Don't Touch the Dummy

By Jennifer Garza-Cuen

DAY ONE

Donald pulls a dummy head out of his bag at the Cincinnati airport. He’s on his way to the Vent Haven ConVENTion in Hebron, Kentucky, the largest gathering of ventriloquists in the world. The dummy head is a black man’s head. It’s the size of a cantaloupe and attached to a long wooden rod. Donald hoists the dummy above him, lets it feel sunlight, breathe some air, then he lowers it to rest upon his shoulder. The two of them grin in unison. The other ventriloquists, about seven in all, gather around.

“You check that thing?” asks Jimmy V.

“I carried this baby onboard with me. I don’t like them TSA guys digging through my shit.”

The dummy head is spinning. Its eyes open and close.

“Fuck TSA,” one of the ventriloquists says. “I leave notes for those guys: DON’T TOUCH THE DUMMY.”

They talk puppets until the Marriott shuttle arrives and the ventriloquists yank their heavy suitcases onboard. Jimmy V. offers to take the front because he is the smallest. He can’t be taller than five-foot-one but he makes up for it with a booming voice and a thick neck. Mike Palma takes the back and pats his thighs while calling after Jimmy V. “You can sit on my lap if you want.”

The famous Mexican ventriloquist Nacho Estrada takes a seat next to me. He’s slightly hunched in a sad way, and looks at me with a droopy, loveable face and small dark eyes. “I’m the best in the world,” he says.

Jimmy V. hangs his arms over the seatback. “Everybody here going to the convention?”

All the ventriloquists shout yes! Jimmy V. breaks into happy song.

“Wait a minute,” a blonde woman says, rising from her seat, looking at me. “Are you going?”

I tell her I’m writing about the convention.

“Why would you ever want to do that?” Nacho asks.

I tell them I’ve been writing about a similar topic.

“Like what? Epilepsy?”

“Demon possession,” I say.

“That makes sense,” a woman in a purple muumuu says.

“Well, by the time you get out of here,” Jimmy V. says, “you’ll know nothing about ventriloquism.”

“You’re lucky it’s at the Marriott,” Mike says. “It used to be at this shithole called the Drawbridge.”

“We should’ve made a giant bedbug dummy and scared everyone.”

“The Drawbridge,” Nacho whispers. “That’s where the ghost lives.”

Ten minutes later I’m in the Marriott lobby surrounded by hundreds of puppets. They’re peeking from behind the fake motel plants, eating dinner with folded napkins in the River City Grille & Lounge, slipping into elevators. A group of puppets sings in the corner. A fountain bubbles in the lobby’s center, surrounded by fold-out tables, all of them filled with puppets. In a documentary on the Vent Haven ConVENTion called Dumbstruck, the filmmaker emphasizes the challenges faced by the hotel staff: the bartender confusing a forgotten dummy for a drunk man passed out at the bar, the maid caught playing with a dummy in a guest room, and another confessing that she hated it when the puppets arrived because they watched her clean.

In the check-in line, all the ventriloquists are using their dummies to talk their way into better deals. It’s here that I meet Jacki Manna, a children’s entertainer from Florida who got started on puppets when she was on a cruise ship in 1989 with Howie Olson, a ventriloquist famous for his dummy Cowboy Eddie. She was traveling alone and his wife had just died and there was only one table for two, so they sat there together every night and talked about dummies. “Oh, and this man right there,” she says in a whisper. “He’s Mark Wade, executive director.” Mr. Wade walks up and down the hallway like a king, shaking hands with adoring performers. “He’s the Great Man.” She nods toward a mysterious and quiet Japanese man surrounded by women. Takeshi Ikeda, a name I should know. “He’s world famous. This conference is international.” She tells me all the famous names. Jeff Dunham, Jay Johnson, Nina Conti, Dan Horn, Ken Groves, Andrea Fratellini, Lisa Laird. I’ve never heard of any of them.

When Lisa Laird walks past, Jackie waves her over. An Iowa-born schoolteacher, Lisa has glittery eyelids and hair-sprayed bangs. Lisa insists that if I want to know anything about ventriloquism I need to know a thing or two about dead puppets. “The first rule,” she says, “is that you should never let anyone see a dead puppet. A child, especially, should never see a dead puppet. The puppets should have a place to sleep and live. My puppets live in cabinets at school. Even after I put them away, I keep the puppets talking. The puppets never lie down.”

Nacho is monitoring the newbie registration table, wearing sporty sunglasses and a Hawaiian shirt. He walks over, puts his face close to mine, and says, “It’s my job to make you happy.” He points to his name tag: Hospitality Staff. Suddenly his Aquafina bottle speaks. Hello, Jen.

“Do you like scaring people?” I ask. He says that in the elevator just a minute ago, it was just him and this rich Indian guy and so he decided to send his voice down the elevator shaft: Help me! Help me, please! The other man stopped the elevator, searched its corners. When they stopped to pick up passengers, after the door closed, Nacho said, Let me in!

Hurry along, he says, and meet some people. It’s time for “Meet and Greet the Pros” hour, when all the ventriloquists wander the lobby for swooning. I don’t know who’s a pro, so at random I approach Otie Vititoe, a disheveled man holding a manic-looking rabbit puppet. Its soiled ears droop and the whites of its eyes are swirled rainbows.

“I’ve had him for fifteen years now and we enjoy working together,” Otie says. Otie presses his back against the wall and as he talks his eyes pace. On the same Christmas his wife bought him a Kermit doll, Otie bought her a Miss Piggy, and from there, the couple decided it was fate. “Dougie is a fun-loving character. I’m the straight man and he does all the gags. He loves all the little girls in the audience, so he’s always trying to line them up for kisses.”

“Oh,” I say, feeling uncomfortable, stepping away. “That’s—”

Yeah, I like that, Dougie agrees with a high, nasal voice. His body sways. Yeah, I do.

