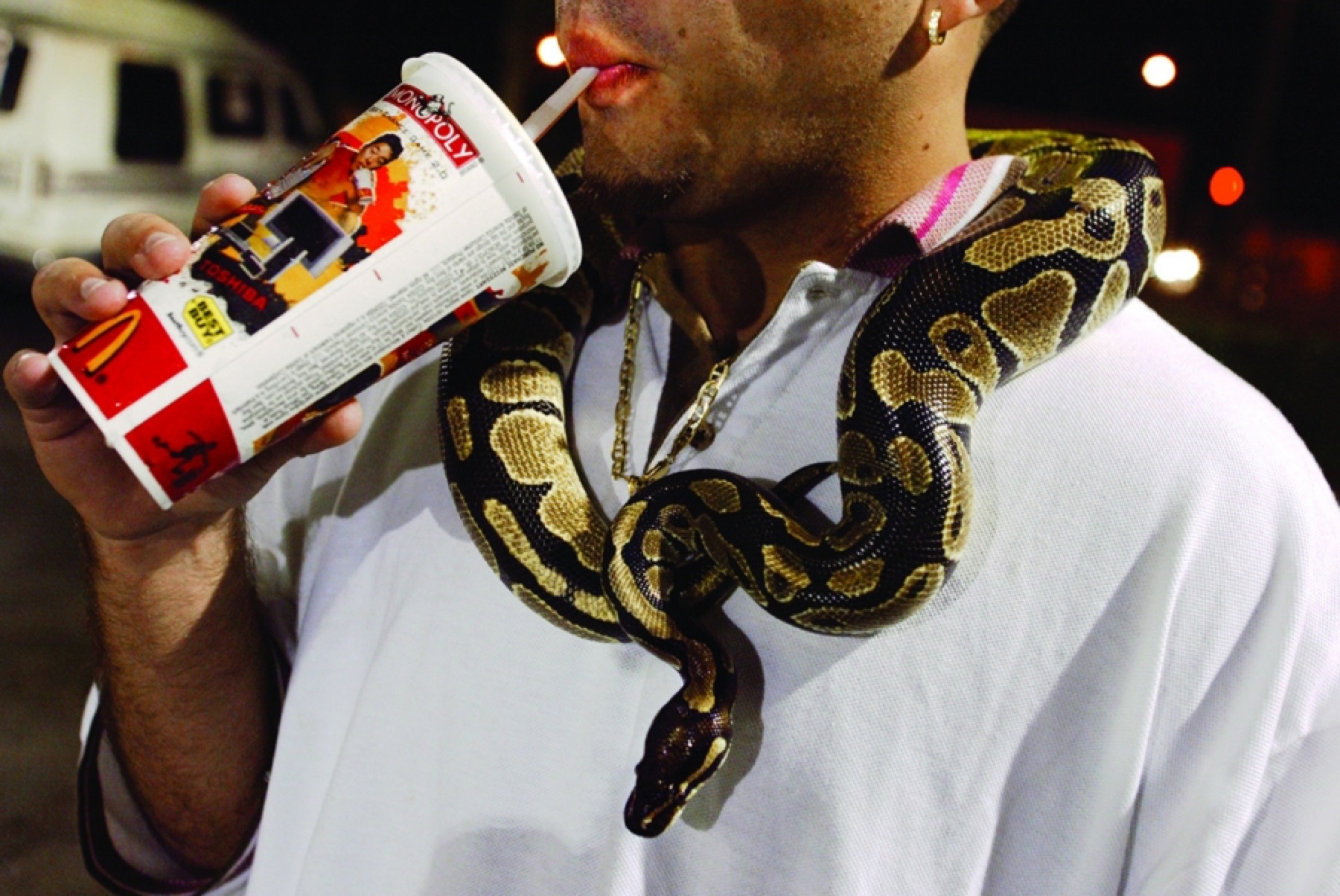

"Serpent, West Palm Beach, Florida" (2004) by Susana Raab

Fifty Shades of Greyhound

By Harrison Scott Key

On Friday, May 12, 1995, I stepped onto a bus in Jackson, Mississippi, bound for West Yellowstone, Montana. The journey would take four days, with no stops for anything but gas and cigarettes and the occasional disemboweling of one passenger by another. When I said goodbye, my father, who only embraces things when he is trying to kill them, hugged me. It was his way of saying: Your mother thinks you might die.

When I tell this story, sometimes people ask why, given my general state of mental health and fiscal stability, I would choose to ride to the other side of the North American landmass in the world’s fastest portable toilet, passing through a gauntlet of unholy downtowns where I would likely be accosted by psychotic barnacles who desired to rape and eat my carcass behind an America’s Best Value Inn.

