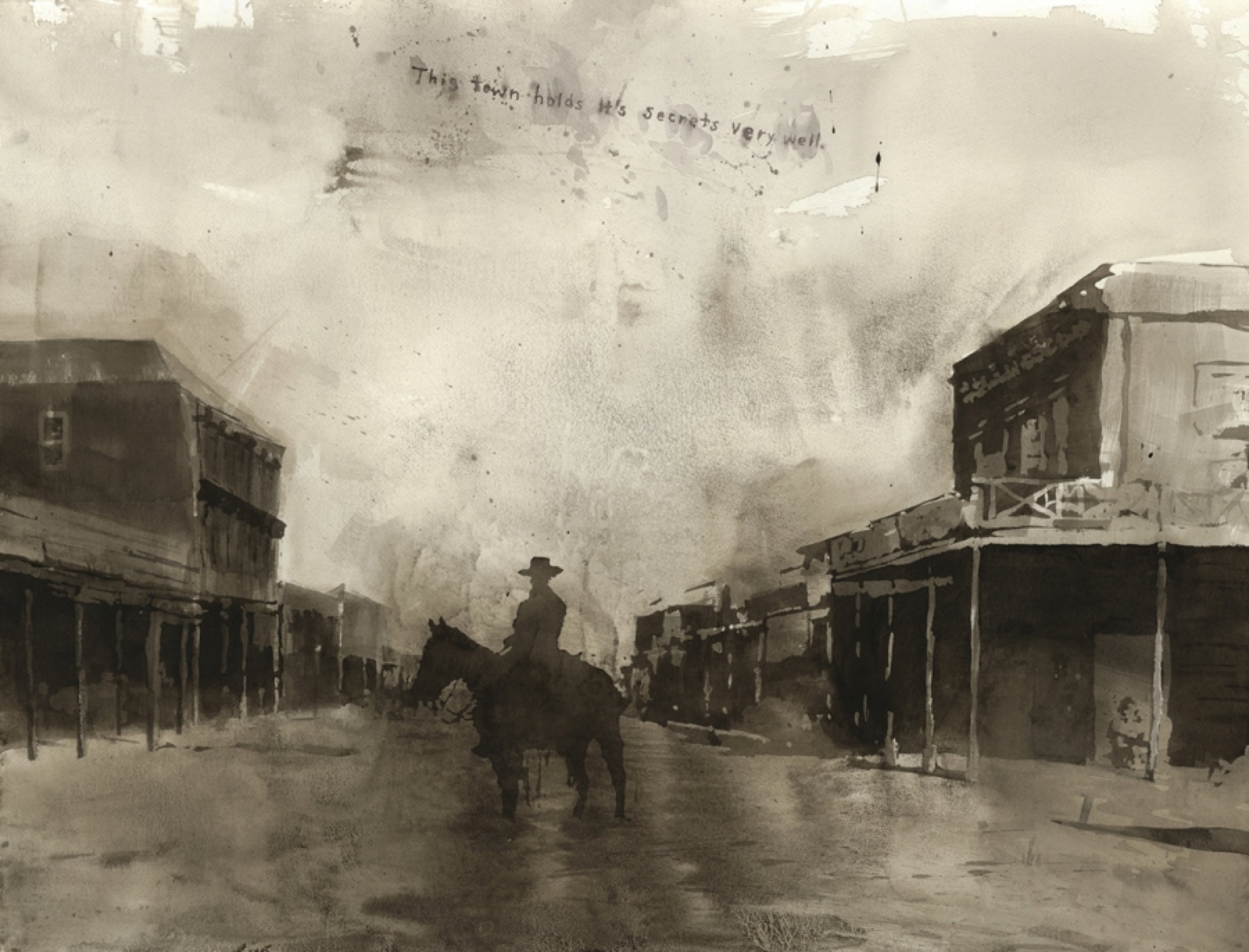

"This Town Holds It's Secrets Very Well" (2011) by David Rathman

Dude Ranch

By Rozalia Jovanovic

“I’m going to ask her to marry me,” said Nic, a young man crouched down on his haunches, a bottle of black spray paint in his hand. He was in the middle of graffitiing his marriage proposal on the hood of a rusted out 1952 Cadillac, stopping every few moments to squint at his handiwork. He had gotten as far as FRANCES WILL Y when his letters began to drip.

