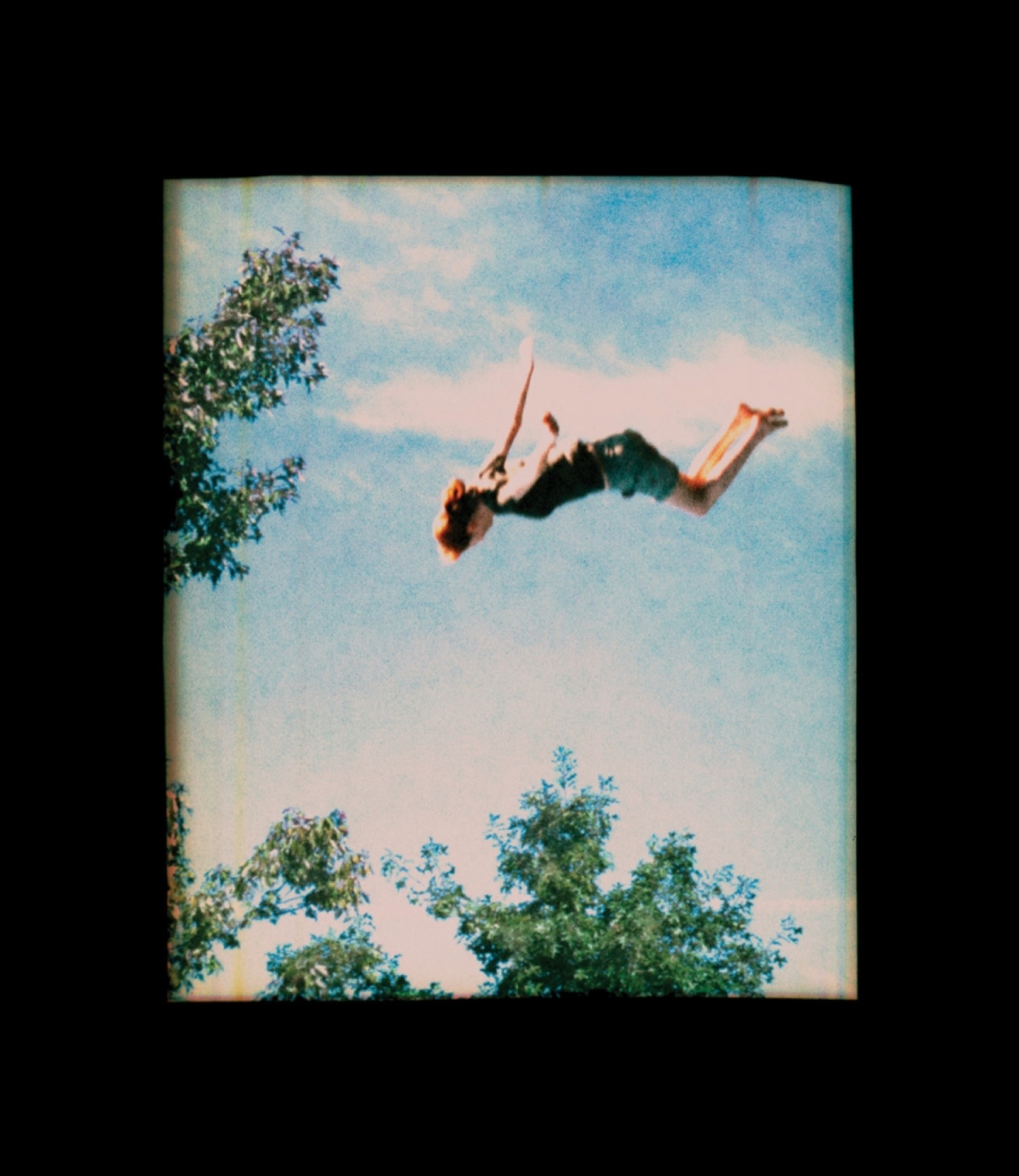

“Falling in Trees 2” (2006) © Elijah Gowin. Courtesy of the Robert Mann Gallery, New York

Crossing the Bridge in Arlington

By Nic Halverson

O

n a frigid, mid-January morning in Arlington, Virginia—more than two months before opening arguments in the landmark same-sex marriage cases before the U.S. Supreme Court—Reverend Jasmine Beach-Ferrara stood in another limbo of sorts, between the Arlington County courthouse and the county jail. As executive director of CSE, the Campaign for Southern Equality, an Asheville, North Carolina–based organization seeking full equality for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, Beach-Ferrara addressed a crowd of a couple hundred people. All were there as part of the WE DO Campaign, CSE’s civil disobedience effort that, for nearly a year and a half, has organized LGBT couples from across the South to apply for marriage licenses in the communities they call home.