“Do you have anything else to say, Dougie?”

Oh, I’d like to say something. The rabbit scans the room open-mouthed. He rolls his head and screams: Uh, something! Otie distances himself from Dougie in practiced embarrassment. “You’re crazy, Dougie,” he says.

I know. Dougie blinks rainbow eyes. I know.

I leave Dougie for the Japanese ventriloquist Ikeda, who’s standing alone near the coffee machines wearing a navy fleece. He has long, graying hair tied in a ponytail. To explain how ventriloquism differs in Japan, he says, “Very alive. It’s not a figure. Alive, it’s alive. Alive!”

The convention has representatives from twelve countries (though a group of Santa Clauses insist that the North Pole makes it thirteen). Basel Al-Dosery of Kuwait, the convention’s only Arab representative, says that unlike the world’s wealthiest and most famous ventriloquist, fifty-year-old Jeff Dunham, and his controversial puppet Achmed the Dead Terrorist, he’s never done anything to piss off the Arab world. “But now? Who knows! I’m making this character that’s, well, controversial.”

Basel’s performance with a big-cheeked dummy on Arabs Got Talent! in 2011 received six million hits on YouTube. He made it to the semifinals but didn’t win. The eventual winner was an Egyptian, a result he considers unfair because even if all of Kuwait voted he still wouldn’t win.

Basel takes out his iPhone and says, “I’ll show you a photograph of the controversial dummy, but you have to guess. If you can’t guess, you can’t know.”

The dummy is in Basel’s garage in Kuwait, a wooden figure with an inchoate face. “Is he going to be white like that?”

Basel shakes his head no.

I incorrectly guess Saddam Hussein before I correctly guess Muammar Gaddafi.

In October 2011, when the Libyan dictator was dragged into the streets of Misrata and shot, rebels threw his topless, bloody corpse in the back of a van. A few men surrounded him, cupped their hands behind Gaddafi’s skull, gripped his arms, and with fingers on his jaw opened and closed his mouth, making the dictator speak like a dummy.

There’s a dead puppet in the hallway. A finely dressed baboon sitting all alone in a fold-out chair. I feel like I need to tell someone about the baboon but I just sit down next to him and wait for my press pass, which has been held up because the convention officials want to know more about what exactly I’m doing here. They’re suspicious and it’s not hard to guess why. Even in my short time at the ConVENTion, there have been dozens of missed opportunities to take uncompromising photos of puppets, and I can only imagine if you send the wrong person to the puppet convention, a few shots could take down the industry. “We’ve had some misrepresentations,” the public affairs woman explains. “Let me remind you, this is a family affair.” I tell her what I’d been imagining. “Yes. One guy took photos of the puppets doing things they shouldn’t be doing.”

A man named Mark Edson, whom I met on the airport shuttle, walks past and asks if everything is okay. I’d been holding hands with the baboon to see if anyone would notice. “I’ve been given orders not to speak with anyone,” I say. “Or take any photographs.” Mark tells me not to worry. “It’s cool,” he says. “You can talk to my puppet if you want.” Before I can agree he takes off down the hallway. A minute later, he returns gripping an old leather suitcase. Curled inside is an old man puppet named Disco Danny. “It’s a soft figure puppet, like a muppet,” Mark explains. “He doesn’t have any real special features: his mouth moves, and there’s a small rod attached to his palm so that you can twist the arm.”

Disco Danny clears his throat, sucks a breath, wets his hand, and rubs his hair. “What are you doing?” Mark asks. “There’s a lady here.”

I am just trying to look good. Disco Danny nuzzles me. Looking good there, girl.

“I thought you had a girlfriend,” Mark says. I got thirteen girlfriends. “What about that redhead I seen you out with?” Who, Rusty? I don’t see her no more. “She was a homeless girl. Why in the world would you go out with a homeless girl?” It was easier to get her to stay the night.

Mark turns to me and Disco Danny goes slack. “He’s a playboy, an older guy, dates a lot of girls. He’s based on a character I once knew called Disco Danny. Everyone would watch him dance. He kept six girls around him at all times and he’d take one girl, flip her off, and then take another to dance. He never drank. And he was a real person.”

I was a real person! I was really real. “A lot of people will get to know their character by talking to them. I don’t. I already knew the man and this is pretty much what he looked like.” Disco Danny turns to me with a dumb smile. Mark says a lot of ventriloquists base their puppets on real people. “He talks about his relationship with women. Sometimes his health.” Sounds serious. “Jeff Dunham’s got a grumpy old man puppet with his arms crossed. I’ve seen Jeff do six characters at once.”

“I’m a filmmaker too,” Mark adds and he hands me a CD of a movie he made called The Wish. “You can have one of these if you want. I’ll even sign it for you.”

The Wish, as noted on the back cover, takes place in the fictional town of Bergenstein. A street magician named Mike Edwards helps a magical female fairy out of trouble. She grants him a wish to become a famous entertainer, which teleports him into a parallel world where he wakes up only to find he’s married and exists there as an entertainer named Jerry Gator. Mike Edwards nervously becomes Jerry Gator only to be tested by a twist of fate. “Be careful what you wish for,” it warns.

