rate for blacks in Warren County is five times what it is for whites, and blacks who are employed make half what whites do.

I asked Worth about Triangle North and why she thought they’ve had so much trouble selling Warren County as an extension of RTP. Worth said that quality of life is still a major stumbling block; when large businesses open new locations, they bring management teams. And these people bring their families. “If any industry or business were to look at a locale,” Worth said, “they would first look at what type of school system do you have? What kind of recreational outlets do you have? If I brought my family with me, where would we live? We have a lot of substandard housing. We’re trying to bring our test scores up.”

Overall, the school district performs below state standards; nearly half of students in the county don’t read at grade level. College-prep programs have boosted scores and graduation rates in the last few years, but Worth was frustrated to watch those kids leave Warren County for college and know that most of them won’t be returning in four years. “Bring those resources back,” she said. “Don’t take that somewhere else and here we are still sitting here, needing help.”

When I asked if she would sign on to work at Soul City today, Worth said, “I don’t think that the whole establishment of a new town is what we need today.” If someone came in with a lot of money, she’d rather see them open a telephone call center. “Put our people to work,” she kept saying. “We already have a town. We have several towns.” Eva Clayton, who has stayed active in Warren County politics, agreed. “You can have a vision,” she said, “but your priorities, well, you don’t try to do them all at one time.” The same sentiments seem to apply on a national level. The New Town movement has been dead for a long time, replaced by master-planned communities—essentially dumbed-down versions of New Towns that market themselves as “active-living” retirement communities or family-friendly suburbs for high-income professionals.

Yet when I asked Worth if she sees her work as an extension of Soul City, she replied “Absolutely,” and she saw no contradiction in that. What economic development looks like to her is very close to what it looked like to McKissick. In a nutshell: do whatever it takes to attract industries, because industries mean jobs, and jobs mean people won’t leave.