The answer is simple: I wanted to see a mountain, a topological feature I had often read about in books. In Rankin County, Mississippi, we had many books, but no mountains. When it was all over, when I peeled myself from the backseat of the bus two months and 4,200 miles later, carrying a box of Hostess Chocodiles that had constituted my only foodstuffs in three days, having lost all of my underwear and much of my mind, I found my mother waiting for me at the bottom of the steps, weeping.

“Promise you won’t do this again,” she said.

I promised.

And eighteen years later, I broke that promise. Because I wanted to see another mountain.

One of the most surprising qualities of the Greyhound station in Savannah is its lack of parking. How did they expect people to get to the station? Given the clientele I noted in the predawn darkness, the answer appeared to be: on crutches.

I was excited to meet them. Bus People are nothing like Airplane People, who are boring and have “luggage” and enjoy “skiing.” Bus People, on the other hand, enjoy “talking about grenades” and “screaming.” In ’95, I met a woman in Wichita Falls who said she was the first person to taste Dr Pepper, when she was five, which would have made her 115 years old, which made her a liar. In Billings, I met a Crow Indian who wore a stovepipe hat and either wanted to hug or stab me, it was unclear. Would such people be on my bus in Savannah? And was it wrong to want them to be?

These were my thoughts as I looked at the other passengers and noted a woman wearing a bologna sandwich on her head. Was there really a bologna sandwich on her head? Yes, unmistakably. Also, she wore a blue Snuggie.

On the wall, a poster: the bus of the future has arrived.

The Future-Bus was depicted in new colors: silver, blue, and black. The message was clear. This is not your grandmother’s Greyhound, which was silver, blue, and red. I was eager to experience this futuristic bus. Things were looking up. What I was experiencing, of course, was Greyhound Stage One: Hope.

Early in one’s journey, one begins to appreciate the candor of the Greyhound operation. Nobody here is trying to act like this is fun. And one begins to realize: that’s okay. For example, nobody “invites” people to board. Rather, a designated staff member stands on a chair and shouts the names of nearby villages, whether or not they have any relation to actual destinations of the bus. If a P.A. system is available, staff members will use it both to inform and disorient passengers, eliminating every few words.

“All passengers going to KSHHHH at this time please KSHHHH, otherwise, it’s very likely that KSHHHH until you bleed to death.”

The terminal signage is refreshingly honest, too, eschewing the sophistry of advertising for plain American. PHONE, read one sign, hanging over a payphone. Was this for the youth, who perhaps did not understand? DO YOU WANT TO GO HOME? read another sign, which seemed more of a threat. In the Atlanta terminal, a poster: PAY WITH CASH. For what, it didn’t say. Underneath was a picture of twenty dollars and a hand. Was someone buying a human hand? The human hand looked pretty clean and healthy. Good deal for a hand!

Even the overheard conversations have the ring of unvarnished truth, as in this exchange between two young women:

“Man, if I die at a Greyhound station, nobody will know.”

“I will know.”

“Yeah, but then you be dead, too.”

“Yeah, I guess so.”

One thing was for sure, this Bus of the Future was equipped with Truth.

The transition was quick to Greyhound Stage Two: Concern. “Charleston! Going to Charleston! Load it up! Argh!” Was he our driver? Possibly also a pirate? We hustled out through a tarpaulin into the dark, and boarded before sunrise. Our driver spoke in a velvety Barry White baritone that hushed us like babies, announcing stops in Charleston, Georgetown, Myrtle Beach, Florence, Camden, Fort Jackson, Columbia, Cartagena, Tierra del Fuego, Mos Eisley, Mordor, and the Spice Planet of Arrakis.

I woke up again in Charleston, a historic city where I hoped to espy some columned portico gaily festooned for that evening’s cotillion, but was instead no less pleased to see across the street from the terminal a charming mercantile exchange called El Cheapo. My morning coffee beckoned for release, and I visited the onboard restroom. Best to do this when the bus is stopped, I deduced, for reasons that are immediately obvious to anyone who has straddled a bucket of someone else’s feces at high speeds. I entered and beheld a horror. The Bus of the Future, it seemed, was covered in the gastrointestinal ailments of the past. What toilet paper remained appeared to have been ripped from the wall and attacked by a ferret.

One of the great things about Greyhound is that there are many toilets in which one can die. What to call this onboard bathroom? Not a restroom, for it is not restful. Not a water closet, for there is no water. Perhaps asphyxiation nook? Death slot? Concern flowers imperceptibly into Greyhound Stage Three: Fear.