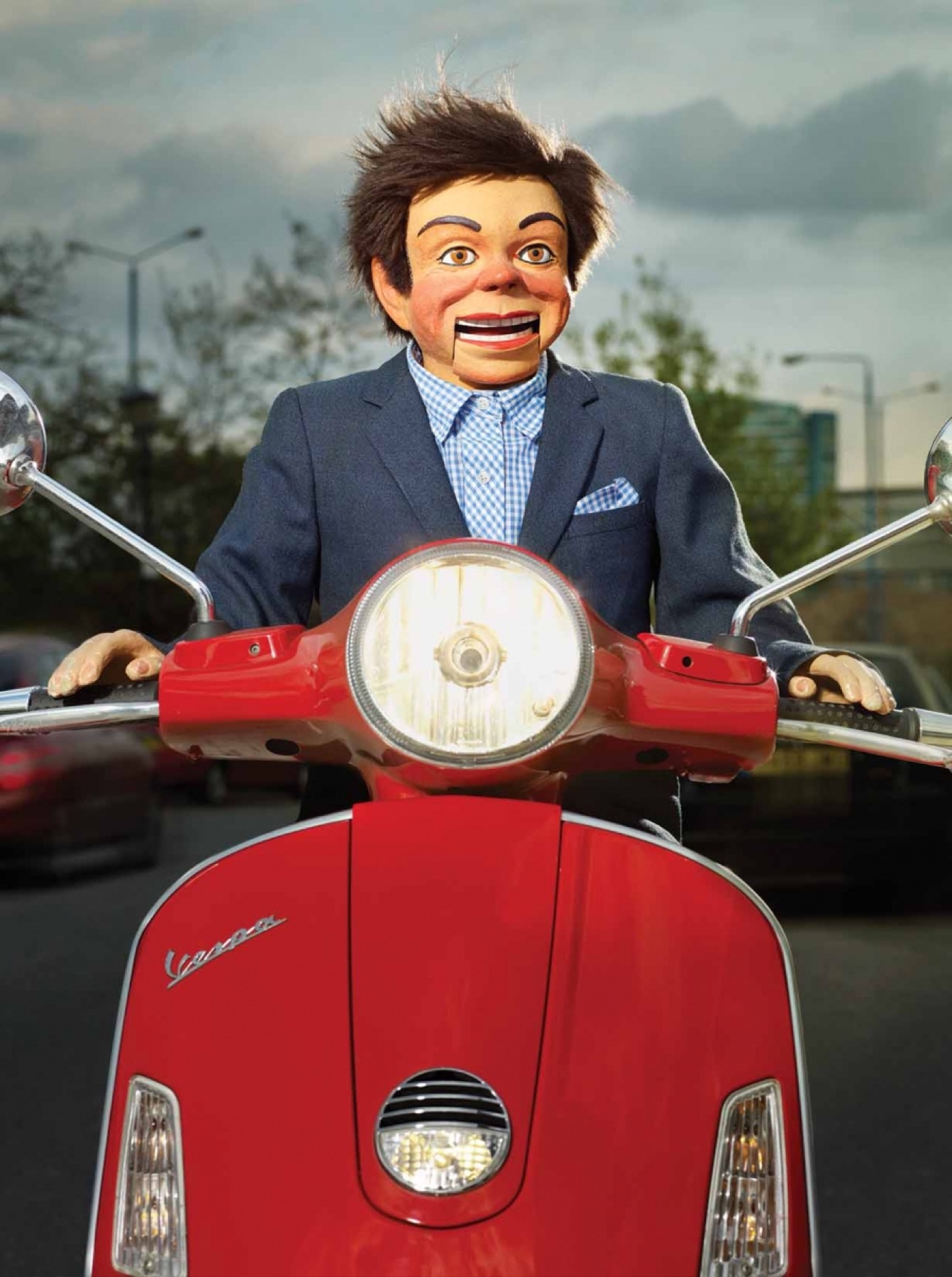

Every night there’s a puppet show in the hotel auditorium, and for the Big Wednesday Night Show, the entertainer Steve Taylor tells us a story about putting puppets in passenger seats to use the carpool lane. “This isn’t CSI Ventriloquist, okay? You have to believe it’s real if the audience is going to believe it’s real. And you know, I never hit a puppet because they’ll call child services.”

A puppet, I learn, must continually move while speaking, and Steve brings Rudy to life, letting each puppet part twitch. “People relate to the big eyes. It’s the Disney effect. You don’t trust people whose eyes you can’t see.” The secret is to move the eyes before the head. Rudy, a handsome boy, is about four feet tall, a giant compared to the more common, infant-sized puppets I’d been seeing coddled in the arms of puppeteers. “The puppet takes care of himself. It’s sort of creepy and weird. Rudy never messes up. I do. A different part of the brain works when you have a puppet. The unconscious goes into the puppet.”

Steve wants to show us examples of how to create different emotions in the puppet but we never get past love, sadness, and laughter. A kid calls out “envy” and Steve takes a pass. I scan the audience, equal parts puppet and human. The puppets, even now, watch the show, always moving, eyes glinting like animals in the dark. An orangutan puppet leans forward, cranks his head, and stares at me across the long row.

My first memory is of my father telling me the orangutan in the yard isn’t real. He was a dirty orangutan and I would see him eating blueberries. My father knew it was a black bear but I remember it only as an ape. Every day he dug around in his eyes, too small for his sockets, and then stared at his wet fingers. He flopped bonelessly about the yard with the mad, lonely look of an abandoned toy. At night, he watched me. In the morning, I searched the windows for ape smudge.

The orangutan puppet won’t stop watching me. The puppets onstage multiply. Around me they jump on laps and their jawless mouths open like snakes’. I sneak out of the show and go upstairs to my room. It’s night, and I can’t sleep because I can still hear the puppets whispering in the hallway. Their shadows flicker beneath the door’s glowing slit.

DAY TWO

Nacho says I can’t go to the puppet photo shoot without a puppet. I tell him I don’t have a puppet. He says that isn’t a problem because he has an extra puppet upstairs in his hotel room that I can borrow. I wait in the hallway outside his door while he digs through his suitcases for the extra puppet. The room is dark. The curtains shut. He’s on his knees, tossing clothes, still wearing sunglasses. It’s an old man puppet, just as Mark warned. Nacho’s own puppet is a Mexican boy named Maclovio. I say, “I hear you’re not supposed to touch other people’s puppets.”

“Doesn’t matter. Touch this one.”