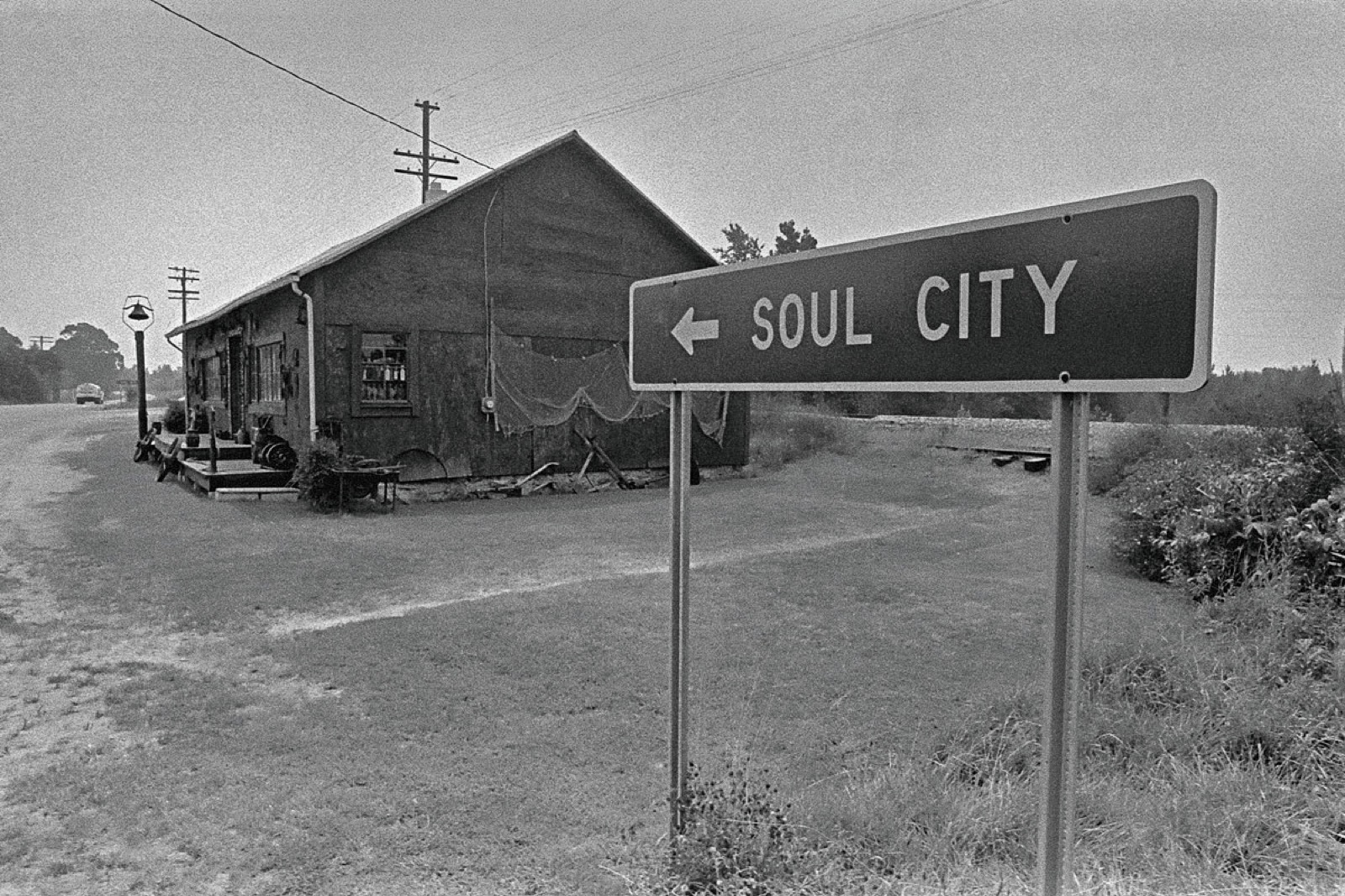

Soul City, North Carolina, 1974 © Greg Allikas, www.graphicgreg.com

Soul City, North Carolina, 1974 © Greg Allikas, www.graphicgreg.com

In a hypothetical list of things that Gabe Cumming is skeptical about, “job creation,” in the traditional sense, is at the top. Cumming is the director of Warren County’s Economic Development Commission, a job he’s held for a little over a year. In that time, he has brought a radical new mindset to Warren County, an economic philosophy that has less to do with industrial parks and more to do with old buildings, pastures, and farmland: in other words, the trappings of Warren County’s former wealth. As opposed to Worth’s talk about forwardness, Cumming’s refrain is more like “what’s old can be new again.” And he hopes that this retrofitted plan can finally bring Warren County into the modern age.

Cumming is white and in his thirties with an earnest face and a tangle of brown curly hair. He speaks passionately if meanderingly about his work in the county, musing his way down rabbit holes and lapsing into silence. His relationship with Warren County is an interesting mix of scholarly distance and fierce personal pride. He has a PhD in ecology and he did a post-doc at Duke’s Nicholas School for the Environment, where he and his wife invented something called the Community Voice Method, which sounds like an acting technique but which Cumming describes as a way to get rural communities to talk about land use and conservation. His wife grew up in Warren County; they used the Community Voice Method there in 2010 and produced a documentary about it. He could be called an activist. He could be called a gentrifier. He’s a smart guy standing in the thorns outside his ivory tower.

We made a plan to go for a drive, and I met him at the Economic Development Commission’s office, which I found in the Armory, the grandest building I’ve seen in the county. Cumming and his assistant, Peggy Richardson, are the only tenants; most of the space is taken up by an events hall with shiny wood floors and a wide stage. The Armory was a 1941 WPA project; in 2010 it completed a grant-funded renovation. Since the renovation, it has become the pride of the county. Weddings, quinceañeras, reunions—everything happens there. “For decades, all of our events went to Henderson,” a town in neighboring Vance County, Richardson said as she showed me around. She told me about the girls who recently came from Henderson to look at the Armory for their prom. “One of them said, ‘We never really thought to look in Warren County for a nice place.’ They were thrilled with this. And I said, well you need to look around. We’re really coming up in the world.”