It only seemed fair to wait and investigate the terminal toilet in Myrtle Beach, which was rumored to be clean, or at least anchored to the earth. After refusing a Gideon Bible upon exiting the bus, on account of my having already read it, I stood in line for the restroom. A woman exited, and I entered, locked the door, loosened my garments, and was immediately clad in darkness. The lights went out. Having failed to wear a headlamp and now surrounded by exposed wiring and unidentified pathogens on every unseeable surface, I considered screaming for assistance. I regretted not taking one of the free Bibles, for the comfort it might provide in my final moments.

Having eventually freed myself, I walked outside and stood next to a man who had stepped out of central casting on his way to Thunderdome. His name was Barrel. You know how people named Clark just “look” like a Clark? Well, Barrel just “looked” like a murderer. He had the size and build of a grain silo wrapped in denim and wore at least two pairs of jeans. Also, he carried an aluminum grabber tool. It was his hair, though, that was most worthy of note, for his large sunburned head was home to two quite opposing hairstyles: the front hemisphere shorn to stubble, the rear running wild in thick fields of ripe, silvery wheat, the two halves divided by a perfect prime meridian of barbering, as though he had jumped from the barber’s chair mid-haircut, having been alerted of more denim in the area. He looked like a sort of demented Hell’s Angel Hobo Viking. “What do you call that kind of haircut?” is what I would have asked, had I wanted to die.

Barrel was engaged in conversation with a smaller man who rested an injured leg on a basket of laundry. Their conversation concerned the nature of his wound and the universe.

“You got a rod there in your leg?” asked Barrel.

“Yeah,” said Leg Boy.

“Does it take the place of your shinbone?”

“Sure.”

“It’ll be hellfire if there ever was.”

“In Ohio at least.”

“Might even get the old burning bush if you lucky.”

“I’ll tell you what it was—” said Leg Boy, preparing to drop on us some Leg Wisdom. But what sort of dramatic zeniths such dialogue could reach, I shall never know, because Barrel stopped his interlocutor to ask:

“Say, you ever listen to Bob Seger?”

On a bus, people speak as if they shared long histories. And I suppose the bus becomes its own kind of long history. Eighteen years before, I met a veteran from the first Gulf War who, standing outside the Cheyenne station, surveyed the vast plains before us and announced to me, “All women want to kill a man.” I had met him ten, maybe fifteen minutes before. At the time, I assumed he was mentally disturbed. But having now been married ten years to a woman in whose eyes I have seen murder, I am not so sure.

One doesn’t hear such truths on Delta. There’s no time for it. And that’s the one thing Greyhound has plenty of.

There comes a time in every Greyhound journey when the switch is flipped. Gone is the sanguine, tolerant liberal arts major who believes in the beauty of human frailty and the quiet dignity of poverty, replaced by a famished hobgoblin with scoliosis. The transformation is largely a result of the seats. They are not bad seats. They even recline, which is nice, although it’s not really reclining, but more of an opportunity to continue to be uncomfortable while shattering the previously injured shinbones of those in one’s immediate rear.

The problem with the seats is what happens when there’s an empty one next to you. On an airplane, an empty seat is a small miracle, a sacred place to set one’s book. On a bus, though, the empty seat invites lurid napping positions that resemble the attitudes of those who’ve been buried in lava and discovered many years later.

On an airplane, seats are reserved. When a flier approaches, especially when he is ovular in shape, one quietly prays that the Lord has predestined him to sit somewhere else, preferably near a small screaming child, whom the large person may by chance desire to eat. But if he sits next to you, you understand: it is not his fault. Not so on a bus, where seats are unreserved, where one’s only recourse to keeping a seat open, short of detaching a limb and placing it there, is to appear insane.

There in Myrtle Beach, twenty of us had been invited to reboard while newer travelers pressed toward the door to menace the cabin. As they began to board, I looked around. Fifty seats. Twenty of us, sitting alone. That’s forty seats taken, leaving ten. Which is really five. The first five new passengers emerged, claimed these empty pairs of seats, and the cabin grew tense. Every new passenger shot up into the bus and began to search for a victim, someone with whom to mingle bodies and odors. Our open seats were our most valuable currency, and they were about to be taken from us. My only choice, I knew, was to look crazy.

But how does one look crazy? My wife had often told me to not look at her “all crazy like that.” “Like what?” I would say. “With the dead eyes,” she would say.