We take the elevator and on every floor, more and more ventriloquists pile inside, warming the air until it’s hard to breathe. A little boy puppet presses against my leg. A giant troll puppet with a nose like a potato keeps cocking its head, bouncing up and down, staring. Mike’s Chinese dummy doesn’t move. Jimmy V. sinks between a toucan and a chimpanzee. Stevo Shüling, the tallest man at the conference, presses against the wall looking calmly ahead, seemingly unaware of the chaos below. Everywhere are those soulless glass eyes.

Something whispers into my ear: Are you afraid?

“Yes,” I tell the puppet who’s been creeping over my shoulder. “Are you a rabbit?”

I am a rabbit.

A man with a dragon puppet wants to know if I’m scared of puppets and when I tell him that I am, he assures me that it’s not an uncommon thing. “Puppet PTSD,” he says.

The term is pupaphobia: fear of puppets. But there’s also automatonophobia, the fear of humanoid figures (ventriloquist dummies, animatronic creatures, wax statues); and pediophobia, the fear of dolls.

In A Brief History of Anxiety ... Yours and Mine, Patricia Pearson says anxiety can be described as fear in search of a cause. Instead of being paralyzed by a sense of worldwide menace, where danger is everywhere, the victim of phobia channels all his dread into one vessel.

For many years as a child I didn’t sleep because of such fears. I developed a heroin-eyed look and a nervous air. Once, on a bright morning when I was ten, I woke up late with dozens of troll dolls covering my body. My brother had put them there. They were on my shelves and on my desk and under my pillow. There was a green-haired troll in my hamster cage. I found one stashed beneath my pillow. The troll closest to my head had a note. Bad dreams, it read. Bad dreams. When I went downstairs for breakfast I found them in cabinets holding notes that said: I will kill you.

I used to watch Tales from the Crypt on weeknights, and one night the crypt monster told a tale called “The Ventriloquist’s Dummy” about the schizophrenic nature of showbiz and how to hack your way to the top. Hoping to improve his craft, Billy Goldman returns to his idol Mr. Ingles, only to discover that he owes his success to a fetal-looking monster attached to his hand that he’d been sticking inside dummies for shows. The monster’s name is Morty and he hates women so much that he has even murdered a few. “There’s just no reasoning with him,” Mr. Ingles says of his crazed puppet. “He’s psychotic.” Billy hacks Morty free of Mr. Ingles’s arm, and after a long, bloody chase involving a baseball bat and insults like “You inbred Cabbage Patch Kid!” Billy captures and tortures the monster until it agrees to help him.

The puppets at the hotel, in all their bestial variations, threaten to become apparitions of these childhood fears, the things that lived in the dark. I suspect that I’ve made a terrible error in coming to the ConVENTion.

The photo shoot is in the Marriott parking lot, and in the damp July heat all 547 ventriloquists huddle like refugees from an episode of Sesame Street: fluffing cotton, patting feathers, smoothing hair. Or maybe the setting of one of those newspaper stories about animals escaped from the zoo, except this time it’s puppets, hundreds of them, loose and wild in Kentucky. After so many hours in the hotel light, I feel a little strange being out there in the sun with them. A photographer, an irritated man on a ladder, uses hand motions to indicate how tightly we all need to squeeze together to fit into the frame. The photo will hang on the wall of the Vent Haven Museum in Fort Mitchell, the world’s only museum devoted to ventriloquism, and the place where most of the dummies of the world end up. The convention occurs in Hebron for that reason—its proximity to the museum, which started as an amateur collection in 1910 under the care of William Shakespeare Berger, a local man who became obsessed with collecting dummies after a visit to New York led him to purchase a dummy named Tommy Baloney.

When the photo shoot ends I hand the old man puppet back to Nacho and I’m alone, dummyless. People take note. A woman named Beth approaches, touches my hair, and wonders, “Are you a ventriloquist?” She tells me how great life would be if I were to become a ventriloquist. What’s your name, lady? her puppet asks. Can I go home with you? Kelly is a homely puppet with crooked teeth and potato-colored skin. Beth smiles and gives Kelly a pat. “I just adopted her.”

I tell the puppet, “I guess you already have a family then.”

I don’t, Kelly snaps.

“You do,” Beth says. “You’re going to stay with me, forever.”

I’m a foster girl! My dad got taken away!

“Her dad got taken away.”

“What happened?” I ask. The police done come to my house and they taken him away. “Yep. She was telling us in there her dad wasn’t doing good things and so her mom and dad got taken away and that’s the way she ended up in foster care.”

Kelly tells me a story about these parents she knew who left their little girls at home so they could go to Chicago and buy drugs. The little girls, they had scabies.

I feel myself reacting the way I would if talking to a person, listening to Kelly’s story, nodding with her, asking her questions.

“The people that are doing meth out here when the foster kids come in, they can’t even come in the foster home with clothes on their back,” Beth says. “The kids suffer, and Kelly is a product of that, unfortunately. So she has been twisted around to more foster homes. More than one, unfortunately. She got taken away from her brother.”

My brother, he is autistic.

“She doesn’t have an easy story,” Beth says, “but there are a lot of kids in America who don’t. I think that’s why she was born this way.”

“That’s a great story you have about your puppet,” I tell Beth.

No, no, no. It’s not great! Kelly seizures. I’ve upset her. The kids pick on me! I can’t go to regular school!

I look at Kelly and then back at Beth. “I’m sorry. I’m a little confused now about what’s real and what’s not.”

“Reality is all the facts I just gave you,” Beth says, tugging Kelly’s braids. “They’re all true. It happened in my neighborhood. It’s sad isn’t it? She deserves a life like any normal kid. A lot of kids are on medication, dealing with different diseases, things like Asperger’s.”

The kids pick on me. They call me garbage can because I eat so much.

“So you’re homeschooled now?”