“Right now, we are second-class citizens in the South,” said Beach-Ferrara, flanked by interfaith clergy members. “What’s happening today is about us telling our country a story that we hope can open people’s hearts and minds.”

Beginning January 2 in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, the WE DO Campaign’s fourth phase made its way across Alabama, Georgia, Tennessee, the Carolinas, and Virginia—all states where LGBT people not only face strong opposition to their marriage rights, but also lack basic legal protections and resources that many in the North take for granted. Among the crowd in Arlington, wrapped in hats and scarves, were fourteen couples ready to take action.

Washington, D.C., was the first jurisdiction south of the Mason-Dixon line to recognize same-sex marriage, followed only by Maryland this year. The plan, weighted with symbolism, was to begin the march in Virginia, cross the Potomac on the Arlington Memorial Bridge, and conclude below the steps of the Thomas Jefferson Memorial in D.C., where Beach-Ferrara would perform a marriage ceremony.

To expedite the requests and denials, Arlington County’s clerk of the circuit court, Paul Ferguson, met the couples outside, in the no-man’s-land between the courthouse and the jail. After eloquently commending each couple for coming forth, Ferguson asked if any of them were there to apply for a marriage license.

First to step forward was Carol McCrory and Brenda Clark, a couple from Fairview, North Carolina, who have been in a committed relationship for twenty-five years and raised two daughters. “Are you both of the female sex?” asked Ferguson. When they responded in the affirmative, he replied: “I’m sorry, by the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, I am not able to issue you license, but I will gladly hold this on file for you.”

“We know that you’re just doing your job,” McCrory said, her voice quivering.

Second in line was Ivy Hill and Misha Gibson, a newly engaged couple from Piedmont, South Carolina. After being rejected, Hill looked Ferguson in the eye and said: “We had a feeling you might say that this morning.”

One by one, each couple stepped up to get stonewalled. Some swallowed their fate soberly without word, while others pieced together defiant statements through tears.

“As you look around, the people who are here to support you—the clergy, the friends and the family members and the thousands of people across the country sending their support—will be right here with you as we do it,” Beach-Ferrara hollered, rallying the group and kicking off the march. “Thank you for your courage. Thank you for your dignity, your clarity, and your hope that what we do can have an impact far beyond what we see today.”

With that, the tightly bundled congregation headed east toward the Potomac River. The sign-carrying mass wove its way by a construction site, prompting workers to lean on their shovels, then snaked its way through a residential neighborhood where police blocked intersections with squad cars flashing blue lights. It was here that I caught up with Hill and Gibson.

“This was our third time. We applied twice in Greenville,” said Hill. “We ran into a different experience there. There was a couple in line ahead of us who were getting granted their marriage license. The woman was pretty vocal in her opposition of our equality. She misquoted several Bible verses. She was being overly celebratory when they signed their paperwork.” During that encounter, Hill silently held her chin high, stared straight ahead, and issued nothing but a stoic deep breath. Her fiancée broke down in tears.

Hill, a real estate investor who manages her parents’ campground, says history is repeating itself in the South when it comes to the LGBT community’s struggle for equal rights. “You’re going to see something similar to what we saw with the civil rights movement. The South was the last to change,” she said. “We’re a solid decade behind the rest of the country with our mindset here. But it’s coming. It’s just a matter of time.” While Hill calls her fight the civil rights movement of her generation, she’s mindful enough not to overstate things. “We’re not risking our life and the police are on our side,” she said. “It’s definitely a better climate, but there’re some huge similarities.”

Susan Myers and Sheila Milne were legally married in December 2011 in New York but live in Wilson, North Carolina. Together for twenty-six years, the couple have an eleven-year-old daughter, Cameron. Near Arlington National Cemetery, as the march made its final push toward D.C., Myers told me of quitting work for five years to raise her. During that time, she needed surgery, but because she wasn’t covered on Milne’s insurance, the couple had significant medical bills. “We figure, over twenty-six years, we’ve had to pay probably twenty thousand dollars that most people wouldn’t have to pay,” she said. Four days later, while watching the inauguration of President Barack Obama with her parents, Cameron got the idea to write to all nine Supreme Court justices. She sent a heartfelt letter asking them to consider her family when making decisions on Proposition 8, California’s gay marriage ban, and the Defense of Marriage Act, which prevents states from having to recognize out-of-state same-sex unions.

“If you have any concerns about the welfare of kids of gay parents,” she wrote, “I can tell you that I am doing great. I am so loved. Everyone I know tells me I am such a lucky kid. My parents are my life.”