I made the dead eyes. Also, I set my baseball cap high on my head, so I looked like a farmer with dead eyes. But the eyeglasses, those professorial spectacles! They would undo me, make me look dependable and cogent. And so I turned them upside down, which made me look undependable and German. Then I slouched a little and bared my teeth, as though I had been dead for many days. A small, grandmotherly woman of what looked like Oceanic provenance shuffled toward me, surveying me like a large fruit she wished to purchase.

She moved on.

The bus exhaled, raised up, lurched forward. I held my pose of the German farmer corpse for a good ten minutes, until everyone was settled. A girl in a Haverford sweatshirt eyeballed me over a seat. What was someone like her doing on this bus? Was she taking notes? What was she, some kind of journalism major? Stop taking notes about me! I am not an animal!

Greyhound Stage Four: I Am An Animal.

Had it really taken ten hours to get to the capital of South Carolina? I hadn’t eaten in a full day and hobbled off the bus in search of meats. In the terminal parking lot, I noted with delight an unfinished wiener that had been dropped onto the asphalt. Of course I wouldn’t eat it. Of course. But then, there it was. Shouldn’t I pick it up? To throw it away, or put it in my shoe?

My previous life as a homeowner and member of many benevolent societies had grown dim. Who was that man? He smelled of luxurious soaps and lotions. What relation was he to this old, stooped pilgrim, whose coy limbic system now believed it was operating inside a homeless man? I walked away from the terminal, over a hill, where I noted many fine eating establishments. Were they real? Dare I risk missing my connection for the procuring of their meats? Onward I walked, pausing at a gas station to purchase cigarettes, for I no longer feared death.

I found myself on the median, where my weariness overtook me and I sat down to smoke, which drew the attention of passing officers of law enforcement, who sent glad tidings to me through their loudspeakers. In time, I made my way onto the porch of a taco establishment that sold cans of beer, of which I consumed many. My jangled nerves calmed, and I noted the time was 5:25 p.m. Casually, I also noted the time of departure on my ticket was 5:30 p.m.

I ran.

Up the hill.

Past a craps game.

Past a man who wanted a quarter.

Running, sweating, backpack heaving to and fro, I ran. I ran so hard my crack was showing. When I finally made it to the queue, a cigarette behind my ear, gray with my athletic ministrations, beer in hand, tomatillo on my pants, vaporous abominations about my person, I realized my transformation was complete.

“What up?” a passenger said.

“Chilling,” I said, panting.

“I get one dem smokes, homes?”

We smoked, there in the line, me and my homeskillet.

Four hours later, and with a crick in my neck that rendered me unusually susceptible to attack from my immediate right, I woke up on a mountain. It had taken us fourteen hours to travel three hundred miles, which is less than half the average running speed of the dog with the same name as the bus.

Had I really made it? Yes. Was I a changed man? Perhaps. What would my new life be like, with limited lumbosacral function? Interesting. But I no longer cared. I had achieved Greyhound Apotheosis, the strange, unbidden nirvana that comes after the hope and anxiety and fear and dementia blur like roadside trees. A certain peace overcomes one.

A funny thing happens when you tell people you’re about to ride a Greyhound bus: They give you a look, like you asked them to smell a sock you found in the garbage.

“On purpose?” they ask.

“Yes,” you say.

“But why?” And their voices will drop and they lean in. “Is everything okay?” What they are saying, of course, is that People Who Are Okay do not ride buses, unless those buses are going to Disney World. These people cannot handle the Truth of the Bus. And what do we learn from this Truth? Many things. How to carry one’s clothes in an ice chest, or a bologna sandwich on the head. What a human hand costs, what a phone is. And what women want. And also what Bob Seger’s fans want. And that perhaps more of us are one bad month from needing to ride Greyhound than we’d like to admit, and that some of us are already there.

These are not easy truths to learn. But there’s another kind of reaction you get when you’re about to ride a bus. What you get is a look. A look that remembers. “I did it once, when I was nineteen,” they say, dreamily, as though speaking of an enchanted evening many moons ago filled with love and peyote and the cries of distant coyotes. And they will tell you where they went—Memphis to Cincinnati, Denver to Mobile, Jackson to Yellowstone—and they will not speak harshly of the seats, the stations, the toilets. They will remember only the people and the America it showed them and the wild and reckless reasons that drove them to it: to see a girl, or a headstone, or a mountain. And they will recall it fondly, as I do now.

And they will not want to do it again. But they will want to be able to do it again. It is a dream they have, you can see. To just leave. Deep urges they do not understand will drive them to go. One day, again, soon. And there is a bus waiting to take them there.

A Bus of the Future.

They say it has Wi-Fi and toilet paper.

Enjoy this story? Subscribe to the Oxford American.