No! When you’re a foster kid— Kelly rolls her eyes, drifts off.

“Anyway,” Beth says. “I’m sorry, her mood just swung.”

The puppet is quiet in her arms, and Beth calls over her friend Tom Durnin and his blue alien puppet Ozzie. Tom is a tall man with a leathery neck. A fifty-year-old ex-juggler, ex-mime, ex-dancer, ex-clown. He has one fake eye.

According to Tom, Ozzie’s incredibly shy and smarter than any of us here at the ConVENTion.

“Tom has the wisdom of a 900-year-old man,” Beth says, flipping her long blonde hair over her shoulder. They have a flirtation going on, or at least their puppets do, which among the Vents, may or may not be the same thing.

“Ozzie,” Tom says, “liked Kelly’s freckles.”

Kelly had never spoken to a man in her life until Beth met Tom. Their puppets started up a conversation before they did.

“When you connect the freckles,” Tom says, “it completes the picture. It makes it perfect.”

Tom takes Ozzie’s hand and strokes Kelly’s face.

“Now what Ozzie does sometimes,” Tom says, “is tickle people. Okay? Now I’m going to tickle.”

I step back.

“Don’t worry,” Tom says. “I’m just going to do it to her.”

Ozzie has a tuft of hair on his otherwise bald head, small and yellow as a flame. Tom uses the tuft to tickle Beth—her arms and her cheeks and her neck—swabbing the skin as if painting her.

“I almost cried when we met,” Tom says.

Beth laughs, runs a finger through her hair.

“I saw you and Kelly,” he says to me. “I saw your eyes. Puppets draw the eyes. You were very drawn in.”

“Did you hear what she asked?” Beth says. “She asked what was real and what wasn’t.”

Tom looks at me with an open mouth. “The one word in life is creativity. She’s creating a person. Kelly is already real.”

Beth says the first time Kelly admitted she was a foster child was when she talked to Tom. “She became Kelly. It’s not because I sat in my bedroom and thought about it. This is how real they are to me.”

Beth presses her nose into the puppet’s cheek. “I’ve always been able to do it. It was a gift from God.”

Tom slides Ozzie off his arm and tells me to stick my hand inside.

“I want you to experience the puppet,” Tom says. “I want you to experience Ozzie. It’s important.”

His arm is wet and pale from being inside the puppet too long. He makes Ozzie horizontal and pries apart his puppet hole.

I tell him I never thought a puppet would let me experience much of anything.

“Right here,” he says, patting Ozzie gently, the way a parent might burp a baby.

“I don’t want to,” I say.

“Come on.”

I stick my hand in the puppet, an act that makes me feel strangely intimate with Tom. The wetness, the darkness. The insideness.

“Give him life,” Tom breathes.

A small audience gathers. Ozzie stays limp. Slowly, I make the puppet rise, Christlike with his arms spread. My thumb and fingers part to open Ozzie’s mouth. My small pulse wages against his chest.

“Now, listen,” Tom says. “It was written out. It was written out for me to meet Beth and Kelly, and it was written out for us to meet you.”

A light rain starts up and all the puppets look skyward with open mouths as if to drink. The ventriloquists panic and sprint for the front doors. Others hide puppets in coats or stash them in suitcases.

“I just can’t figure out how a bad thing happened to a good person like Kelly. I can’t. Sometimes it’s hard to deal with pain. Now, I’m old enough to be your dad. I don’t have a problem with pain.” Tom slaps his forehead. “When I lost this eye I had a greater vision of life. It’s a really deep thing. I know. Don’t forget this. Pain is something everyone has. All there is in life is moving past pain.” Ozzie sighs. Tom comforts him with a squeeze.

“I was a fireman,” he says. “A teacher. I’m a dad. I just went through a divorce. It’s unfortunate, but the saying I go by is: Birth and death are just two of mankind’s feeble attempts to describe the existence known as life.”

“We get, like, a college education coming together here,” Beth says.

“Now these journalists,” Tom says, “they try to find the most unusual ventriloquist people and they miss a lot about what’s happening out here.” He takes off his baseball cap and leans solemnly forward. “Everyone wants to have a fantasy. When I was on America’s Got Talent I met Kelly Osbourne and she started talking to me very shyly. It’s true. Now I always remember one thing: everyone you meet, they’ve got stuff going on that you can’t even see. You can’t even see it. We aren’t part of the rat race but the human race.”

Tom makes a sweeping motion across the parking lot: the fumbling ventriloquists, the flopping puppets. “These people,” he says, “they’re the most human creations.”

The parking lot has emptied, splattered with feathers, baby shoes, glinting costume jewelry, a pair of little boy’s tighty-whities. A damp puppet smell lingers in the air. I wipe puppet from my arm.

Beth is standing just a few feet away, rocking Kelly. “I’ve always wanted a daughter,” she whispers. “I’ve always wanted a daughter.”

Ancient ventriloquists were thought to be mouthpieces of the gods, mediating the divine for the masses. The word “ventriloquism” derives from the Greek engastrimythos, or “belly-speaker.” The noises in the stomach were once believed to be the moans and cries of the dead, or of gods who’d taken up residence in our bodies. Eurycles, one of the better known engastrimythic diviners of the ancient world, gave prophecies “in the voice of a demon lodged in his breast.” Sophocles located the oracular voice in reference to sternomantis, or “he who speaks from the chest.” Zeus’s priests interpreted oracles from the rustling of leaves. Some prophets spoke through joints, flatulence, vibrations in the ground, or the long horn of an idol.