Since daybreak, I had been wandering around Cadillac Ranch, an enormous outdoor sculpture made from ten classic Cadillacs planted hood-first in the middle of a wheat field in Amarillo, Texas, abutted by a cluster of RV parks and motels. Erected in 1974 by the art collective known as Ant Farm, the “Stonehenge of the Panhandle” has become one of the most beloved attractions along Route 66. Part of the Ranch’s appeal comes from its conspicuous absence of velvet ropes, viewing hours, and annoying wall texts. Anyone can hang out at the Ranch day or night, and anyone can decorate the cars with little artistic flourishes of her own. After nearly four decades at the mercy of hands-on visitor enthusiasm and punishing Panhandle weather, the Cadillacs are starting to look a bit defeated. They’re in the slow process of caving in on themselves, encrusted with layers of gelatinous paint. But such decay did nothing to hinder Nic’s marriage proposal. A diamond ring was proffered, Frances accepted, and the happy couple walked back to their car. Within minutes a new batch of visitors trickled in: a French woman cavorted between the cars while her boyfriend filmed her; two men clambered on top of another car; five children howled in the distance.

Thirty miles north, buzzards glided over the other iconic artwork of the Texas Panhandle: Robert Smithson’s Amarillo Ramp. Completed in 1973, theRamp is widely held to be a masterpiece and a key specimen of the “earthworks” movement: a 150-foot curving embankment of packed red sandstone shale, rising on a gentle slope toward the horizon. It is also the last work Smithson ever conceived. He died in a plane crash while taking aerial photographs of the Ramp’s tentative outline.

In the forty years since his death Smithson’s reputation has only grown. A massive career retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles in 2004 confirmed his place as one of the most compelling artists of his generation. But on the brisk morning when I visited the Amarillo Ramp in early 2013, no one was proposing marriage. There was no adult jungle gym activity, no impromptu spray-painting or filming of any kind. There was no frolicking. In fact, aside from me and the two guides who drove me out in their Chevy Suburban, the Ramp was deserted. The only signs of life were the gnarled mesquite trees and prickly pear cacti that pushed through the ground like weeds.

These two emblems of vastly different artistic moods of the 1970s—the austere, cerebral Amarillo Ramp and the funky, populist Cadillac Ranch—have one thing in common: Stanley Marsh 3, the scion of an oil and gas family that has owned much of the land in and around Amarillo for generations. Marsh is a towering man who speaks in a whiny twang and is fond of loud shirts and fun hats. He has always been a willfully eccentric and divisive figure, and never more so than in the last year. A debilitating series of strokes and a rash of legal trouble have found Marsh, at age 75, living in semi-seclusion at Toad Hall, his 300-acre Xanadu, surrounded by nutty art installations and a herd of Shetland ponies, wearing a court-ordered GPS ankle bracelet.

Stanley Marsh came of age in the 1950s, when this Bible Belt ranching community was under the cultural sway of the Jim Crow South. As a young man Marsh outfitted himself in overalls and cowboy boots and peppered his speech with disdain for outsiders. In his twenties Marsh left Amarillo to study economic history at Wharton. He returned a few years later, when his father died, to take over the family enterprise, which had grown to include cattle, banking, and, under his watch, a local television station that he turned into one of the highest rated in Amarillo.

Marsh was an effective businessman, but he also gained notoriety as a prankster. He conducted high-powered meetings with a lion cub curled at his legs, he rejected the fancy Roman numeral “III” after his name in favor of a modest and kooky “3,” and he once caused a stir at a high-society wedding by bringing along an Italian dwarf dressed as Aunt Jemima. He showed up at the bribery trial of John Connally wearing a polka-dot shirt and purple chaps, carrying a pail of cow dung. Life was turning into a bit of a game for Marsh: he enjoyed his inherited wealth and local power, but not as much as he enjoyed poking fun at the conservative social world he had been born into.

A 1970 visit to New York proved to be life-changing. Marsh strolled into the Museum of Modern Art, which was exhibiting new work by the Pop artist Claes Oldenburg: spongy-soft, larger-than-life sculptures of hamburgers and slices of cake. And here he found a kindred spirit; the imp in Marsh took to Oldenburg’s playful attitude and was startled to learn that high art didn’t always have to take itself seriously. Upon his return to Amarillo, Marsh began to commission works by some of the art world’s anointed luminaries, inviting John Chamberlain, Ant Farm, and Robert Smithson (among others) to informal residencies in Amarillo, urging them to use his vast and windswept real estate holdings as a blank canvas. With back-to-back commissions of the Amarillo Ramp (1973) and Cadillac Ranch (1974), Marsh kicked off a decades-long pursuit of turning Amarillo into the capital of whimsical art in the Panhandle, subsidizing works all over town—some of them visionary and original, others derivative or half-baked, but all bearing his trademark irreverence.