In March, the sixth-grader returned home from soccer practice to find a manila envelope from Justice Sonia Sotomayor, who included an autographed portrait and note. While Sotomayor stressed she couldn’t “comment on matters that might one day come before the Court,” she did tell Cameron that “dreams can come true if you work hard to achieve them.”

“H

old your heads high,” Beach-Ferrara commanded. “We’re about to cross into D.C.” The east end of the Arlington Memorial Bridge is flanked on both sides by golden equestrian sculptures that compose “The Arts of War.” The northern pedestal is “Sacrifice,” while the southern is “Valor.”

As they crossed the Potomac, couples grasped hands. In unison they sang the call and response “We are not/backing down.” One of those voices came from Raymie Wolfe, who sang in an impressive vibrato while walking next to his partner of seven years, Matt Griffin. The couple first applied for a marriage license the week before in Morristown, Tennessee, near their home in White Pine.

Wolfe works as an entertainer at a Christian-owned theme park and says he’s worried he could get fired if word of his sexuality gets out. Tennessee law offers no protection that prevents employers from firing a person because of sexual orientation. “I’m doing this in spite of that,” he said, walking along the Tidal Basin toward the Jefferson Memorial. Though not legally married, Wolfe refers to Griffin as his “husband,” a title he feels is self-evident, despite the law. The term “partner,” he says, sounds too business-like and “boyfriend” sounds too juvenile. The semantics he’s looking for can only be found within the lexicon of marriage. “If we have to fight over that word, we will,” Wolfe said. “When I think about civil unions, I think about drinking at different water fountains, but it’s the same water. It’s the same love.”

Closing in on the Jefferson Memorial, the chorus of the Dixie Cups song “Chapel of Love” rang throughout the procession. On the cement slab below the Memorial steps, in full view of the Washington Monument and the Tidal Basin, organizers had arranged two blocks of eighty chairs, separated only by an aisle. Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 played over a P.A. system as the overcast sky was ripped open by military helicopters likely doing practice runs for the upcoming inauguration.

As friends, family, and supporters took their seats, grooms Mark Maxwell and Tim Young milled about in their distinguished black overcoats, top hats, and cream-colored scarves. Both wore shiny pins on their lapels. Young’s was a gold cane and top hat, while Maxwell’s was a glittering rhinestone sword. “I see this almost as a battle sword for our cause,” Maxwell said. Maxwell and Young have been together for more than twenty years and raised four boys. Though they applied three days earlier in their hometown of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, the couple chose not to do so in Arlington. “It’s emotionally draining to go through that,” Maxwell said. “We just didn’t feel that we wanted to take that in before we crossed over into D.C. We just wanted the positivity.”

Maxwell and Young walked down the aisle together to an operatic rendition of “This Day.” Waiting for them was Beach-Ferrara, who lucidly summoned “the angels of our nation’s history.” Her voice boomed from the speakers. “Looking around, we see in our mind’s eye images of people from our history. And we hear their words—words that have inspired us; deeds which have stirred, which urge us forward in the pursuit of equality and dignity and justice for all,” she said. “We hear the words of Thomas Jefferson, who said, ‘When wrongs are pressed because it is believed they will be borne, resistance becomes morality.’”

During the exchanging of the vows and rings, Young’s emotion bloomed in his red, tear-stained face. Maxwell rubbed his thumb as they held hands. “You have exchanged vows. You have shared rings. And now, by the authority vested in me by the laws of the District of Columbia, it is my great honor to pronounce you legally married,” said Beach-Ferrara to great applause. “You may now kiss your husband and life partner.”

In the jubilant, postnuptial flurry of well-wishers, Maxwell and Young held court on the marble steps of the Jefferson Memorial, posing for photos with megawatt grins. Maxwell ignored the cold and refused to wear gloves—his new ring proudly on display. Young, overwhelmed, found it hard to speak.

Behind the newlyweds, Jefferson’s bold-chested statue peered out through the Ionic columns. Confidently posed to represent the Age of Enlightenment, the nineteen-foot bronze sculpture is surrounded by metamorphic rock from the South. Pink Tennessee marble composes the interior floor of the memorial, while its walls are white Georgia marble. Of the four engraved Jefferson quotations that adorn those walls, one stands out: “I am not an advocate for frequent changes in laws and constitutions, but laws and institutions must go hand in hand with the progress of the human mind. As that becomes more developed, more enlightened, as new discoveries are made, new truths discovered and manners and opinions change, with the change of circumstances, institutions must advance also to keep pace with the times.”

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.