Ventriloquists point to Pythia, the Greek oracle of Delphi, as their first ancestor. She resided above a deep crack in the mountains of Parnassus, breathing toxic fumes that roiled from the earth, speaking prophecies sent from the god Apollo. “If a God or a tyrant wants to ensure unquestioning obedience,” the voice historian Steven Connor writes in Dumbstruck: A Cultural History of Ventriloquism, “he’d better make sure that he never discloses himself to the sight of his people, but manifests himself and his commands through the ear.” Fides ex auditu, St. Paul says in Romans 10:17—“belief comes from hearing.” Among believers, voice is the way God relates to man. It’s also the means by which God created man. The very word “obedience” derives from the Latin word audire, to hear.

In some accounts of the oracle at Delphi, the priestess is seen not as a receptacle of the gods but only as herself—as the ventriloquist—who in the act of offering to interpret the voice of the gods appropriates the speech for her own purposes.

When the tape recorder became popular after World War II, psychologists Philip Holzman and Clyde Rousey asked volunteers to react to recordings of their own voice. Humans, they discovered, generally find the experience of a sourceless sound uncomfortable and the experience of a sourceless voice intolerable. The scientists called the reaction a “complex confrontation experience” and speculated that the voice made the listeners aware of aspects of him or herself that are mirrored in the voice—“signs of what we might be letting slip outside ourselves,” writes Steven Connor.

In 1780 the Royal Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg hosted a competition to construct a machine that would reproduce the sounds of a human voice. One participant, Kempelen, built a wooden box connected on one side to bellows or bagpipes (the lungs), and on the other side to a rubber funnel (the mouth). A witness to the machine’s voice said, “We looked at each other in silence and consternation and we all had goose-flesh produced by horror the first moments.”

DAY THREE

There’s a group of rogue Santas always sitting in the lobby, eating pizza at the fold-out tables, talking shit about puppets. Three of them travel in a pack and call themselves the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost. A fourth prefers the life of a lone wolf, wearing a kilt, carrying a glittery rabbit puppet, and occasionally smooching with Mrs. Claus in the elevator.

“It’s my son’s second year as Santa,” Father Santa explains. “He’s a good Santa. He and this other guy—they grew up together.” The Holy Ghost—the other guy—with a thin dark beard and hollow cheeks, is the least Santa-like of the Santas.

“You should come to the Santa Convention in Ann Arbor,” says Father Santa. “You’ll love it. It freaked out my wife. It was like stepping inside a Where’s Waldo book. She could never find me.”

Father Santa pulls a comb out of his wallet and starts brushing his beard.

“It’s hard being a Santa today,” he says. “We’ve even gotta pay molestation insurance. When a kid comes up to sit on your lap, you got to have both hands showing, otherwise they accuse you of things.”

“It’s terrible,” his son says.

“Let’s say you’re at the mall or walking down the street and you see another Santa,” I say. “What do you do?”

His glasses slide down the sweat on his nose. “If you see another Santa, you just got to run. You got to get the hell out of that mall!”

The puppet bar opens at 10 P.M. Instead of going to the real bar, the Vents reserved one of the conference rooms by the pool for themselves. There’s a cooler full of Busch Light and three half-eaten pizzas on the table, and everyone just hangs out in the hallway. I join the circle of Internationals. Andrea Fratellini from Italy and the two Germans, Alpar Fendo and Stevo Shüling.

The ventriloquists are smack-talking mimes. They say magicians are the worst. Clowns? Jugglers? So last year.

At a height of almost six-foot-ten Stevo Shüling has to bend in half to talk to me, and accomplishes this task by leaning against the wall and walking his feet forward until he’s almost equal to my height. Gray-haired and aristocratic, Stevo sports thick, square glasses and is encyclopedic in his knowledge of puppets. He wants to know who I’ve talked to so far because he wants to make sure I haven’t talked to the weird guys. “The journalists always come and only talk to the weird guys.”

I tell him about Beth and her puppet Kelly. “Her friend said it was destiny that I’m here.” Stevo pretends to faint. “Why! Why!” I give him the name Takeshi Ikeda and he says, “Oh yeah, such a gangsta. Such a pleasant and suave man.”

Jimmy V. is slamming Busch Light in the corner. Jackie Manna carries a box of New Castles through the room. Andrea Fratellini keeps walking around making light burst from his fingertips. I ask him how he does it. “Jooouurr-nalist,” he says. “Such a journalist question.”

“No, I really want to know.”

Jooourrnalist.

Andrea used to work as a flight attendant out of Sardinia. “An island,” he tells me, “where all the ventriloquists are sneaky and competitive.”

Alpar can’t stop laughing. He’s drawing images of cigarettes in the air, shooting smoke from his cheeks. He’s a demure German with a Ph.D. in economics and an elegant rabbit puppet. He says he’s suspicious of Americans. “Everyone keeps telling me how great I am,” he moans. Alpar performed a magic show dressed as Al Cappuccino, a sketchy Italian in a white suit and aviators, mocking Italian stereotypes. Andrea got onstage dressed in a similar outfit, also making fun of Italians, using his shoe as a cell phone, speaking to his Italian grandfather Zio Tore.

“Go to magic conventions, clown conventions, mime conventions,” Stevo says, “and no one will let you in. I was a clown for two years. I know. Ventriloquists—we’re all family. This is a family reunion. These are my friends. And you know what, it’s a superior art. We have to do all of it.” Stevo insists that he’s the guy to talk to about ventriloquism.

“What’s the reason everyone here loves puppets?”

The ventriloquists, he explains, are timid people, and because they’re too shy to talk, they have to talk through their puppets. “We all have a story to tell. If only there were just one more person.”

The woman who ventriloquizes horses by tickling their gums appears at my side. She’s drunk and slurs hot wine-smelling breath in my ear, says something about how I should date Alpar because he’s a nice boy. The nice boy does a magic trick where a queen of hearts appears scribbled with his number.

“We’re not weirdos,” Stevo says, blinking at the fluorescent hallway lights. Stevo mentions a dummy that came apart and had a heart inside. “I’m not a fan. They’re not real. We don’t think they’re real. Everyone writes about how we all think the puppets are real. Please don’t write about us being weird. We’re not weird.”