Cumming was equally rosy. “Warrenton is a tremendously charming town,” he said as we drove down Main Street in his county-issued Ford Edge. “I mean look at it. It’s cute. It’s the kind of town that lots of places wish they were.”

Like a lot of towns that have suffered hard times, Warrenton recalls its better days with such gusto it’s sometimes hard to get a sense of what the place is like now. Streetlamps wear signs welcoming passersby to “Historical Warrenton, founded in 1779.” Plaques in front of Greek Revival houses list dates of construction or family names. Signposts naming notable former residents show up every block or so: Horace Greeley, James Turner, John H. Kerr. I counted four antique shops on Main Street alone.

Cumming pressed on. “We still have these compact downtowns and they’re walkable, they’re attractive, they’re amenable to a mix of businesses being colocated.” He’s right about that: structurally, Warrenton is a New Urbanist’s dream. But it’s also true that any charm on Main Street is due to the paucity of economic growth there in the last half-century. The challenge has been to entice businesses to renovate the aging buildings downtown instead of buying up cheap lots in the strip mall down the road. But Cumming believes that with a few incentives, the charm will sell. What’s old can be new again.

Next we drove to the community of Ridgeway, a short stretch of road alongside the train tracks where the volunteer fire station advertised Frozen Stew for six dollars. We pulled up next to a long hut with open sides—it was a cantaloupe-packing house. The Ridgeway cantaloupe is perhaps the most famous product to come out of Warren County since the Confederate flag. According to the lore, there’s a particular type of soil in Ridgeway that produces a sweeter, denser melon. Cantaloupe production peaked in the ’40s and ’50s, when workers were packing boxes twenty-four hours a day and loading them onto the Raleigh & Gaston freight trains, which delivered them all along the East Coast. Now the packing house is vacant and the tracks are unused. Only one cantaloupe farmer has held on in Ridgeway and he also grows soybeans now.

Cumming sees the Ridgeway cantaloupe as an example of what could boost Warren County’s economy now: a local food product with regional demand. He points out that the Triangle, like just about every metropolis in the country, has an intense interest in local food, and that so far Warren County has been left out of that market. Soybeans are by far the largest crop in terms of acreage, and for good reason. Soybeans receive billions of dollars in federal funding; food crops receive virtually none. Soybeans can be planted and harvested on a large scale with minimal labor and big machines. Food crops need smaller plots and more labor. But Cumming thinks that, with the right infrastructure, switching to fruits and vegetables would add jobs and bring more money into the county. A couple pounds of sweet potatoes sold at the farmer’s market in Raleigh might go for three dollars; an equal amount of soybeans might sell to a buyer in China for under 50 cents.

But here’s a question: Do people in Warren County want to farm, or does Cumming just want people in Warren County to farm? The fact is, most people in Warren County are a few generations removed from farming as a way of life. By Cumming’s count, there are only twenty-five full-time farmers in the county, and they’re farming mostly cash crops like soybeans and tobacco. They are all white. The unemployed population is predominantly black, and they’re coming from assembly lines, not fields.

Cumming insisted that those numbers are deceiving. “There’s a tremendous amount of food production that doesn’t meet the definition of farming by most people’s standards,” he said. Many families have subsistence farms—there are at least 600 “large gardens” in the county—and they sell leftovers from their porches or out the backs of their trucks. Cumming said the racial makeup of that population reflects the demographics of the county as a whole. Linda Worth, for her part, is skeptical. She doesn’t outwardly dismiss Cumming’s plan, but she seems to think it would take a long time to transition to the scale and type of farming that would turn Warren County’s economy around. Employment and capital investment are the two traditional measures of economic development and growing vegetables isn’t a quick path to either.

But quick paths don’t seem to have worked that well around here or in much of the rural South. John Beck points out that developing an industrial base that produces widespread prosperity takes longer than many people—even development experts—realize. In some cases, nearly a hundred years. And Cumming will tell you that his brand of economic development is more stable in the long run.