Stanley Marsh has always had a soft spot for outcasts and wild creatures. A visit with Andy Warhol at the Factory revealed to Marsh how potent and inspiring a mere gathering of people—artists, intellectuals, and drifters—could be. Why not import that model to Amarillo? The 1980s and 1990s saw Marsh’s artistic sensibility turning more from sculpture and earthworks to his own idiosyncratic kind of performance art—or at least the art of social interaction. It started with a group of strangers invited to lunch. Marsh would have them up to his office in Chase Tower (the tallest building in Amarillo) for his “picnics,” and sometimes step out midway leaving his guests to wonder why they had been invited in the first place. Always on the lookout for ways to fit in engaging interactions, he once hired a Marxist chauffeur to debate capitalism with him on the way to work.

Marsh’s need for perpetual creative stimulation and mischief ultimately found its perfect form in the creation of the Dynamite Museum—an informal collective of men in their teens and twenties, mostly aspiring musicians and artists, or just kids who were a little uncouth. Even better if they were waifish, sensitive, and aloof. These foundlings with Mohawks, tattoos, and piercings culled from the local skater/punk scene were Marsh’s hired hands, the young men who did manual labor on his ranch: mixing cement, buying groceries, feeding the menagerie of exotic animals that Marsh kept as pets. Most of the members of the Dynamite Museum started on “sign crew” (making enigmatic street signs offering gnomic advice and nostrums along the lines of THE ROAD DOES NOT END, THE WORLD IS MY APPLE, or LOVER COME BACK), and if it worked out, they would move up to “ranch hand” or “office work,” take on more responsibility, and might even one day, years later, be trusted enough to take visitors on tours of the Amarillo Ramp. They had to be willing to work hard and be positive about the work. But above all, they had to be weird and stubborn.

“It’s supposed to be like a Lost Boys kind of thing,” said Megan Micole, the only woman who was ever hired into the group. “Like Neverland. So girls didn’t really belong there.”

Being one of Stanley’s Boys, as they came to be known around town, was about more than just mixing cement and feeding peacocks. There was a duty to be entertaining, to make up crazy stories if necessary, and to generally contribute to the surreal atmosphere Marsh was cultivating. An average workday might be spent cutting mesquite at the Ramp, but it could just as easily be spent “buying up all the lobsters in town,” painting a car entirely with Wite-Out, or driving around town shouting gibberish through a bullhorn. Though he could afford original artworks, Marsh had his workers paint copies of modernist masterpieces by Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock for his ranch home and office. When the day’s work was done, Marsh and his boys would retire to the man-made lake on his property for a bit of nude swimming at sundown.

For many of the kids who came from poverty or broken homes, the Dynamite Museum became a surrogate family. Christopher Owens (formerly of the rock band Girls), who followed his sister to Amarillo after escaping the Children of God, wound up mowing Marsh’s lawn. He’s one of the group’s success stories. But some of the lyrics to his catchy tunes—“I remember learning how to make a quick hundred bucks, sleeping in the back of a pickup truck”—give shape to dark suspicions about Stanley’s Boys that had been bubbling up in whispered conversation for years.

In October, Marsh was sued by several former employees who claimed that he had solicited sexual favors from them in exchange for cash and fancy gifts—like a BMW, in one case—when they were minors. During the 1990s, Marsh was accused of similar activity and was embroiled in six civil lawsuits (one of which arose after he allegedly locked a boy in a chicken coop), but he remained impervious to criminal prosecution. The reaction this time has been different. Local residents have called for the removal of Cadillac Ranch, and in April Marsh was indicted on charges relating to sexual activities with minors.

On my recent visit to Amarillo, on the first day of spring break, I was eating vegan chili at 806, a coffee shop in the Route 66 district with cushy green vintage chairs and gauzy blue curtains that keep the interior in a perpetual twilight. Later that night, bands passing through on their way to South by Southwest would push the chairs to one side of the room and hold an impromptu performance. But that afternoon, the guy behind the counter was happily surprised to see a young man in skinny jeans and duck fluff blond hair—someone who had the vibe of an artsy Amarillo lifer—standing behind me in line. The barista summoned his friend closer to the counter, made him an espresso, and asked what he had been up to recently. He said he’d been playing some “professional chess,” whatever that means. “It’s only two days a week, and I’d rather work five,” he said. “You know how it is, working for Marsh.”

It’s difficult to know what’s true or false about Stanley’s Boys or who to believe. Marsh, for his part, has maintained his innocence. What is undeniable is that Amarillo has experienced a broad cultural transformation for which Marsh is largely responsible. The home of the Cadillac Ranch and theAmarillo Ramp now has dozens of art studios and galleries, including one sleek white-walled affair that makes you wonder if this town isn’t the next Marfa. Marsh’s influence may have waned somewhat, but even today, along the streets of Amarillo, his presence is everywhere: the tall shambolic man in purple chaps, walking into a courtroom with a bucket of cow manure.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.