He refers to a puppeteer who calls himself Mr. Puppet, an olive-skinned man with dark ringlets fanning a bald head. “Mr. Puppet said: ‘People never make fun of marionettes but people always make fun of ventriloquists.’ But thankfully Jeff Dunham made ventriloquism cool again.” Jeff makes around $22 million a year and is the only ventriloquist to have a show on Comedy Central. “A lot of ventriloquists at the conference are so poor they have to sleep in their cars in the parking lot. It’s all passion.”

Once a journalist tried to get Stevo drunk and admit things about puppets. “I don’t know what he wanted, really,” Stevo says. “Maybe to say we are puppet fuckers.” Stevo told the journalist, “Oh yeah, how about we talk over some Jägermeister?”

I ask what happened.

“Let’s just say us Germans can handle our Jäger.”

Two hands squeeze my shoulders and I jump. It’s Nacho again. “Hey,” he says. “Do you want a freebie?”

“Sure,” I say, opening my hand. He reaches in his pocket and pulls out a small piece of foam shaped like the letter B. “Free B,” he says, “Free-B!” He laughs and walks off, taking the B with him.

“Oh, Nacho,” says the woman who makes horses talk by tickling their gums, “such a romantic.”

“The first image transmitted by television was a ventriloquist’s dummy,” Stevo says, ignoring the others, contemplating irony. The magic of hearing a dummy speak was ruined in part by the superior ventriloqual act of movies and TV, by the recorded voice. “No recordings meant it must be a spirit, something unearthly speaking.”

The most famous American ventriloquist, Edgar Bergen, spent his time speaking to his dummy Charlie McCarthy on the radio. Even in the darkness of the radio the audience could perceive Bergen stepping outside himself, two antithetical personalities engaging in rapid-fire exchange. The following passage, found in a memoir by Bergen’s daughter Candice, comes from a 1939 edition of the New York Times:

Psychologists say that Charlie differs from other dummies because he has definite spiritual qualities. His throaty, almost lecherous chuckle is a haunting thing; his whole attitude of Weltschmerz is astonishingly real. He says things that a human actor would never dare to say in public and gets away with it. But Bergen could not function as an artist alone—he needed his dummy. “Charlie is famous,” Bergen said, “and I am the forgotten man.”

Voice, the philosopher Mladen Dolar believes, is characteristic of that which has a soul. “They are incorporeal bodies,” he writes of puppets, “languages deprived of sense, generic infinities, unconditioned supplements. They become and they are suspended, like the poet’s conscious, between nothing and the pure event.”

“It used to be,” Stevo says, “that if you spoke, that meant you were alive.”

Mark, the puppeteer of Disco Danny, has been lingering nearby. He asks if I’ll do him a favor. I tell him that it depends on the favor. He says it’s for a promotional video for a new magic trick. I follow him down the hallway where there’s a video camera propped on a tripod.

“I want you to be part of this,” he says. “So we’re going to pretend to have just met each other, just go along with it. I’m going to show you a new trick. Then there’s this guy that wants to watch the video and see people’s reactions.”

The camera rolls. “Hey, how’s it going? How’s the conference?”

“Insane,” I say.

“So anyway, I have this little man in my hands. I know you don’t believe me, but here he is.” Mark bunches his right hand into a fist and sets it atop the palm of his left hand. “Now,” he demands, “take that quarter and put it on my hand.” I put the quarter on his hand and he whispers to the dark hole: Hey will you grab this quarter?

A black hand emerges, thick as a garter snake, and snatches the quarter.

“Whoa,” I say.

“That’s all? Whoa? Listen, almost everyone freaks out when they see this little man. There was a woman at the theater,” he explains, “a big black woman, and when she saw the hand she threw her popcorn into the air, screaming. I warned her: Never look into this guy’s eyes because if he sees you he will curse you.”

Mark sways and points his finger at me. “You might see this guy at night. There will be two little red eyes just staring back at you.”

DAY FOUR

In the dealer’s room, a pile of brightly colored orangutan puppets called moffits are for sale. A man digging among them raises his hands in the air and says: “What’s wrong with this country?”

He leans back when he speaks. He has a belly big enough to tip him over. In God I Trust, his shirt says. A twitchy white mustache in the shape of a horseshoe frames pink full lips. He introduces himself as Emmitt Grant, a Baptist ventriloquist from Alabama.

I nod but before I can say anything he gestures in the manner of a preacher requesting silence. “Let me tell you a story. You got time for this? I hate to be on my soapbox.”

Emmitt says that before retiring to become a ventriloquist, he worked for twenty-six years in penitentiaries across the South to support his three little girls. “I’m just like the Apostle Paul. I’ll do whatever you need me to do.” He tells me of his years working at an honor farm in Kilby, and a maximum security prison in Springville, and how he had led many men to God.

Once he asked God to take away his urge for tobacco, and when the prayers were let loose, Emmitt felt a burning sensation run from his lungs to his feet and the cravings were gone.

“I haven’t touched tobacco in thirty-seven years. I’m telling you, God is good.”

The first man he led to Christ was in Kilby. “I told this man, ‘I’m gonna go talk to the chaplain and I’m gonna get you something.’ So I said, ‘Hey, Chaplain, I need a Bible, something to write with.’ Chaplain said, ‘He can’t have no pencil.’ Well, I said, ‘Can he have a crayon?’ ‘All right then, get the man a crayon.’”

Emmitt has helped other men get saved from Hell. He brought inmates to the cold waters of a cow trough to baptize them on moonlit nights; let them slip out of bed in the morning’s early hours to kneel in prayer on cement floors; taught them to read pronouncing Bible words. Good, he said. Good. Sin, he said. Sin.

His favorite story was about a man named Double Ugly whom he met at a prison in Murfreesboro, Tennessee.