Cumming has devoted his academic career to studying natural resource management in rural communities, so when he says agriculture is Warren County’s best economic bet, it’s a bit like your dentist telling you that flossing will make you live longer. But Cumming is quick to defend himself against charges that he’s some kind of wonkish, tree-hugging Luddite. Warren County does need industries, he says, just more than the kinds it has traditionally tried to attract. In order to build a viable agricultural economy, you need things like cold storage facilities and distribution centers and processing plants: industries that take your vegetables, your cattle, your timber, and make them worth more. That way, when those products leave the county, more money stays.

We turned down a gravel driveway marked with a wooden sign that says Peck Manufacturing. There was a high fence and a gate with a few no trespassing signs plastered on it and another that says property of warren county. Peck Manufacturing opened in 1910. The textile plant employed thousands of people in Warren County until closing abruptly in 2001. Textile jobs across the South were moving overseas. “The company ripped the equipment out through the wall before they left,” Cumming said. “This was not a departure that left a lot of value behind for the community.” Now it’s an empty warehouse and a series of smaller buildings, some of which are nothing but skeletons surrounded by pieces of drywall and debris. The place looked like it had been bombed.

The Peck Manufacturing property symbolizes the crux of Cumming’s economic vision. As he circled the wreckage, Cumming described what he hoped this place will be: an incubator for “value-added” industries—a specialty furniture maker that uses the county’s timber, a processing plant that uses locally grown cabbage to make coleslaw, a slaughterhouse that buys local meat. He likes the idea of taking a space that was once a burden to the county and turning it into an asset, purposely locating something he calls “new and interesting” in the ruins of the former economy.

Interesting, perhaps, but not so new. The value-added model is exactly what Warren County had for most of its history with its cotton mills and tobacco warehouses, even Linda Worth’s mother’s pickle factory. But the world has changed and those places are gone now, yet Cumming says the model is still a good one. In this sense, his ideas are a lot more traditional than what’s been happening for most of the last hundred years. If Worth is stuck on Version 1.0, Cumming is going back to beta. You’d think it would be easy for him to convince a population with so much nostalgia for the past. When it comes to the economy, however, a different kind of sentimentality holds sway.

“We have managed to progress,” Worth kept telling me. “There are resources out there that we’ve tapped into and brought into the county that have helped us to move forward and not move backwards.”

But Worth’s talk of turtles, and tenacity, and forward momentum represents an equally pernicious attitude toward development. On a national level, this full-steam-ahead philosophy has led to a conception of the rural South as a collection of vacant lots waiting to be filled. A value-added philosophy like Cumming’s doesn’t see them as vacant lots. It sees viable land. “You don’t recruit a farm and then they relocate to Malaysia the next week. It’s the land. The land is here.”

Cumming’s hope is that, if Warren County looks backward, it will finally catch up. But looking to the past is a sensitive proposition in the South. It’s one thing to renovate a historic building. It’s another to suggest returning to an economic system that was built by slave labor and sustained by black sharecroppers and low-wage laborers well into the twentieth century. Not only are the farmers in Warren County white, all the local businesses I visited—some of them places Cumming hopes might start sourcing locally—are white-owned too.

This is the part of Warren County’s history that no one is talking about: McKissick’s most controversial agenda, which was to give blacks a stake in the Southern economy. Black-owned businesses have increased drastically across the country, but they are having trouble staying afloat. As of 2007, black-owned businesses contributed just half a percent to total business revenues. In Warren County, a third of businesses are black-owned; they contribute 4 percent of countywide business revenue. So an industrial recruitment strategy like Worth’s and a value-added model like Cumming’s might both have a shot at creating jobs, but can either change the existing system of economic inequality?

I went to only one antique shop in Warren County. It was in Norlina, the largest town, population 1,117. There were no other customers, just a woman with watchful eyes standing with a man behind the counter. They talked about winter coming on and how they were going to handle the plumbing this year. The store was massive, and I stayed too long. I felt a sense of being lost in time, not just in this store but in all of Warren County. I don’t mean stuck in the past. I mean truly lost, as in confused about what’s old and what’s not, what’s worth saving and what’s better left behind. The Soul City pool was full of rain water. There were blackface dolls in the curio shop. Trucks stacked with timber rolled past the skeletons of barns.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.