“He was double because when the police got him they hit him with a nightstick and his eyeball fell out. Then he had this big scar running down his face. Like this, you know?” Emmitt uses his finger like a knife to fake-slice from one ear to the next. “Anyway. They had to sew Double Ugly’s eye shut.”

At Sunday Bible study, Double Ugly got assigned to cleanup. “I was sitting there and I was looking at Double Ugly and God put words right here in my heart.” Emmitt takes a finger to his rib cage. “God said: Speak to Double Ugly. Every day for five days I’d be sitting there in Bible study and I’d feel this in my heart. God wanted me to bring Double Ugly to Christ.”

He raises his hands in the air between us, flapping them around like fish.

“Next time I went to Bible study I heard the same thing: Speak to Double Ugly.” Every day he heard God’s voice but he couldn’t bring himself to speak. “Then one day I sent him in for lunch cleanup, and the next morning when I did my little Bible reading, I didn’t feel that urge to speak. God didn’t talk to me that day.”

Emmitt recalls the morning of Double Ugly’s death. He was standing watch in the gun tower, peering through its small windows, when he saw the stretcher emerge from the infirmary. He dialed the nurse. You didn’t hear? she said. Double Ugly hung himself.

“Right then, right when I heard those words, right when I heard he was dead, that’s when I heard the howls of Double Ugly.”

Emmitt takes a moment to gather himself, rubbing his shoe on the ground.

“Double Ugly didn’t say: Oh, why didn’t you tell me?” Emmitt shook his head. “He screamed. He screamed loud as he could—clear—as if I were talking to him right now: Why? Why? Why didn’t you tell me? Why didn’t you tell me?”

Emmitt closes his eyes. “Double Ugly’s in Hell now because I didn’t tell him about God.”

“Do you ever see Double Ugly?”

“I don’t believe in ghosts. I know where he’s at. He’s right down here.” Emmitt looks at the carpet and points. “When you’re gone, you’re gone. You don’t come back.”

He reaches for me. “You ever get God to talk to you? It’s okay. You can tell me. I’m a man of God,” he says, and just as I’m about to open my mouth, his stomach releases a slow deep gurgle as if in response.

“That’s right,” he says. “You’ll know.”

DAY FIVE

Before the final show begins, they make us stand up and say the Pledge of Allegiance. They make us thank the veterans, and the wives of veterans, and then they make everyone stand up who married their first love. They hand out tiny American flags so we can race them down the rows.

I catch Stevo’s glare in the audience. He’s there in the back corner, glasses bright with light, shaking his head at me. I turn away and then back. Now he’s standing next to me. “I am this close to losing it,” Stevo says. He’s German, and all this American patriotism has him pissed off. “This has never happened before!”

British ventriloquist Nina Conti gets onstage and performs with a depressed monkey puppet nicknamed Monk who grows tired of being inhabited by Conti’s mind and requests that instead, he inhabit hers. Is this my tragic life? Monk asks. I don’t even know what it’s like to dream? And yet you think I’m real? He attempts to hypnotize Conti, but this only knocks both of them unconscious. Rising from their stupor, Monk tries again. You know, he says, you laugh at your own jokes. Nina responds, “Don’t deconstruct me.”

Maintain the part of your brain where I reside. It’s the size of a tangerine.

“Who’s this?”

It’s me, schizophrenic loser.

“Where are you now?”

I’m in your mind.

“I feel exposed.”

Are you ready?

Nina’s hands rise.

Oh, at last I am in the woman!

There are no puppets in the hallway when I leave the ventriloquist convention at 4 A.M. the next morning. I make efforts to be silent, not to wake the puppets, and I tip-toe down the hallway, past the groaning Coke machines, and into the elevator where I stretch my arms wide in the puppetless space, breathing slow and happy.

I hit the button for lobby. A shadow rises up the hallway’s wall. It’s Mr. Puppet. He’s trotting straight for me, pushing a rolling rack dangling with dead puppets. They’re all covered in sheets.

Mr. Puppet has big purple bags under his eyes. “Wait,” he says, “please.”

My hand hesitates over the button because I don’t really want him to get on. He’s in such a hurry that the rack tips, sending the skeleton puppet Bag of Bones loose from his sheet, arms raised, mouth wide and dark, like the apparition of death being released from his cloak. Mr. Puppet screams and the cold limbs of Bag of Bones embrace his head.

It takes a while for Mr. Puppet to untangle himself, making the quick unsure movements of someone cleaning himself of cobwebs before he rolls the rack into the elevator. We descend.

The ventriloquist Dennis Alwood believes that every professional ventriloquist has suffered from what psychologists call “spontaneous schizophrenia.” The brain of a ventriloquist, in other words, is working for essentially two people—the ventriloquist and the dummy—and every once in a while the dummy will say something unscripted and the ventriloquist will be forced to react to it. It’s in this way that the dummy becomes real. A creation. In a sense, a birth.

In the womb we’re haunted by disembodied voices. As early as six weeks after conception, the fetus responds to external sound, intermittently soothed and agitated.

Voice may be the way we bring the inanimate to life, but it’s also the way we animate ourselves. If the ventriloquists would agree about one thing, it’s that loneliness has brought them to their puppets, a need to bridge their own lives with the lives of another. The puppet is a vehicle for their voice, allowing them to be brave in a world where bravery comes in the smallest steps, sometimes speaking, sometimes letting another human being know: I’m here. I’m part of the world too. The way that crying, our earliest use of voice, is the voice we use to relieve suffering.

Mr. Puppet stuffs his car full of his marionettes. Bag of Bones takes the front. The car rattles off and the tiny silhouettes shake and crowd the windows like a family. I’m left in the dark parking lot, the eerie quiet, watching the distant flickering lights of planes, and I feel seized with a small panic. I don’t want to leave. At least they’ve figured out a way to never be alone.